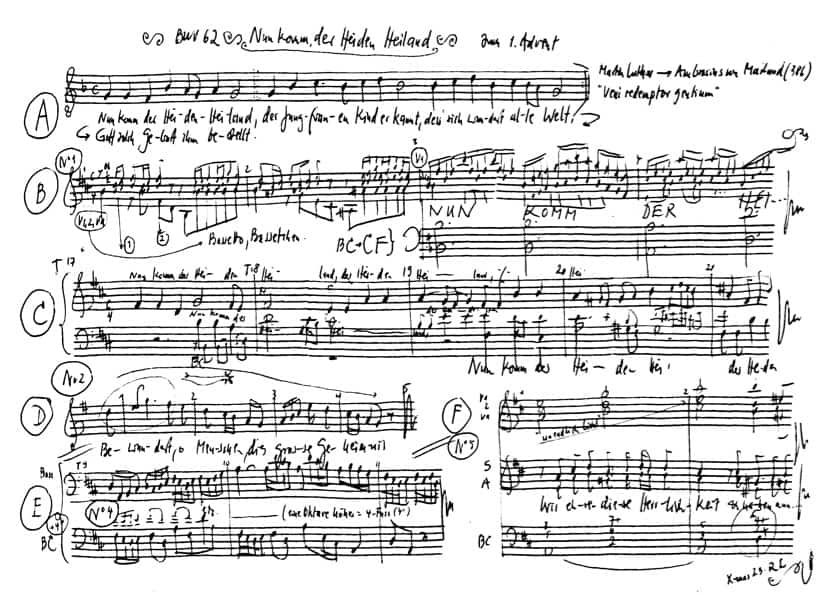

Nun komm, der Heiden Heiland

BWV 062 // For the First Sunday in Advent

(Now come, the gentiles’ Saviour) for soprano, alto, tenor and bass, vocal ensemble, horn, oboe I+II, strings and basso continuo

Would you like to enjoy our videos ad-free? Subscribe to YouTube Premium now...

Workshop

Reflective lecture

Choir

Soprano

Lia Andres, Cornelia Fahrion, Noëmi Tran-Rediger, Alexa Vogel, Mirjam Wernli

Alto

Antonia Frey, Francisca Näf, Jan Thomer, Sarah Widmer

Tenor

Zacharie Fogal, Joël Morand, Sören Richter, Nicolas Savoy

Bass

Jean-Christophe Groffe, Grégoire May, Daniel Pérez, Philippe Rayot, Tobias Wicky

Orchestra

Conductor

Rudolf Lutz

Violin

Éva Borhi, Petra Melicharek, Ildikó Sajgó, Lenka Torgersen, Dorothee Mühleisen, Judith von der Goltz

Viola

Martina Bischof, Sonoko Asabuki, Matthias Jäggi

Violoncello

Maya Amrein, Daniel Rosin

Violone

Markus Bernhard

Oboe

Philipp Wagner, Ingo Müller

Bassoon

Susann Landert

Horn

Thomas Friedlaender

Harpsichord

Thomas Leininger

Organ

Nicola Cumer

Musical director & conductor

Rudolf Lutz

Workshop

Participants

Rudolf Lutz, Pfr. Niklaus Peter

Reflective lecture

Speaker

Dominik Wunderlin

Recording & editing

Recording date

15/12/2023

Recording location

Teufen AR (Switzerland) // Evang. Kirche

Sound engineer

Stefan Ritzenthaler

Producer

Meinrad Keel

Executive producer

Johannes Widmer

Production

GALLUS MEDIA AG, Schweiz

Producer

J.S. Bach-Stiftung, St. Gallen, Schweiz

Librettist

First performance

3 December 1724, Leipzig

Text

Martin Luther (movements 1, 6); unknown source (movements 2–5)

In-depth analysis

Every church cantata by Bach is a unique masterpiece, and this lends the few instances where he set the same opening cantata verse in two different ways a particular appeal, as these works represent a new musical approach and provide insight into his compositional development.

An excellent case in point is the cantata “Nun komm der Heiden Heiland” (Now come, the gentiles’ Saviour) BWV 62, composed for the First Sunday in Advent in 1724. Whereas its sister cantata BWV 61 – composed in 1714 as one of Bach’s earliest Weimar cantatas – is an ingenious union of Luther’s powerful Advent hymn with the form of a French overture, the opening chorus of BWV 62 forms part of the 1724/25 chorale cantata cycle and is shaped by its compositional models. Indeed, the setting is structured as a concerto for strings, oboes and basso continuo, providing a framework for presenting the four chorale lines. Distinctive features such as the omission of the bass at the beginning of the movement and the instrumental pre-imitations of the chorale lines, not to mention the horn’s reinforcement of the soprano melody, demonstrate Bach’s respect for Luther’s chorale, which is based on a Gregorian hymn. Here, the rhythmic urgency and insistent note repetitions embody waiting for the saviour, who will miraculously rescue the undeserving world from the brink of a bottomless abyss.

