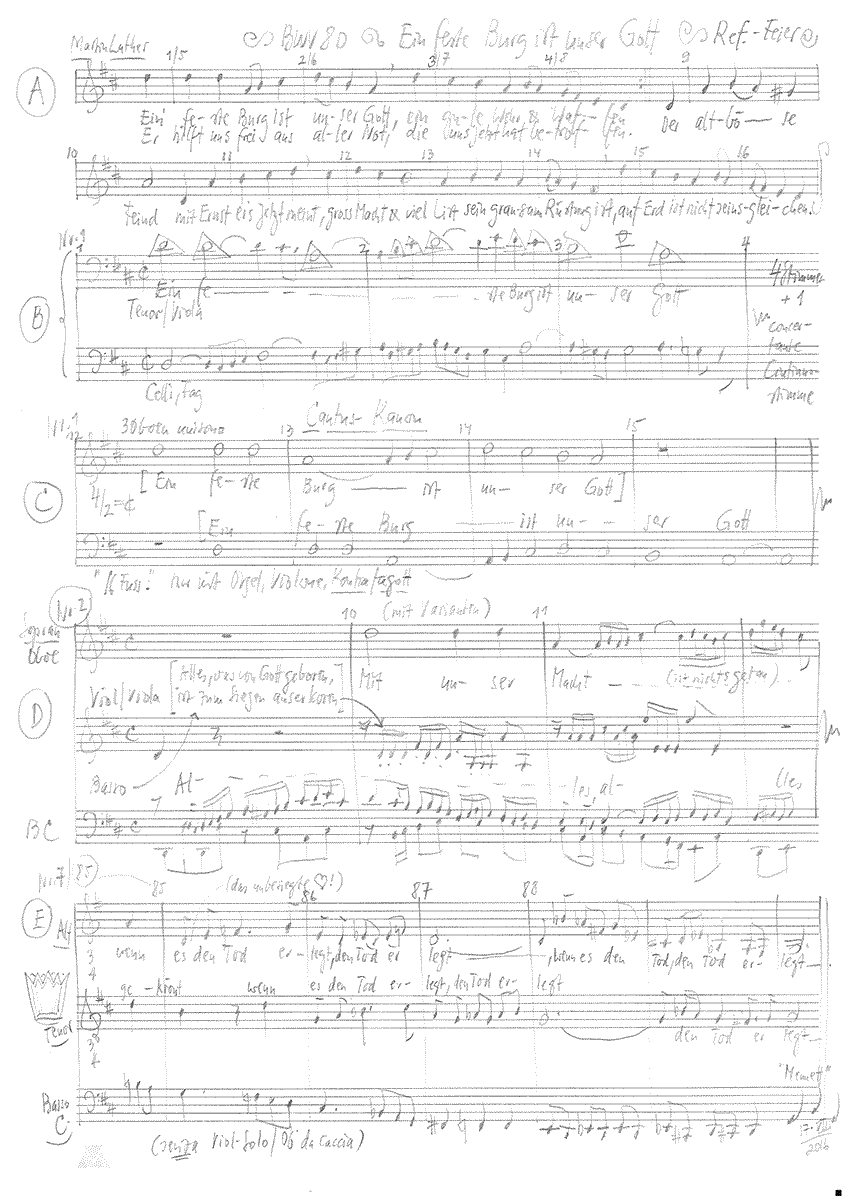

Ein feste Burg ist unser Gott

BWV 080 // For Reformation Sunday

(A mighty fortress is our God) for soprano, alto, tenor and bass, vocal ensemble, oboe I–III, oboe d’amore I–II, oboe da caccia, taille, trumpet, timpani, organ, strings and basso continuo

