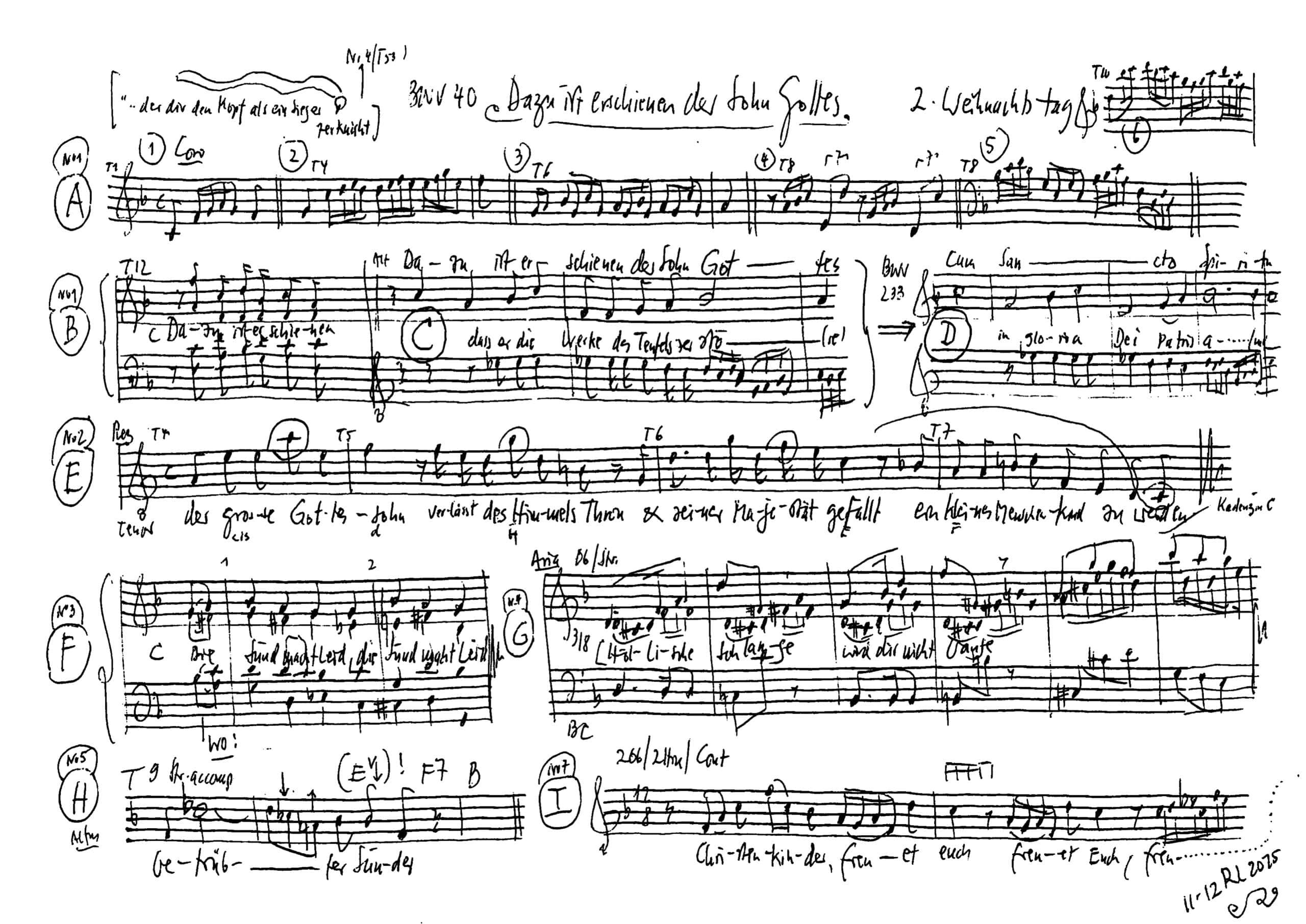

Darzu ist erschienen der Sohn Gottes

BWV 040 // For the Second Day of Christmas (St Stephen)

(For this is appeared the Son of God) for alto, tenor and bass, vocal ensemble, horn I+II, oboe I+II, strings and basso continuo

Place of composition in the church year

Pericopes for Sunday

Pericopes are the biblical readings for each Sunday and feast day of the liturgical year, for which J. S. Bach composed cantatas. More information on pericopes. Further information on lectionaries.

