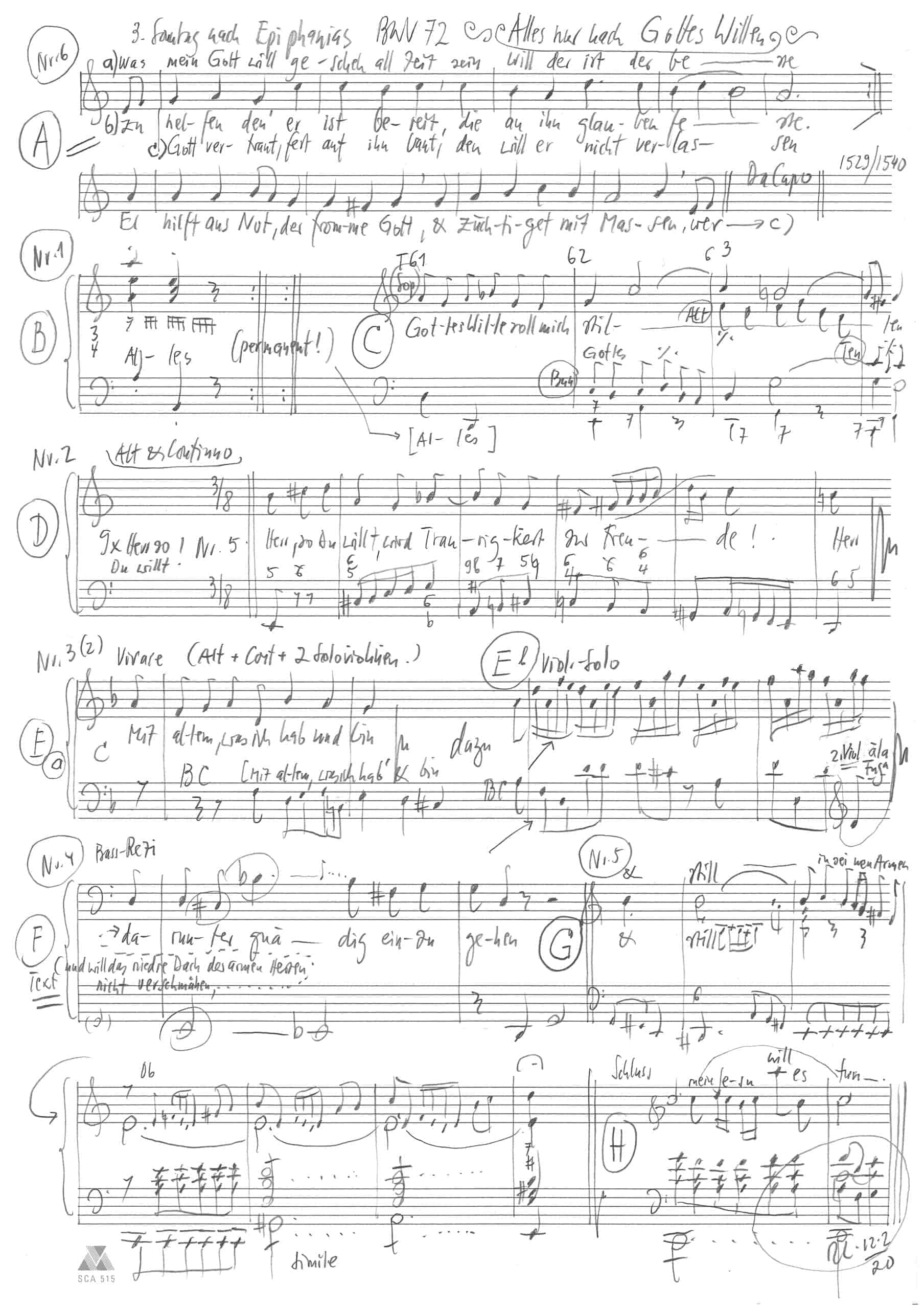

Alles nur nach Gottes Willen

BWV 072 // For the Third Sunday after Epiphany

(All things but as God is willing) for soprano, alto and bass, vocal ensemble, oboe I+II, strings and basso continuo

Would you like to enjoy our videos ad-free? Subscribe to YouTube Premium now...

