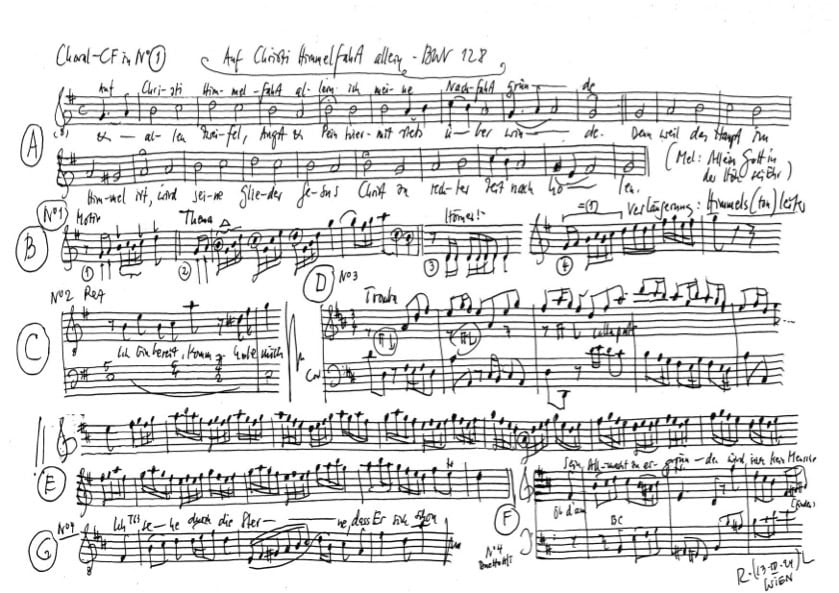

Auf Christi Himmelfahrt allein

BWV 128 // for Ascension

(On Christ’s ascent to heaven alone) for alto, tenor and bass, vocal ensemble, oboe I+II, oboe da caccia, trumpet, horn I+II, strings and basso continuo

Would you like to enjoy our videos ad-free? Subscribe to YouTube Premium now...

Workshop

Reflective lecture

Choir

Soprano

Maria Deger, Linda Loosli, Simone Schwark, Susanne Seitter, Baiba Urka, Ulla Westvik

Alto

Antonia Frey, Francisca Näf, Simon Savoy, Lea Scherer, Lisa Weiss

Tenor

Rodrigo Carreto, Clemens Flämig, Tiago Oliveira, Christian Rathgeber

Bass

Fabrice Hayoz, Serafin Heusser, Israel Martins, Julian Redlin, Tobias Wicky

Orchestra

Conductor & harpsichord

Rudolf Lutz

Violin

Éva Borhi, Cecilie Valter, Ildikó Sajgó, Péter Barczi, Christine Baumann, Petra Melicharek

Viola

Corina Golomoz, Matthias Jäggi, Anne Sophie van Riel

Violoncello

Maya Amrein, Daniel Rosin

Violone

Guisella Massa

Oboe

Katharina Arfken, Clara Espinosa Encinas

Oboe da caccia

Philipp Wagner

Bassoon

Gilat Rotkop

Horn

Stephan Katte, Thomas Friedlaender

Trumpet

Jaroslav Rouček

Harpsichord

Thomas Leininger

Organ

Nicola Cumer

Musical director & conductor

Rudolf Lutz

Workshop

Participants

Rudolf Lutz, Pfr. Niklaus Peter

Reflective lecture

Speaker

Michael Köhlmeier

Recording & editing

Recording date

26/04/2024

Recording location

Trogen AR (Switzerland) // Evang. Kirche

Sound engineer

Stefan Ritzenthaler

Producer

Meinrad Keel

Executive producer

Johannes Widmer

Production

GALLUS MEDIA AG, Schweiz

Producer

J.S. Bach-Stiftung, St. Gallen, Schweiz

Librettist

First performance

10 May 1725 – Leipzig

Text sources

C. M. von Ziegler (published 1728); movement 1: E. Sonnemann (1661, based on J. Wegelin 1636); movement 5: M. Avenarius (1673)

Libretto

1. Chor

Auf Christi Himmelfahrt allein

ich meine Nachfahrt gründe

und allen Zweifel, Angst und Pein

hiermit stets überwinde;

denn weil das Haupt im Himmel ist,

wird seine Glieder Jesus Christ

zu rechter Zeit nachholen.