Singet dem Herrn ein neues Lied; denn er tut Wunder. Er siegt mit seiner Rechten und mit seinem heiligen Arm. Der Herr lässt sein Heil verkündigen; vor den Völkern lässt er seine Gerechtigkeit offenbaren. Er gedenkt an seine Gnade und Wahrheit dem Hause Israel; aller Welt Enden sehen das Heil unseres Gottes.

Da aber erschien die Freundlichkeit und Leutseligkeit Gottes, unseres Heilandes – nicht um der Werke willen der Gerechtigkeit, die wir getan hatten, sondern nach seiner Barmherzigkeit machte er uns selig durch das Bad der Wiedergeburt und Erneuerung des Heiligen Geistes, welchen er ausgegossen hat über uns durch Jesum Christum, unseren Heiland, auf dass wir durch desselben Gnade gerecht und Erben seien des ewigen Lebens nach der Hoffnung.

Und als die Engel von ihnen gen Himmel fuhren, sprachen die Hirten untereinander: «Lasst uns nun gehen gen Bethlehem und die Geschichte sehen, die da geschehen ist, die uns der Herr kundgetan hat.» Und sie kamen eilend und fanden beide, Maria und Joseph, dazu das Kind in der Krippe liegen. Da sie es aber gesehen hatten, breiteten sie das Wort aus, welches zu ihnen von diesem Kinde gesagt war. Und alle, vor die es kam, wunderten sich der Rede, die ihnen die Hirten gesagt hatten. Maria aber behielt alle diese Worte und bewegte sie in ihrem Herzen. Und die Hirten kehrten wieder um, priesen und lobten Gott um alles, was sie gehört und gesehen hatten, wie denn zu ihnen gesagt war.

Choir

Soprano

Alice Borciani, Cornelia Fahrion, Linda Loosli, Susanne Seitter, Noëmi Tran-Rediger, Alexa Vogel

Alto

Antonia Frey, Francisca Näf, Jan Thomer, Lisa Weiss, Sarah Widmer

Tenor

Clemens Flämig, Manuel Gerber, Sören Richter, Walter Siegel

Bass

Fabrice Hayoz, Daniel Pérez, Julian Redlin, Peter Strömberg, Tobias Wicky

Orchestra

Conductor

Rudolf Lutz

Violin

Renate Steinmann, Monika Baer, Patricia Do, Lisa Herzog-Kuhnert, Olivia Schenkel, Salome Zimmermann

Viola

Susanna Hefti, Claire Foltzer, Stella Mahrenholz

Violoncello

Martin Zeller, Bettina Messerschmidt

Violone

Markus Bernhard

Oboe

Andreas Helm, Amy Power

Bassoon

Susann Landert

Horn

Stephan Katte, Thomas Friedlaender

Harpsichord

Thomas Leininger

Organ

Nicola Cumer

Musical director & conductor

Rudolf Lutz

Workshop

Participants

Rudolf Lutz, Pfr. Niklaus Peter

Reflective lecture

Speaker

Eva von Redecker

Recording & editing

Recording date

19/12/2025

Recording location

St. Gallen (Switzerland) // Protestant Church St. Mangen

Sound engineer

Stefan Ritzenthaler

Producer

Meinrad Keel

Executive producer

Johannes Widmer

Production

GALLUS MEDIA AG, Schweiz

Producer

J.S. Bach-Stiftung, St. Gallen, Schweiz

Librettist

First performance

26 December 1723 in Leipzig

Poet unknown

Movement 1: 1 John 3:8

Movement 3: “”Wir Christenleut”” (Caspar Füger, 1592), verse 3

Movement 6: “”Schwing dich auf zu deinem Gott”” (Paul Gerhardt, 1653), verse 2

Movement 8: “”Freuet euch, ihr Christen alle”” (Christian Keymann, composed around 1645; first printed in 1646), movement 4 (printed by Döbeln 1736)

Libretto

1. Chor

«Dazu ist erschienen der Sohn Gottes, daß er die Werke des Teufels zerstöre.»

