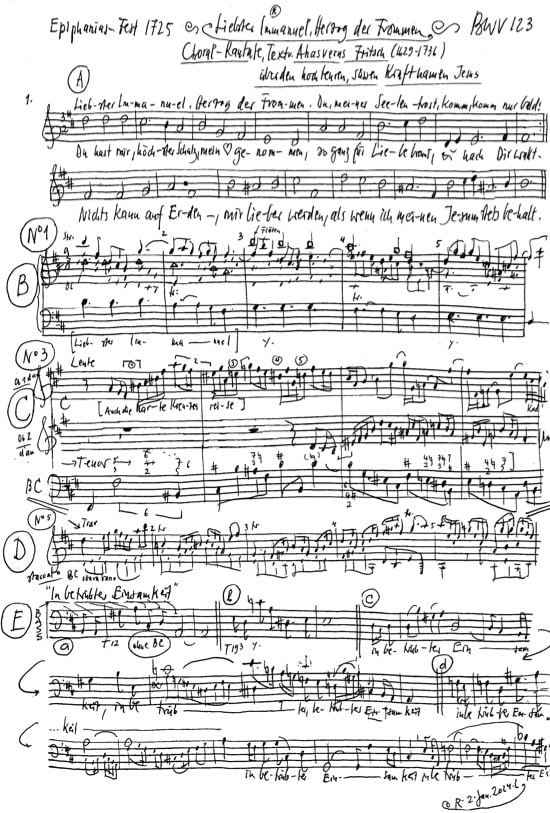

Liebster Immanuel, Herzog der Frommen

BWV 123 // Epiphany

(Dearest Emanuel, Lord of the faithful) for alto, tenor and bass, vocal ensemble, transverse flute I+II, oboe d’amore I+II, strings and basso continuo

Would you like to enjoy our videos ad-free? Subscribe to YouTube Premium now...

Workshop

Reflective lecture

Choir

Soprano

Lia Andres, Linda Loosli, Simone Schwark, Susanne Seitter, Noëmi Tran-Rediger, Baiba Urka

Alto

Anne Bierwirth, Antonia Frey, Laura Kull, Lea Scherer, Jan Thomer

Tenor

Manuel Gerber, Tobias Mäthger, Christian Rathgeber, Walter Siegel

Bass

Jean-Christophe Groffe, Christian Kotsis, Daniel Pérez, Philippe Rayot, William Wood

Orchestra

Conductor

Rudolf Lutz

Violin

Renate Steinmann, Salome Zimmermann, Elisabeth Kohler, Monika Baer, Lisa Herzog-Kuhnert, Patricia Do

Viola

Susanna Hefti, Claire Foltzer, Matthias Jäggi

Violoncello

Jakob Valentin Herzog, Hristo Kouzmanov

Violone

Markus Bernhard

Transverse flute

Tomoko Mukoyama, Rebekka Brunner

Oboe d’amore

Katharina Arfken, Clara Espinosa Encinas

Bassoon

Gilat Rotkop

Harpsichord

Thomas Leininger

Organ

Nicola Cumer

Musical director & conductor

Rudolf Lutz

Workshop

Participants

Rudolf Lutz, Pfr. Niklaus Peter

Reflective lecture

Speaker

Nina Kunz

Recording & editing

Recording date

12/01/2024

Recording location

Trogen AR (Switzerland) // Evang. Kirche

Sound engineer

Stefan Ritzenthaler

Producer

Meinrad Keel

Executive producer

Johannes Widmer

Production

GALLUS MEDIA AG, Schweiz

Producer

J.S. Bach-Stiftung, St. Gallen, Schweiz

Librettist

First performance

6 January 1725, Leipzig

Text

Ahasverus Fritsch (movements 1, 6); unknown source (movements 2–5)

Libretto

1. Chor

Liebster Immanuel, Herzog der Frommen,

du, meiner Seelen Heil, komm, komm nur bald!

Du hast mir, höchster Schatz, mein Herz genommen,

so ganz vor Liebe brennt und nach dir wallt.

Nichts kann auf Erden

mir liebers werden,

als wenn ich meinen Jesum stets behalt.

2. Rezitativ — Alt

Die Himmelssüßigkeit, der Auserwählten Lust,

erfüllt auf Erden schon mein Herz und Brust,

wenn ich den Jesusnamen nenne

und sein verborgnes Manna kenne:

Gleichwie der Tau ein dürres Land erquickt,

so ist mein Herz

auch bei Gefahr und Schmerz

in Freudigkeit durch Jesu Kraft entzückt.