2. Rezitativ — Tenor

Ich bin bereit, komm, hole mich!

Hier in der Welt

ist Jammer, Angst und Pein;

hingegen dort in Salems Zelt,

werd ich verkläret sein.

Da seh ich Gott von Angesicht zu Angesicht,

wie mir sein heilig Wort verspricht.

3. Arie — Bass

Auf, auf, mit hellem Schall

verkündigt überall:

Mein Jesus sitzt zur Rechten!

Wer sucht mich anzufechten?

Ist er von mir genommen,

ich werd einst dahin kommen,

wo mein Erlöser lebt.

Mein Augen werden ihn in größter Klarheit schauen.

O könnt ich im voraus mir eine Hütte bauen!

Wohin? Vergebner Wunsch!

Er wohnet nicht auf Berg und Tal,

sein Allmacht zeigt sich überall,

so schweig, verwegner Mund,

und suche nicht dieselbe zu ergründen!

4. Arie — Alt, Tenor

Sein Allmacht zu ergründen,

wird sich kein Mensche nden,

mein Mund verstummt und schweigt.

Ich sehe durch die Sterne,

daß er sich schon von ferne

zur Rechten Gottes zeigt.

5. Choral

Alsdenn so wirst du mich

zu deiner Rechten stellen

und mir als deinem Kind

ein gnädig Urteil fällen,

mich bringen zu der Lust,

wo deine Herrlichkeit

ich werde schauen an

in alle Ewigkeit.

Michael Köhlmeier

Ladies and gentlemen

I would like to tell you about my mother. For my mum, the terms “resurrection” or “ascension” were not something abstract, but a very tangible lifeblood. And when I have finished my story, you will know what I mean by that.

My mum’s name was Paula. She grew up in Coburg in Franconia, in Germany, which is in the north of Bavaria. She lived there. And she had a best friend, Marianne. Marianne was from Nuremberg, but she went to a nursing school in Coburg. And she loved being in Coburg, in this beautiful town – I don’t know if you know Coburg – with a medieval centre and at the same time an English flair, because the people of Coburg are related to the English royal family. With a wonderful Veste (fortress), which incidentally is spelt with a V, like a stone ship stranded on a mountain, with a beautiful courtyard garden where you can go for a walk. And my best friend Marianne and my mother were Catholic in this Protestant town of Coburg. My mum always said that she grew up in the Catholic diaspora. And they were very, very fun-loving women, but at the same time they were very God-fearing. They combined their love of life with their fear of God by getting on their bikes every chance they got and travelling from Coburg to Vierzehnheiligen – to this wonderful baroque church. And there they prayed, after first laughing hard. And they prayed that they would both get a good husband and be able to start a good family. That’s a good reason to pray.

My mum had a cousin called Karl. And my mum thought Karl would be a good match for Marianne. He was a Stiller, a very handsome man – I’ve seen photos of him – a very good-looking young man, very quiet and introverted, wrote poetry and loved Rilke. My mother thought he would be a good match for the down-to-earth Marianne, and she brought the two of them together and it worked right away. The two of them immediately fell – I’m not going to use this word too often – madly in love. But they fell madly in love. You will also see in the course of the story that this word is appropriate.

“Let’s not beat about the bush,” they said to each other, or Marianne said it, she was the down-to-earth one. “We’ll start as we should, we’ll get engaged, then we’ll get married, then we’ll start a family.” And she said to my mum: “You’ll find the right one too.” And there were a few people who would be suitable for my mum. But to be considered and to be madly in love – you want to be able to play the piano at that distance. And that’s why they often travelled back to Vierzehnheiligen. The two of them.

