Liebster Gott, wenn werd ich sterben

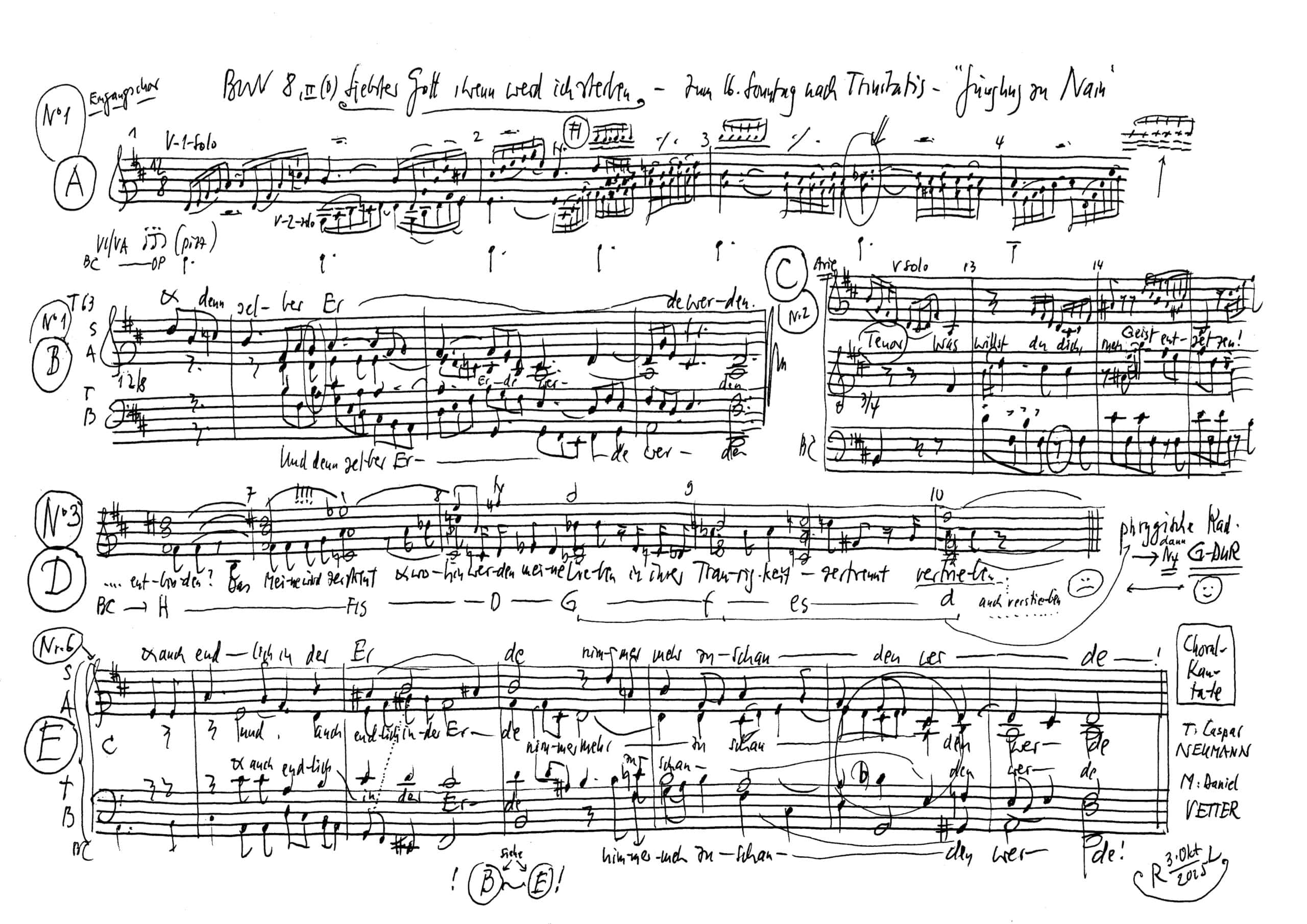

BWV 008 // For the Sixteenth Sunday after Trinity

(Dearest God, when will my death be) second version in D major, for soprano, alto, tenor and bass, vocal ensemble, transverse flute, oboe I+II, taille, violino concertato I+II, strings and basso continuo

Place of composition in the church year

Pericopes for Sunday

Pericopes are the biblical readings for each Sunday and feast day of the liturgical year, for which J. S. Bach composed cantatas. More information on pericopes. Further information on lectionaries.

