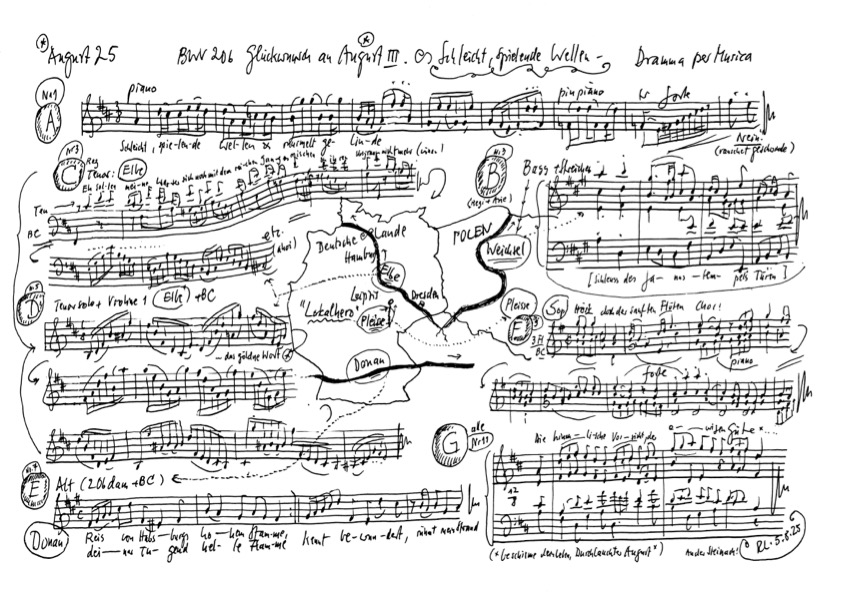

Schleicht, spielende Wellen

BWV 206 // Cantata for the birthday of August III

(Glide, glittering waters) for soprano, alto, tenor and bass, vocal ensemble, trumpet I-III, timpani, transverse flute I-III, oboe I+II, strings and basso continuo

Place of composition in the church year

Pericopes for Sunday

Pericopes are the biblical readings for each Sunday and feast day of the liturgical year, for which J. S. Bach composed cantatas. More information on pericopes. Further information on lectionaries.

Would you like to enjoy our videos ad-free? Subscribe to YouTube Premium now...

Workshop

Reflective lecture

Orchestra

Conductor

Rudolf Lutz

Violin

Éva Borhi, Péter Barczi, Judith von der Goltz, Petra Melicharek, Ildikó Sajgó, Lenka Torgersen

Viola

Martina Bischof, Stella Mahrenholz, Matthias Jäggi

Violoncello

Maya Amrein, Daniel Rosin

Violone

Markus Bernhard

Transverse flute

Tomoko Mukoyama, Sarah van Cornewal, Sara Vicente

Oboe

Clara Hamberger, Katharina Arfken

Bassoon

Susann Landert

Trumpet

Jaroslav Rouček, Karel Mnuk, Pavel Janeček

Timpani

Inez Ellmann

Harpsichord

Thomas Leininger

Musical director & conductor

Rudolf Lutz

Workshop

Participants

Rudolf Lutz, Pfr. Niklaus Peter

Reflective lecture

Speaker

Eva Weber-Guskar

Recording & editing

Recording date

22/08/2025

Recording location

Trogen AR // Protestant Church

Sound engineer

Stefan Ritzenthaler

Producer

Meinrad Keel

Executive producer

Johannes Widmer

Production

GALLUS MEDIA AG, Schweiz

Producer

J. S. Bach-Stiftung, St. Gallen, Schweiz

Librettist

First performance

7 October 1736

Text

Poet unknown

Libretto

Pleisse — Sopran

Donau — Alt

Elbe — Tenor

Weichsel — Bass

1. Chor

Schleicht, spielende Wellen, und murmelt gelinde!

nein, rauschet geschwinde,

dass Ufer und Klippe zum öftern erklingt!