Bach’s cantata BWV 80, “A mighty fortress is our God”, is set to Luther’s spirited hymn from 1529 that first entered the Protestant canon after the reformer’s death. The cantata is based on a Weimar composition written in 1715 for Oculi (the Third Sunday in Lent), whose opening bass solo “All that which of God is fathered” quotes the chorale melody “A mighty fortress” as an additional commentary layer. It was perhaps this loose relationship to the chorale that led Bach to reuse the Weimar composition in Leipzig for Reformation Sunday; initially, he added a distinguished chorale setting at the beginning of the work, which he replaced in the 1730s with an extended chorale motet. Bach’s son, Wilhelm Friedemann, later borrowed the first and fifth tutti movements for his own church music in Halle, adding Latin libretti and a choir of trumpets and timpani – instruments that are occasionally used in his father’s version to this day. Despite the compositional mastery of the cantata, a distinct tension is evident between the compositional layers of the Reformation and Oculi settings. While the heroised image of Bach in the 19th century led to performances emphasising the large choral movements, today the intimate nature of the solo Weimar movements does not go unappreciated.

Would you like to enjoy our videos ad-free? Subscribe to YouTube Premium now...

Workshop

Reflective lecture

Bonus material

Choir

Soprano

Lia Andres, Felicitas Erb, Olivia Fündeling, Susanne Seitter, Noëmi Sohn Nad, Noëmi Tran Rediger

Alto

Jan Börner, Antonia Frey, Francisca Näf, Alexandra Rawohl, Damaris Rickhaus

Tenor

Marcel Fässler, Clemens Flämig, Raphael Höhn, Nicolas Savoy

Bass

Fabrice Hayoz, Matthias Lutze, Jonathan Sells, Philippe Rayot, Tobias Wicky

Orchestra

Conductor

Rudolf Lutz

Violin

Plamena Nikitassova, Lenka Torgersen, Christine Baumann, Claire Foltzer, Petra Melicharek, Dorothee Mühleisen, Christoph Rudolf, Ildikó Sajgó

Viola

Martina Bischof, Sarah Krone, Sonoko Asabuki

Violoncello

Maya Amrein, Hristo Kouzmanov

Violone

Markus Bernhard

Oboe

Philipp Wagner, Dominik Melicharek, Ann Cathrin Collin

Oboe d’amore

Philipp Wagner, Dominik Melicharek

Oboe da caccia

Philipp Wagner

Taille

Ann Cathrin Collin

Tromba da tirarsi

Patrick Henrichs, Peter Hasel, Pavel Janecek

Timpani

Martin Homann

Bassoon

Susann Landert

Contrabassoon

Alexander Golde

Organ

Nicola Cumer

Harpsichord

Jörg Andreas Bötticher

Musical director & conductor

Rudolf Lutz

Workshop

Participants

Anselm Hartinger, Karl Graf, Rudolf Lutz

Reflective lecture

Speaker

Johannes Anderegg

Recording & editing

Recording date

19.08.2016

Recording location

Teufen AR (Schweiz) // Evangelische Kirche

Sound engineer

Stefan Ritzenthaler

Director

Meinrad Keel

Production manager

Johannes Widmer

Production

GALLUS MEDIA AG, Switzerland

Producer

J.S. Bach Foundation of St. Gallen, Switzerland

Librettist

Text No. 1, 2, 5, 8

Martin Luther

Text No. 2, 3, 4, 6, 7

Salomo Franck, 1715

First performance

Unknown,

probably after 1729/31

In-depth analysis

The introductory chorus features no prelude, opening directly as a fugal motet with doubled instruments. By additionally integrating the cantus firmus in a two-part canon, Bach raises the archaic motet, a form well suited to the venerable occasion, to a setting of exceptional grandeur. To this end, the continuo group is divided into an accompanying part for violoncello and harpsichord, and a melodic bass part for organ and violone that underscores the thee oboes presenting the same melody two octaves higher. The chorale bass voice, generally played on the organ pedals or on a trombone, is played in our recording on a 16-foot contrabassoon, the instrument Bach used in version IV (1749) of his St John Passion.

In the ensuing duet, the urgent, unison string lines set over a rumbling continuo perfectly enhance the spur-rattling text and the victorious coloturas. It is music of a truly Lutheran pen, with a setting that signifies the act of baptism as a symbol of the New Covenant and Christ’s matyrdom as the source of solace. The combination of a ritornello aria with a chorale setting posed Bach with a considerable challenge, particularly in the cantabile middle section. While the ever-present energy of the strings enforces consistency, the reuse of the chorale as an additional, figured voice – both textually and instrumentally – lends the first two cantata movements the character of a partita through which Bach seemingly reconciles his duties as court organist and concertmaster.