Herr, Gott, du bist unsre Zuflucht für und für. Ehe denn die Berge wurden und die Erde und die Welt geschaffen wurden, bist du, Gott von Ewigkeit zu Ewigkeit, der du die Menschen lässest sterben und sprichst: «Kommt wieder, Menschenkinder!» Denn tausend Jahre sind vor dir wie der Tag, der gestern vergangen ist, und wie eine Nachtwache. – Lehre uns bedenken, dass wir sterben müssen, auf dass wir klug werden.

Darum bitte ich, dass ihr nicht müde werdet um meiner Trübsale willen, die ich für euch leide, welche euch eine Ehre sind. Derhalben beuge ich meine Kniee vor dem Vater unseres Herrn Jesu Christi, der der rechte Vater ist über alles, was da Kinder heisst im Himmel und auf Erden, dass er euch Kraft gebe nach dem Reichtum seiner Herrlichkeit, stark zu werden durch seinen Geist an dem inwendigen Menschen, dass Christus wohne durch den Glauben in euren Herzen und ihr durch die Liebe eingewurzelt und gegründet werdet, auf dass ihr begreifen möget mit allen Heiligen, welches da sei die Breite.

Choir

Soprano

Stephanie Pfeffer, Jennifer Ribeiro Rudin, Noëmi Sohn Nad, Mirjam Wernli, Ulla Westvik

Alto

Anne Bierwirth, Antonia Frey, Laura Kull, Francisca Näf, Simon Savoy

Tenor

Marcel Fässler, Clemens Flämig, Tobias Mäthger, Tiago Oliveira

Bass

Fabrice Hayoz, Johannes Hill, Grégoire May, Peter Strömberg, William Wood

Orchestra

Conductor

Rudolf Lutz

Violin

Éva Borhi, Péter Barczi, Christine Baumann, Judith von der Goltz, Petra Melicharek, Ildikó Sajgó, Lenka Torgersen, Aliza Vicente

Viola

Martina Bischof, Lucile Chionchini, Matthias Jäggi

Violoncello

Maya Amrein, Daniel Rosin

Violone

Guisella Massa

Transverse flute

Daniela Lieb

Oboe

Philipp Wagner, Katharina Arfken

Bassoon

Susann Landert

Taille

Josefa Winterfeld

Harpsichord

Thomas Leininger

Organ

Nicola Cumer

Musical director & conductor

Rudolf Lutz

Workshop

Participants

Rudolf Lutz, Pfr. Niklaus Peter

Reflective lecture

Speaker

Anna-Magdalena Elsner

Recording & editing

Recording date

24/10/2025

Recording location

Trogen AR (Switzerland) // Evang. Kirche

Sound engineer

Stefan Ritzenthaler

Producer

Meinrad Keel

Executive producer

Johannes Widmer

Production

GALLUS MEDIA AG, Schweiz

Producer

J.S. Bach-Stiftung, St. Gallen, Schweiz

Libretto

1. Choral

Liebster Gott, wenn werd ich sterben?

Meine Zeit läuft immer hin,

und des alten Adams Erben,

unter denen ich auch bin,

haben dies zum Vaterteil,

daß sie eine kleine Weil

arm und elend sein auf Erden

und denn selber Erde werden.

2. Arie — Tenor

Was willst du dich, mein Geist, entsetzen,

wenn meine letzte Stunde schlägt?

