Schau, lieber Gott, wie meine Feind

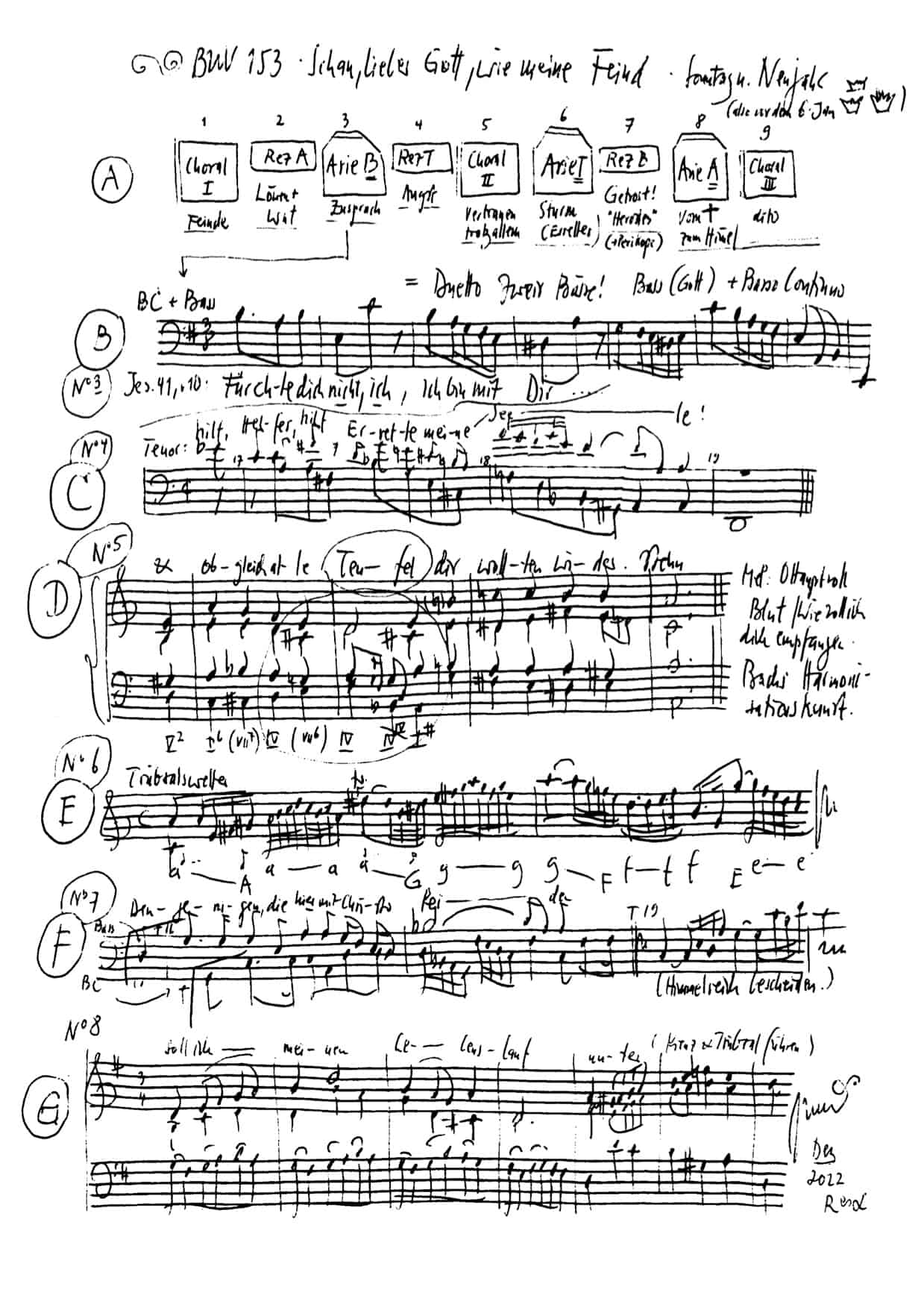

BWV 153 // For the Sunday after New Year’s Day

(Behold, dear God, how all my foes) for alto, tenor and bass, vocal ensemble, strings and basso continuo

Would you like to enjoy our videos ad-free? Subscribe to YouTube Premium now...