The bass recitative takes up the notion of the blood sacrifice of Christ, but interprets the eschatological struggle as a perpetual fight against the world and Satan. The closing arioso section, which speaks of the unity of Christ’s soul and the human heart, is so replete with sharps that it appears Bach had well understood the Lutheran books so prominent in his theological library: despite the promise of mercy, it is audibly difficult for humans to make their lives subservient to the healing act of penitence. Thus, Luther’s theology of the Cross is revealed as a severe message, whose painful energy is released in a continuo coda of almost Schumann-like character.

The soprano aria “Come in my heart’s abode”, among the best of Bach’s Weimar-style arias, presents a tender hymn of love in which anxious hope is balanced by awareness of one’s own unworthiness. After a defiant middle section, the movement closes with a reprise of even greater heights and poignancy.

Set in D major, the battle music of chorus number five “And were the world with devils filled” marks an abrupt shift in tone. The unison setting of all vocal parts – highly rare in Bach’s oeuvre – evokes a sense of denominational unity, while the lively “military gigue”, cited here in the medium of art music, suggests the chorale singing of the faithful thousands gathered in the main churches of Leipzig. An appealing mix of congregational hymn and Brandenberg concerto, this setting makes apparent the potential unleashed by the Leipzig council in appointing the talented Kapellmeister and organist to the position of Thomascantor. The moving tenor recitative, a sharp reminder that faith is the true path to victory of the spirit, leads the listener back from the communal level to the individual soul. Then, in the sermon-like conclusion “Thy Saviour is thy shield”, the continuo and soloist unite in a blissful cantillation.

The following duet is introspective in character. The Leipzig version opens with solo parts for oboe da caccia (not used in Weimar) and violin, before the alto and tenor voices enter in tender harmonies. Although the opening text criticises the hollow recital of prayer as compared with the true faith of the heart, Bach does not exploit this theme in dramatically contrasting tones. Rather, the composer is “at cross purposes” with the libretto, giving both the weak and strong of faith equal opportunity to find loving solace in the blissful rapture of the music. These evocative tones then engender a triumphant middle section that quotes the quarrelsome music of the second movement; in the calm conclusion, however, the ultimate goal of crowning life with a Christian death is rendered clearly audible.

The closing chorale responds with words of unified strength. Nonetheless, the fatalistic lines “Our body let them take, Wealth, rank, child and wife, Let them all be lost, And still they cannot win;” remain painful to endure. Indeed, one cannot help but wonder if the aging Luther, in his intense bereavement for his beloved daughter Magdalena, had cause to regret such high-flown rhetoric.

Libretto

1. Chor

Ein feste Burg ist unser Gott,

ein gute Wehr und Waffen;

er hilft uns frei aus aller Not,

die uns itzt hat betroffen.

Der alte böse Feind,

mit Ernst ers itzt meint,

groß Macht und viel List

sein grausam Rüstung ist,

auf Erd ist nicht seinsgleichen.

2. Arie (Bass) und Choral (Sopran)

Alles, was von Gott geboren,

ist zum Siegen auserkoren;

Mit unser Macht ist nichts getan,

wir sind gar bald verloren.

Es streit’ vor uns der rechte Mann,

den Gott selbst hat erkoren.

Wer bei Christi Blutpanier

in der Taufe Treu geschworen,

siegt im Geiste für und für.

Fragst du, wer er ist?

Er heißt Jesus Christ,

der Herre Zebaoth,

und ist kein andrer Gott,

das Feld muß er behalten.

Alles, was von Gott geboren,

ist zum Siegen auserkoren.

3. Rezitativ (Bass)

Erwäge doch,

Kind Gottes, die so große Liebe,

da Jesus sich

mit seinem Blute dir verschriebe,

womit er dich

zum Kriege wider Satans Heer

und wider Welt und Sünde

geworben hat!

Gib nicht in deiner Seele

dem Satan und den Lastern statt!

Laß nicht dein Herz,

den Himmel Gottes auf der Erden,

zur Wüste werden!

