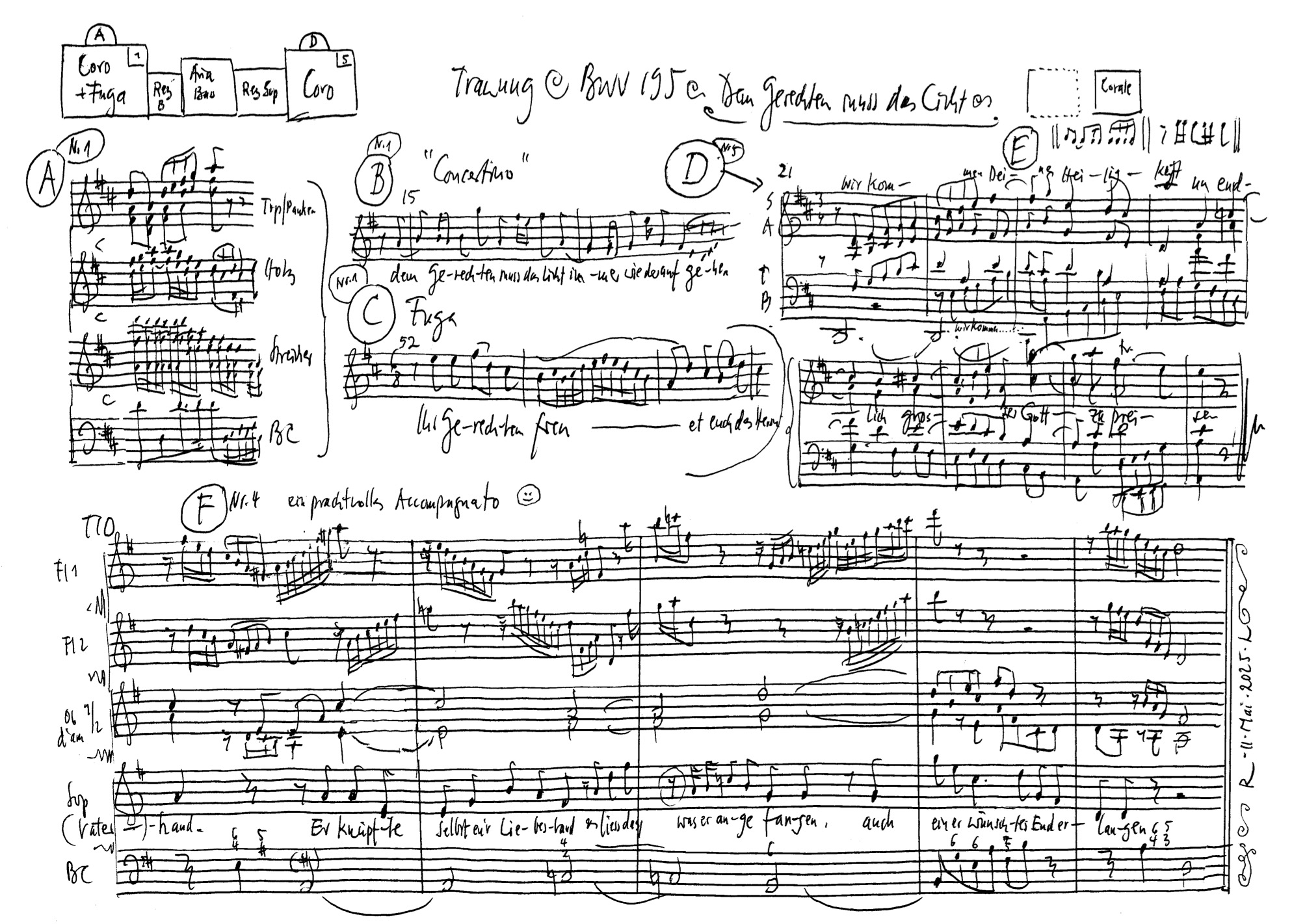

Dem Gerechten muss das Licht

BWV 195 // For a wedding

(For the righteous must the light) for soprano, alto, tenor and bass, vocal ensemble, trumpet I-III, timpani, transverse flute I+II, oboe I+II, strings and basso continuo

Place of composition in the church year

Pericopes for Sunday

Pericopes are the biblical readings for each Sunday and feast day of the liturgical year, for which J. S. Bach composed cantatas. More information on pericopes. Further information on lectionaries.

