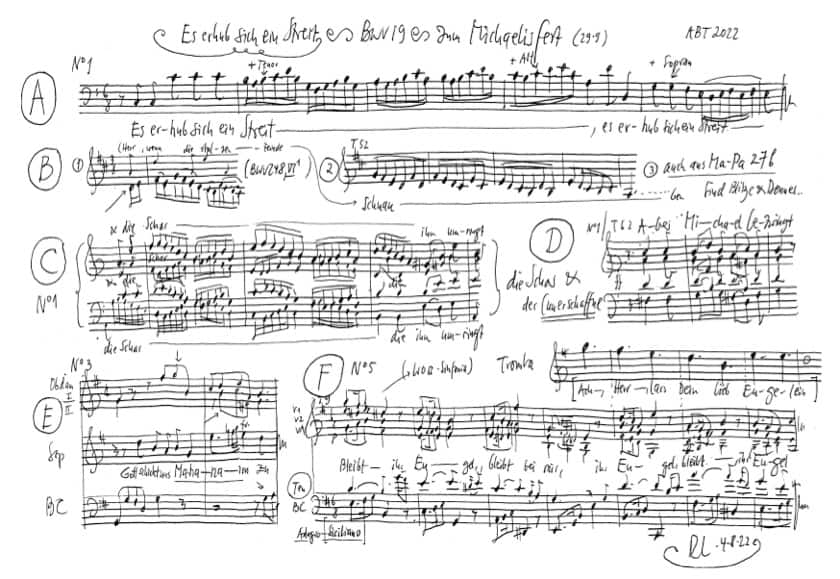

Es erhub sich ein Streit

BWV 019 // Feast of St Michael and All Angels

(There arose a great strife) for soprano, alto, tenor and bass; vocal ensemble, oboe and oboe d’amore I+II, taille, trumpet I-III, timpani, strings and basso continuo

Place of composition in the church year

Pericopes for Sunday

Pericopes are the biblical readings for each Sunday and feast day of the liturgical year, for which J. S. Bach composed cantatas. More information on pericopes. Further information on lectionaries.

Wer unter dem Schirm des Höchsten sitzt und unter dem Schatten des Allmächtigen bleibt, der spricht zu dem Herrn: «Meine Zuversicht und meine Burg, mein Gott, auf den ich hoffe.»

Und es erhob sich ein Streit im Himmel: Michael und seine Engel stritten mit dem Drachen; und der Drache stritt und seine Engel, und siegten nicht, auch ward ihre Stätte nicht mehr gefunden im Himmel. Und es ward ausgeworfen der grosse Drache, die alte Schlange, die da heisst der Teufel und Satanas, der die ganze Welt verführt, und ward geworfen auf die Erde, und seine Engel wurden auch dahin geworfen. Und ich hörte eine grosse Stimme, die sprach im Himmel: «Nun ist das Heil und die Kraft und das Reich unseres Gottes geworden und die Macht seines Christus, weil der Verkläger unserer Brüder verworfen ist, der sie verklagte Tag und Nacht vor Gott. Und sie haben ihn überwunden durch des Lammes Blut und durch das Wort ihres Zeugnisses und haben ihr Leben nicht geliebt bis an den Tod. Darum freuet euch, ihr Himmel und die darin wohnen! Weh denen, die auf Erden wohnen und auf dem Meer! Denn der Teufel kommt zu euch hinab und hat einen grossen Zorn und weiss, dass er wenig Zeit hat.»

