Lobet Gott in seinen Reichen

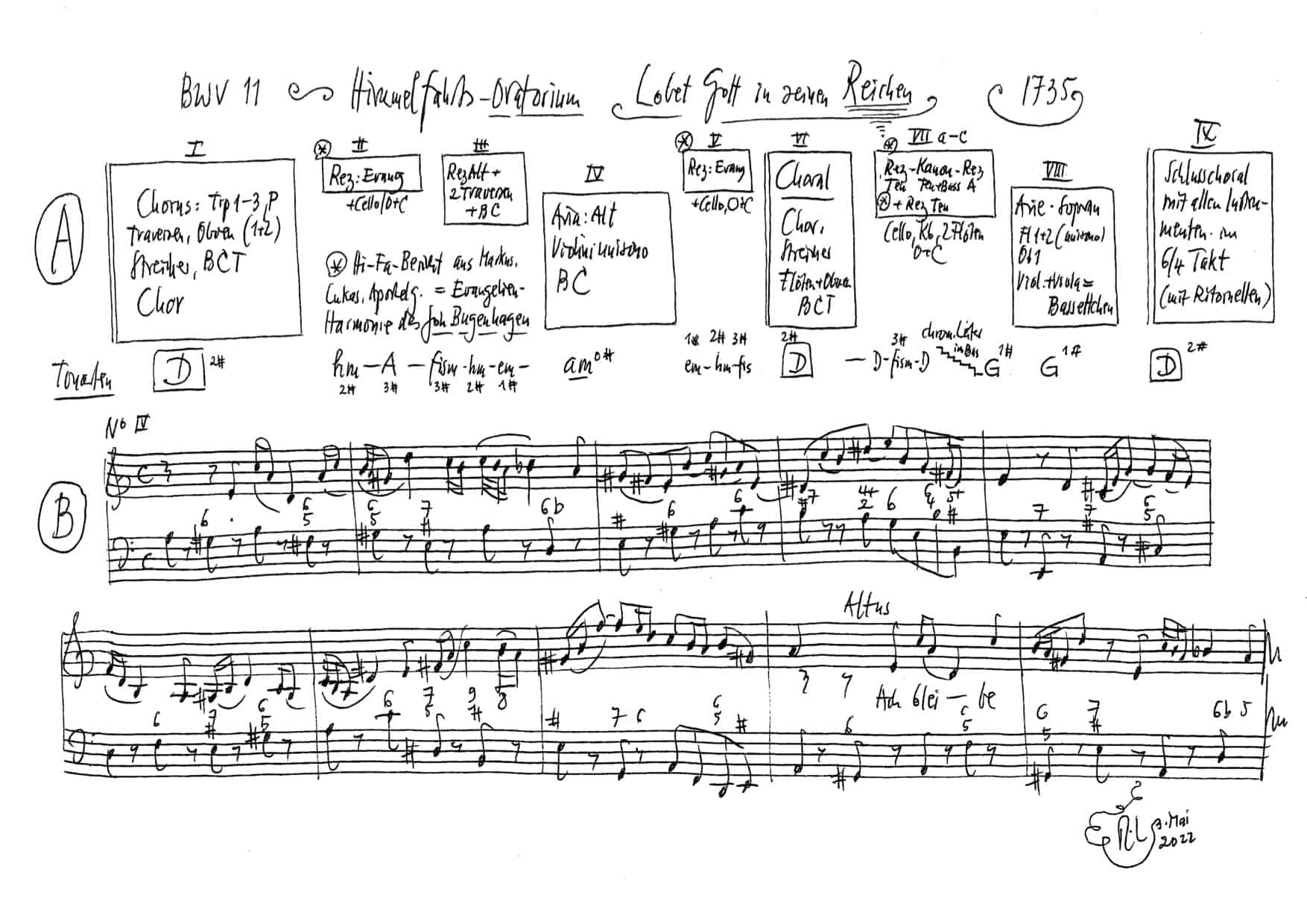

BWV 011 // for Ascension

(Laud to God in all his kingdoms) for soprano, alto, tenor and bass, vocal ensemble, trumpet I–III, timpani, transverse flute I+II oboe I+II, strings and basso continuo

Would you like to enjoy our videos ad-free? Subscribe to YouTube Premium now...

Workshop

Reflective lecture

Bonus material

Choir

Soprano

Cornelia Fahrion, Linda Loosli, Simone Schwark, Susanne Seitter, Alexa Vogel, Anna Walker

Alto

Nanora Büttiker, Antonia Frey, Stefan Kahle, Francisca Näf, Sarah Widmer

Tenor

Clemens Flämig, Manuel Gerber, Joël Morand, Walter Siegel

Bass

Johannes Hill, Christian Kotsis, Valentin Parli, Serafin Heusser, Tobias Wicky

Orchestra

Conductor

Rudolf Lutz

Violin

Eva Borhi, Peter Barczi, Christine Baumann, Petra Melicharek, Dorothee Mühleisen, Ildikó Sajgó, Judith von der Goltz