And then war broke out. And Karl was drafted into the war. Now they had yet another reason to pray in Vierzehnheiligen. Namely, that he would come back from the war in good health and that Paula would also meet a good man.

And one day the two women, Paula and Marianne, were walking through the courtyard garden up to the Veste, pushing their bicycles, because that was their greatest pleasure, riding their bicycles down the path from the Veste and not pedalling until they reached the market square. And as they were walking along on their bikes, two soldiers came to meet them. My mum knew one of them, he was also Catholic, in the diaspora. It was relatively well organised in Coburg back then, people knew each other. She didn’t know the other one. The two soldiers were very cheerful, very polite and said: “Can we help you? Can we push the bikes?” And the other one introduced himself. Very, very politely. His name was Alois, he said, but he was called Wiese. He comes from western Austria, from Vorarlberg, and there Wiese is an abbreviation for Alois. I can tell you straight away: he will become my father. In those days, women, young women, were told: When you meet soldiers, give them your address. So that you can write them letters to the front, so they won’t be so lonely. And they exchanged addresses. The Coburg man gave Marianne the address – she wasn’t very interested because she already had one. But Wiese got Paula’s address and the two of them wrote about 100 letters to each other. To the front and back.

Then they met a second time in Coburg. Furlough again. On the first furlough, my father went with his friend to Coburg because it would have been too far to Vorarlberg. Then they met up a third time. Each time for just one day. And the fourth time they got married. They got engaged by letter and I’m getting ahead of myself – this marriage was very happy and very respectful.

And then he disappeared again. And she didn’t know where he was, didn’t receive any more letters from him. He was gone. She could imagine that he had fallen, like everyone else who came into question – they all fell … And she waited. Then another worry came along. Her younger brother, the youngest, was only 15 and was also drafted into the war. There were now several reasons to go to Vierzehnheiligen, by bike, and pray. The boy, Gerhard, came back from the war happy. The only thing he experienced was that his glasses were broken.

And then one day a man came to the door and said: “Karl died of typhoid in British captivity.” This man said that Marianne was staying with my mum or simply because he couldn’t go to Nuremberg. Nuremberg no longer existed. And my mother just thought: “What will happen to Marianne when she finds out?”

A few days later, Marianne stood in front of the door in a black dress. Very serious. And said to my mum: “Are you going to Nuremberg with me?” She had an opportunity with several people. Everything was disintegrating, the cities had been bombed, the war was over. “I want to look for my parents.” And my mother went with her and thought to herself: “If she doesn’t start talking about Karl, then I have so much respect that I won’t do it either. Because she will speak when she has the strength to do so. My job for the time being is to be with her.”

And they came to Nuremberg and Marianne didn’t even find the street where she grew up. Nuremberg was over 90% destroyed. The old castle at the top was a pile of rubble. The whole city was a pile of rubble. The people of Nuremberg called their city the “Adolf Hitler Mountains”. They hid somewhere for the night. It was more than likely that Marianne’s parents, her brothers and her grandparents, who lived in the house, had not survived the bombing. And that night Marianne said to my mother: “I couldn’t bear it if I didn’t know that I would soon be back with Karl.” And my mother understood that Marianne, who believed in an afterlife and a reunion in the hereafter, wanted to do something to herself. And she tells her and Marianne says: “What are you talking about? What am I supposed to do to myself? Karl and I are going to get married, we’re going to have children and a family.” And then my mum knew: she doesn’t know yet. And she didn’t have the heart to tell her in this situation, when she thought her family was no longer alive either. – Incidentally, her family left Nuremberg in good time.

Marianne, who I was always allowed to call Aunt Marianne until her death, was an incredibly cheerful person. Whenever she visited us, it was always a day full of laughter. Aunt Marianne started a medical degree, studied medicine, joined a convent and went to East Africa to heal and help leprosy sufferers there. Sometimes she visited us in Austria, where she talked about Africa and told us about Karl again and again.

