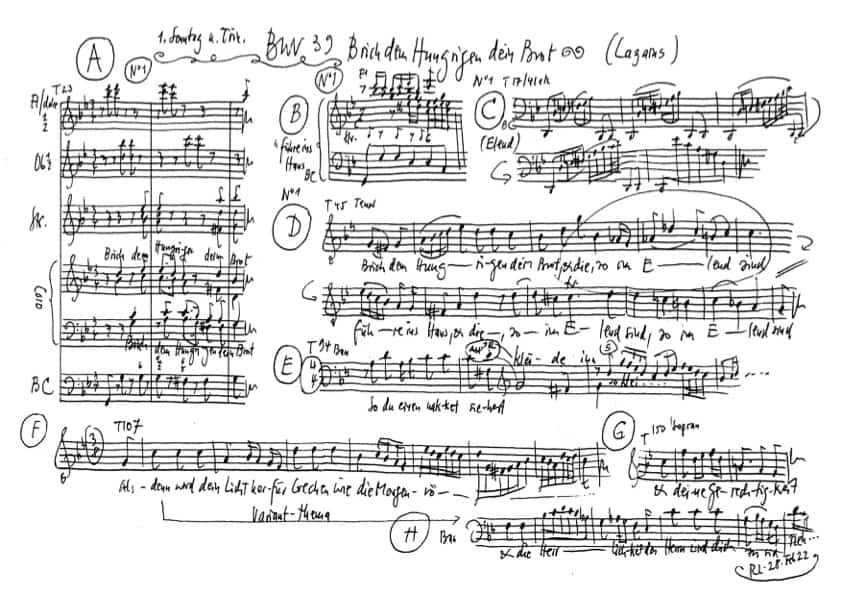

Brich dem Hungrigen dein Brot

BWV 039 // For the First Sunday after Trinity

(Break with hungry men thy bread) for soprano, alto und bass, vocal ensemble, oboe I+II, recorder I+II, strings and basso continuo

Would you like to enjoy our videos ad-free? Subscribe to YouTube Premium now...

Workshop

Reflective lecture

Choir

Soprano

Keiko Enomoto, Cornelia Fahrion, Julia Schiwowa, Simone Schwark, Susanne Seitter

Alto

Laura Binggeli, Antonia Frey, Francisca Näf, Lea Pfister-Scherer, Lisa Weiss

Tenor

Rodrigo Carreto, Tiago Oliveira, Sören Richter, Nicolas Savoy

Bass

Fabrice Hayoz, Serafin Heusser, Grégoire May, Daniel Pérez, Philippe Rayot

Orchestra

Conductor

Rudolf Lutz

Violin

Renate Steinmann, Monika Baer, Patricia Do, Elisabeth Kohler, Olivia Schenkel, Salome Zimmermann

Viola

Susanna Hefti, Claire Foltzer, Matthias Jäggi

Violoncello

Martin Zeller, Hristo Kouzmanov

Violone

Markus Bernhard

Recorder/Flute

Yukiko Yaita, Kiichi Suganuma

Oboe

Andreas Helm, Philipp Wagner

Bassoon

Susann Landert

Harpsichord

Thomas Leininger

Organ

Nicola Cumer

Musical director & conductor

Rudolf Lutz

Workshop

Participants

Rudolf Lutz, Pfr. Niklaus Peter

Reflective lecture

Speaker

Werner van Gent

Recording & editing

Recording date

18/03/2022

Recording location

Trogen AR (Schweiz) // Evangelische Kirche

Sound engineer

Stefan Ritzenthaler

Producer

Meinrad Keel

Executive producer

Johannes Widmer

Production

GALLUS MEDIA AG, Schweiz

Producer

J.S. Bach-Stiftung, St. Gallen, Schweiz

Librettist

First performance

23 June 1726, Leipzig

Text

Isaiah 58:7–8 (movement 1); Letter to the Hebrews 13, 16 (movement 4); David Denicke (movement 7); unknown poet/texts printed in Meiningen 1719 and Rudolstadt 1726 (movements 2–3), Christoph Birkmann (movements 5–6)

In-depth analysis

Cantata BWV 39 was composed for the First Sunday after Trinity and marks the beginning of Bach’s fourth annual cycle. Like other cantatas in this group, the work is set in two parts that open with dictums from the Old and New Testament respectively, an approach typical in the cantatas of Bach’s Meiningen cousin Johann Ludwig Bach. Already the two assigned readings for the Sunday – Godly love as a model for Christian charity in the Epistle (1 John, 4) and the parable of the rich man and the beggar Lazarus (Luke 16) – reinforce the core message of practising compassion.