2. Rezitativ — Tenor

Das Wort ward Fleisch und wohnet in der Welt,

das Licht der Welt bestrahlt den Kreis der Erden,

der große Gottessohn

verläßt des Himmels Thron,

und seiner Majestät gefällt,

ein kleines Menschenkind zu werden.

Bedenkt doch diesen Tausch, wer nur gedenken kann:

Der König wird ein Untertan,

der Herr erscheinet als ein Knecht

und wird dem menschlichen Geschlecht,

o süßes Wort in aller Ohren!

zu Trost und Heil geboren.

3. Choral

Die Sünd macht Leid;

Christus bringt Freud,

weil er zu Trost in diese Welt ist kommen.

Mit uns ist Gott

nun in der Not:

Wer ist, der uns als Christen kann verdammen!

4. Arie — Bass

Höllische Schlange,

wird dir nicht bange?

höllische Schlange?

Der dir den Kopf als ein Sieger zerknickt,

ist nun geboren,

und die verloren,

werden mit ewigem Frieden beglückt.

5. Rezitativ — Alt

Die Schlange, so im Paradies

auf alle Adamskinder

das Gift der Seelen fallen ließ,

bringt uns nicht mehr Gefahr;

des Weibes Samen stellt sich dar,

der Heiland ist ins Fleisch gekommen

und hat ihr allen Gift benommen.

Drum sei getrost! betrübter Sünder.

6. Choral

Schüttle deinen Kopf und sprich:

Fleuch, du alte Schlange!

Was erneurst du deinen Stich,

machst mir angst und bange?

Ist dir doch der Kopf zerknickt,

und ich bin durchs Leiden

meines Heilands dir entrückt

in den Saal der Freuden.

7. Arie — Tenor

Christenkinder, freuet euch!

Wütet schon das Höllenreich,

will euch Satans Grimm erschrecken:

Jesus, der erretten kann,

nimmt sich seiner Küchlein an

und will sie mit Flügeln decken.

8. Choral

Jesu, nimm dich deiner Glieder

ferner in Genaden an;

schenke, was man bitten kann,

zu erquicken deine Brüder:

Gib der ganzen Christenschar

Friede und ein selges Jahr!

Freude, Freude über Freude!

Christus wehret allem Leide.

Wonne, Wonne über Wonne!

Er ist die Genadensonne.

This text has been translated with DeepL (www.deepl.com).

Eva von Redecker

Dear, esteemed audience

I would like to say that it is a great honour for me to speak to you here, but recently an elderly, learned Marxist – Wolfgang Fritz Haug – pointed out to me[1] that ‘honour’ is a feudal category. I should say ‘a pleasure’. And that fits in perfectly with the last notes we have just enjoyed: joy, joy upon joy! / Christ wards off all suffering. / Joy, joy upon joy! / He is the sun of mercy. I will return to the specific joy of the Christmas miracle, but first I would like to say that it is a great joy to be in this enchanting place and listen to Bach’s incomparable music. And I cannot quite shake off the feeling of honour. Even if I am not being honoured, I am still in awe. It is quite intimidating to have to find new meaning in a work that has been valid for over three centuries. Especially since I can assure you that, as much as I delight in music, I understand little about it.

Fortunately, a church cantata like this has a text. And in this case, number 40 in the Bach Works Catalogue, it also has a direct occasion. Johann Sebastian Bach wrote the piece for performance in Leipzig on Boxing Day 1723. His librettist drew on words from the Bible and from earlier masters of Baroque church music such as Paul Gerhardt and Caspar Füger. And the resulting message is extremely rich, almost philosophical. For on 26 December, it is no longer about the proclamation of the Christmas miracle, not about the revelation – “behold, a child is born unto us” – but about its interpretation. For this reason, the Son of God was born… For this reason, which answers the question “Why?” We are to learn the purpose for which Jesus came into the world. What is the meaning and significance, the “why and wherefore” of Christ’s birth? The religious meaning, the meaning for Christians. This joyful Christmas cantata thus leads us directly into theology.