Zu derselben Stunde traten die Jünger zu Jesu und sprachen: «Wer ist doch der Grösste im Himmelreich?» Jesus rief ein Kind zu sich und stellte es mitten unter sie und sprach: «Wahrlich, ich sage euch: Es sei denn, dass ihr umkehret und werdet wie die Kinder, so werdet ihr nicht ins Himmelreich kommen. Wer nun sich selbst erniedrigt wie dies Kind, der ist der Grösste im Himmelreich. Und wer ein solches Kind aufnimmt in meinem Namen, der nimmt mich auf. Wer aber ärgert dieser Geringsten einen, die an mich glauben, dem wäre besser, dass ein Mühlstein an seinen Hals gehängt und er ersäuft würde im Meer, da es am tiefsten ist. Weh der Welt der Ärgernisse halben! Es muss ja Ärgernis kommen; doch weh dem Menschen, durch welchen Ärgernis kommt! So aber deine Hand oder dein Fuss dich ärgert, so haue ihn ab und wirf ihn von dir. Es ist dir besser, dass du zum Leben lahm oder als ein Krüppel, denn dass du zwei Hände oder zwei Füsse habest und werdest in das ewige Feuer geworfen. Sehet zu, dass ihr nicht jemand von diesen Kleinen verachtet. Denn ich sage euch: Ihre Engel im Himmel sehen allezeit das Angesicht meines Vaters im Himmel. Denn des Menschen Sohn ist gekommen, selig zu machen, das verloren ist.»

Would you like to enjoy our videos ad-free? Subscribe to YouTube Premium now...

Workshop

Reflective lecture

Publikationen zum Werk im Shop

Choir

Soprano

Lia Andres, Guro Hjemli, Linda Loosli, Stephanie Pfeffer, Mirjam Wernli, Ulla Westvik

Alto

Laura Binggeli, Antonia Frey, Lea Pfister-Scherer, Simon Savoy, Lisa Weiss

Tenor

Clemens Flämig, Manuel Gerber, Tiago Oliveira, Sören Richter

Bass

Jan Börner, Jean-Christophe Groffe, Valentin Parli, Daniel Pérez, Tobias Wicky

Orchestra

Conductor

Rudolf Lutz

Violin

Renate Steinmann, Monika Baer, Yuko Ishikawa, Petra Melicharek, Ildikó Sajgó, Rahel Wittling, Salome Zimmermann

Viola

Susanna Hefti, Matthias Jäggi, Claire Foltzer

Violoncello

Martin Zeller, Bettina Messerschmidt

Violone

Markus Bernhard

Trumpet

Patrick Henrichs, Benedikt Neumann, Pavel Janeček

Timpani

Martin Homann

Oboe/Oboe d’amore

Andreas Helm, Thomas Meraner

Taille

Laura Alvarado

Bassoon

Susann Landert

Harpsichord

Thomas Leininger

Organ

Nicola Cumer

Musical director & conductor

Rudolf Lutz

Workshop

Participants

Rudolf Lutz, Pfr. Niklaus Peter

Reflective lecture

Speaker

Philipp Theisohn

Recording & editing

Recording date

19/08/2022

Recording location

Teufen AR (Schweiz) // Evangelische Kirche

Sound engineer

Stefan Ritzenthaler

Producer

Meinrad Keel

Executive producer

Johannes Widmer

Production

GALLUS MEDIA AG, Schweiz

Producer

J.S. Bach-Stiftung, St. Gallen, Schweiz

Librettist

First performance

29 September 1726, Leipzig

Text

Christian Friedrich Henrici (Picander, movements 1–6), unknown source (movement 7)