Die Freude, die unsere Fluten erreget,

die jegliche Welle zum Rauschen beweget,

durchreißet die Dämme,

worein sie Verwundrung und Schüchternheit zwingt.

2. Rezitativ — Bass

Weichsel

O glückliche Veränderung!

Mein Fluß, der neulich dem Cocytus gliche,

Weil er von toten Leichen

und ganz zerstückten Körpern langsam schliche,

wird nun nicht dem Alpheus weichen,

der das gesegnete Arkadien benetzte.

Des Rostes mürber Zahn

frißt die verworfnen Waffen an,

die jüngst des Himmels harter Schluß

auf meiner Völker Nacken wetzte.

Wer bringt mir aber dieses Glücke?

August,

der Untertanen Lust,

der Schutzgott seiner Lande,

vor dessen Zepter ich mich bücke,

und dessen Huld vor mich alleine wacht,

bringt dieses Werk zum Stande.

Drum singt ein jeder, der mein Wasser trinkt:

3. Arie — Bass

Weichsel

Schleuß des Janustempels Türen,

unsre Herzen öffnen wir.

Nächst den dir getanen Schwüren

treibt allein, Herr, deine Güte

unser reuiges Gemüte

zum Gehorsam gegen dir.

4. Rezitativ; Arioso — Tenor

Elbe

So recht! beglückter Weichselstrom!

Dein Schluß ist lobenswert,

wenn deine Treue nur mit meinen Wünschen stimmt,

an meine Liebe denkt

und nicht etwann mir gar den König nimmt.

Geborgt ist nicht geschenkt:

Du hast den gütigsten August von mir begehrt,

deß holde Mienen

das Bild des großen Vaters weisen,

den hab ich dir geliehn,

verehren und bewundern sollst du ihn,

nicht gar aus meinem Schoß und Armen reißen.

Dies schwöre ich,

o Herr! bei deines Vaters Asche,

bei deinen Siegs- und Ehrenbühnen.

Eh sollen meine Wasser sich

noch mit dem reichen Ganges mischen

und ihren Ursprung nicht mehr wissen!

Eh soll der Malabar

an meinen Ufern fischen,

eh ich will ganz und gar dich,

teuerster Augustus, missen!

5. Arie — Tenor

Elbe

Jede Woge meiner Wellen

ruft das göldne Wort August!

Seht, Tritonen, muntre Söhne,

wie von nie gespürter Lust

meines Reiches Fluten schwellen,

wenn in dem Zurückeprallen

dieses Namens süße Töne

hundertfältig widerschallen.

6. Rezitativ — Alt

Donau

Ich nehm zugleich an deiner Freude teil,

betagter Vater vieler Flüsse!

Denn wiße,

daß ich ein großes Recht auch mit an deinem Helden habe.

Zwar blick ich nicht dein Heil,

so dir dein Salomo gebiert,

mit scheelen Augen an,

weil Karlens Hand,

des Himmels seltne Gabe,

bei uns den Reichsstab führt.

Wem aber ist wohl unbekannt,

wie noch die Wurzel jener Lust,

die deinem gütigsten Trajan

von dem Genuss der holden Josephine

allein bewußt,

an meinen Ufern grüne?

7. Arie — Alt

Donau

Reis von Habsburgs hohem Stamme,

deiner Tugend helle Flamme

kennt, bewundert, rühmt mein Strand.

Du stammst von den Lorbeerzweigen,

drum muss deiner Ehe Band

auch den fruchtbarn Lorbeern gleichen.

8. Rezitativ — Sopran

Pleisse

Verzeiht,

bemooste Häupter starker Ströme,

wenn eine Nymphe euren Streit

und euer Reden störet.

Der Streit ist ganz gerecht;

die Sache groß und kostbar, die ihn nähret.

Mir ist ja wohl Lust

annoch bewusst,

und meiner Nymphen frohes Scherzen,

so wir bei unsers Siegeshelden Ankunft spürten,

der da verdient,

daß alle Untertanen ihre Herzen,

denn Hekatomben sind zu schlecht,

ihm her zu einem Opfer führten.