Accordingly, the dancelike tenor aria, accompanied by a radiant orchestral tutti setting, invites listeners to marvel at the mystery of Jesus’ birth. When the vocal soloist praises “der höchste Beherrscher” (the highest of rulers) in rapturous coloraturas for having appeared on earth, the subtle shifts of register between delicate strings and full-sounding oboes evokes a type of tender smile – far removed from a cry of triumph – that is familiar to parents of all times upon first seeing their new-born child.

The brief but weighty bass recitative then clarifies that the soon-to-be-born baby Jesus is none other than God’s only begotten son. Descending from «Gottes Herrlichkeit und Thron» (God’s great majesty and throne) to fulfil the hopes of the people and the prophecies of the Old Testament, his redeeming arrival provides for a heaven-sent radiance and blessing.

This “man of Judah”, whose origins can be traced back to the Book of Genesis, is portrayed in the following aria as a victorious hero, thus foreshadowing Jesus’ journey beyond the events of Christmas. Here, the accompaniment of unison strings and basso continuo underscores his incomparable deeds of love, with the shimmering triple octaves evoking the human-divine duality of Jesus’ life as well as his place in the Trinity. By contrast, the soloist’s down-to-earth bass register and ascending, circling bravura gestures convey a combativeness and energy that must surely prevail and that will fortify the spirits of the notoriously weak “children of men”.

The notion that this “Herrlichkeit” (majesty) remains an unfathomable happening that mortals may contemplate with only with the utmost humility is captured by Bach in a recitative duo of peerless tenderness. Here, the soprano and alto approach the manger in reverent, whispering tones, accompanied by piano strings evoking the infinite light of eternity that penetrates all darkness of the world.

Following the modern transcriptions of the inner verses of the chorale, Luther’s original text of 1524 returns to the fore in the simple four-part closing chorale. With its ancient language and archaic melody, the setting celebrates the infinite praise of the triune God of creation.

Libretto

1. Chor

Nun komm, der Heiden Heiland,

der Jungfrauen Kind erkannt,

des sich wundert alle Welt,

Gott solch Geburt ihm bestellt.

2. Arie — Tenor

Bewundert, o Menschen, dies große Geheimnis:

der höchste Beherrscher erscheinet der Welt.

Hier werden die Schätze des Himmels entdecket,

hier wird uns ein göttliches Manna bestellt,

o Wunder! die Keuschheit wird gar nicht beflecket.

3. Rezitativ — Bass

So geht aus Gottes Herrlichkeit und Thron

sein eingeborner Sohn.

Der Held aus Juda bricht herein,

den Weg mit Freudigkeit zu laufen

und uns Gefallne zu erkaufen.

O heller Glanz, o wunderbarer Segensschein!

4. Arie — Bass

Streite, siege, starker Held!

Streite, siege, starker Held,

sei vor uns im Fleische kräftig!

Sei geschäftig,

das Vermögen in uns Schwachen

stark zu machen!

5. Rezitativ — Duett: Sopran; Alt

Wir ehren diese Herrlichkeit

und nahen nun zu deiner Krippen

und preisen mit erfreuten Lippen,

was du uns zubereit;

die Dunkelheit verstört uns nicht

und sahen dein unendlich Licht.

6. Choral

Lob sei Gott, dem Vater, ton,

Lob sei Gott, sein’m ein’gen Sohn,

Lob sei Gott, dem Heilgen Geist,

immer und in Ewigkeit!

Dominik Wunderlin

Ladies and Gentlemen!

Allow me to begin with the rather bold thesis that there is never as much singing as in the Christmas festive season, starting with the 1st Sunday in Advent – and which, depending on the denomination, ends on Epiphany / Epiphany Day or only on the day of the Presentation of the Lord (Candlemas). It is not only the numerous choral concerts in halls and churches that come to mind here, but also the many occasions that occur in the calendar, whether they are liturgical, pious or even purely profane in nature.

I would like to take this opportunity to recall some of them: Advent devotions with singing at the lighting of a new candle (popular with the Pietists following Wichern), Rorate celebrations, carol singing, nativity, school and club Christmas celebrations, forest Christmas celebrations by youth groups, family Christmas, Kurrende singing on Christmas Eve, New Year’s carol singing, Epiphany singing – and of course the festive singing by choirs and the people at church services during these weeks and especially at midnight mass and at Christmas. The repertoire is rich, appropriate to the various feast days. It is obvious, of course, that the songs in which the events of the Holy Night are told are mainly sung around Christmas.