In-depth analysis

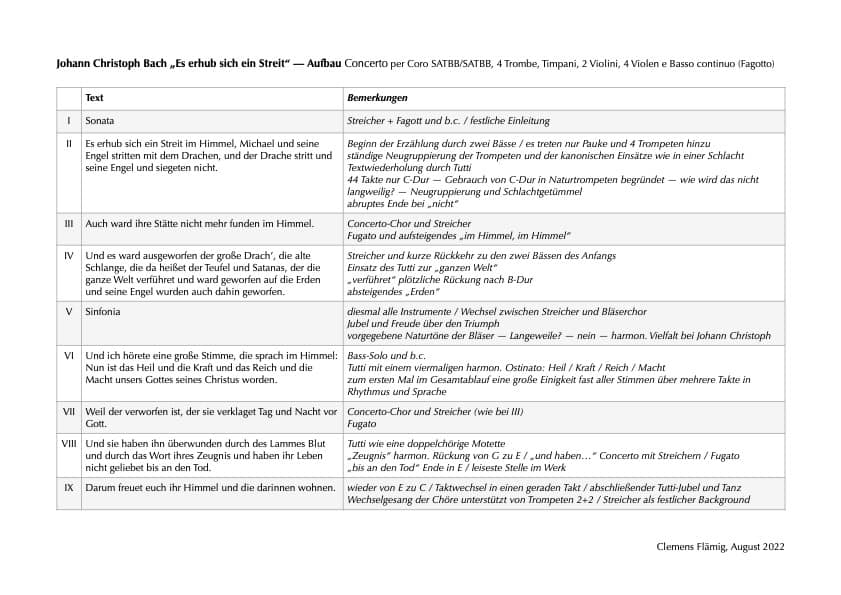

In Bach’s time, Michaelmas was one of the feast days in the liturgical year celebrated with magnificent church music. Indeed, the day’s reading from the Book of Revelation provided ample incentive for such a large-scale composition, and its description of the angels’ battle in heaven – a particularly combative chapter of salvation history – sparked the imagination of many a Baroque composer. After Bach’s uncle Johann Christoph Bach from Eisenach had already produced a 22-voice setting of “Es erhub sich ein Streit” (There arose a great strife), a work characterised by weighty chords that Johann Sebastian Bach knew and likely performed in Leipzig, the Thomaskantor set about creating his own composition for St Michael’s day in 1726, based on a libretto by Picander that was reworked by Christoph Birkmann.

Yet how uniquely Bach approached his task! Where most of his contemporaries would set the scene for battle and victory with a powerful orchestral prelude, Bach begins with an opening chorus in which the choir enters directly with a brusque fugue replete with octave leaps and breakneck coloraturas, while the instruments of the full orchestra only successively join in. Through this bold constellation, Bach portrays a brewing confrontation and the all-consuming momentum it can gain: “Es erhub sich ein Streit!” (There arose a great strife!). In fact, it is only in the middle section, after the din of the event has subsided somewhat, that the “rasende Schlange” (furious serpent) and the archangel’s victorious hosts are named as the actual adversaries – Bach’s rousing Michaelmas music is thus also a musical study of how crowds and power are manifested among humans.

Following this dramatic War in Heaven, the bass recitative enters calmer waters. Thanks to the succinct, retrospective account of Michael’s victory and the damnation of the satanic dragon, the vocalist can focus on the comforting protection of the attending angels, and thus on the main theme of the cantata.

The soprano aria, fittingly accompanied by the warm timbre of two cantabile oboes d’amore, shows that these angels are not only fighting a victorious battle, but that they can also support us in our earthly struggles. In the oft-confusing angelology of the early church, “Mahanaim” is the place east of the Jordan where Jacob encountered the angels of God, after which he settled, as it were, in the army camp of the Highest. This association explains why the setting, despite its blissful G-major tonality, is permeated by rigorous imitation and a majestic style.

The presence of the angels, however, fails to erase the disparity between the citizens of heaven and children of earth. Accordingly, the ensuing tenor accompagnato paints a drastic picture of how low sinful earthlings can fall, thereby rendering all the brighter the inexplicable miracle of heaven’s devotion to such degenerate creatures. Here, it is the seraphim of God’s court who, with their constant song of praise, embody yet another form of being in the heavenly host.