Doch hört, was sich mein Mund erkühnt,

euch vorzusagen:

Du, dessen Flut der Inn und Lech vermehren,

du sollt mit uns dies Königspaar verehren,

doch uns dasselbe gänzlich überlassen.

Ihr beiden andern sollt euch brüderlich vertragen,

und, müßt ihr diese doppelte Regierungssonne

auf eine Zeit, doch wechselsweis, entbehren,

Euch in Geduld und Hoffnung fassen.

9. Arie — Sopran

Pleisse

Hört doch! der sanften Flöten Chor

erfreut die Brust, ergötzt das Ohr.

Der unzertrennten Eintracht Stärke

macht diese nette Harmonie

und tut noch größre Wunderwerke,

dies merkt, und stimmt doch auch wie sie.

10. Rezitativ — Sopran, Alt, Tenor, Bass

Weichsel

Ich muss, ich will gehorsam sein.

Elbe

Mir geht die Trennung bitter ein,

doch meines Königs Wink gebietet meinen Willen.

Donau

Und ich bin fertig, euren Wunsch,

So viel mir möglich, zu erfüllen.

Pleisse

So krönt die Eintracht euren Schluß. Doch schaut,

Wie kommt’s, daß man an eueren Gestaden

so viel Altäre heute baut?

Was soll das Tanzen der Najaden?

Ach! irr ich nicht,

so sieht man heut das längst gewünschte Licht

in frohem Glanze glühen,

das unsre Lust,

den gütigsten August,

der Welt und uns geliehen.

Ei! nun wohlan!

da uns Gelegenheit und Zeit

die Hände beut,

So stimmt mit mir noch einmal an:

11. Chor

Die himmlische Vorsicht der ewigen Güte

beschirme dein Leben, Durchlauchter August!

So viel sich nur Tropfen in heutigen Stunden

in unsern bemoosten Kanälen befunden,

umfange beständig dein hohes Gemüte

Vergnügen und Lust!

This text has been translated with DeepL (www.deepl.com).

Eva Weber-Guskar

What a magnificent birthday song, what a song of praise and worship we are privileged to hear today! Four rivers congratulate the birthday boy, their elector. First they rejoice together, then they quarrel with each other, and finally they are reconciled and come together again. The opening chorus expresses the rivers’ joy at being willing subjects, indeed protégés, of the ruler. It is a joy in several stages: “Creep, playful waves, and murmur softly! No, rush swiftly, that the shore and cliff may resound more often! The joy that stirs our floods, that moves every wave to roar, breaks through the dams […].”

Rivers rarely take on roles in a vocal work (probably in no other cantata at all). It is also rare, if ever, for rivers to be depicted so explicitly as sentient beings in art. But fundamentally, the river is a familiar motif in intellectual history. To go back to a European philosophical source of this motif means going back to the pre-Socratics.

ποταμοῖσι τοῖσιν αὐτοῖσιν ἐμβαίνουσιν ἕτερα καὶ ἕτερα ὕδατα ἐπιρρεῖ

(potamoîsi toîsin autoîsin embainoûsin hétera kaì hétera hýdata epirréi).[1]

Even those who, like me (!), do not understand Ancient Greek may hear something in these words: something hissing, splashing, something moving in waves, something consisting of change and repetition.

ποταμοῖσι τοῖσιν αὐτοῖσιν ἐμβαίνουσιν ἕτερα καὶ ἕτερα ὕδατα ἐπιρρεῖ

(potamoîsi toîsin autoîsin embainoûsin hétera kaì hétera hýdata epirréi).

This is one of the famous river fragments by the philosopher Heraclitus, who lived around 500 BC. In English, we usually only know the abbreviated version of the sentence: “We never step into the same river twice.” The original Greek reveals that rhythm and onomatopoeia were also important to Heraclitus when writing, which are lost in the rough paraphrase.