Workshop

Reflective lecture

Choir

Soprano

Simone Schwark, Susanne Seitter, Noëmi Tran-Rediger, Alexa Vogel, Anna Walker, Mirjam Wernli

Alto

Roland Faust, Francisca Näf, Lea Pfister-Scherer, Lisa Weiss, Sarah Widmer

Tenor

Clemens Flämig, Zacharie Fogal, Tobias Mäthger, Klemens Mölkner

Bass

Fabrice Hayoz, Grégoire May, Simón Millán, Philippe Rayot, Tobias Wicky

Orchestra

Conductor

Rudolf Lutz

Violin

Eva Borhi, Lenka Torgersen, Peter Barczi, Christine Baumann, Petra Melicharek, Dorothee Mühleisen, Ildiko Sajgo

Viola

Martina Bischof, Matthias Jäggi, Sarah Mühlethaler

Violoncello

Maya Amrein, Daniel Rosin

Violone

Markus Bernhard

Oboe

Andreas Helm, Ingo Müller

Bassoon

Gilat Rotkop

Harpsichord

Jörg-Andreas Bötticher

Organ

Nicola Cumer

Musical director & conductor

Rudolf Lutz

Workshop

Participants

Rudolf Lutz, Pfr. Niklaus Peter

Reflective lecture

Speaker

Roman Bucheli

Recording & editing

Recording date

14/02/2020

Recording location

Trogen AR (Schweiz) // Evangelische Kirche

Sound engineer

Stefan Ritzenthaler

Producer

Meinrad Keel

Executive producer

Johannes Widmer

Production

GALLUS MEDIA AG, Schweiz

Producer

J.S. Bach-Stiftung, St. Gallen, Schweiz

Librettist

First performance

27 January 1726, Leipzig

Text

Salomo Franck (no. 1 – 5),

Duke Albrecht von Preussen (no. 6)

In-depth analysis

Composed for the Third Sunday after Trinity in 1726, cantata BWV 72 “Alles nur nach Gottes Willen” (All things but as God is willing) forms part of the annual cycle of that year, which becomes stylistically more diverse as it proceeds. At the same time, the work’s introductory chorus is similar in compositional form to its sister work “Was mein Gott will” (What my God will, BWV 111) written one year earlier, particularly in regard to the twonote vocal gesture on the word “Alles” (all). In our cantata, this is set as a series of staccato leaps of fourths which are immediately counterpointed in an intricate semiquaver coloratura, thus highlighting both the emphatic message and the potent efficacy of the motto. The fact that Bach reworked this powerful composition in the 1730s as the Gloria for his Mass in G Minor BWV 235 speaks volumes about his understanding of quality as well as his skill in compositional transformation.

The following alto recitative then explores in detail the general claim of the opening movement. Here, the arioso setting of the motto “Herr, so du willt” (Lord, if Thou willt) is reminiscent of the aria of the same name from BWV 73, which was composed in 1724 for the same Sunday in the church year. In our cantata, however, prominence is given to the optimistic thoughts on awakening and healing rather than the theme of preparing for death that dominates the earlier work.

Accordingly, the following aria also focuses on earthly life, opening with a confessional statement by the alto voice “Mit allem, was ich hab und bin, will ich mich Jesu lassen” (With ev’rything I have and am, I’ll trust myself to Jesus), which segues into a virtuoso violin duet. Throughout this setting, the dimension of temptation is as palpable as the immense inspiration to commit to living life in the spirit of Jesus – as such, the “Dornen und Rosen” (thorns and roses) described in the libretto form an inextricable whole.

The bass recitative then shows how such trust born of experience might sound, which is summarised in Jesus’s weighty promise “Ich will’s tun” (This will I). Thus inspired, the dance-like albeit gently flowing soprano aria “Mein Jesus will es tun” (My Jesus will do it) transforms these notions of hopeful faith into enchanting musical gestures; for its part, the obbligato oboe breathes an expansiveness and a tender sense of commitment into the setting. Through a skilful fermata, Bach plays with the equally decelerating and afterworld-oriented significance of the keyword “ruhn” (rest), ere the unusually gestural closing phrase, without a coda, underscores the earthly relevance and presence of the divine promise: not only does this saviour wish to “sweeten thy cross” (dein Kreuz versüssen) in a general sense – he will actually follow through, now for each and every one of his believers. That the flowing closing chorale “Was mein Gott will, das g‘scheh allzeit” (What my God will, be done alway) then follows quasi-attacca with the unified voices representing the congregation of believers forms an essential part of the consolation inherent in this cantata.