The following tenor aria delivers a highly personal interpretation of this heavenly protection. In an elegiac E-minor setting in swinging 6⁄8 time, the vocalist pleads in full awareness of his weakness: “Bleibt, ihr Engel, bleibt bei mir! Führt mich auf beiden Seiten” (Stay, ye angels, stay by me! Lead me so and stay beside me). That Bach added an instrumental chorale played on the trumpet to this heartfelt prayer (“Ach Herr, lass dein lieb Engelein” – Ah Lord, allow thine angel dear) is a stroke of artistic genius demonstrating both Bach’s mastery of form and his sensitivity as an interpreter. Indeed, it portrays nothing less than the escort at the hour of death – and thus the final battle facing every human being. Here, the victorious outcome is proclaimed in the trumpet’s muted splendour, ere the aria text counsels us to join the angels’ singing of the mighty “Holy” while we are still on earth.

With the path thus prepared, the soprano recitative encourages a nigh intimate relationship with the angels. Indeed, they are to be venerated as a corrective force for good in our lives so that, in our final hour, the angels take us on their heavenly chariot to a better world. In the closing chorale, the congregation can then join with full voice in this vision of hope. In this setting, the ninth verse of the hymn “Freu dich sehr, O meine Seele” (Rejoice greatly, o my soul) ensures every true believer a place in Elijah’s “chariot of fire”, escorted by angels to heaven, while Bach’s obbligato trumpets illuminate a promise made in Christ not only to the fathers and prophets of the Old Covenant, but to the entire ecumenical community.

Libretto

1. Chor

Es erhub sich ein Streit.

Die rasende Schlange, der höllische Drache

stürmt wider den Himmel mit wütender Rache.

Aber Michael bezwingt,

und die Schar, die ihn umringt,

stürzt des Satans Grausamkeit.

2. Rezitativ — Bass

Gottlob! der Drache liegt.

Der unerschaffne Michael

und seiner Engel Heer

hat ihn besiegt.

Dort liegt er in der Finsternis

mit Ketten angebunden,

und seine Stätte wird nicht mehr

im Himmelreich gefunden.

Wir stehen sicher und gewiß,

und wenn uns gleich sein Brüllen schrecket,

so wird doch unser Leib und Seel

mit Engeln zugedecket.

3. Arie — Sopran

Gott schickt uns Mahanaim zu;

wir stehen oder gehen,

so können wir in sichrer Ruh

vor unsern Feinden stehen.

Es lagert sich so nah als fern,

um uns der Engel unsers Herrn

mit Feuer, Roß und Wagen.

4. Rezitativ — Tenor

Was ist der schnöde Mensch, das Erdenkind?

Ein Wurm, ein armer Sünder.

Schaut, wie ihn selbst der Herr so liebgewinnt,

daß er ihn nicht zu niedrig schätzet

und ihm die Himmelskinder,

der Seraphinen Heer,

zu seiner Wacht und Gegenwehr,

zu seinem Schutze setzet.

5. Arie — Tenor

Bleibt, ihr Engel, bleibt bei mir!

Führet mich auf beiden Seiten,

daß mein Fuß nicht möge gleiten!

Aber lernt mich auch allhier

euer großes Heilig singen

und dem Höchsten Dank zu singen!

6. Rezitativ — Sopran

Laßt uns das Angesicht

der frommen Engel lieben

und sie mit unsern Sünden nicht

vertreiben oder auch betrüben.

So sein sie, wenn der Herr gebeut,

der Welt Valet zu sagen,

zu unsrer Seligkeit

auch unser Himmelswagen.

7. Choral

Laß dein Engel mit mir fahren

auf Elias Wagen rot

und mein Seele wohl bewahren,

wie Lazrum nach seinem Tod.

Laß sie ruhn in deinem Schoß,

erfüll sie mit Freud und Trost,

bis der Leib kommt aus der Erde

und mit ihr vereinigt werde.

Reflection Philipp Theisohn

The cantata that we have heard and will hear again, Bachwerkverzeichnis No. 19, takes its starting point from a very specific passage from the New Testament, namely Revelation of John 12:7, which describes the battle of the archangel Michael and his angels with the dragon, the devil, Satanas, a battle that is decided in the Bible in three verses. I quote from Luther:

And there was a battle in heaven: Michael and his angels fought with the dragon; and the dragon fought and his angels, 8 and prevailed not, neither was their place found any more in heaven. 9 And the great dragon was cast out, that old serpent, which is called the devil, and Satan, which deceiveth the whole world: and he was cast unto the earth, and his angels were cast there also.