The introductory chorus opens in a tranquil but impressive style, with individual pairs of quavers being passed among the strings and oboes as well as the recorders (which almost always feature when Bach wishes to express pastoral safety or trusting, childlike love) in a motif that represents the breaking and sharing of bread. The paired vocal parts then follow this gesture, which intensifies first with the accelerated continuo motif on “und die, so im Elend sind, führe ins Haus” (and those who in want are found, take in thy house). The repetition of the first two lines then takes the shape of a broad-scale fugue with expressive sighs on the word “Elend” (want), ere a reprise with entries in close succession rounds off this first large section. Bach sets the next thoughts as an exchange between a precentor (“So du einen nackend siehest” – If thou dost a man see naked) and a tutti section (“So kleide ihn!” – then cover him) that transitions to a motet-like declamation (“und entzeuch dich nicht von deinem Fleisch” – and withdraw thyself not from thy flesh). The conclusion comprises a canon-like series of two thematically related fugues set to the lines opening with “alsdenn wird dein Licht herfürbrechen” (And then shall thy light through all break forth) and “und die Herrlichkeit des Herrn” (and the majesty of the Lord God), complete with an elegant figuration on “und deine Gerechtigkeit” (and thine own righteousness). In this final section, the dance-like buoyancy and masterful text-setting meld organically into an artistic form that comes to a surprisingly radiant close.

The opulent bass recitative derives sufficient energy from this opening to explore the gift of God’s “Überfluss” (abundance): everything we possess has been given to us only as a “Probestein” (touchstone) to prove our neighbourly love. We have only the “Genuss” (use) and not ownership of God’s gifts; and God, too, has no desire to earn interest on them – already then an ill-reputed practice. Rather, God wishes to provide us with a means to show compassion, the warmth of which is extolled in the closing cantilena.

The following alto aria opens in a brighter F major key and a lilting 3⁄8-metre that lends the obbligato duo for oboe and violin a pleasing flow. In this delicate soundscape, the promise of faintly resembling the creator through the act of giving becomes attainable – something that the librettist, in good Lutheran fashion, interprets not as a reason for justification before God, but as a “Vorschmack” (foretaste) of eternal salvation: we gain nothing through the act of giving; rather, it reveals the blessing that is already upon us and plants the seed of future heavenly bliss.

After the sermon, which is held following the aria, the second part of the work opens with an equally admonishing and touching arioso whose introductory continuo statement is taken up by the bass soloist as the vox Christi: “Wohlzutun und mitzuteilen, vergesset nicht, denn solche Opfer gefallen Gott wohl” (To do good and share your blessings forget ye not; for these are offerings well-pleasing to God). Indeed, such an earnest invitation to take part in a lifelong offertory is nigh impossible to resist.

Accordingly, the following soprano aria functions as a particularly charming surrender to an inescapable commandment. The high register, catchy 6⁄8-metre and, once again, the obbligato recorder emphasise the setting’s insightful spirit of commitment: “Höchster, was ich habe, ist nur deine Gabe” (Highest, my possessions, are but what thou givest). It is an affirmation that requires neither artifice nor length, but captivates through its simple honesty.

This liberated acceptance of one’s own limits is underscored in the alto recitative, whose string accompaniment lends the setting a subdued, ceremonious character: humans are worthy of only what God gives them in life – but each of us can bear this with dignity and share our gifts in solidarity. The closing chorale then expresses this sentiment in the wise words of David Denicke, the Hannover consistorial councillor, providing an effective summary that in Bach’s evocative cantional setting takes on traits of a veritable beatitude. At the same time, the doubling woodwinds permeate the soprano voice like the warm inspiration of good deeds.

Libretto

1. Chor

«Brich dem Hungrigen dein Brot, und die, so im Elend sind, führe ins Haus! So du einen nacket siehest, so kleide ihn und entzeuch dich nicht von deinem Fleisch. Alsdenn wird dein Licht herfürbrechen wie die Morgenröte, und deine Besserung wird schnell wachsen, und deine Gerechtigkeit wird für dir hergehen, und die Herrlichkeit des Herrn wird dich zu sich nehmen.»

2. Rezitativ — Bass

Der reiche Gott wirft seinen Überfluß

auf uns, die wir ohn ihn auch nicht den Odem haben.

Sein ist es, was wir sind; er gibt nur den Genuß,

doch nicht, daß uns allein

nur seine Schätze laben.

Sie sind der Probestein,

wodurch er macht bekannt,

daß er der Armut auch die Notdurft ausgespendet,

als er mit milder Hand,

was jener nötig ist, uns reichlich zugewendet.