3. Arie — Tenor

Auch die harte Kreuzesreise

und der Tränen bittre Speise

schreckt mich nicht.

Wenn die Ungewitter toben,

sendet Jesus mir von oben

Heil und Licht.

4. Rezitativ — Bass

Kein Höllenfeind kann mich verschlingen,

das schreiende Gewissen schweigt.

Was sollte mich der Feinde Zahl umringen?

Der Tod hat selbsten keine Macht,

mir aber ist der Sieg schon zugedacht,

weil sich mein Helfer mir, mein Jesus, zeigt.

5. Arie — Bass

Laß, o Welt, mich aus Verachtung

in betrübter Einsamkeit!

Jesus, der ins Fleisch gekommen

und mein Opfer angenommen,

bleibet bei mir allezeit.

6. Choral

Drum fahrt nur immer hin, ihr Eitelkeiten,

du, Jesu, du bist mein, und ich bin dein;

ich will mich von der Welt zu dir bereiten;

du sollst in meinem Herz und Munde sein.

Mein ganzes Leben

sei dir ergeben,

bis man mich einsten legt ins Grab hinein.

Nina Kunz

Can you please tell me how I should live?

An input to the cantata “Dearest Immanuel, Duke of the Pious”

Preliminary remark: I am not an expert when it comes to classical music. That’s why I didn’t approach this text with knowledge, but with joyful naivety. I listened to the piece over and over again and read the lines four, five, six, seven times.

I am almost certainly not in a position to penetrate every layer of this work of art. But in my understanding, this cantata is about the joy that with Jesus there is now a savior on earth to whom we can align our inner compass.

This inspired me to think about the desire for safety, security and direction in an overwhelming world.

My input is as follows:

It happens again and again that I lie awake at night. One reason for this is that it’s been dripping into my house for months. The roofer has been there three times, but he just can’t find the hole between the tiles that must be there. So when it rains, it drips into our attic and unfortunately my room is directly under the place where the water collects.

That sounds unspectacular, I know.

But drops can get surprisingly loud when they fall two and a half meters. Tack. Tack. Tack. The sound is now driving me half crazy.

And then there’s a second reason why I often can’t sleep. And that has to do with the fact that I tend to think about big and small questions in the dark; and these questions can get so big in my head that I can hardly believe that there is room for so much brooding in a prefrontal cortex – or wherever the brooding happens.

Only in the last week, for example, have I asked myself the following questions in the dark: Am I happy? Am I happy as a writer or should I retrain and become a social worker? Should I grow old in Zurich or in Berlin? Do I want to become a mother or is it possible that I really don’t want to have children? Will I regret it if I don’t have children? Should I get vaccinated against human papillomavirus? Do I want to focus my life on romantic relationships or on friendships? And is it still legitimate to think about personal happiness in our crisis-ridden world?

When I lie awake and think like this, it often happens that I feel stupid or bad. I feel stupid because I tend to think so much about the question “How do I want to live?” from time to time that I forget to simply live a little. And I feel bad because I basically know that it’s a huge privilege to have so much autonomy and to be able to choose something for myself from such a wide range of life models.

At these times, I almost always think of my grandmother. Because she always tells me that as a young woman she wanted to study medicine and become a doctor. That was her dream. But unfortunately, she was told that girls were not suitable for this career. So she became a lab technician.

What’s more, as she tells me, she was also expected to get married, have children and do the housework. She didn’t have half as much freedom as I did. So I don’t want to complain. I’m aware of how outrageously good I have it.

So what I want to say is: when I lie awake at night, I often ask myself why – despite all these freedoms and privileges that the generations before me have fought for – I sometimes feel so bad. Why there is this pinching in my stomach and this tingling in my fingers and this helplessness and this restlessness. And to be honest, I don’t know if I have the most appropriate, the most precise words for it yet. But I believe that this feeling has a lot to do with the fact that I expect myself to lead the best life possible. I don’t want, and this is the most important thing, to waste my limited time on earth.

I don’t know where I got the idea that you can waste your time at all, or what exactly I mean by “wasting time”. But I think that, among other things, I grew up with the imperative that you should get the best out of yourself and your talents. Otherwise you have failed. And sometimes, to put it bluntly, I feel a kind of compulsion to create myself as a great individual. And that creates pressure.