You will hear the echo of these verses in the chorus and in the recitative; it is a re-poem of or with the Luther translation. The arias and recitatives that follow are taken in their preliminary form from the Sammlung erbaulicher Gedancken (1725) Christian Friedrich Henricis (there 434 ff.), who was presumably also responsible for the text of the cantata as a whole and probably also wrote the final chorale, which deals with the chariot of heaven, Elijah and Lazarus. So much for the philology, which need not be carried too far at this point, but which nevertheless helps us a little, because it helps to subdivide this cantata text somewhat: The chorus and first recitative are adaptations of a biblical text, followed by the interpretation – allegorical, moral, in the final chorale anagogic. In other words, fourfold scriptural meaning. But first we stay with the litteral sense, that is, with what is written. And we notice two things. Firstly, in contrast to the biblical passage, the cantata text spends considerably more time on the loser of the battle, the dragon, the darkness in which he is forged, his roar. This is not necessarily done out of empathy, even if one may assume that the poet of the cantata text knew Milton’s Paradise Lost and was also correspondingly familiar with the Luciferian fate. In the light of the cantata, of course, Satan’s continuing presence also serves to actualise it: the battle in the heavens may be far away, long before us, long after us, but the devil and his servants are down here, living with us, their voice always audible. We have to deal with it, and how we are to do so, we learn when we listen carefully.

Secondly – and this is the actual thing to talk about: Michael. A figure of light. A tremendous divine power, archangel, the ruler of all angels, he basically needs no introduction, he is simply there, defeats the dragon, that is what he does, that is what he is. The cantata, which is the Michaelmas cantata, is also subject to him, the voices are subject to him – and at the same time this figure also arouses our suspicion, as is the case with all figures of light. Why is that so? Because figures of light are subject to certain conditions of production, which are made very clear to us here. Michael, as the first recitative reminds us, is “the uncreated”, and “uncreated” he is in more ways than one. He, the most venerated of all the saints of the Church, is at the same time the only saint without a history of his own. Of course there are legends of Michael, but they do not bring us closer to the figure, they are legends of fighters and victors, they allow no empathy, no compassion. This figure has no psychology. She is “uncreated”, has neither a birthday nor a place of birth, she cannot die, not even suffer. Only win. She dazzles.

That is certainly problematic. The counter-angel, the dragon, is unmistakably incomparably closer to man in his fall, in his torture, than Michael. But what may sound scandalous at first has a truth of its own: the undeniably good is far from us, it is an abstraction, and this also applies to the event of revelation, to the struggle between the last powers in which the Michael figure is located. If we are honest, this is not a struggle that becomes accessible to us, that is human, it is not Achilles against Hector. The poet of the cantata text knows this – and that is precisely why he adopts the dry diction of Luther’s translation. “A quarrel arose” – Καὶ ἐγένετο πόλεμος ἐν τῷ οὐρανῷ – and in Greek this phrase has by no means more passion than in German. This quarrel “happens” and, even if Nietzsche is not entirely wrong in saying that God has not taken a good Greek, much is said in this impersonal verb form: after all, we think we know what a quarrel is, namely, a divisiveness, an opposition of two parties; and when we think of quarrel, our conception of it is directed entirely to the causes of this divisiveness: Conflicting claims, misunderstandings, irritability. But all that is omitted here: the quarrel between Michael and the dragon needs no justification – and only the loser develops an emotional profile. Nothing remains for the winner, Michael. And that is why the text must not end after the first recitative, but must still convey to the audience what it has in common with Michael.