Perhaps you expected that an unbelieving feminist philosopher who is taught by old Marxists would leave religion aside here today. That was also my job description: “No theological interpretation is explicitly required. Instead, poetic, philosophical, personal interjections and moments of reflection are requested, freely floating from the text of the cantata,” wrote my wonderful colleague Barbara Bleisch. And that’s roughly what I had announced, in a hurry and on request, that I would say “something about Hannah Arendt and natality”. I will come to that. But let me start differently.

We are currently experiencing something so bizarre, so absurd to secular thinkers and modern devout Christians alike, that it is difficult to even acknowledge it. Politics is once again being conducted in the name of Christianity. Ruthless politics, and on the grand stage of world history. It fits so poorly with our ideas of enlightenment, of the secular separation of church and state, of cosmopolitanism, that we may not yet fully comprehend it. But even a cursory review of the situation reveals a number of clues. One of the richest and most influential tech billionaires in US politics, Peter Thiel, aggressively advocates the view that we are in an apocalyptic final battle in which technology opponents and Greta Thunberg are playing the role of the Antichrist, while the aggressive West under Trump is the Katechon: the force that stands against destruction. Evangelical Christian end-time beliefs also play a role in the Middle East conflict. Christian Zionists believe that before they themselves are damned as infidels, the Jews should gather in a Jerusalem freed from pagans, because only then will Jesus return. They have a large base – larger than that of Jews in the US, many of whom are also critical of Israel’s policies – and support the policy of extermination against Palestinians as part of a holy war. Pete Hegseth, the US “war minister”, actually has a crusade symbol tattooed on his back. And politics in Texas is significantly influenced by an oil tycoon named Tim Dunn, who believes that the petroleum that made him rich was placed on the newly created earth by God six thousand years ago. So it is anything but irrelevant why the Son of God appeared.

When we turn to the cantata with curiosity to learn more about the answer, however, we are initially met with a certain disappointment. This wonderful cantata contains some of the crudest images in the entire Christian tradition. The answer seems almost reactive. The immediate response is that he destroys the works of the devil. Jesus as destroyer and avenger – is that the meaning of the Gospels? Hellish serpent, / Are you not afraid? / He who will crush your head as a victor / Is now born. A magnificent alto aria, but is that supposed to be the joy of Christmas, mere rejoicing over triumph? Forgive my vehemence, but these texts are imbued with a hint of the oldest and most widespread sectarianism in Christianity: Manichaeism. In places, the libretto sounds like a dualistic plot in which two fundamentally different forces fight an apocalyptic battle. Here the devil, there God; here the serpent, there Jesus; here the woman, there the Christian. A battle of good against evil: fury, poison and twice the head crushed. Good triumphs, evil is destroyed, and the innocent children can seek refuge under the wings of the mother hen, the Son of God. If Satan’s wrath frightens you: / Jesus, who can save, / Takes care of his little ones / And wants to cover them with his wings.

This is set to music in a gifted way, but if one reads it in the sense just outlined, then it is heresy. It is heresy from a Christian point of view because it conceives of evil as an independent force and good merely as its opponent. And it is heresy from a materialistic point of view because it deprives people of their freedom. Certainly, one should sometimes find refuge in faith, like a fluffy chick under a wing. But that is not why Jesus was born. He was born to redeem mankind. Redeeming people as Christians is different from separating light from dirty matter, as Manichaeism preaches. This eclectic doctrine, which drew on early Christianity, Zoroastrianism and Buddhism, was brutally persecuted during the late antique consolidation of the Christian religion, especially by its former follower, the Church Father Augustine. Nevertheless, Manichaean fanaticism also had a profound influence on Christianity. This is often the case with ideas that are persecuted. We should be wary of this. Augustine in particular preaches in many places a radical renunciation of the world, mercilessness and an ever-present misogynistic hatred of the body. And something of this also resonates in our cantata, for example in the second recitative, where the serpent’s venom falls on Adam’s children and is associated with the woman’s seed.[2]