Workshop

Reflective lecture

Choir

Soprano

Cornelia Fahrion, Linda Loosli, Susanne Seitter, Noëmi Sohn Nad, Noëmi Tran-Rediger, Alexa Vogel

Alto

Laura Binggeli, Stefan Kahle, Francisca Näf, Alexandra Rawohl, Lea Scherer

Tenor

Marcel Fässler, Achim Glatz, Tobias Mäthger, Joël Morand

Bass

Serafin Heusser, Valentin Parli, Philippe Rayot, Oliver Rudin, William Wood

Orchestra

Conductor

Rudolf Lutz

Violin

Eva Borhi, Lenka Torgersen, Christine Baumann, Petra Melicharek, Ildikó Sajgó, Cecilie Valter

Viola

Martina Bischof, Peter Barczi, Matthias Jäggi

Violoncello

Maya Amrein, Daniel Rosin

Violone

Markus Bernhard

Bassoon

Susann Landert

Harpsichord

Thomas Leininger

Organ

Nicola Cumer

Musical director & conductor

Rudolf Lutz

Workshop

Participants

Rudolf Lutz, Pfr. Niklaus Peter

Reflective lecture

Speaker

Usama Al Shahmani

Recording & editing

Recording date

13/01/2023

Recording location

Trogen AR (Switzerland) // Evangelische Kirche

Sound engineer

Stefan Ritzenthaler

Producer

Meinrad Keel

Executive producer

Johannes Widmer

Production

GALLUS MEDIA AG, Schweiz

Producer

J.S. Bach-Stiftung, St. Gallen, Schweiz

Librettist

First performance

30 January 1735, Leipzig

Text

Martin Luther (movements 1 and 5), unknown source (movements 2–4)

Libretto

1. Choral

Schau, lieber Gott, wie meine Feind,

damit ich stets muß kämpfen,

so listig und so mächtig seind,

daß sie mich leichtlich dämpfen!

Herr, wo mich deine Gnad nicht hält,

so kann der Teufel, Fleisch und Welt

mich leicht in Unglück stürzen.

2. Rezitativ — Alt

Mein liebster Gott, ach laß dichs doch erbarmen,

ach hilf doch, hilf mir Armen!

Ich wohne hier bei lauter Löwen und bei Drachen,

und diese wollen mir durch Wut und Grimmigkeit

in kurzer Zeit

den Garaus völlig machen.

3. Arioso — Bass

«Fürchte dich nicht, ich bin mit dir. Weiche nicht, ich bin dein Gott; ich stärke dich, ich helfe dir auch durch die rechte Hand meiner Gerechtigkeit.»

4. Rezitativ — Tenor

Du sprichst zwar, lieber Gott, zu meiner Seelen Ruh

mir einen Trost in meinem Leiden zu.

Ach, aber meine Plage

vergrößert sich von Tag zu Tage,

denn meiner Feinde sind so viel,

mein Leben ist ihr Ziel,

ihr Bogen wird auf mich gespannt,

sie richten ihre Pfeile zum Verderben,

ich soll von ihren Händen sterben;

Gott! meine Not ist dir bekannt,

die ganze Welt wird mir zur Marterhöhle;

hilf, Helfer, hilf! errette meine Seele!

5. Choral

Und ob gleich alle Teufel

dir wollten widerstehn,

so wird doch ohne Zweifel

Gott nicht zurücke gehn;

was er ihm fürgenommen

und was er haben will,

das muß doch endlich kommen

zu seinem Zweck und Ziel.

6. Arie — Tenor

Stürmt nur, stürmt, ihr Trübsalswetter,

wallt, ihr Fluten, auf mich los!

Schlagt, ihr Unglücksflammen,

über mich zusammen,

stört, ihr Feinde, meine Ruh,

spricht mir doch Gott tröstlich zu:

Ich bin dein Hort und Erretter.

7. Rezitativ — Bass

Getrost! mein Herz,

erdulde deinen Schmerz,

laß dich dein Kreuz nicht unterdrücken!