What is peculiar about this text is its change of perspective. At the end of the first recitative, the “we” are still assigned a rather passive position: We are indeed frightened by the roaring dragon, but then “covered with angels”, i.e. protected from evil. But that changes now. With the beginning of the aria, a journey begins: “God sends us to Mahanaim”, it says, and this does not mean that God sends something to man, but that he sends him to a very specific place, namely to the place where Jacob meets the angels of God in Genesis 32:2; he understands that this is the “camp of God”:

כַּאֲשֶׁ֣ר רָאָ֔ם מַחֲנֵ֥ה אֱלֹהִ֖ים.

And because the army camp is called “Machaneh” in Hebrew, he names the place “Machanajim”, which is the Hebrew dual and accordingly means “two camps”. So we are sent to this place, and if at first it reads as if it is only a matter of getting there in order to be protected by the angels from then on, “standing or walking”, we must not be completely naive: “We” stand “before our enemies” in the army, “fire, horse and chariot” around us, in the midst of a battle that continues in the inner world, a battle for the soul. It has its meaning that “Machaneh” becomes “Machanajim”: because it is precisely about this doubling. Heaven and earth, but also angels and humans, each a camp, a common army. Henrici’s text reflects this: the angels protect, but they are also comrades in arms – and the doubling goes even further.

On the surface, man remains “a worm, a poor sinner” who can basically only escape the devil because God is so gracious as to send him “the seraphim’s” army for protection. However, the one whom the seraphim surround is actually Michael, the Lord of the Seraphim, that figure of whom we had just claimed that he was unapproachable, unprofiled, unbroken light. In fact, she is not, if one only walks through the cantata: The low and the high, the worm and the archangel mirror each other, complement each other. The figure of light lends man reliable protection when he sets out for the army camp and arms himself; conversely, Michael receives a vita, a profile, a history in the unprotected, always challenged, temptable. This dialectic calls the cantata and at the same time emphasises its fragility, which must be sought where history and stories come to an end, where army camps must be changed: in death.

Here one could look separately at the final chorale, which is about the escort of the chariots of the soul beyond death and about the resurrection. That is quickly understood. It seems more important to me to once again undertake the fundamental reflection of this text: Its task, as already explained, consists in the difficult undertaking of singing about a figure to whom nothing sticks, who is basically uncountable and who, moreover, even outside the events of the Revelation, in Enoch literature, i.e. in the Apocrypha, simply remains an indomitable warrior figure, without – as it is called today – a “backwound story”, untraumatised.

We have seen that the text seeks the solution by having Michael, surrounded by hosts of angels, mirror himself in the human being surrounded by hosts of angels, so that the latter gets an earthly revenant in the “other camp”. However, this by no means answers the question of where such a figure as the archangel Michael comes from in the first place, what it is needed for, what is “meant to be said” with it. I will certainly not be able to answer this question adequately at this point, but I will give a hint. An “uncreated” figure of which it is said that its function is, among other things, to soften the divine radiance so that creation can enter into contact with the Creator at all: such a figure is in fact a “light figure”, i.e. a medium. Michael does not so much appear as he allows others and other things to appear, to come to light. In the Judeo-Christian tradition, this can and will first of all be God, whom he not only represents, but whose presence Michael marks in the first place. But that is by no means his only function.

The archangel makes things visible, his triumph over his nemesis Lucifer consists in the fact that the latter must appear in his light at the end, just as the contours of everything that happens here below can only be recognised in this light. Thus, the cantata text points us to another track: we recognise ourselves as what we are only in the light of the “dragon conqueror”, the history of humanity can only be understood in the light of the non-historical, sinfulness only under the auspices of the one who knows no contestation. At the same time, however, it is obvious: This figure is not a figure that can be emulated, there can be no imitatio Michaelis. Michael remains a figure that is only imaginable for us by breaking itself against us and against the world, which remains invisible without resistance. She needs the strife that will now arise.

Philipp Theisohn

This text has been translated with DeepL (www.deepl.com).