Bereue deine Schuld mit Schmerz,

daß Christi Geist mit dir sich fest verbinde!

4. Arie (Sopran)

Komm in mein Herzenshaus,

Herr Jesu, mein Verlangen!

Treib Welt und Satan aus,

und laß dein Bild in mir erneuert prangen!

Weg, schnöder Sündengraus!

5. Choral

Und wenn die Welt voll Teufel wär

und wollten uns verschlingen,

so fürchten wir uns nicht so sehr,

es soll uns doch gelingen.

Der Fürst dieser Welt,

wie saur er sich stellt,

tut er uns doch nicht,

das macht, er ist gericht’,

ein Wörtlein kann ihn fällen.

6. Rezitativ (Tenor)

So stehe dann

bei Christi blutgefärbten Fahne,

o Seele, fest

und glaube, daß dein Haupt dich nicht verläßt,

ja, daß sein Sieg

auch dir den Weg zu deiner Krone bahne!

Tritt freudig an den Krieg!

Wirst du nur Gottes Wort

so hören als bewahren,

so wird der Feind gezwungen auszufahren,

dein Heiland bleibt dein Hort.

7. Arie (Duett Alt, Tenor)

Wie selig sind doch die, die Gott im Munde tragen,

doch selger ist das Herz, das ihn im Glauben trägt!

Es bleibet unbesiegt und kann die Feinde schlagen

und wird zuletzt gekrönt, wenn es den Tod erlegt.

8. Choral

Das Wort sie sollen lassen stahn

und kein Dank dazu haben.

Er ist bei uns wohl auf dem Plan

mit seinem Geist und Gaben.

Nehmen sie uns den Leib,

Gut, Ehr, Kind und Weib,

laß fahren dahin,

sie habens kein Gewinn;

Das Reich muß uns doch bleiben.

Johannes Anderegg

“Eine feste Burg” – Thoughts on the texts of the cantata BWV 80

Martin Luther: steadfast

Luther’s time was a time of war. Luther’s religiosity is based on the experience of battle and threat, and it is from the experience of war and the need for security and safety that the image of God in Luther’s song takes on its special, concrete spatial character: a firm castle. God as a securing, as a sheltering castle – the image comes from the Psalms, from Psalms that themselves refer to the experience of war and hardship. Ps 9 – which can also be read as a psalm of thanksgiving, for the “enemy is destroyed, forever in ruins” (v. 7) – already captures trust in God in the image of God as a “fortress in time of trouble” (vv. 9, 10), and the singer of Ps 46 knows that God “puts a stop to wars” and assures: “The Lord of hosts is with us, / a fortress is the God of Jacob to us.” (V. 8, 10, 12)

Luther’s hymn text (stanzas 1, 5, 8 and parts of stanza 2 of the cantata) reminds us that the threats Luther and his companions faced were quite real and varied. Warlike conflicts threatened “life, property, honour, child and wife” in Germany. A constant threat, partly as a result of the wars, are the rampant diseases, the epidemics, especially the plague. And Luther and those close to him are threatened by the church loyal to the Pope, which rejects the new teachings and wants to maintain its power, and which allies itself with secular rulers for this purpose.

In his song, Luther understands the threats posed by the enemies and by the enemy – in this respect he is still influenced by medieval thinking – as manifestations of the one old evil, the devil. As the epitome of all evil, Satan is the “prince of this world” – a designation Luther takes from the Gospel of John (John 16:11; 12:31) and which is similarly found in Paul’s letter to the Ephesians (Eph 2:2; 6:11); it testifies not only to the power of evil but also to the dire state of the world. That the “prince of this world” should and can be stopped from the castle – this is what Luther’s song is about.

History teaches us – and Luther knows from his own experience – what can happen to castles. Not only today, but already in his time, the ruins of razed, smoked-out castles rise up as terrible memorials all over the country. That is why Luther is more precise in his hymn: God is a “firm castle” to him, an impregnable “fortress”, in today’s language: a fortress.