To identify the devilish in this way in the feminine is repugnant, especially if your name is Eve. Don’t say poison, I would like to say to the cantata poets. It is called will. Don’t say sin. It is called desire. Daniela Seel, a contemporary poet, summed up this counterargument succinctly. In her long poem Nach Eden (After Eden), written in 2024, she writes the following lines about Eve: “Take Eve seriously. In her curiosity and her hunger for knowledge, / in her judgement, in her desire to eat, to share, in her / responsibility. Eve, who knew what she was doing when she ate. God / had told her. The serpent had told her.”[3]

“Eve, who knew what she was doing when she ate.” Is this simply the opposite heresy? The objection to old and new Manichaeism in the name of secular reason and female humanity? Is it even witchcraft? That’s fine with me. Better to be in hell with an apple than in paradise without a thirst for knowledge. But something is still wrong if we move too bluntly to this perspective. It suggests alternatives as if we were still in the Garden of Eden, as if we did not know that history had long since moved on after the question of “to bite or not to bite”. Something else happened. The Son of God appeared… Seel’s lines are set “after Eden”. Could they also be set in Bethlehem?

To answer that, we must finally clarify what Bethlehem actually means. That God becomes a defenceless human child is striking at first, because God so demonstratively gives up his feudal position of honour. Consider this exchange, / whoever can remember it; / The king becomes a subject, / The Lord appears as a servant. This loving devotion of God also reveals something about humanity and earthly life. Its form, in all its finiteness and sensuality, is capable of grasping the divine. The Word became flesh and dwelt in the world. This is the first facet of the Christmas miracle. It gives cause for wonder and rejoicing – O sweet word in all ears!

The Protestant socialist theologian Paul Tillich, who in 1933 was one of the first to be stripped of his professorship by the National Socialists and fled into exile in America, describes the core of the Christian message as “that being can be universal in the concrete”.[4] He does not believe that one must take any Bible stories literally – he even classifies such belief as “myth” and equates it with superstition. But one must believe the following: that something can be found in a completely insignificant thing that transcends everything that exists, that comforts and heals and makes things exist in the first place and allows them to be themselves.

For Tillich, trained in Aristotle and Augustine, God is being. Not a particularly elevated, distinguished thing among other things, not something that exists somewhere, but “being itself.”[5] “Being is not the highest form of existence, but that which makes existence possible in the first place,” he writes ([6] ), or also: “the power of being, or the reason for being, or the meaning of being.” ([7] ) God does not stand opposite the serpent, but opposite the abyss of complete non-being, a universe in which there is nothing, neither us nor the serpent nor God. And no universe either. It is impossible to think this through to its conclusion, which is why there is such comfort in affirming the primordial positive. That is, believing in God.

But as a Christian, one does not only believe in God, one also believes in Jesus Christ. And his arrival transforms existence. The core of the Christian message, as we have heard, is that God, i.e. the universality that saves us from the empty non-universe, can also be present in concrete terms. That subjects, servants, infants, and in principle also Eve, the apple and the serpent can be home to God. In Tillich’s terms, this overwhelmingly joyful insight transforms being into a “new being”. This new being, according to his interpretation of Christmas, should become the central concept of Christian theology.[8]

The New Being restores something that had fallen apart due to stubborn human actions in the earthly world. Augustine calls this disintegration sin. But Tillich does not like the undertone of mere disobedience, of a violation of a commandment. As if God were the real ruler after all. Tillich calls it instead “essential transgression”:[9] that our existence deviates from the divine essence, which should also be ours. It is not a relationship of obligation that connects us to God, but a relationship of being. We can participate in the divine. And while we fail to do so – a failure captured in the myth of paradise – God makes the opposite move and takes on creaturely form, proving to us that he dwells within us, even when we stray from the path.

If we want to confirm this acceptance, this divine acceptance of our form, we must strive to overcome our alienation from our essence. For Augustine, the answer to the intimidating question of how one can belong to the kingdom of God is quite simple: “by longing for it”. Tillich speaks of a return to love, “to that which stands beyond the division of essence and existence in all that exists.”[10] Participation consists in being moved by God, who has already come to meet us. When reading Tillich, the category of being moved did not seem particularly clarifying to me. But when you hear Bach in a church like this, you know exactly what it means.