Libretto

1. Chor

Alles nur nach Gottes Willen,

so bei Lust als Traurigkeit,

so bei gut als böser Zeit.

Gottes Wille soll mich stillen

bei Gewölk und Sonnenschein.

Alles nur nach Gottes Willen,

dies soll meine Losung sein.

2. Rezitativ / Arioso — Alt

O selger Christ,

der allzeit seinen Willen

in Gottes Willen senkt,

es gehe, wie es gehe,

bei Wohl und Wehe!

Herr, so du willt, so muß sich alles fügen!

Herr, so du willt, so kannst du mich vergnügen!

Herr, so du willt, verschwindet meine Pein!

Herr, so du willt, werd ich gesund und rein!

Herr, so du willt, wird Traurigkeit zur Freude!

Herr, so du willt, find ich auf Dornen Weide!

Herr, so du willt, werd ich einst selig sein!

Herr, so du willt, laß mich dies Wort im Glauben fassen

und meine Seele stillen!

Herr, so du willt, so sterb ich nicht,

ob Leib und Leben mich verlassen,

wenn mir dein Geist dies Wort ins Herze spricht!

3. Arie — Alt

Mit allem, was ich hab und bin,

will ich mich Jesu lassen,

kann gleich mein schwacher Geist und Sinn

des Höchsten Rat nicht fassen.

Er führe mich nur immerhin

auf Dorn und Rosenstraßen.

4. Rezitativ — Bass

So glaube nun!

Dein Heiland saget: Ich wills tun!

Er pflegt die Gnadenhand

noch willigst auszustrecken,

wenn Kreuz und Leiden dich erschrecken.

Er kennet deine Not, und löst dein Kreuzesband!

Er stärkt, was schwach,

und will das niedre Dach

der armen Herzen nicht verschmähen,

darunter gnädig einzugehen.

5. Arie — Sopran

Mein Jesus will es tun, er will dein Kreuz versüßen.

Obgleich dein Herze liegt in viel Bekümmernissen,

soll es doch sanft und still in seinen Armen ruhn,

wenn es der Glaube faßt; mein Jesus will es tun.

6. Choral

Was mein Gott will, das g’scheh allzeit,

sein Will, der ist der beste,

zu helfen den’ er ist bereit,

die an ihn glauben feste.

Er hilft aus Not, der fromme Gott,

und züchtiget mit Maßen.

Wer Gott vertraut, fest auf ihn baut,

den will er nicht verlassen.

The invisible hand of God

Roman Bucheli

Everything only according to God’s will. What was Bach thinking when he wrote his ravishing music for this first verse of the cantata? Perhaps, ladies and gentlemen, perhaps you were like me and caught yourself thinking: “I hear the message, but do I know what it means: Everything only according to God’s will? Or asked differently and heretically: did Bach know what was meant, did people know in Bach’s time?

Allow me to elaborate a little. And don’t be alarmed if I now go very far. I’ll start with the hand of God. You think that’s not so far out of our way? Take a look for yourself!