Viola

Martina Bischof, Sonoko Asabuki, Matthias Jäggi

Violoncello

Maya Amrein, Daniel Rosin

Violone

Markus Bernhard

Trumpet

Patrick Henrichs, Peter Hasel, Klaus Pfeiffer

Timpani

Martin Homann

Transverse flute

Tomoko Mukoyama, Sarah van Cornewal

Oboe

Katharina Arfken, Clara Espinosa

Bassoon

Gilat Rotkop

Harpsichord

Thomas Leininger

Organ

Nicola Cumer

Musical director & conductor

Rudolf Lutz

Workshop

Participants

Rudolf Lutz, Pfr. Niklaus Peter

Reflective lecture

Speaker

Jean-Paul Deschler

Recording & editing

Recording date

13/05/2022

Recording location

Teufen AR (Schweiz) // Evangelische Kirche

Sound engineer

Stefan Ritzenthaler

Producer

Meinrad Keel

Executive producer

Johannes Widmer

Production

GALLUS MEDIA AG, Schweiz

Producer

J.S. Bach-Stiftung, St. Gallen, Schweiz

Librettist

First performance

19 May 1735, Leipzig

Text

Poet unknown (movements 1, 3, 4, 7b, 8)

Luke 24:50-51 (movement 2)

Acts 1:9 and Mark 16:19 (movement 5)

Johann Rist (movement 6)

Acts 1:10-11 (movement 7a)

Luke 24:52 and Acts 1:12 (movement 7c)

Gottfried Wilhelm Sacer (movement 9)

Libretto

1. Chor

Lobet Gott in seinen Reichen,

preiset ihn in seinen Ehren,

rühmet ihn in seiner Pracht;

sucht sein Lob recht zu vergleichen,

wenn ihr mit gesamten Chören

ihm ein Lied zu Ehren macht!

2. Rezitativ — Tenor

Der Herr Jesus hub seine Hände auf und segnete seine Jünger, und es geschah, da er sie segnete, schied er von ihnen.

3. Rezitativ — Bass

Ach, Jesu, ist dein Abschied schon so nah?

Ach, ist denn schon die Stunde da,

da wir dich von uns lassen sollen?

Ach, siehe, wie die heißen Tränen

von unsern blassen Wangen rollen,

wie wir uns nach dir sehnen,

wie uns fast aller Trost gebricht.

Ach, weiche doch noch nicht!

4. Arie — Alt

Ach, bleibe doch, mein liebstes Leben,

ach, fliehe nicht so bald von mir!

Dein Abschied und dein frühes Scheiden

bringt mir das allergrößte Leiden,

Ach ja, so bleibe doch noch hier;

sonst werd ich ganz von Schmerz umgeben.

5. Rezitativ — Tenor (Evangelist)

Und ward aufgehaben zusehends und fuhr auf gen Himmel, eine Wolke nahm ihn weg vor ihren Augen, und er sitzet zur rechten Hand Gottes.

6. Choral

Nun lieget alles unter dir,

dich selbst nur ausgenommen;

die Engel müssen für und für

dir aufzuwarten kommen.

Die Fürsten stehn auch auf der Bahn

und sind dir willig untertan;

Luft, Wasser, Feuer, Erden

muss dir zu Dienste werden.

7a. Rezitativ — Tenor und Bass

Tenor (Evangelist)

Und da sie ihm nachsahen gen Himmel fahren, siehe, da stunden bei ihnen zwei Männer in weißen Kleidern, welche auch sagten:

Tenor und Bass

Ihr Männer von Galiläa, was stehet ihr und sehet gen Himmel? Dieser Jesus, welcher von euch ist aufgenommen gen Himmel, wird kommen, wie ihr ihn gesehen habt gen Himmel fahren.

7b. Rezitativ — Alt

Ach ja! so komme bald zurück: Tilg einst mein trauriges Gebärden, sonst wird mir jeder Augenblick verhasst und Jahren ähnlich werden.

7c. Rezitativ — Tenor (Evangelist)

Sie aber beteten ihn an, wandten um gen Jerusalem von dem Berge, der da heißet der Ölberg, welcher ist nahe bei Jerusalem und liegt einen Sabbater-Weg davon, und sie kehreten wieder gen Jerusalem mit großer Freude.

8. Arie — Sopran

Jesu, deine Gnadenblicke

kann ich doch beständig sehn.

Deine Liebe bleibt zurücke,

dass ich mich hier in der Zeit

an der künftgen Herrlichkeit

schon voraus im Geist erquicke,

wenn wir einst dort vor dir stehn.

9. Choral

Wenn soll es doch geschehen,

wenn kömmt die liebe Zeit,

dass ich ihn werde sehen

in seiner Herrlichkeit?

Du Tag, wenn wirst du sein,

dass wir den Heiland grüßen,

dass wir den Heiland küssen?

Komm, stelle dich doch ein!

Jean-Paul Deschler

The Ascension of Christ in Eastern Church Tradition – Iconography as a Testimony to the Christian Faith

Treasured eye and ear witnesses,

Johann Sebastian Bach celebrates the Ascension with uplifting music in this oratorio. The Eastern Churches have been celebrating the feast for two thousand years in enthusiastic hymns, with impressive rituals and images. I have been invited to tell you about this today, and I am happy to do so on the basis of the visionary, rapturous depiction that you have received as a flyer.