I also read from the British journalist Pandora Sykes that we now live in a world in which we are expected to know ourselves so well that we are able to make the best possible decisions that will take us further along the path to an optimal life. And I read the following sentence by sociologist Eva Illouz: “Happiness in our times is seen as a state of mind that can be brought about at will, as a result of mobilizing our inner strength and our ‘true self’.”

In any case, I often lie awake at night because, on the one hand, these freedoms – in terms of life plans, ideologies and hobbies – overwhelm me. And on the other hand, I lie awake because this self-awareness doesn’t really work: I don’t always know what I should want. I don’t always know what is good for me or what I will and won’t regret in the future.

Or to put it another way: what has been bothering me for a long time because of all these things is this great fear of making the wrong decision in life. I fear almost nothing more than taking a wrong turn and ending up in a dead end. I’m afraid of not doing “it” right, and by “it” I mean: life.

When I’m lying there and it’s midnight or half past twelve, I sometimes feel this deep desire for someone to tell me what’s right and what’s wrong. I don’t imagine a prophetess or an angel. I rather imagine that there is something like a voice inside me that gives me advice. It tells me what is sensible and what is not, what is cool and what is not, what is correct and what I should rather not do.

And yes, when I think about it like that, I feel really stupid again. Because – as I said – I have all this freedom and then I wish that someone would come along and lay down rules for me. Is that still possible?

The only thing I find comforting is that I am obviously not alone in this wish. Because at least the British author and actress Phoebe Waller-Bridge wrote a monologue in her play “Fleabag”, about a disoriented woman in her thirties, which became world-famous when the series was made into a film.

In this scene, which incidentally takes place in a church, the protagonist says: “I want someone to tell me what to eat. What I should like, hate, what I should be angry about, what I should listen to, what bands I should like, what I should buy tickets for, what I should joke about, what I shouldn’t joke about.”

When I’m still lying awake at this point, I sometimes think – and watch out, now the mental leaps are getting even bigger – about the psychologist Barry Schwartz. He doesn’t help you fall asleep. But he coined a term that keeps me very busy. The term is called the “paradox of choice” and Schwartz means that there is often so much abundance in our Western societies that it becomes nonsensical. In my everyday life, for example, I can choose between (what feels like) 75 types of muesli and 1943 Netflix series. And this huge choice doesn’t make me feel freer, but – and this is the paradox – more restricted.

So maybe, I think, my overwhelm with choices also has to do with living in a weird stage of capitalism and having to choose between so many things and books and Adidas pants and Apple Plus and SRF and HBO and Disney and Paramount series and insurance plans and vacations and window cleaner brands all the time that I’m constantly a little dizzy and forget that lots of options doesn’t mean the same thing as freedom – and then I have no energy left to think about how I actually want to live anyway.

But as I said, by the time I think these thoughts, it’s really late, my right arm has fallen asleep and my neck is twinging because I’m lying there in a strange position.

It can – and unfortunately this is no joke – happen that I even exceed this point, and then I start to think about things like the concept of freedom in and of itself – and this is generally not an easy thing to do, but at three in the morning it’s really not the best idea.

Usually the first thing that comes to mind is Jean-Paul Sartre and I think, for example, that I always found it comforting what Sartre said about being human. Because if I’m not mistaken, Sartre said that there is no predetermined purpose for human existence and that is what distinguishes us – for example – from a hammer.

That may sound a little abstruse, but I think he understood it to mean the following: When you make a hammer, you do so with the idea that you need a tool to hammer a nail into the wall, for example. We humans, on the other hand, do not have this purpose. Every day – with every action, every decision – we have to define for ourselves what it means to be human. And this is precisely where existential freedom lies, which is both a burden and a gift.

And yes: when I think such thoughts, I’m usually already a bit sleepy or in a state that is akin to hallucinating. But I still feel reasonably comfortable, because now at the latest I feel that my excessive demands with decisions and life in general are legitimate. After all, if we have to decide for ourselves every day what it means to be human and what the meaning of life is for us, then that is simply a lot to ask and it seems nothing but logical to me that I sometimes shudder and freeze because of this responsibility.

When I’m lying there like this, I also think that perhaps I don’t need a prophetess or a voice to guide my inner compass. Although – of course I’m not sure. But I just wonder whether doubt itself can also provide a kind of direction.

Because the eternal questions have been with me for a long time. Brooding is like my most loyal companion. And the rattling in my head makes me keep moving and cultivate a kind of vigilance. And there’s something nice about that.

In any case, that’s when I hear the birds chirping at the latest.

But maybe I just fell asleep.

This text has been translated with DeepL (www.deepl.com).