If video evidence had been available at the 1986 World Cup in Mexico, the legendary goal scored by Diego Maradona with his hand would never have been recognised, Argentina might not have won against England, the team would not have reached the final and Maradona would not have become world champion. And believe me, none of that should bother us. But if the referee hadn’t fallen for the mischievous football genius, we would be missing a sentence today with which Maradona wrote the history of ideas. He added its most beautiful postscript to metaphysics. Questioned after the match, Maradona would not fully deny that he had cheated, but only a little at most. To the inquisitorial questions as to whether it was actually his head or rather his hand that had guided the ball into the goal, he replied with this grandiose sentence: “It was a bit of Maradona’s head and a bit of God’s hand.” (Or in the original: “Un poco con la cabeza de Maradona y otro poco con la mano de Dios.”) In other words, it was a collaboration of human genius and divine manufacture. It was not their impudence that made Maradona’s answer a bon mot for the history books. Rather, the punchline lies in the fundamental reversal of the relationship between God and man. Until then, man had been considered an instrument of God, but here it is just the other way round. God’s hand comes to the rescue where Maradona’s head wants it, because he can no longer reach it himself. God assists the genius of man with a handout: this is the division of labour in the secularised world. Who, for God’s sake, still talks about God’s will? All that counts is what the head, the genius or – in its emblematically modern form – the I written in capital letters wants.

So what was Bach thinking when he wrote the cantata, and what were people thinking when they heard the cantata Alles nur nach Gottes Willen in Leipzig on the third Sunday after Epiphany in January 1726?

If we wanted to be malicious, we could conjecture that people at that time had recognised God’s will in everything that was the case and thus their doom, because it was unchangeable. This included the fact that in 1726, the 16-year-old Louis XV took up his reign in France and would thereafter exercise absolutist rule for many decades. Another irrefutable fact was that in the same year Duke August I, known as the Strong (if that wasn’t an I in capital letters!), had been on the throne for over thirty years and, with all the Baroque splendour he could muster, staged himself as prince and ruler of Saxony (and thus also Leipzig) in the manner of the French Sun King. Since he lacked equal signs of power, he held himself harmless with all the more pompous titles of nobility, which also placed him in the immediate vicinity of God. It went something like this (and it would have made people laugh even then if such laughter had not easily cost them their heads): “By the Grace of God King in Poland, Grand Prince in Lithuania, Russia, Prussia, Masovia, Samogitia, Kyovia, Volhynia, Podolia, Podlachia, Lieffland, Hereditary Duke of Saxony, Jülich, Cleve, Berg, Engern and Westphalia, Archmarshall and Elector of the Holy Roman Empire, Landgrave in Thuringia, Margrave of Meissen, also Upper and Lower Lusatia, Burgrave of Magdeburg etc. pp.”

Did the people perhaps recognise God’s will precisely in the fact that he had the grace to make them the subjects of a theatrical regent who, with lavish exuberance, put them through many a hardship? For the spread of absolutism in Saxony was accompanied by an impoverishment of the lower classes. In Leipzig, the consequence was that shanty towns spread out in front of the city. How else, if not by the dubious benefits of their prince, should the people have known God’s will?

But come on, “Where there is danger, / That which saves also grows”. When Bach’s cantata sounded in Leipzig and urged the faithful to surrender to fate, perhaps not blindly, but full of trust in God, a certain Immanuel Kant was soon celebrating his second birthday in Königsberg. It was to be just under sixty years before his Grundlegung zur Metaphysik der Sitten would appear in 1785.

The ego as an autonomous subject that knew and dared to use its intellect was certainly not an invention of Kant. It found its congenial artistic expression in Bach’s Well-Tempered Clavier, where the rational order prevailed over the natural order. However, no one wrote with greater seriousness and in equally sharp and sometimes almost incomprehensible sentences to his contemporaries that there must now be an end to self-inflicted immaturity. Kant achieved the feat of not merely stating that man has free will, but went further by explaining that free will is precisely as such a proof of morality. Free will and will under moral laws are one and the same.

But now we could again ask somewhat maliciously: If it had already been difficult for people to recognise God’s will as such, how were they supposed to know where instinctuality and thus immorality ended and where free will and thus morality began? In any case, the difficult gift of this freedom seemed to cast people into a homelessness that they perhaps bore even worse than the bondage of bondage. So it could be a nasty historical joke when, at the end of 1804, the same year that Kant died, the French monarchy had long since been swept away, but Napoleon now crowned himself Emperor of the French in Notre-Dame Cathedral in Paris with his own hands and not by the grace of God – albeit in the presence of the Pope. He took the liberty of depriving his subjects of their freedom. History repeated itself as a farce, but the enlightened, self-liberated subject was suffering its bitterest insult.