Gott wird dich schon

zu rechter Zeit erquicken;

muß doch sein lieber Sohn,

dein Jesus, in noch zarten Jahren

viel größre Not erfahren,

da ihm der Wüterich Herodes

die äußerste Gefahr des Todes

mit mörderischen Fäusten droht!

Kaum kömmt er auf die Erden,

so muß er schon ein Flüchtling werden!

Wohlan, mit Jesu tröste dich,

und glaube festiglich:

Denjenigen, die hier mit Christo leiden,

will er das Himmelreich bescheiden.

8. Arie — Alt

Soll ich meinen Lebenslauf

unter Kreuz und Trübsal führen,

hört es doch im Himmel auf.

Da ist lauter Jubilieren,

daselbsten verwechselt mein Jesus das Leiden

mit seliger Wonne, mit ewigen Freuden.

9. Choral

1.

Drum will ich, weil ich lebe noch,

das Kreuz dir fröhlich tragen nach;

mein Gott, mach mich darzu bereit,

es dient zum Besten allezeit!

2.

Hilf mir mein Sach recht greifen an,

daß ich mein Lauf vollenden kann,

hilf mir auch zwingen Fleisch und Blut,

für Sünd und Schanden mich behüt!

3.

Erhalt mein Herz im Glauben rein,

so leb und sterb ich dir allein;

Jesu, mein Trost, hör mein Begier,

o mein Heiland, wär ich bei dir!

The language after the flight

Usama Al Shahmani

“Life in Iraq has made us complicated people. You have to understand that I don’t do this on purpose. Sometimes I feel like I lost half of my language in the war and the other half contains words I don’t like. But I always fail to get them out of me. How often I try to throw them away, but they quickly return to me as if I were playing fetch with a well-behaved dog,” my father told me on the phone when I asked him a few years ago to speak differently to my mother and to be patient with her. After the phone call, I was distraught. “Wars shorten language and make it sullen,” I told myself. I thought of the conversations we had had while I was studying in Iraq: “In war, language breathes Russ. The word loses its shine and its beauty. In war, words fall too, not just people, and the longer the war lasts, the bigger the graveyard of fallen words becomes.” In times of war, language does something other than what it is actually there for. It no longer opens our world but limits it, it destroys bridges instead of building them, and it is able to build walls between us. Many words were torn out of their everydayness during the war.

During the war years in Iraq, many words were transformed into their semantic opposite. Language had gone from being a medium of communication to an instrument of division. Suddenly people started talking as if they wanted to build moats and fences between each other. New words appeared in the streets, in the houses, in schools and gardens. Huge, monstrous words and unbearable phrases descended on everyday life and haunted people all the way to their bedrooms. Conversations took on sharp features, even the language of the body became painful, and there are a number of words where to this day I do not understand how their meaning could transform – for example, the word “cinema”. Suddenly, “cinema” no longer meant just “cinematography ” or referred to the place where films are shown, but now referred to the condition of man in war. This implied that life in war was not real but imagined – an illusion, something that did not exist. Man was no more than a carrier of his role, a tool of his language, which had been imposed on him and which he had to obey. To this day, many Iraqis use the word “cinema” to describe a helpless person. Yes, language does not forget what man experiences. Wars and enemies bring with them certain languages that flow directly into the vessel of a society. For Iraqis, it is still impossible today to separate the language of war from their everyday one.

In the Gilgamesh epic, the Sumerian king Gilgamesh mourns the death of his friend Enkidu. Gilgamesh finds nothing in language to comfort him. He leaves everything behind and goes in search of something in nature that could broaden his horizons. Finally, he writes a poem that is still considered one of the greatest epics in literary history. With it, he created the language of the Sumerians and thus a vessel from and for language – completely new. What has remained of the Sumerian heritage? What does the vessel in which I keep my languages look like?

Am I the vessel and the language is the content or is it the other way round? Why is language not always enough to describe a moment, to form the image of a perception or to put anger on paper? The Sumerians used language and music to calm the angry Euphrates when it flooded the surrounding landscapes and villages. They celebrated a great feast on its banks, lit candles and recited poetry – until the women sang at dawn for the river and the flood victims.