Mein Leib neigt täglich sich zur Erden,

und da muß seine Ruhstatt werden,

wohin man soviel tausend trägt.

3. Rezitativ — Alt

Zwar fühlt mein schwaches Herz

Furcht, Sorge, Schmerz:

Wo wird mein Leib die Ruhe finden?

Wer wird die Seele doch

vom aufgelegten Sündenjoch

befreien und entbinden?

Das Meine wird zerstreut,

und wohin werden meine Lieben

in ihrer Traurigkeit

zertrennt, vertrieben?

4. Arie — Bass

Doch weichet, ihr tollen, vergeblichen Sorgen!

Mich rufet mein Jesus, wer sollte nicht gehn?

Nichts, was mir gefällt,

besitzet die Welt.

Erscheine mir, seliger, fröhlicher Morgen,

verkläret und herrlich vor Jesu zu stehn.

5. Rezitativ — Sopran

Behalte nur, o Welt, das Meine!

Du nimmst ja selbst mein Fleisch und mein Gebeine;

so nimm auch meine Armut hin!

Genug, daß mir aus Gottes Überfluß

das höchste Gut noch werden muß;

genug, daß ich dort reich und selig bin.

Was aber ist von mir zu erben,

als meines Gottes Vatertreu?

Die wird ja alle Morgen neu

und kann nicht sterben.

6. Choral

Herrscher über Tod und Leben,

mach einmal mein Ende gut,

lehre mich den Geist aufgeben

mit recht wohlgefaßtem Mut!

Hilf, daß ich ein ehrlich Grab

neben frommen Christen hab

und auch endlich in der Erde

nimmermehr zuschanden werde!

This text has been translated with DeepL (www.deepl.com).

Anna Magdalena Elsner

Ladies and gentlemen,

When I was invited to speak about the cantata we have just heard, I was truly delighted. And to be perfectly honest, this delight did not stem primarily from the fact that today, in a somewhat different way than in my everyday life, I have the opportunity to deal with death and dying. Rather, my delight was a very personal one: my parents gave me my first name – Anna Magdalena – out of their love for Bach. The hopes that parents place in a name do not always come true. In my case, however, it did: the name I share with Bach’s second wife not only gave me a special access to his music, but also drew my attention to the woman who stood by his side as a musician, but probably also in his shadow. When I listen to this cantata, however, she steps into the light for me.

When the cantata was written, Bach had only recently married his second wife. Soon afterwards, the family was struck by a series of deaths: many of their children died, and Anna Magdalena had to bury seven of the thirteen children she bore during her lifetime – a fate whose severity we can hardly imagine. In such a life, permeated by death and grief, the harshness of earthly existence takes on an oppressive reality.

But it is not only the motif of death, but also that of survival – the conviction that there is such a thing and the serenity with which the hardship of life can be accepted – that for me is inseparably linked to Anna Magdalena. Not only did she outlive her husband and many of her children, but in her role as copyist of his music, she contributed significantly to Bach’s music surviving his death. In a sense, her quiet work therefore extends into our present day – as the invisible hand that made her husband’s posthumous fame and the continued existence of his music possible in the first place. As a translator, she became part of his music and thus also part of a creativity that was closely linked to death.

Between cantata and capsule

And since we know relatively little for certain about the lady Kapellmeister, we can imagine a great deal. I imagine what might have gone through her mind as she copied a cantata about dying. Perhaps, as a singer, she also sang the cantata herself. This possible participation connects her own life story with that of the work – and thus makes tangible a fundamental question that is already inherent in the creation of the cantata: How can one continue to live after a loss – not just any loss, but the death of a child or even one’s own children? This experience of grief leads to the intellectual leap from the death of another to the death of the self, to the question of one’s own end. In the character of Anna Magdalena Bach, this path – from the other to the self – is led out of abstraction and condensed into an elementary, almost childlike and at the same time shockingly existential question: When will I die? Yes, perhaps even, when can I finally die?