You have already heard about the rhythm and tones of today’s cantata in the introduction to the work. I would like to take this secular cantata, in which rivers sing, as an opportunity to talk to you about rivers and people. What do they have in common? Or, to put it another way, what can the image of the river teach us about ourselves?

The first thing that comes to mind is perhaps that the river represents the flow of life; the life energy that flows within us; or the unconditional striving in all living things, which the philosopher Baruch de Spinoza in the early modern period called conatus, for example. In contrast, many people today, in our era marked by climate change, may think of rivers suddenly bursting their banks and becoming raging torrents, bringing destruction and death in their wake.

But there is more to the image of the river than the association of life and death. Why exactly did Heraclitus speak of the river? And where does one end up when one thinks beyond it with Heraclitus? It seems to me that the image is a good starting point for reflecting on human temporality.

“We never step into the same river” initially sounds like an addition to another fragment by Heraclitus: πάντα ῥεῖ (pantha rhei), everything flows. This would simply assert that there is no permanence in the world, but that everything is constantly changing. However, the original, which I read to you earlier in Greek, translates literally as something different, namely: “For those who step into rivers that remain the same, other and different water flows.”

According to this formulation, it is entirely possible to step into the same river twice. Only the water flowing in it is always different. This is Heraclitus’ understanding of unity and change, which he saw prevailing throughout the cosmos: every unity, all being, is not only possible despite change, but units exist by virtue of change. The river is a particularly apt image for this. A river consists of water that is in motion. The river does not remain the same at any single point, but only as a whole. It consists of drops that are constantly changing their location. Perhaps you have visited a waterfall before, such as the Giessbach Falls. I recently had the opportunity to admire them for the first time. There, at the point where you can step behind the waterfall, it is particularly striking: if you hold your head straight, the water falls in front of you as a whole river. But if you pick out a large drop from the splashing water with your eyes and follow it by moving your head from top to bottom, you will see one of the countless parts in motion that make up the river as a whole.

Heraclitus’ fragment is so cleverly worded in the original that it can also be translated in a second way, namely as follows: “To those who step into rivers and remain the same, other and other water flows.” “Remain the same” can therefore refer not only to rivers, but also to the beings that enter the rivers – that is, to us humans. Therefore, it can also be interpreted to mean that what applies to rivers also applies to humans. Here: the direct connection between change and unity. But how can this be understood more precisely?

First, one could understand it biologically. Only through constant metabolism, which converts substances, namely starch into energy, and only through blood flow can an organism remain intact as a whole. However, this applies not only to humans, but also to animals; to mice, squirrels or elephants, to name but three. (Strictly speaking, one should refer to human and non-human animals, but for the sake of simplicity, I will stick to the everyday distinction between humans and animals.)

One of the things that distinguishes humans from animals is their ability to relate to the other two dimensions of time beyond the present: the past and the future. Squirrels may vaguely remember where they hid their nuts in autumn, but that is hardly more than a year ago. Elephants can mourn deceased family members for quite some time, and primates can plan hours or even days ahead. But our temporal extension surpasses all of that.

Our connection to the past extends back to childhood. Indeed, it can even extend beyond that – and I am not referring to the realm of platonic souls before birth. Our connection to the past is more than just memory. For example, my grandmother and her life belong to this dimension of connection to the past for me.

My grandmother grew up on the Altmühl, a small river in southern Germany, and she loved swimming in it in the summer. Her father was a pastor and often took her with him on his rounds to confirmation classes in the surrounding villages, where he literally told her about God and the world. When I was a child, my grandmother told me all about this, gave me books to read – and discussed in a friendly but not uncritical manner the attempt to prove the existence of God that had occurred to me at the age of nine, which I had written down on a piece of paper and shown to her. It remained my only attempt. I chose to study philosophy rather than theology. And yet I am somewhat in the tradition of my grandmother and my great-grandfather. I understand myself from a past that goes back further than my childhood. Much of what I do is motivated not least by my admiration and love for my grandmother, who died long ago; she who lived on the outskirts of Leipzig during the Second World War and walked through the bombed-out city to St. Thomas Church to listen to Bach’s cantatas.