My mother was in Munich at the end of the war and never heard from her husband, from Wiese. She was in a home for young girls near Munich, where she looked after these young girls. And at some point she thought to herself: “Well, I know where he comes from. From Hard in Vorarlberg.” She looked at the map and finally thought: “Well, it’s worth a try! I’ll pack my rucksack and put ‘Faust’ in it.” – She had had the book all her life, it was soaked. My father and my mother used to throw quotes at each other, he Wilhelm Busch, she Faust. – And then she set off on foot from Munich to Hard. Incidentally, she liked to talk about the time immediately after the war. She even once said that she had never been happier in her entire life than when she was balancing on the tops of the walls of the destroyed houses. – There was simply nothing left to lose, only to gain. – And she went all the way to Hard on foot and thought to herself: “Well, Hard isn’t that big. I’ll just stand by the village fountain and see what happens.” And then she saw him coming along. – That was still a time when Germans weren’t allowed into Austria and Austrians weren’t allowed into Germany, or had just been abolished. – And she goes up to him and says: “Wiese, do you remember me? I’m your wife.”

And then they moved in together, looked for accommodation, looked for flats. First my sister was born, then I was born. And then she was pregnant for the third time. And when she gave birth, lightning struck. A vein burst in my mother’s head and she was paralysed on her left side. And she, who loved nothing more than cycling, walking and hiking, could no longer do any of that. When she went to church with my father on Sunday, she couldn’t even get up from the pew to take communion. My father would pick her up and carry her to the front. And back again. She never recovered from that for the rest of her life. She had a brace on her left leg, her left hand was clawed and later she was in a wheelchair.

And every four years, my father and mother travelled to Lourdes. In the summer. My birthday is in October. My mum said to me: “Watch out” – every time – “we’ll be back in three weeks, then it’ll be the end of July. You have to give me a little time to get used to it, but in October, on your birthday, I promise you, we’ll both go up the Hohe Kugel – 1664 metres above sea level. – And she came back from Lourdes. We were waiting by the window and saw my father carrying my mother out of the car. We thought to ourselves: “Well, okay, it won’t be that quick.” But she hadn’t recovered and she was still healthy. Because she came back from Lourdes as the happiest person, with a very pragmatic attitude. She said: “There’s always at least one person there who’s worse off.” That’s not cynicism. It’s not cynicism. If you think about it for a long time, you realise it’s not cynicism. My father, another tough guy, used to say: “We’re going to the Republic of Cripples.” That wasn’t cynicism either. But you have to understand that. When you hear it from the outside, you don’t understand it. For two years, they were fuelled by the memory of Lourdes, and for the next two years they were fuelled by the anticipation of Lourdes. They came back from Lourdes with the whole boot full of Lourdes water. They took extra bottles with them. Towards the end you had to dilute them with high spring water from the Hohe Kugel. But it works if you leave it to stand for a while, then it infuses like sourdough. My mum knew that very well. And that’s how her life was. That sounds so sad, but it’s not. My mum wasn’t bitter at all. Not at all. Neither was my father. They were both actually very funny people by nature. My mum, above all, she could laugh so loudly. She could also swear so loudly that you could hear it three houses away. But she could also laugh so loudly that you could hear it three houses away, and everyone who heard her laughing couldn’t help but join in. And it was similar when Marianne came from Africa. There was always a lot of laughter then. Or especially when my uncle Gerhard came. The youngest brother. The most charming person I’ve ever met. What a laugh we had. What we laughed there! And whenever we laughed a lot, my mum would cry afterwards. I asked her: “Why are you crying after we’ve laughed so much?” And she gave the only valid answer: “So that I can be even with myself.” – That is concrete “resurrection” and concrete “ascension”. I was there when she closed her eyes. And for her, of course, it was an ascension. Because she always believed that it would be better over there.

Thank you very much.

This text has been translated with DeepL (www.deepl.com).