I would like to briefly answer your question as to how a Latin Occidental Christian comes to the Oriental traditions. It happened in two steps. The first step led from the sublime Gregorian chant to the Byzantine liturgy in Slavonic form, for which I was ordained a deacon. (In the divine service, a deacon leads the congregation through the prayers and ceremonies as an assistant to the bishop and priest). In the second step, I moved on to the Middle East, which preserves many elements of the early church to this day.

A famous Syriac manuscript of the 6th century contains the four Gospels in an Aramaic dialect, which roughly corresponds to the mother tongue of Jesus. In addition, it offers many illustrations of people and scenes from the Holy Scriptures – and in such a mature artistic form that one can recognise a long tradition whose beginnings go back close to early Christianity.

Let us be aware: the root soil of Christianity is the countries of the Near East, especially Palestine and Mesopotamia. Although the oriental way of expression in words and images is at first strange and even alien to occidental eyes and ears, it proves to be an incomparable broadening of the horizon once one gets to know it.

This consideration brings us back to the 6th century Rabbula Gospels. The miniature of Christ’s Ascension expresses, as a diagram of faith, the wording of the biblical scriptures, here the account of the Gospel and Acts of the Apostles, precisely quoted by Bach with Luther’s translation: And was lifted up visibly, and ascended up to heaven, and a cloud took him away from before their eyes, and he sitteth on the right hand of God.

On closer examination, we notice details that we can easily assign to the biblical words, e.g. the two men in white clothes who suddenly appear, address and instruct the men of Galilee. It is obvious that they are angels: Hence they are depicted with wings and the symbolic messenger’s staff (Greek ἄγγελος means “messenger”). That the men in the picture must be the twelve apostles then occurs to us when we count them. But immediately the consideration arises that after the elimination of Judas Iscariot, there were only the eleven before they made the replacement election of Matthias.

Here it becomes clear that this is not a documentation in the sense of modern historiography, although the miniature is based on a historical event. So we are surprised to find Paul among the apostles on the left side, although he is known to have fanatically persecuted Christians as a convinced Pharisee before his Damascus experience. He and Peter on the right are clearly in the foreground; they are also marked by book and key as the “princes of the apostles” and builders of the young church. Even more striking, however, is Mary standing in the centre with her arms outstretched; this posture, the central position, the royal purple of her maphorion as well as the red shoes, but above all the height with which she “towers over” the apostles and angels, so to speak, show the importance that has been attached to the Mother of God from the beginning: hundreds of hymns praise her humility and her willingness to serve as an instrument of the Incarnation and of redemption, and address her as a powerful intercessor. These hymns actually all start from the greeting of the Annunciation Angel (it begins with χαῖρε – rejoice), but do not stop at the praise of the “Blessed One”, but always flow into the praise of God. In the mystical theology of the Church, Mary as the Bride of the Holy Spirit also embodies the Church itself and is the Mother of the “communion of saints”. Finally, we are struck by the fact that she is the only one of the people present who is distinguished with a nimbus that otherwise only surrounds the heads of angels and Christ. Thus the iconography suggests that Mary, standing with both feet on earth and united with her Son, is already permeated by the divine reality.

The transcendent world is the subject of the upper register of the Rabbula miniature. Here, too, we come across some details whose interpretation is not immediately clear. However, it is possible to decipher them with regard to pictorial evidence from antiquity as well as biblical and liturgical writings. Vertically above the Mother of God, Christ can be seen in an oval gloriole. The King of Glory enters the heavenly temple and is received by the angels. Two of them carry crowns with reverently veiled hands to present them to this King.

A clear sign of divine kingship is the strange vehicle beneath the gloriole. First we see something like flames or fiery wings, then wheels on either side, and finally the heads of four living creatures arranged crosswise out of the fire: a man and a bull, a lion and an eagle; plus a hand reaching down. This is the prophet Ezekiel’s powerful and bewildering vision of the throne, which is taken up again in the Revelation of John. The biblical texts reveal that it is not easy for the visionaries to put such a face into words; and obviously it is an equally difficult task to later reproduce the details described in language in a drawing.

The disciples recognise in Jesus the Son of God; that is why they also give him the title Pantokrator (All-Ruler, All-Powerful) and Lord (in the sense of God). Already in late antiquity, Christ is depicted sitting on the heavenly throne; the gloriole of the Majestas Domini is surrounded in Eastern and later in Western forms by the four living creatures; as in Ezekiel, these represent the four main directions of the world, and since the second century they have also been regarded as symbols of the evangelists. These, namely, are to spread the message of Christ to the “four ends of the earth”. The cosmic dimension is also made clear on the miniature by the depiction of the moon and the sun in the upper corners.

The miniatures of the Rabbula Gospels show how Christian iconography, before the Byzantine iconoclastic controversy, found its way from the naturalistic representation of antiquity to the sacred realism of the cult image. Icons are capable of representing both the visible and the supersensible world – in transfigured reality, not in the naturalism and subjectivism of the Renaissance or the exuberance of the Baroque. An icon does not merely offer ecclesiastical doctrinal information, but involuntarily invites the faithful to pray, for it is the transposition of liturgical hymns in praise of God. In the Byzantine tradition, the day of the Ascension is celebrated with special rejoicing in the celebration of the Eucharist and in all the hourly prayers. The mystery of the feast is thematised in numerous allusions to biblical passages, whereby the Incarnation, the Mother of God, the “descent” and “ascent” of the Saviour as well as the Trinity are repeatedly mentioned, e.g. in the extended chants of the morning service:

Ascended in glory, King of angels,

to send us the Comforter from the Father.