For many people in the 21st century, the belief in an afterlife that we encounter in the cantata may seem strange, even inaccessible. But in fact, this unfolds here less as a certainty than as a web of questions: When will my time come? What will I think about then? Where will I be buried – and what will become of the people I leave behind? Thus, we encounter not only an unshakeable faith, but also a tentative struggle with the unknown.

I cannot help but hear these questions in our current medical context, where the question of when has inevitably entered the horizon of patient autonomy. Today, many countries, including many of our neighbours, are negotiating the legalisation of euthanasia; Switzerland is the oldest country that does not prohibit it under certain conditions. In Canada, which has perhaps the most liberal euthanasia regime in the world, one in twenty people died by euthanasia in 2023; in the province of Québec, the figure was even higher. This raises the question of what can be considered a good end in times of radical individualisation. These debates cover a lot of ground: the role of medicine and society, norms, autonomy and dignity, concepts that ultimately converge on one point: the hour of one’s own death. It is perhaps the most pressing question that terminally ill people ask doctors and carers: when will I die? How long do I have left? Medicine can provide increasingly precise answers to this question. But the question is changing: “When will I die?” is becoming “When, where and how do I want to die?” – or even “When, where and how should I die?” In this shift, which culminates in the promise of self-determined death, the question of “when” no longer appears as a mystery, but as an option – an expression of freedom of choice. This idea takes shape in the shiny Sarco suicide capsule in the Schaffhausen forest: a symbol of secularised salvation, in which medicine, which in many places in the twentieth century assumed control over dying, is now deliberately excluded. Dying at the touch of a button. In a place where you no longer need anyone else to die.

In the face of one’s own death

But I would like to take a step back – to the very possibility of being able to ask the question: When will I die? Viewed from the cantata, this step back also leads forward: to the beginning of the twentieth century, to an essay that reversed the question of when we will die – or, in other words, fundamentally doubts that we can even think about our own death. In his short essay “Contemporary Thoughts on War and Death” (1915) – a text that has unfortunately regained disturbing relevance in recent years – Sigmund Freud writes:

“Our own death is also unimaginable, and no matter how often we try to imagine it, we notice that we actually remain spectators. This led the psychoanalytic school to venture the statement: basically, no one believes in their own death or, which amounts to the same thing, in our unconscious, each of us is convinced of our immortality.”

Rationally, we may be able to grasp the certainty of our death, but in a deeper sense it remains inconceivable to us. Life itself requires the constant repression of this certainty, since in our unconscious mind death always affects “only others”. With this insight, Freud joins a philosophical tradition that points to the impossibility of truly conceiving of one’s own end. Today, here, this perspective may seem plausible to us, even beyond all abstraction: Even without Freud’s repression, it remains clear that the conditions of dying in Western societies have changed profoundly: not only do we live considerably longer on average, but dying itself – in Switzerland, the majority of people die in retirement and nursing homes or in hospitals – has largely been shifted from the everyday world to institutional spaces.

The situation was very different in 18th-century Leipzig, where death was closer, more visible and usually more painful – without antibiotics, morphine or palliative care. The question of the hour of death was not merely an intellectual concern, but an immediate experience. However, this does not mean that death is no longer a reality today, or that it has become taboo – on the contrary: narratives of death in literature and film are booming across languages and cultures. They deal with terminal illnesses, loneliness and the use of euthanasia, and seem to have become a new ritual of death themselves. A medicalised or even self-determined death is not necessarily an easier one, but it is certainly a very different one.

What artistic and often religious testimonies from past centuries and contemporary debates about dying have in common, however, is that they remind us that the certainty of our mortality remains. Regardless of our unconscious fantasies of eternal life, Silicon Valley’s immortality projects, or the fact that death rarely occurs in our homes anymore, dying remains our lowest common denominator, whether public or hidden, self-determined or surrendered. Death is never really far away.