Wir sollen ihm für sein gelehntes Gut

die Zinse nicht in seine Scheuren bringen;

Barmherzigkeit, die auf dem Nächsten ruht,

kann mehr als alle Gab ihm an das Herze dringen.

3. Arie — Alt

Seinem Schöpfer noch auf Erden

nur im Schatten ähnlich werden,

ist im Vorschmack selig sein.

Sein Erbarmen nachzuahmen,

streuet hier des Segens Samen,

den wir dorten bringen ein.

4. Arie — Bass

«Wohlzutun und mitzuteilen vergesset nicht; denn solche Opfer gefallen Gott wohl.»

5. Arie — Sopran

Höchster, was ich habe,

ist nur deine Gabe.

Wenn vor deinem Angesicht

ich schon mit dem meinen

dankbar wollt erscheinen,

willt du doch kein Opfer nicht.

6. Rezitativ — Alt

Wie soll ich dir, o Herr! denn sattsamlich vergelten,

was du an Leib und Seel mir hast zugut getan?

Ja, was ich noch empfang, und solches gar nicht selten,

weil ich mich jede Stund noch deiner rühmen kann?

Ich hab nichts als den Geist, dir eigen zu ergeben,

dem Nächsten die Begierd, daß ich ihm dienstbar werd,

der Armut, was du mir gegönnt in diesem Leben,

und, wenn es dir gefällt, den schwachen Leib der Erd.

Ich bringe, was ich kann, Herr, laß es dir behagen,

daß ich, was du versprichst, auch einst davon mög tragen.

7. Choral

Selig sind, die aus Erbarmen

sich annehmen fremder Not,

sind mitleidig mit den Armen,

bitten treulich für sie Gott.

Die behülflich sind mit Rat,

auch, wo möglich, mit der Tat,

werden wieder Hülf empfangen

und Barmherzigkeit erlangen.

Werner van Gent

The cantata that has just been performed so beautifully and that we will hear again in a moment, it is almost 296 years old, the opening text from Isaiah even much, much older – and yet: this cantata could not have been more topical today, a cantata that in essence is nothing other than an urgent call for solidarity with the needy, the weaker.

Solidarity is exactly what we are experiencing these days. As shocking as the enormous suffering in Ukraine since 24 February is, as incomprehensible as the actions of the Russian despot may be, when we see the force with which the willingness to help is unfolding in Europe, it is heart-warming and impressive – without ifs and buts.

Our government, the Federal Council, which just a short while ago had fugitives from Afghanistan expelled on the basis of legal considerations with icy harshness, made a U-turn within a few days in favour of a humanitarian commitment that actually deserves the name. That is remarkable.

What is different today in the Ukraine war? What is the effect of this unprecedented willingness to help? The Afghan writer Emran Feroz, whom I hold in high esteem, asked the anxious question of whether the colour of the eyes of the refugees might play a role.

I would like to hope that this is not the case with the vast majority in our country. If we are breaking our bread for the needy in Ukraine, there is obviously something else at play.

If you look at the opinion polls, an astonishingly large part of Europe’s population is now willing to do without Russian gas and oil even if this would lead to major shortages in our energy supply.

We all seem to feel seriously threatened by a despotic attack on our peace, on our system, on our social order.

It now seems to many that we are in a war of systems, a war of despotism against democracy. Many still try to reduce this struggle to one person in the Kremlin – it would be nice, because then all problems would be solved if this person disappeared. But that is all too easy. An international alliance of despotism is in the making. Mohammed bin Salman, Putin and Xi Jinping are united by a deep dislike of our social order. They are even in the process of replacing the dollar as the reserve currency for oil sales with the Chinese currency. With their own banks and without SWIFT, without having to consider the principles of the West. They want us as customers, but they should keep their mouths shut. Do we want to accept that?

How should we respond to this war of systems? Everywhere, in Germany, in the USA, even in Switzerland, there are calls to increase defence spending. NATO, which has just staged a horrific debacle in the Hindu Kush, is now supposed to save the Western democracies, while it has to remain inactive in Ukraine for obvious reasons. I am very sceptical about this.

Of course, when there is a danger of fire, it is good to have a trained fire brigade at hand. But I have experienced too many wars to believe that the military will be able to solve the conflicts – Afghanistan, Iraq, Syria. The best army is still the one that is never deployed because people respect it. From this point of view, the military cards must never land on the table.

But right now, the cards are unsparingly on the table – and they are not good cards for the West.