Of course, it is at this historical turning point that things become really interesting. For between the disenchanted sky and the shaky precariat of newly won freedom, a gap has opened up for a third. What Freud at the beginning of the 20th century clothed in the half-revanchist, half-triumphant sounding sottise that the ego is not even master of its own house has long been part of the poets’ store of experience. In September 1806, when Friedrich Hölderlin was taken to the mental hospital in Tübingen against his will – yes, that too exists alongside free will or alongside God’s will – and held there for 230 days, he was subsequently placed in the care of the Tübingen carpenter Erich Zimmer and spent the last 36 years, and thus pretty much the second half of his life, in the tower room there. If visitors occasionally asked him for poems, he signed them with Scardanelli, Buonarotti or other names. The message was as confused as it was basically clear: where Hölderlin writes, someone else always writes as well. Now you will object with good reason that poor Hölderlin was not quite in his right mind at the time. That may be. But the gap between the absent God and the weakening ego was never more startling. Regardless of everything pathological, it manifested the condition of life of the enlightened ego, which now always had to consider its vulnerability and neediness. This applied all the more to artistic existence, which only found itself where it could tap into other, quieter sources beyond the powers of the intellect.

In order to penetrate such spheres, the young Arthur Rimbaud recommended in his Lettres du voyant of 1871 that all the senses should be allowed to roam freely. If you wanted to become a true poet, you had to be able to say, “It thinks me.” But that sounded too much like a corny joke to Rimbaud. He tried to put it more precisely and only now arrived at the simple formulation: “I is another.” Free will, my ass! There is always someone else writing.

So how was it with Maradona, and how was it with Bach? Let us return to the question posed at the beginning, whether Bach understood the same as his audience when he set the verse All only according to God’s will to music. We can be reasonably confident with regard to the listeners that they understood the cantata text in the vernacular theological sense. But what about Bach? What was he thinking about when he set the notes to the verses “O selger Christ, der allzeit seinen Willen / In Gottes Wille senken”? Did Bach know what he was doing? Did he too, as a composer, lower his will “at all times” into God’s will? Intuitively, we would claim: he insisted on obstinacy, free will, even if he would not have called it that, what he felt inwardly. But did someone else still co-write when he composed? Bach wouldn’t have said, “I is another.” But if Bach took his cantata text even halfway seriously, he must have been convinced in his innermost being that another was involved in his compositions, perhaps not called Scardanelli and not Buonarotti either. Would he have called him God? Who knows. “Lord, if you will…”: No less than nine times the cantata text repeats this formula. Doesn’t that sound like the composer’s sigh of despair, looking to heaven and waiting for inspiration?

But can one imagine Bach pausing, even doubting, pulling his hair out, crumpling up sheets of paper and throwing them into the wastepaper basket? Not really. You only have to look at his scores. The simple beauty of his notation never falters. Undeterred, the hand writes down what the head perhaps only really begins to hear with the typeface. Do we know this? Does this sound familiar? Do we know this head that is preceded by the hand? Do we know the head that knows how the ball should be hit, but doesn’t fly in fast enough to cross the line of flight exactly?

Couldn’t Bach have replied to inquisitorial questions about the seemingly magical art of his works: “Un poco con la cabeza de Bach y otro poco con la mano de Dios.” No, he wouldn’t have said it, because he didn’t know Spanish. But he wouldn’t have said it in German either, because it would have seemed blasphemous to him. But he would have known what his friend, for surely this poet of football would have been his friend, he would have known what Maradona meant: without the hand of God all poetry remains, without the hand of God even football remains unfinished.

And Bach would also have known what we are talking about here. In his house Bible there is this notation from his hand: “Bey einer andächtig Musig ist immer Gott mit seiner Gnaden Gegenwart.” Maradona would not have said it differently with regard to football. Whether it is musical art or ball art, God is always present in it.

Regardless of whether Bach calls it God’s grace, whether Maradona calls it God’s hand or whether we today call it something else altogether: art needs the other, it needs its Scardanelli, it always needs the completely different voice from the hidden, which is not that of the I in capital letters, in order to find the kairos of happy success and to advance into the unforeseeable.

This text has been translated with DeepL (www.deepl.com).