The function of a fortress was clearly defined then as it still is today: it is not a place of attack but of defence, it is a place of resistance and at the same time a place of protection, it is, according to Luther, a “weir”, it repels attacks. As a fortress, it defies the onrushing enemy with “great power and much cunning”. In his song, Luther sees himself and those with him not as attackers, but as those who are threatened; and he sees himself as a defender, namely as an energetic defender of Christianity – his Christianity – and that means for him: as a defender of Holy Scripture, from which alone Christianity is to be understood and realised – a principle which the Papal Church fights just as energetically. That’s why he counters the enemies with: “Let the word stand”.

Luther’s song may be understood as a battle song, but as such it does not call for aggression, but demonstrates the unity and steadfastness of the faithful in upholding the faith. The firmness of its defenders is part of the firmness of the castle. The model of such steadfastness is the attitude demanded by Stoic philosophy. Luther also speaks of steadfastness in faith in other writings, for example in his treatise On the Freedom of the Christian; it has become proverbial in the saying attributed to Luther, “Here I stand, I cannot do otherwise”, and in many later assurances of faith it proves to be a core statement, for example in an impressive verse by the Protestant mystic Catharina Regina von Greiffenberg (1633-1694): “I stand rock-solid in my high hope”.1

Anyone who has ever been in a fortress knows it: It is cramped in a fortress; there is hardly any room for movement, there is no room for manoeuvre. The tightly drawn walls offer protection precisely because they confine and exclude with harshness. Such a hardness of demarcation – already expressed in the exclusionary formulation “our God” – is fundamental for Luther’s firmness in faith and for his theological system. Exemplary illuminates the uncompromising inclusion and exclusion from the four Latin and buzzword-like formulated (and therefore also often misunderstood) statements of faith, which also determine the character of the choral text: For Luther, the centre is Jesus Christ (solus Christus) alone: “the Lord of hosts “2. The basis for this is “the Word” alone, the Holy Scriptures (sola scriptura), whose individual books, however, Luther weights quite differently. Salvation cannot be acquired, but only expected from God’s grace (sola gratia), and unconditional faith (sola fide), which underpins the entire hymn text, trusts in it.

Luther’s impressive assurance of faith, which is expressed particularly succinctly in the last verse – “The kingdom must remain with us after all” – admittedly refers exclusively to a victory in the spiritual realm. The “kingdom” that remains for believers in spite of all worldly horrors and losses is not of this world. From today’s perspective, this exclusivity in the orientation towards the spiritual is not easy to comprehend: It allows for individual social behaviour, but it excludes socio-political and institutional commitment to the weak and the oppressed. Thus, to cite the most famous example in this context, Luther refuses to support the peasants whose revolt against the oppressors was undoubtedly triggered by his Reformation teachings. And since his concept of the freedom of a Christian man refers to the “kingdom of Christ” but not to the “kingdom of the world”, he finally even demands that the authorities punish the leaders in the name of Christianity. He is equally harsh against the Anabaptists, whose movement could not have arisen without the new teaching. In many respects, and especially with his translation of the Bible into German, Luther opened doors to the modern age; but his struggle to enforce his doctrine, his theological system, his unconditional demand for an unambiguous confession of faith and the exclusion of those whom he did not want to recognise as Christians are reminiscent of the medieval-like methods of that church from which he had renounced in the name of Christianity. After Luther, it will take many hundreds of years before the churches are ready to take seriously the admonition formulated in the First Letter to the Corinthians – “if I have all faith to move mountains, but have not love, I am nothing “3 – and to recognise commitment to the weak and oppressed as their Christian duty.

Salomo Franck: admonishing

For his cantata Ein feste Burg ist unser Gott (A Mighty Fortress is Our God), Bach took the musical theme and the chorale text from Luther, but with extensions that came from the pen of Salomo Franck (1659-1725). Salomo Franck, librarian at the ducal library in Weimar, occasional poet and author of sacred poems, wrote numerous cantata texts for Johann Sebastian Bach, who also worked at the Weimar court from 1708 to 1717. He is not to be confused with August Hermann Franck (1663-1727), who was active in Halle, the Pietist centre, during the same decades and who gained fame and recognition for his many social commitments, especially in the field of education.