As a cultural scientist, I am primarily concerned in this reflection with the tradition of Jesus in the manger, so I was surprised to see how often the word KRIPPE is explicitly found in the older hymns of our church hymnals. I am now happy to reveal the findings to you: the word for Christ’s first place of rest does not occur as often as you might expect. However, the authors who mention the cot are usually no strangers to it:

In the song “Ein Kind geboren zu Betlehem” from the 15th century, but based on the hundred years older original “Puer natus in Betlehem”, the 2nd verse begins with “Hier liegt es in dem Krippelein” and in verse 3 we also hear about the ox and donkey, who live in a stable inseparably with the Holy Family.

The hymn “In dulcis jubilo” is also pre-Reformation and begins with the words: “Unser Herzens Wonne liegt in praesepio und leuchtet wie die Sonne matris in gremio” (translated: Our baby Jesus lies in the manger and shines like the sun on his mother’s lap). Incidentally, the macaronic poem, because it is a mixture of two languages, is attributed to the mystic Heinrich Seuse, who was once active in our region; among the musical arrangers, we encounter Johann Sebastian Bach in two chorale preludes (for connoisseurs: BWV 608 and 729).

We can also find Martin Luther’s famous Christmas carol “Vom Himmel hoch, da komm ich her”, where we sing in the 5th verse: “So notice now the sign right: the manger, little wind so bad; there you will find the child laid …”

The cantor and teacher Nikolaus Herrmann was a younger contemporary of the great reformer and there is evidence of a direct connection via a letter! His numerous Protestant hymns include “Lobt Gott, ihr Christen alle gleich” (Praise God, all Christians alike), where the second verse contains the line about the Christmas story: ” … it lies there miserably naked and bare in a manger.”

Let’s close the list with the equally well-known Christmas carol by the prolific theologian Paul Gerhardt from the middle of the 17th century, which begins with “Ich steh an deiner Krippe hier”. And who composed the melody to it: our own Johann Sebastian Bach, albeit a good eighty years later.

And Bach’s Advent cantata “Nun komm, der Heiden Heiland” is at the centre of this evening. And the words are in the 5th movement:

“We honour this glory / and now approach your manger / and praise with joyful lips / what you have prepared for us.”

In contrast to two other movements in this cantata, which were written by Martin Luther, this movement is in an unknown hand.

As already mentioned, I am focussing here on the manger in which Jesus was laid after his birth. This is written in the Gospel of Luke chapter 2, verse 7:

” And she gave birth to her son, the firstborn. She wrapped him in swaddling clothes and laid him in a manger, because there was no room for them in the inn.”

The word “manger” appears twice more in this Gospel. But where it was exactly – in a grotto, in a stable ? – and who was actually present at the birth apart from Joseph is not recorded. Nor do we know what the manger looked like: Was it a feeding trough made of planks or a woven basket or merely a straw-lined recess in the floor, as shown in the Church of the Nativity in Bethlehem?

When we talk about the nativity scene today, it should be noted that the term “nativity scene” was only used in the 17th century to describe the mostly three-dimensional representation of a biblical event, be it the Passion story, the miracle of Pentecost or – and this of course primarily – the events on Christmas Eve with the homage paid by the shepherds and the later visit of the Magi – and always the star and perhaps also an angel with the banner “Gloria in excelsis Deo” above it. We encounter such things in churches during the Christmas season, but more often in public spaces and, of course, in the home. The artistic demands, the size, the choice of materials, the colours, the design of the surroundings and the number of figures vary. Some nativity scenes focus on the nuclear family, others have more figures and often show several biblical scenes that once took place at different times. Side scenes are particularly popular in Italian nativity scenes, where even the pizza baker, the ice-cream seller and the blacksmith at the anvil are not missing – and the gestures of many figures suggest that things are really loud here. So nothing about a quiet night! However, in my opinion, it is linked to the message that Jesus was born into a world full of life and not into a cemetery.

For many people, nativity scenes are something for the heart and soul, and many people feel a childlike joy when looking at them. There is often little room for the thought that a nativity scene occasionally crosses the line into religious kitsch. This is because some nativity scene makers take refuge in an idealised world. But as we know, our world has become complicated, and so even ” Political Correctness” no longer stops at nativity scenes. Only a few years ago – we may remember the discussion about the nativity scene in Ulm Minster – the view that the coloured wise men in a nativity scene are evidence of racism because they are usually portrayed in an exaggerated and discriminatory way began to take hold. For this reason, a large ethnographic museum in Basel also decided to leave a blank space this year; the third man, we call him Melchior, is therefore consistently missing, while at the same time he is constantly doing his rounds on an oversized Christmas pyramid at the Basel Christmas market together with Kaspar and Balthasar. I wonder what his somewhat puzzled look is supposed to mean about what is happening at the market. Is he perhaps also wondering why some of his brothers, sculpted by white hands, are no longer allowed into the cot stable?