Therefore we cry out:

Glory be, Christ, to your ascension.

The words of the chorale in Bach’s oratorio, with which I also conclude our reflection, also fit the idea of the Ascension, in which the upper and the lower are separated and yet united:

Now everything lies beneath you,

Except thyself;

The angels must for and for

The angels must come to wait for you.

The princes also stand on the path

And are willingly subject to thee;

Air, water, fire, earth

Must become thy servants. (6th movement)

Ascension of Christ in the Rabbula Gospels – Iconography as a Testimony of Faith

The Rabbula Codex is a famous Syriac manuscript of the 6th century,[1] which contains the four Gospels in Old Syriac, i.e. in an Aramaic dialect roughly corresponding to the mother tongue of Jesus. This manuscript is a valuable document for biblical and linguistic research; at the same time, it is highly interesting as a testimony to Christian iconography, for it offers many illustrations of persons and scenes from the Holy Scriptures – and in such a mature artistic form that one can recognise a long pictorial tradition whose beginnings go back close to early Christianity.[2] In Europe, too little awareness has been paid to the use of the manuscript as a source of inspiration.

In Europe, there is too little awareness that the root soil of the Christian faith is the lands of the Near East, especially Palestine and Mesopotamia. The culture of this region, which has grown over thousands of years, was shaped in antiquity by Semitic and Persian, by Hellenistic and Byzantine influences. Their way of expressing themselves in words and images is at first strange and even alien to occidental eyes and ears, but once you get to know them, it proves to be an incomparable broadening of the horizon.

People usually communicate in a language consisting of articulated words. But they also express themselves (intentionally or unintentionally) through body language, use the language of music – the conductor uses baton and hands as language – images and rituals are also languages, and unfortunately people often enough think they have to “let the weapons speak”.

Bible translators have always been confronted with the difficulties of understanding – not only Martin Luther in the 16th century.[3] Two hundred years after this important “dolmetzscher”[4] and reformer, the gifted musician and composer Johann Sebastian Bach[5] created works intended for the Sundays and feast days of the liturgical year. Well understood: Such cantatas and oratorios, which are performed in the concert hall today, were originally intended for liturgical use in church. This was as natural for the composer as it was for Martin, the theology professor, preacher and former Augustinian monk, who was also very musical.

The noblest kind of liturgical cult with which a people can worship God is undoubtedly the human word, when this is expressed simply and at the same time artfully in poetic form and resounds as song, also accompanied by musical instruments and rituals, in praise of God. This applies to the period of Baroque music as well as to Gregorian chant, the ancient Roman cantus, the Byzantine and Syriac tonal systems. This consideration brings us back to the time of the Rabbula Gospels. In the 6th century, the great poet-theologian and bishop Jacob of Serug[6] also lived in northern Mesopotamia. He created – similar to his model, St. Ephräm the Syrian[7] – hundreds of hymns and sermons on biblical themes and church festivals. The Memra[8] on the Ascension of Christ, with its 486 verses, is a gripping paraphrase of Luke’s account,[9] meditation, catechesis and praise – moreover, with all its poetic stylistic devices[10] a delight for the listener. A retelling can only approximate this.[11] Important to the preacher is the proclamation of the Christian truths of faith; therefore, on many occasions, he expresses himself about the divine plan of salvation, the miracle of the Incarnation of the Son of God, about the death and resurrection of Jesus, the Redemption, the Trinity. In the course of the Ascension Homily, Jacob makes a great arc from the Incarnation to the Ascension:

You, well on the throne, Mary carried in the bosom,

Thou dost dwell above, but birth here above. (v. 19 f.) … …

Down into the realm of the dead He descended to Adam,

Like a bold diver He brought up the pearl. (v. 97 f.) … …

Glorious as a priest He ascended to the sanctuary,

none else but He alone may enter it. (v. 409 f.)

It is not surprising that the Imbomon[12] of the Mount of Olives has been a destination of Holy Land pilgrims from the beginning until today. So let us return to the Rabbula Gospels to look at the miniature of the Ascension there. Like all Eastern Church icons, it expresses the wording of biblical, liturgical and hagiographical writings as a diagram of faith.

At first glance, we recognise the theme, but the division into above and below, the heavenly realm and the earthly region, is also clear. There are a number of people standing there, obviously moved or even excited, looking upwards after Christ has been lifted up before their eyes. This passage from Acts 1:9, combined with Lk 24:51 and Mk 16:19, reads in the 5th movement of Bach’s oratorio, quoting Luther’s German of 1545 exactly: “And was lifted up visibly, and ascended up to heaven, and a cloud took him away from before their eyes, and he sitteth on the right hand of God.”[13]

On close examination we notice details that we can easily assign to the biblical words, e.g. the two men in white robes (Acts 1:10) who suddenly appear, address and instruct the men of Galilee (1:11). It stands to reason that they are angels: Hence they are depicted with wings and the symbolic messenger’s staff[14] (Greek ἄγγελος means “messenger”). That the men in the picture must be the twelve apostles then occurs to us when we count them. But immediately the thought arises that after the elimination of Judas Iscariot there were only the eleven (Lk 24, 9) – they are indeed mentioned by name in Acts 1, 13 – before they made the replacement election of Matthias (Acts 1, 15-26).