Salomo Franck had actually conceived his text for a cantata for the third Sunday of Passiontide – with loose references to the corresponding pericopes4 – and concluded it with verses from Luther’s chorale. Aspects of Luther’s text echo in Franck’s verses, but he modifies them, and some he flattens, precisely by sharpening them. Unlike Luther, he speaks explicitly and repeatedly of “war”, of “war against Satan’s army and against the world”, but this army of Satan does not mean external enemies, rather it is to be driven out of the heart. Luther’s certainty that the “kingdom” remains for believers is transformed by Franck into talk of “victory” and “victories “5 , not without making it clear that the victory is not in the world, but “in the spirit”. With the twelve-fold repetition of the pronoun “us” or “our” in Luther’s hymn text, the singing parishioners assure themselves of their community in faith; Franck individualises and dramatises the emergence of this community and thus gambles away the community-building power of Luther’s language: “Victory” will come to those who “by Christ’s blood panier / in baptism faithfully swore”. The metaphor is irritating: on the one hand, because Jesus generally forbids swearing (by heaven and earth) in the Sermon on the Mount (Mt 5, 34), on the other hand, because Franck stylises Christ’s Passion into a sign of war – a “blood panier”, later a “blood-stained flag” – and finally, because a baptised person can hardly swear, unless it is one of the Anabaptists, whom Luther is known to have fought pitilessly.

Franck makes a different shift in emphasis from Luther’s text by alluding to Eph 5:1-8, moralising and also here individualising the call to fight against sin and vice and to repent: “Do not give way in your soul / to Satan and vice!” If one adheres to Franck’s verses – “Repent of your sins […] that Christ’s spirit may be firmly united with you!” -closeness to Christ is not to be gained through faith, as with Luther, but through repentance.

Salomo Franck certainly did not intend to question Luther’s theology, but the religiosity that is expressed in his verses has a different character than Luther’s religiosity. Franck’s language is fed from different sources, so it seems stylistically inconsistent and – compared to Luther’s powerful figurative language – rather awkward. From the metaphor of war in the second movement of the cantata, Franck arrives abruptly at the terms “love”, “soul” and “heart”, which the language-shaping movement of Pietism made into leading concepts; with its shift of religiosity to subjective inwardness, this is one of the most important reform movements within Protestantism. The orientation towards the terms “love”, “soul” and “heart”, however, manifests not only a changed religiosity, a more emotional faith in Christ, but also a general cultural change, whose first secular phase has gone down in cultural history as the time of “Empfindsamkeit”.

The conceptual difference between Luther’s and Franck’s texts becomes even more striking in the fourth part of the cantata, for here Franck simply turns Luther’s fundamental image of faith upside down: Instead of God as a strong fortress, there is now talk of the “house of the heart” in the language of inwardness and of the “longing” for Jesus, who may move into the “house of the heart” and drive “the world and Satan” out of it. Franck’s fixation on the problem of sinfulness almost obscures the fact that he takes up the metaphorics of the mystical tradition in these verses. At the beginning of the 17th century, for example, the Catholic mystic Friedrich Spee addressed the soul’s “longing” for its beloved Jesus in many of his poems that can be read as love poems proper.6 The basis for the depiction of the soul’s relationship to Jesus as a longing for love is the language of the Song of Songs, whose Christian interpretations have legitimised the eroticisation of religious metaphor.7

Barthold Brockes: grateful

The period in which Franck writes sacred texts for Bach, the so-called early Enlightenment period, is, unlike the time of Luther, a comparatively peaceful time. The right to individually pursue worldly or religious happiness is increasingly recognised, and a general subjectification of one’s outlook on life gains in importance. Interest in dogmatic disputes wanes; even within Protestantism, positions that deviate from Lutheran orthodoxy can be articulated reasonably freely, if not from the pulpit, then at least in religious poetry. While Franck deviates from Luther, but in his verses neither linguistically nor theologically goes beyond the framework of what was conventional in his time, others are now breaking new ground both linguistically and theologically. For example, the religious poems of a likewise Protestant poet who is hardly known today but was unusually successful at the time read like counter-texts to the verses of Luther and Franck: in the poems of Barthold Hinrich Brockes’ (1680-1747), which he published under the programmatic title Irdisches Vergnügen in Gott (Earthly Pleasure in God), there is no mention of battle, war or threat, nor of sin or Satan. His great theme is the admiration of nature and in general the glory and harmony of creation, in which he sees the omnipresence of God manifested. As a creature, man is also part of the admirable creation: Brockes therefore does not portray man as sinful or in need of salvation. His poems – counter-images to Luther’s contempt for corporeality – rather remind people of the happiness of their existence, for which they owe thanks and honour to the Creator. It is this language of grateful worldliness that Bach also uses when he comments on the basic features of his music: The basso continuo, for example, he explains, produces a “melodious harmony […] for the glory of God and permissible delight of the mind”.8