But let’s leave that open for now and turn to a speciality that we often encounter in Central Switzerland and especially here in the entire Lake Constance region, indeed in the whole of Southern Germany , namely the crate cots and Christ Child boxes. The former are nativity scenes, enclosed in a glass display case, which are taken out of the réduit before Christmas and at best have to be dusted off. No wonder this type of nativity scene is known in specialist circles as a “lazy nativity scene”. This may be an accurate description in the judgement of a hard-working cot maker who spends hours and days building and assembling his cot. But the amount of time it takes to build the sacred event into a box that you also construct yourself does not have to be any less. Even nativity scene viewers who look closely can only judge the effort involved to a limited extent. A landscape is created, little houses are built, figurines are modelled and carefully dressed – and moss, lichen, twigs, stones and shells are found in nature and fitted into the scenery. And all miniaturised, of course!

Many of these nativity scenes were created in the Baroque period and up until the 19th century. They were designed by nuns who often created little worlds of wonder in their cells for the praise of God and the joy of people. Quite a few works were also created as gifts for their own families. This is particularly evident in those boxes that show a nun in her cell, standing devoutly before a baby Jesus in his cot. Such arrangements remind us of the strong and devoted devotion to the infant Jesus during the high festive season, especially in our nunneries.

The so-called ” spiritual nativity scene” developed in the Baroque period, probably going back to the Infant Jesus isions of the Middle Ages: there were devotional and edification booklets such as the printed work “Unser l(ieben) Frawen Kindbethschatz”, which first appeared in Cologne in 1660 and served as a guide for the (quote) “devout soul” to prepare the birth of Christ in their hearts and then lovingly care for the child. This spiritual nativity scene is hardly cultivated in today’s women’s convents, indeed it has mostly been forgotten. However, those little caskets have come down to us, which often only contain a Christ Child, who often lies on a cross and thus consciously points to the end of the earthly life of our Son of God.

The Christ Child in the boxes is often fanned, i.e. a swaddled child, which is reminiscent of the once common custom of nursing babies, which we also encounter almost exclusively in many, especially in the early depictions of the Christmas story. These Christ Child dolls are also the work of nuns, lovingly and elaborately designed, often with silk and brocade and a wax head: These dolls were also used for religious-mystical contemplation and they were both ” heavenly bridegroom” and “comforter of souls”. In their depiction and decoration, they often resemble the Augustinerkindl in Munich’s Bürgersaal church and the Bambinello dell’ara coeli (near the Capitol in Rome). Like the Loreto Child in Salzburg and the Sarner Jesulein, they are testimonies to an intimate veneration of the Infant Jesus that is also cultivated as a pilgrimage.

In the south in particular, you may see the straw-filled manger in front of the altar still empty at the start of midnight mass. However, at a sign, the Bambino Gesù is then brought from the sacristy by a vicar or the verger during the Christmas mass and placed in the manger.

This festive act is not dissimilar to the weighing of children that was once practised in our Catholic regions. This Christmas custom has been documented since the High Middle Ages and was practised in monasteries, churches and often also in private settings. An often life-size Christ Child figure was held in the arms of clerics or nuns during a special celebration and pious lullabies were sung. The Christ Child doll was often also passed through the pews. We have the Protestant theologian and reformer Thomas Kirchmayer (also known as Thomas Naogeorgus) to thank for the report of children dancing in front of the cot, which was set up in front of the altar, and the adults would have clapped their hands. There is similar evidence from the Saxon Ore Mountains of the 19th century, for example . According to the Austrian folklore professor Victor von Geramb, the cot custom not only received its special warmth and intimacy through the cradling of the child, but also its very existence.

As just mentioned, the beginnings of this Christmas church custom go back many centuries and started far earlier than the nativity scene. However, the idea of creating scenic representations of the Christmas story only dates back to the Counter-Reformation period. It was not until the 20th century that the nativity scene increasingly found its way into the Protestant-Reformed milieu. As a result, the nativity scene, which was once only used by Catholics, and the Christmas tree, which was initially only decorated by Protestants, have become ecumenical customary props and hopefully take us away for more than just a brief moment from today’s everyday life, which has often become so cold and forbidding.

I hope that I have contributed to this with this brief and summarised excerpt from the almost immeasurably broad and multifaceted Christmas tradition and, above all, that I have not caused any confusion. For when we – following the text – approach the cot in this present-day Bachk antate, we do so at least in our thoughts, just as the shepherds were allowed to do two thousand years ago. But may we today also be allowed to approach a lovingly designed nativity scene with our hearts and minds, to silently rejoice at the good news that has been staged and – if appropriate – to hold a meditative prayer.

Dominik Wunderlin, cultural scientist, Basel

This text has been translated with DeepL (www.deepl.com).