If I may briefly use the comparison to the danger of fire: at least as important as a well-practised fire brigade is good prevention, good fire protection regulations. Transferred to the international arena, this means that an effective security architecture is needed, an architecture that guarantees security for all states involved.

Unfortunately, however, the security edifice that was created after World War II and expanded during the Cold War has been systematically weakened in recent years, even maliciously deconstructed by Trump, Putin and others; agreements on arms control, on mutual control flights, international structures such as the OSCE, all this and much more has been allowed to expire. Today we are faced with a shambles.

And military deterrence? Right now it only works in one direction, as we have painfully learned in Ukraine.

Henry Kissinger, by no means a pacifist, but a hard-nosed politician who thinks in global categories, predicted quite accurately in a report in the Herald Tribune in 2014 what would go wrong if the complex political situation in Ukraine and the Kremlin’s objectives were not properly assessed. His warnings went unheeded at the time. In the end, things turned out exactly as he had predicted.

The policy of appeasement, the blind belief that despots will come to their senses through business – how often do we have to learn that this does not work? It didn’t work for Hitler, it doesn’t work for Erdogan, it doesn’t work for Mohammed bin Salman and it certainly doesn’t work for Xi Jinping.

I just can’t understand how people throw themselves into the fray so that more armament is absolutely necessary, who are prepared to pay between 2 and 3% of GDP for it, but who shy away from effective sanctions because, in the case of Russia, they could cost another 3-4% of GDP.

Sanctions and embargoes are expensive, and they only work if they have multinational support. However, if such measures are applied consistently, they become a highly effective deterrent, highly effective against further attacks that are sure to come. We can see how the always smugly smiling Xi Jinping has just become a little nervous because the golden deal along his new Silk Road is in danger.

This is the only leverage we have in the global war of systems. But economic deterrence must be at least as credible as nuclear deterrence. The half-hearted sanctions of the past were counterproductive, they showed the despots all over the world: “Do what you want – we just want to carry on our business.”

Often they say: “If we don’t deliver, our competitors will” – this is true and only proves how important it is to support international sanctions broadly. Again, effective sanctions cost money, a lot of money, but not nearly as much money as the havoc being wreaked in Ukraine right now. And: We have a well-developed insurance industry that could at least partially cushion the risks associated with sanctions, as is already working excellently with ERGs or Hermes guarantees.

The great advantage of economic leverage: They can be used in a targeted manner at the negotiating table. For one thing should be clear: No matter how much this systemic war comes to a head, in the end we will have to negotiate again.

The alternative would be the chaos of a global repetition of the Thirty Years’ War.

Incidentally, the European Thirty Years’ War in the 17th century is a good example of how, in the end, it is only diplomacy that can end conflicts.

Negotiations lasted for five years until the Peace of Westphalia on 24 October 1648 put an end to the slaughter in Central Europe and, incidentally, to the Netherlands’ 80-year war of independence against the Spanish.

A third of the people living in Central Europe had not survived the murder and killing and the accompanying epidemics. The continent lay in ruins. Yet peace was made.

One thing should be clear to us here and now: without this peace, we would hardly be able to hear the wonderful music of Johann Sebastian Bach today. For it was these treaties that gave Central and Western Europe an economic upswing. In Saxony, we speak of the “Age of Augustus”, in which Elector Augustus allowed culture to blossom – the Baroque Age experienced one climax after another.

Unfortunately, peace at that time did not mean prosperity and justice for all. On the contrary.

In Saxony, even 70 years after the conclusion of peace, i.e. around the time Cantata 39 was written, about half the people lived in the extreme precariat. Women, by the way, were particularly affected, being more than three times as hard hit by poverty as men: maids who had been impregnated by the landlords and then thrown out onto the street, widows, single mothers. The only way out for many of these women was either beggary or prostitution.

The then prevailing class system with guilds and a corrupt aristocracy blocked the social advancement of the individual. The promise of the Enlightenment was not fulfilled, the system was dysfunctional. In this sense, the cry “Break bread for the hungry” was also an expression of the realisation that one was living on a social volcano, a volcano that was to erupt three generations later in the Paris basin.

Much of what has improved since then is due to precisely this insight, namely the insight that the “breaking of bread” is not only to be understood as a sign of mercy, but also as a prerequisite for the survival of a social order.

In the cantata, the reward for this still comes from God. In our secularised world, the reward may be experienced much more directly, provided that in the extremely dangerous war of systems, we are willing for once to subordinate our “business as usual” to the survival of our social order. I ask you to listen to Cantata 39 again from precisely this point of view.

This text has been translated with DeepL (www.deepl.com).