And often these artistic explorations – in a memory, a sentence, an image, a gesture – even make one’s own death inescapable for a moment. I had a deeply religious grandmother. One of my most vivid childhood memories of her is a long train journey from Zurich to the North Sea, during which she taught me to pray the rosary. I can still see us in the compartment: the steady movement of her lips, the beads between her fingers, the murmur of prayers mingling with the clatter of the wheels. I remember the boredom that spread through the litany of the slowly advancing train, my doubts as to whether I really believed what I was repeating, and the quiet shame when other passengers opened the door, paused briefly and then – slightly alienated by the sight of us praying – moved on. But when you repeat “now and at the hour of our death” a hundred times, you give that hour its own reality, initially only linguistic, but then, through repetition, through breath, through the sound of the words, it becomes physical – death inscribes itself into life, syllable by syllable. And as I continued to murmur the words, I began – almost imperceptibly – to imagine that hour of death: my own death – without pain, of course, the loud crying of those who would stand around my bed and miss me (tears welled up in my eyes), the wooden coffin in which I would wear my most beautiful dress, the one my parents had bought me on a trip to Paris, and above all, the important question of who I would leave my real gold necklace to.

Born to the earth

Today, this childishly pious painting of my blissful hour of death is connected for me with a completely different, radically sobering image – with Samuel Beckett, who in Waiting for Godot shows humans as beings who are born “astride the grave”. And when Vladimir, one of the two waiting characters in Beckett’s play, says: “From below – from the pit – the gravedigger hesitantly applies his forceps,” this image becomes almost unbearably vivid and the paradox of human existence mercilessly apparent: birth and death merge, beginning and end are barely distinguishable. Beckett depicts the total disenchantment of my blissful hour of death.

The force of this image makes me shudder again and again. And yet it reveals – as it does in the present and in the hour of our death – the same truth: life and death belong together. At the same time, Beckett reverses an ancient idea: that a good death can perhaps be part of a good life. This idea dates back to antiquity and is continued in the medieval pictorial and textual tradition of the ars moriendi – the ‘art of dying’, which taught in texts and woodcuts that inner attitude and preparation are the keys to a good death.

When listening to the cantata, however, Beckett’s image stays with me precisely because the desire for a happy ending is intertwined with something completely different: physicality and materiality. Earth and grave play a central role here: being on earth, becoming earth – the image of the body slowly leaning towards the earth. Where Freud speaks of psychological repression, the human body pushes itself to the fore here: susceptible, fragile, vulnerable, it does not allow repression because it pushes itself towards the earth from birth. When will I die is not a question that we can break down into its individual parts or ask in a vacuum; it is not an abstract consideration, because its starting point is always a living and therefore already dying body.

In her moving book Easy Beauty: Views on My Disability, American author Chloé Cooper Jones describes her life with a rare physical disability – being born with an incomplete spine. She writes about pain, about the visibility of her different body and how this body, which leans towards the earth, forces her to move differently through the world: slower, deeper, more stooped, with more consideration. For a long time, she felt this was a defeat and tried to hide her body. But last year, she appeared in a dance performance on New York’s High Line with the meaningful title Die No Die. In it, she dances with her body, especially in a seemingly simple exercise that the choreographer had her do over and over again: laying her head and her whole body on the ground. Resistance, letting go, surrender – and finally: security, oneness with the earth, humility. For me, this gesture of laying down the body is an image of fitting into human existence; it combines imposition and courage, giving rise to an awareness of limitations.

Perhaps this is precisely what resonates in the cantata – and touches us: the movement of the body bending towards the earth, in which knowledge and uncertainty merge. For me, Anna Magdalena Bach also appears in this gesture: a figure between life and death, whose hands preserved Bach’s music and whose voice perhaps carried it. The fact that we know so little about her is not a loss, but part of her presence – a void that leaves room for our own imagination. Thus Anna Magdalena becomes a silent witness to death and survival, and the cantata an echo of an in-between – a moment in which life bends towards the earth, searching, questioning, groping. Thank you.