True salvation, however, consists in the fact that, thanks to Jesus’ birth and teachings, the fulfilment of our essence, i.e. participation in the divine, does not conflict with our freedom. Hannah Arendt, who was a friend of Paul Tillich and also closely connected to him through their mutual lover Hilde Fränkel, gave a wonderful description of why Jesus can be understood as the epitome of the possibility of freedom. The first thing is the fact of his birth. For it shows that something new is possible. “The miracle that repeatedly interrupts the course of the world and the course of human affairs and saves them from ruin (…) is birth,” she writes in Vita activa.[11] Following this example, every human action also has an unpredictable beginning. However, the consequences of actions are also unpredictable, especially for humans. That is why, secondly, we need a way to renounce false beginnings. Otherwise, with every free new beginning, we would immediately become entangled in bondage again. We would not be able to escape the consequences. But there is a remedy: forgiveness, i.e. the possibility of being absolved of responsibility. “Only through this constant mutual exoneration and release can people who come into the world with the dowry of freedom remain free in the world,” as Arendt puts it.[12] Freedom is not poison; it is a dowry that we must cherish.

Without the opportunity to take responsibility for wrongdoing, to reconsider, to ask for forgiveness, Eve’s choice could not really be approved of in retrospect. With this opportunity, however, it can. Seel writes that Eve knew what she was doing, that she had the capacity for judgement. Eva did not eat the apple like a snake eats a mouse, not out of instinct, not indiscriminately. That would be sin, a transgression of her nature, a lack of freedom. And so judgement and knowledge can continue to accompany desire, eating and sharing. Temptation does not lead to irresolvable entanglement. That is true, at least according to Bethlehem. It is precisely in being free, in being able to act, that our existence becomes worthy of its essence. For this reason, the Son of God appeared: so that we can be free and curious, listen to the serpent and thereby participate in God’s nature.

Joy is preferable to honour. But perhaps even higher than joy is delight: as an intimate joy that harbours freedom. In any case, that would be my listening recommendation if we are now allowed to listen to the cantata a second time: that you pay attention to the places in the music where joy turns into delight. And then wait for the promising passage at the end of the cantata where the bliss remains suspended in the air without musical resolution. It does not disappear into heavenly harmony – it relies on its ability to move us.

[1] Wolfgang Fritz Haug said that Erich Fromm had reprimanded him in this way decades earlier.

[2] The talk of female semen, which may sound strange to modern ears, stems from the early modern idea of a single-gender model. The female reproductive organs were understood anatomically as a less perfect (moister, cooler) variant of the male form, which was merely turned inwards. “Semen” is therefore unisex here. Incidentally, the notion of sperm as semen, which emerged in the 18th century and is still common today, is highly misleading: the child is created in the female body from two germ cells, whereas semen contains all the genetic information and is merely nourished by the earth as it grows. See: Thomas Laquer (1992): Gendered Bodies: The Construction of Sex from Antiquity to Freud; Claudia Honegger (1991): The Order of the Sexes: The Sciences of Man and Woman, 1750–1850; both published by Campus, Frankfurt am Main.

[3] Daniela Seel (2024): Nach Eden (After Eden). Suhrkamp, Berlin, p. 7.

[4] Paul Tillich (2018 [1955]): Das Neue Sein als Zentralbegriff einer christlichen Theologie (The New Being as a Central Concept of Christian Theology), in: Ibid.: Rechtfertigung und Neues Sein (Justification and New Being), ed. Christian Danz. Christliche Verlagsanstalt, Leipzig, pp. 35–64, here p. 50.

[5] Tillich: The New Being, p. 40.

[6] Ibid., p. 39.

[7] Ibid., pp. 48–49.

[8] Ibid., p. 35.

[9] Ibid., p. 42.

[10] Ibid., p. 56.

[11] Hannah Arendt (1981[1958]): The Human Condition. Piper, Munich, p. 243.

[12] Ibid., p. 235.