Here we realise that we are not dealing with a historical documentation in the sense of modern historiography, although the miniature is based on a historical event. [15] So we are surprised to find Paul among the apostles on the left side – iconographically recognisable by his high thinker’s forehead and black beard – although he is known to have fanatically persecuted Christians as a convinced Pharisee before his Damascus experience.[16] He and Peter on the right are clearly in the foreground, and they are also marked by book and key as “princes of the apostles”[17] and builders of the young church. Even more striking, however, is Mary standing in the centre with her arms outstretched; this orante posture, the central position, the royal purple of her maphorion as well as the red shoes, but above all the height with which she “towers over” the apostles and angels, as it were,[18] show the importance that has been attached to the Mother of God from the beginning: hundreds of hymns praise her humility and her willingness to serve as an instrument of the Incarnation and of redemption, and address her as a powerful intercessor. [19] These hymns actually all start from the greeting of the Annunciation Angel (it begins with χαῖρε – rejoice),[20] but do not stop at the praise of the “Blessed”, but always flow into the praise of God.[21] In the mystical theology of the Church, Mary as the Bride of the Holy Spirit (Lk 1:35) also embodies the Church herself and is the Mother of the “communion of saints”. Finally, we are struck by the fact that she is the only one of the people present who is distinguished with a nimbus that otherwise only surrounds the heads of angels and Christ. Thus the iconography suggests that Mary, standing with both feet on earth and united with her Son, is already permeated by the “beyond”, by divine reality.

This beyond, the transcendent world, is the subject of the upper register of the Rabbula miniature. Here, too, we come across some details whose interpretation is not immediately clear. However, it is possible to decipher them with regard to pictorial evidence from antiquity as well as biblical and liturgical writings. On the picture axis vertically above the Mother of God, Christ can be seen in an oval gloriole – at least for the observer of the miniature, while a cloud has already withdrawn him from the view of the disciples (Lk 1, 9). He stands upright, his right hand raised in blessing, holding an open scroll in his left.[22] This is reminiscent of the custom of Germanic warriors to choose a leader by raising a shield. [23] But here the clipeus has become a glory that belongs only to God, the King of Glory,[24] who enters the heavenly temple and is received with rejoicing by the angels.[25] Two of them carry crowns with reverently veiled hands to present them to this king.

A clear sign of divine kingship is the strange vehicle beneath the gloriole. First we see something like flames or fiery wings, then wheels on either side, and finally the heads of four living creatures arranged crosswise out of the fire: a man and a bull, a lion and an eagle; plus a hand reaching down. This is the mighty and confusing throne vision of the prophet Ezekiel (Ez 1, 4 ff.), which is taken up again in the Revelation of John (Rev 4, 2 ff.). The biblical texts reveal that it is not easy for the seers to put such a face into words; and obviously it is an equally difficult task to reproduce later in a drawing the details described in language,[26] the appearance of the four beings and the many-eyed wheel rims and wings, the flames and lightning as well as the movement of the four wheels, a fortiori the appearance of the “Throne One.”[27]

The disciples of Jesus recognise in him the Son of God (Mt 16:16); therefore they also give him the title Pantokrator (All-Ruler, All-Powerful)[28] and Lord (i.e. of God). [29] Already in the late antiquity Christ is depicted sitting on the heavenly throne; the gloriole of the Majestas Domini is surrounded in eastern and later in western forms – in the apsidal dome of a church and in the tympanum of a portal – by the four living creatures; these represent, as in Ezekiel, the four main directions of the world, and since the 2nd century they are also regarded as symbols of the evangelists. 30] These namely have the task of spreading the message of Christ to the “four corners of the earth”. But this expression means more: it is the universe that is to be filled with the word and power of God, because God’s plan of salvation includes the whole of creation (Rom 8:22). Finally, the cosmic dimension is also made clear on the Rabbula miniature by the depiction of the moon and the sun in the upper corners.[31]

The miniatures of the Rabbula Gospels show how Christian iconography, before the Byzantine iconoclastic controversy,[32] found its way from the naturalistic mode of representation of antiquity to the sacred realism of the cult image. Icons are capable of reproducing both the visible and the supersensible world, hence words of Scripture – in transfigured reality, not in the naturalism and subjectivism of the Renaissance or the exuberance of the Baroque – and so, as “windows on eternity”, they allow us to glimpse the world beyond time and space. An icon not only offers ecclesiastical doctrinal information, but also invites the faithful involuntarily to pray, for it is the transposition of liturgical hymns in praise of God. In the Byzantine tradition, the day of the Ascension is celebrated with special jubilation in the celebration of the Eucharist and in all the hourly prayers.[33] The mystery of the feast is thematised in numerous allusions to biblical passages, whereby the Incarnation, the Mother of God, the “descent” and “ascent” (cf. Eph 4:9 f.) of the Saviour as well as the Trinity are mentioned again and again, e.g. in the extended chants of the morning service:

Ascended in glory, King of angels,

to send us the Comforter from the Father.