Johann Sebastian Bach

In the history of music, it is often said that Bach took the respective text very seriously in his settings, depicting it musically, illustrating it or commenting on it. Examples of this can also be found in the cantata Ein feste Burg ist unser Gott: One might perceive the orchestra’s opening as a musical expression of certainty of victory and associate the tempo or the vehemence of the strings in the second and fifth movements with the theme of battle; and the soprano aria, it is said, emphasises the “subjective aspect of Jesus’ victory over Satan “9. There is no doubt that Bach’s cantata plays around selected concepts or themes, which thereby set the tone. But the divergence of the textual parts and the diversity of religiosity manifested in them do not worry the composer; as is well known, one of the Protestant composer’s greatest compositions is a Catholic mass. Bach’s music, like music in general, is not a conceptual art; it is much more than an illustration of linguistic images, and it asserts its own existence and being above or beyond the text. And unlike the texts it plays around, it does not demand a confession.

Certainly, like the religious texts that Bach sets to music in the cantata, his compositions are based on a system; it becomes audible in the polyphony, in the basso continuo, in the fugue. But his compositions thrive on the fact that this system not only allows for an immense variety of playing, but also demands it. The cantata Ein feste Burg ist unser Gott makes this no less audible than the Goldberg Variations. In this respect, for all its seriousness, it has a playful quality.

Friedrich Schiller said that a person is only “fully human” when he plays. This play, as Schiller understands it, requires no justification and is subject neither to the “material constraint of the laws of nature” nor to the “spiritual constraint of the laws of morality”. It is based in each case on rules of play, but it is “free from the fetters of every purpose, every duty, every care”.10 Thus Schiller’s concept of “play” is not aimed at sporting activity, but rather at the special status of artistic and musical works and their reception. It seems to me that Bach’s music, that his musical play, in which we participate by making music or listening, comes very close to play as Schiller understands it and gives us a better idea than any theological system of what it means to be “fully human”.

1 Catharina Regina von Greiffenberg: Geistliche Sonette, Lieder und Gedichte, Nuremberg 1662, (reprint Darmstadt 1967), p. 37.

2 In the OT for Yahweh (ruler), in the NT only in Rom 9, 29 and Jas 5, 4.

3 1 Cor 13, 2.

4 Especially to Eph 5, 1-8.

5 The first two verses of the 2nd stanza (the opening verses in Frank’s original cantata text) are a somewhat trivialised version of 1 Jn 5, 4.

6 Friedrich Spee: Trutznachtigall, ed. by Gustave Otto Arlt, Halle 1936. First print: Cologne 1649.

7 Luther also took up the theme ‘Christ as Bridegroom of the Soul’:

Von der Freiheit eines Christenmenschen, in: Luthers Werke in Auswahl, ed. by Otto Clemen, (BoA), Berlin 1967, vol. II, p. 15.

8 Johann Sebastian Bach: Vorschriften und Grundsätze zum vierstimmigen Spielen […],Leipzig 1738.

9 Thus the commentary by Andreas Bomba on the recording of the Bach Ensemble under Helmuth Rilling, CD 92.026.

10 Friedrich Schiller: On the Aesthetic Education of Man in a Series of Letters, in: Ders: Sämtliche Werke, ed. by Gerhard Fricke, Herbert G. Göpfert, Munich 1960, vol. 5, p. 618.

This text has been translated with DeepL (www.deepl.com).