In silence, language leaves speech. It becomes invisible. My student friends and I belong to a whole generation of invisible words. We did not speak in the language of war, but it spoke through us. Silence became our everyday condition, and we remained silent even in those moments when we should have spoken. Those who spoke had to reckon with grave consequences, and those who remained silent had to learn to bear the pain of the unspoken. This necessary renunciation of the word certainly damaged our vessels. I still suffer from the unspoken words today. I feel them, like the little stone that involuntarily jumps into your shoe and disturbs you when you walk. I still remember the beginning of the Second Gulf War on 15 January 1991. I was in Baghdad with my friends Ali and Marwan. We were leaving the flat. It was a wintry but clear night. The round full moon hung in the sky like a big eye watching the irritated people on the street. They were like a hive of bees from a destroyed hive: they were searching for a common language that could tell them why this war had been announced so unexpectedly and so coldly. Their vessels for and of language were not empty, but the dictatorship gradually ate up all the time-honoured words. Instead of words, something strange grew on their tongues. No one was able to mouth the hope of peace, for example. Fear nested on their tongues.

My friends and I went to a park near the university and tried to talk to each other. We cried because we failed at it, because the words came burnt from our lips. We realised that a winter of veiled sun was ahead of us, that the Tigris would tear the sails of its boats and that in the forest the echoes would fall silent. Silently we returned before the sun rose.

The hope was small, but it was there, and we knew that this lost word would one day be found again. The Arabic word for “hope” is “amal”, and if you put the last two letters at the beginning, it becomes the word “alam” – it means “pain”. Why did the Arabic language carve “hope” and “pain” from the same stem?

“If you feel you can’t reconcile with the world, then you have to learn a foreign language,” said our professor who taught us linguistics at the university in Baghdad. And that is exactly what I have been doing in Switzerland for twenty years. Even as a student, I laughed inside when someone claimed to know a language. I see myself more as a child crawling and babbling on the beach of languages, searching for the moment that it doesn’t even know exists yet.

“What is exile doing to your Arabic vessel?” my old friend Marwan asked me when I saw him again in Baghdad in 2016, twenty-five years after my escape.

I did not give him an answer because I did not know how to answer his question. I did not manage to get the words stuck in my throat out. I should have told him how the exile language and the mother tongue run in two parallel, straight lines and how these lines never cross or meet, how one language learns from the other and looks for opportunities to converge. After twenty years in exile, I know what to do when the mother tongue line gets shorter. I learned to listen to the whisper of my mother tongue and to turn my back on the roar of war. And I learned in exile to search for synonyms of many words I only knew in Arabic.

A few weeks ago I came back to Marwan’s question, I wrote it down on a piece of paper and put it on the desk in my flat in Frauenfeld. And instead of answering Marwan’s question, I wrote him a poem:

Do you remember

when the war broke out,

you and I sat on the floor

the carpet in Baghdad’s sky was torn apart

the wind was beating

it carried away its fabric

a rocket fell on the old wooden bridge

over the Tigris,

it broke off its ribs

language trembled,

many words hid,

a few verbs, nouns and ideas threw themselves

themselves into the river,

King Gilgamesh walked out of the museum

into the garden,

barefoot, he stood before the great chestnut tree,

lifting his head to the sky,

in vain he searched for the torn fabric,

Birds flew up from the tree,

Gilgamesh cried out loudly,

his cry entered the kitchens, bedrooms,

schoolhouses,

the small chambers of Baghdad’s popular theatre,

where actors changed their clothes,

into old alleys,

where books were displayed for sale

for sale on the street,

birthing rooms in the great hospital by the river,

where you and I were born,

even into studios his cry invaded,

in so-called Allah houses, and in the art street,

where paintings were sold,

whose artists remained anonymous,

like you and me, my friend.

Then that scream froze,

abruptly became thin glass,

that shattered in all those rooms,

mingled with the sand,

approached the Tigris, and tried to find the traces

of verbs, nouns and ideas.

This text has been translated with DeepL (www.deepl.com).