Therefore we cry out:

Glory be, Christ, to thy ascension.[34]

The words of the chorale in Bach’s oratorio are equally fitting for the contemplation of the Ascension, in which the upper and the lower are divorced and yet united:

Now all lies beneath thee,

Except thyself;

The angels must for and for

The angels must come to wait for you.

The princes also stand on the path

And are willingly subject to thee;

Air, water, fire, earth[35]

Must become thy servants. (6th movement)[36]

Selected literature

Bach, Johann Sebastian, Origin of the Musical Bach Family. 1735, in: Bach, Peter, Bach über Bach. www.bachueberbach.de

Bedjan, Paul (Ed.), S. Martyrii, qui et Sahdona, quæ supersunt omnia, Paris/Harrassowitz, Leipzig 1902.

Bedjan, Paul (Ed.), Homiliæ selectæ Mar-Jacobi Sarugensis, Vols. I-V, Paris/Harrassowitz, Leipzig 1905-1910, Reprint ed. Sebastian Brock, Piscataway 2006 (with supplementary volume VI).

Bloedhorn, Hanswulf, “The Eleona and the Imbomon in Jerusalem: a double church complex on the Mount of Olives?”, in: Akten des XII. International Congress of Christian Archaeology 1 (ed. Ernst Dassmann and Josef Engemann), Aschendorff, Münster 1995, pp. 568-571.

Brodersen, Kai (ed. and ed.), Aetheria/Egeria, Reise ins Heilige Land: Lateinisch-deutsch. Tusculum Collection. De Gruyter, Berlin/Boston 2016.

Brück, Helga, Von der Apfelstädt und der Gera zum Missouri. 500 Jahre Thüringer Musikerfamilie Bach (Schriften des Vereins für die Geschichte und Altertumskunde von Erfurt, Vol. 7). Glaux, Jena 2008.

Cecchelli, Carlo/Furlani, Giuseppe/Salmi, Mario (eds.), The Rabbula Gospels. Facsilime Edition of the Miniatures of the Syriac Manuscript Plut. I, 56 in the Medicaean-Laurentian Library. Urs Graf, Olten/ Lausanne 1959.

Chia, Roland, “Re-reading Bach as a Lutheran Theologian”, in: Dialog: A Journal of Theology, Vol. 47, No. 3, Fall 2008, 161-270.

Chojnacki, Stanisław, “The Four Living Creatures of the Apocalypse and the Imagery of the Ascension in Ethiopia”, in Bulletin de La Société d’archéologie Copte 23 (Institut Français d’archéologie orientale, Le Caire 1981), 159-181.

Geyer, Paul (ed.), Itinera Hierosolymitana saecvli IIII-VIII (Corpvs scriptorvm ecclesiasticorvm latinorvm, 39). Kaiserl. Akad. Wiss. Temsky, Vienna 1898 [Itinerarium Burdigalense (333-334), pp. 1-33; Peregrinatio Aetheriae (381-384), pp. 35-101].

Golitzin, Alexander (Trsl. and introd.), Jacob of Sarug’s Homily on the Chariot that Ezekiel Saw (Texts from Christian Late Antiquity 3, ed. George Kiraz). Gorgias, Piscataway 2016.

Grohmann, Adolf, Aethiopische Marienhymnen. Teubner, Leipzig 1919.

Kollamparampil, Thomas (Trsl. and introd.), Jacob of Sarug’s Homily on the Ascension of Our Lord (Texts from Christian Late Antiquity 24, ed. George Kiraz). Gorgias, Piscataway 2010.

Loewe, Andreas, “God’s Capellmeister”: The Proclamation of Scripture in the Music of J. S. Bach, in: Pacifica 24 (June 2011), 141-171.

Luther, Martin, Biblia: Das ist: Die gantze Heilige Schrifft: Deudsch… Wittemberg M.D.XLV. (3 vols., ed. Hans Volz). Deutscher Taschenbuch-Verlag, Munich 1974.

Megenberg, Konrad von, Das Buch der Natur. The first natural history in the German language (ed. Franz Pfeiffer). Karl Aue, Stuttgart 1861. repr. Georg Olms, Hildesheim 1971.

Petzoldt, Martin (ed. et al.), Bach als Ausleger der Bibel: Theologische und musikwissenschaftliche Studien zum Werk Johann Sebastian Bach. Vandenhoeck and Ruprecht, Göttingen 1985, 77-95.

Petzoldt, Martin, ‘The Theological in Bach Research (2007)’, in Compositional Choices and Meaning in the Vocal Music of J. S. Bach, ed. M. A. Peters (Lanham, 2018), 103-120.

Prinz, Otto (ed.), Itinerarium Egeriae (Peregrinatio Aetheriae). 5th, revised and ed. ed., Winter, Heidelberg 51960.

Rathey, Marcus, “Preaching and the Power of Music: A Dialogue between the Pulpit and Choir Loft in 1689”, in: Yale Journal of Music & Religion, Vol. 1, Iss. 2, art. 4.

Romm, James S., The Edges of the Earth in Ancient Thought: Geography, Exploration, and Fiction. University Press, Princeton, NJ 1992.