Our relationship to the future, on the other hand, manifests itself in desires, plans and expectations, as well as in feelings such as hope or fear. Above all, however, our relationship to the future extends to our death. Unlike animals, we know that we will die once we reach a certain age.

If this conscious extension over time constitutes human existence, to what extent can Heraclitus’ idea of unity in constant flux be found in it? To answer this, we need only realise that we do not view the past and future from a fixed point of view. Rather, our position changes constantly throughout our lives. At least with every phase of life. In our youth, we have grand ideas about what we want to become and think little about the past. As adults, if we are fortunate, we strive for lasting stability, building on what we have achieved while also making provisions for the future. In old age, we may focus on what we can pass on to the next generation from our wealth of experience, so we look back more, and when we look ahead, it is often beyond our own lives. In all phases of life, we obviously always relate to the past and future in different ways from the present. In constant change.

But what does it mean not only to lead a human life, to which this particular temporality belongs, but what does it mean to lead a good life in this respect? With this question, I go beyond Heraclitus into the realm of ethics. As described, there are different focal points depending on the stage of life, which arise simply from how much of the past one can look back on or not, as children and the elderly differ greatly in this respect. But at any age, we can focus more or less on the past, present and future. What practice would be advisable in this regard to make our lives successful?

The idea that one should focus primarily on the present is quite widespread. Cárpe díem, as Horace wrote, “Immerse yourself in the now,” as we hear in meditation seminars. But on the one hand, it is difficult to say exactly what that means in detail. How long does the present last if it is to be more than the transition from one moment to the next? On the other hand, it would mean neglecting what is specifically human: the ability to comprehend oneself across time. Therefore, while it is certainly good to experience certain moments intensely, meditation is about much more than immersing oneself in the present. But as a more general attitude, it seems advisable to strive for a balanced relationship. In this case, ‘balanced’ means paying just as much attention to the past, present and future as is necessary to maintain a healthy relationship with each of these dimensions.

Dealing with the past in such a way that it does not obstruct either the present or the future means, above all, not allowing oneself to be held back by extreme regret, remorse, guilt or trauma from the past. All these attitudes or states can prevent one from experiencing the present vividly and making plans for the future. Those who constantly dwell on past suffering become blind to the possibilities of forgiveness, reconciliation and new beginnings. Resting proudly on one’s laurels also limits one’s perspective on new things.

Relating to the present in a balanced way means experiencing the present, what is happening to you, as something that is happening to you as the specific person you were before and will be later. It can help to insert the event into a story that you can or could tell about your life. In this story, experiences and events take on a value that is determined, among other things, by their place in the story. A missed train, for example, will initially be simply an annoyance – but if you have an encounter on the next train that leads to a professional or personal relationship, or even just the experience of a particularly beautiful sunset through the window, then the event becomes part of a story and takes on a positive value in retrospect (unfortunately, this also works with negative values, of course).

In order to live up to one’s potential, one should ultimately view the future not only as an impending fate, but also as an opportunity for actions that one initiates oneself. This openness to the future should, of course, be limited by continuing to take past experiences into account, for example in order to learn from mistakes.

With such a balanced relationship to the three dimensions of time, each of which is given its due, a fulfilled present can be achieved. A present that stands apart from what was and what will be, and yet could not exist without either of them. A present, as we can say with today’s cantata text, in which the past still murmurs and in which one plays with plans for the future.

Let us now continue to listen to the conversation between the rivers and experience where the music carries our thoughts. Perhaps you will also experience a little of the unity that is always in flux, of which Heraclitus spoke in his river fragments.

[1] Heraclitus, Fragment B12. For the interpretation included here, see: Graham, Daniel W., “Heraclitus,” The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Winter 2023 Edition), Edward N. Zalta & Uri Nodelman (eds.), URL = https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/win2023/entries/heraclitus/; Kahn, Charles H., 1979, The Art and Thought of Heraclitus, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.