Ščepkina, Marfa Vjačeslavovna (ed.), Miniatjury Chludovskoj psaltyri. Grečeskij illjustrirovannyj kodeks IX veka (Russ.). Iskusstvo, Moskva 1977.

Wessel, Klaus, “Ascension”, in: Reallexikon zur byzantinischen Kunst (ed. Klaus Wessel and Marcell Restle, Hiersemann, Stuttgart, vol. 1 ff., 1966 ff.), 2, 1224-1262.

————————————-

Treatise for reflection on the performance of the Ascension Oratorio, Teufen, 13 May 2022, jpd.

————————————-

[1] The colophon fol. 292r gives the year 586 as the time of composition, the monastery of St. John at Beth Zagba as the place of origin and a monk named Rabbula as the scribe. Today the manuscript is in the Biblioteca Laurenziana in Florence. – The full-page miniature described below occupies fol. 13v.

[2] There are various reasons for the widespread disappearance of icons in churches of the Syriac tradition. On the one hand, the countries of the Near and Middle East have come under the rule of Islam, which is hostile to images, and on the other hand, they have allowed themselves to be influenced by the religious art of the West.

[3] Of the often ingenious translations, I mention here only the Septuagint (Greek version of the Old Testament, from the 3rd century BC), the Diatessaron (Tatian’s Syriac Gospel Harmony, 2nd century BC), the Latin Vulgate (Latin), and the Greek Bible. ), the Latin Vulgate (Jerome, c. 400), the Gothic Bible (Wulfila, 4th c.), the Slavic Bible (Cyril and Methodius, 9th c.), the numerous German versions in the Middle Ages (from the 8th c.).

[4] For “translator” in the “Sendbrief vom Dolmetzschen”, Luther 3, 244*.

[5] 1685-1750; the Bach family, widely spread in Thuringia and Saxony, descended from Veit Bach, who had left Ungerndorf in Bohemia (not Hungary!) in the 16th century because of his Lutheran confession.

[6] 451-521; Serug (south-east Anatolia), in ancient times Batnae, today trk. Suruç.

[7] 306-373, deacon, the most important Syrian church teacher.

[8] The Memra or West Syriac Mimro (“speech, saying”) is a sermon combining high poetic level, great theological content and didactic skill, is a popular form of catechesis among various Syriac Church Fathers. Bedjan included the homily in S. Martyrii… pp. 808-832, with the title ܕܝܼܠܹܗ ܕܩܲܕܝܼܫܵܐ ܡܵܪܝ ܝܲܥܩܘܿܒ݂ ܡܐܡܪܐ ܕܥܲܠ ܣܘܼܠܵܩܹܗ ܕܡܵܪܲܢ ܕܠܲܫܡܲܝܵܐ܂ – Memra on the Ascension [d. i. the ascension] of our Lord (here rendered according to Bedyan with East Syriac vocalisation, but not in Chaldean script, but in Estrangela).

[9] Lk 24:50-52; Acts 1:4-11; plus exegetical allusions to Ps 47:6; Eph 2:6; Col 3:1; Heb 9:11-24.

[10] Strict dodecasyllabus, parallelism, word play, onomatopoeia, assonance, consonance, metaphor, comparison, personification, rhetorical question, contrasts, repetition (anaphora, diaphora, accumulation): The Mount of Olives is frequently mentioned as the place of the event, six times in vv. 161-169 alone.

[11] After all, the German language has many possibilities to create sounds and idioms in poetry that are similar to or replace those of the Syriac original, e.g. the different types of rhyme (end, beginning, staff, internal, percussive rhyme); the variety of forms of conjugation and declension allows a great flexibility in word order, which is not possible in a translation into contemporary French and English. The Syriac twelve-syllable metre can be well reproduced as a Trochaic senar.

[12] Already the travelogues of the 4th century (e.g. those of Bordeaux and of Egeria) speak of this. Imbomon < ἐν βωμῷ – “on the step, elevation, height, hill”; perhaps a church is meant (Egeria 35, 4), a precursor of the octagonal Ascension Chapel or Ascension Mosque on the Mount of Olives (12th c.); the LXX translates Heb. בָמָה – “(cult) height” with βωμός (e.g. Num 21, 28, otherwise also with ὑψηλόν, e.g. 3 Kg 3, 2).

[13] Passion harmonies, mostly in Low German but also in High German and Latin, were published by Luther’s friend and collaborator Johannes Bugenhagen (1485-1558) from 1524 onwards; the work, later completed as the Gospel Harmony (published in 1566 as the Monotessaron by Paul Krell), may have influenced the idea of combined Gospel passages in oratory.

[14] The caduceus (Grch. κηρύκειον) was an attribute of the messenger of the gods Ἑρμῆς (Hermes, Lat. Mercurius – Mercury) in antiquity as a herald’s staff – along with wings on hat and sandals.

[15] Even despite the differences in exegesis, the fact of Christ’s reception into God’s glory remains.

[16] Cf. the accounts Acts 8:1-3; 9:1 ff; 22:4 ff; 26:5 ff.

[17] The title Πρωτοκορυφαῖοι (literally “first exalted one”) of the Byzantine tradition has its basis in numerous scriptural passages such as the designation of Peter as πρῶτος (Mt 10:2).

[18] Already in the art of ancient Egypt, the perspective of meaning was an important stylistic device.

[19] The magnificent mosaic of the Virgo orans (as “God’s Mother of the indestructible wall”) in the altar apse of St. Sophia’s Cathedral in Kyjiv (11th century, about 5.5 m high) is reminiscent of the Rabbula miniature in several details.

[20] Syr. ܫܠܵܡ ܠܹܟܝ – peace (i. S. salvation) to you. The passages at Luke 1:28 and 1:42 form the Hail Mary prayer to this day.

[21] The famous Byzantine hymn Akathistos does this in 24 stanzas and 144 chairetisms meditating on the mystery of the Incarnation.

[22] An apse fresco in Bawit, probably also from the 6th century and almost identical in depiction to the Rabbula miniature, shows Christ seated on a throne in the mandorla.

[23] The Western Roman Emperor Julian (the Apostate) was also elected in this way at Lutetia (Paris) in 360, and a marginal miniature to Ps 20:4 ff. LXX in the Chludov Psalter depicts the enthronement of Hezekiah (721 B.C.) thus.

[24] The psalm-word βασιλεὺς τῆς δόξης (Ps 23, 7 ff.) is frequently affixed to the titulus bar on icons of the Crucified instead of Pilate’s inscription Jesus of Nazareth, King of the Jews (Jn 19, 19, usually abbreviated Grch. ΙΝΒΙ, lat. INRI, ksl. ІНЦІ, syr. ܝܢܡܝ , eth. ኢናንአ). In the language of John the Evangelist, “exaltation” has the double sense of “crucifixion” and “glorification”, cf. John 3:14; 8:28; 12:32-34; also Acts 2:33; 5:31.

[25] Various Psalm passages are regarded as prefiguring Christ’s ascension: 23:7 ff; 28:1 f.; 46:6; 109:1 f. LXX.

[26] This difficulty exists for visions and auditions of all times until today – e.g. in Isaiah (c. 740 B.C., cf. Is 6, 1 ff.), Ezekiel (c. 590 B.C., Ez 1, 4 ff.), Paul (2 Cor 12, 2-4), Hildegard von Bingen (d. 1179, cf. Scivias 1, 3), Black Elk (Lakota: Hehaka Sapa, d. 1950).

[27] It is interesting to compare this with the illustration on the subject of the throne chariot (or tetramorph), which Luther took over from Lucas Cranach the Younger from 1541 onwards (Luther 2, 1401), as well as Luther’s modified translation and his interpretation in the preface (2, 1392 f.). – To the Ezekiel vision, Jacob of Serug dedicates a Memra which deals extensively (1400 verses!) with all the details of the throne chariot and its prefigurative meaning – in Bedjan Homiliæ… as no. 125 in Vol. IV, 543-610, titled ܡܐܡܪܐ ̇ ܩܒܗ ̇ ܥܲܠ ܗܵܝ ܡܲܪܟܲܒ̣ܬ̣ܵܐ ܕܲܚܙܵܐ ܚܲܙܩܝܼܐܹܝܠ ܢܒ̣ܝܼܵܐ܂܁܁܁ – Memra CXXV on the chariot which the prophet Ezekiel saw… (again rendered after Bedyan with East Syriac vocalisation, but not in Chaldean script, but in Estrangela).

[28] In the LXX παντοκράτωρ stands for Heb. שַׁדַּי (Job 5, 17 pass.), in NT 2 Cor 6, 18; Rev 1, 8 pass. Cf. τὰ πάντα i. s. of “the universe, the cosmos, the whole creation” (Ps 102, 19 LXX; Wis 9, 1; 15, 1; Jn 1, 3; 1 Cor 8, 6; Eph 1, 10; Col 1, 16; Heb 1, 2 f. pass.; Rev 4, 11).

[29] Cf. Jn 20:29; the LXX regularly has κύριος for Heb. יְהוָה (Ex 15, 3 pass.).

[30] According to Irenaeus (d. 202) the ζῷα of Ez 1, 10 refer to the four canonical Gospels with the assignment lion-John, bull-Luke, man-Matthew, eagle-Mark (Adv. Haer. 3, 11, 8); since Jerome (d. 420) lion and eagle are interchanged in the West.

[31] Personified by faces similar to those on icons of the crucifixion (cf. Mk 15, 33; Lk 23, 44; Acts 2, 20).

[32] It lasted from the politically motivated iconoclastic edict (?) of Emperor Leo III in 726 until the victory of the theologically based veneration of images (Horos of the Council of Nikaia in 787) under Empress Theodora II by decree of 843.

[33] Ascension belongs to the twelve principal feasts (δωδεκαόρτιον) of the Church year, 40 days after Easter; the preceding Wednesday is celebrated as the conclusion (ἀπόδοσις) of Easter and at the same time as the preliminary celebration (προεόρτιον) of Ascension.

[34] Orthros, Canon of John Monachos (8th/9th century), 4th Ode, 2nd Troparion.

[35] The doctrine of the four elements as the basic building materials of the entire cosmos has played a role since the Greek philosophers via astrology and alchemy as well as the natural doctrines of the Middle Ages up to depth psychology.

[36] The text was probably written by Picander (Christian Friedrich Henrici, 1700-1764).

This text has been translated with DeepL (www.deepl.com).