Choir

Soprano

Lia Andres, Noëmi Tran-Rediger, Alexa Vogel, Mirjam Wernli, Ulla Westvik

Alto

Anne Bierwirth, Antonia Frey, Tobias Knaus, Laura Kull

Tenor

Klemens Mölkner, Florian Glaus, Sören Richter

Bass

Israel Martins, Philippe Rayot, Julian Redlin, Tobias Wicky

Orchestra

Conductor

Rudolf Lutz

Violin

Renate Steinmann, Monika Baer, Patricia Do, Elisabeth Kohler Gomes, Olivia Schenkel, Salome Zimmermann

Viola

Susanna Hefti, Claire Foltzer, Matthias Jäggi

Violoncello

Martin Zeller, Bettina Messerschmidt

Violone

Guisella Massa

Traverse flute

Tomoko Mukoyama, Sara Vicente

Oboe

Katharina Arfken, Clara Espinosa Encinas

Bassoon

Susann Landert

Trumpet

Rudolf Lörinc, Peter Hasel, Klaus Pfeiffer

Timpani

Inez Ellmann

Harpsichord

Thomas Leininger

Organ

Nicola Cumer

Musical director & conductor

Rudolf Lutz

Workshop

Participants

Rudolf Lutz, Pfr. Niklaus Peter

Reflective lecture

Speaker

Nicole Althaus

Recording & editing

Recording date

23/05/2025

Recording location

Trogen (AR) // Evang. Kirche Trogen

Sound engineer

Stefan Ritzenthaler

Producer

Meinrad Keel

Executive producer

Johannes Widmer

Production

GALLUS MEDIA AG, Schweiz

Producer

J.S. Bach-Stiftung, St. Gallen, Schweiz

Librettist

Period of composition

First version around 1728/31; last version around 1748/49;

Leipzig and/or surrounding region (?)

Text

Poet unknown, movement 1: Psalm 97,11-12

Libretto

1. Chor

«Dem Gerechten muß das Licht immer wieder aufgehen

und Freude den frommen Herzen. Ihr Gerechten, freuet

euch des Herrn und danket ihm und preiset seine

Heiligkeit.»

2. Rezitativ – Bass

Dem Freudenlicht gerechter Frommen

muß stets ein neuer Zuwachs kommen,

der Wohl und Glück bei ihnen mehrt.

Auch diesem neuen Paar,

an dem man so Gerechtigkeit

als Tugend ehrt,

ist heut ein Freudenlicht bereit,

das stellet neues Wohlsein dar.

O! ein erwünscht Verbinden!

so können zwei ihr Glück eins an dem andern finden.

3. Arie — Bass

Rühmet Gottes Güt und Treu,

rühmet ihn mit reger Freude,

preiset Gott, Verlobten beide!

Denn eu’r heutiges Verbinden

läßt euch lauter Segen finden,

Licht und Freude werden neu.

4. Rezitativ – Sopran

Wohlan, so knüpfet denn ein Band,

das so viel Wohlsein prophezeihet.

Des Priesters Hand

wird jetzt den Segen

auf euren Ehestand,

auf eure Scheitel legen.

Und wenn des Segens Kraft hinfort an euch gedeihet,

so rühmt des Höchsten Vaterhand.

Er knüpfte selbst eu’r Liebesband

und ließ das, was er angefangen,

auch ein erwünschtes End erlangen.

5. Chor

Wir kommen, deine Heiligkeit,

unendlich großer Gott, zu preisen.

Der Anfang rührt von deinen Händen,

durch Allmacht kannst du es vollenden

und deinen Segen kräftig weisen.

Post Copulationem

[Arie]

Bist du bei mir, geh ich mit Freuden

zum Sterben und zu meiner Ruh.

Ach, wie vergnügt wär so mein Ende,

es drückten deine schönen Hände

mir die getreuen Augen zu!

6. Choral

Nun danket all und bringet Ehr,

ihr Menschen in der Welt,

dem, dessen Lob der Engel Heer

im Himmel stets vermeldt.

This text has been translated with DeepL (www.deepl.com).

Nicole Althaus

Dear admirers of Bach, ladies and gentlemen, good evening

I have listened to a lot of Bach in recent weeks. Not just the wedding cantata, which I have been invited to reflect on today. First, there were the sonatas for violin, the violin concertos that I tried to play when I was young and toyed with the idea of studying at the conservatory. Bach taught me humility. Even for the best virtuosos, daring to tackle his music means confronting their own shortcomings. And I was no virtuoso. Bach forgives nothing, no vibrato to cover up a tiny fingering mistake, no cheating with the bow. He exposes musical vanity and self-promotion like a fact checker exposes journalistic dishonesty.

It is not Bach’s fault that I ultimately chose the keys of the computer over the strings of the violin, writing over playing. But he still determines the code: A good text is one in which every word has to be right, and if there is no genuine new thought, even the most eloquent foreign words and the most beautiful metaphors cannot distract from this.

That is precisely why, ladies and gentlemen, I have worked on this reflection as I once did on the Violin Concerto in A minor or the Violin Sonata No. 3 in C major. My first thought when I heard the wedding cantata was: this is Bach in the form of exquisite chilled champagne, with which one toasts a bride and groom in a well-tended English garden. My second thought when reading the verses followed immediately: Why on earth should I, who have never stood before an altar as a bride, but recently before a divorce judge, publicly reflect on wedding music? What can I, who does not believe in God, tell you about the sacred bond of marriage? What about love, when it only comes to me as half-baked (what an appropriate Helvetism) as Bach’s sonata on the violin?

But then I heard this Bach cantata on endless repeat on my daily walk along the Wehrenbach in Zurich: the long first part, the opening chorus, the recitative in which the couple and their union are sung about, the unusual bass aria, the second recitative, the moment of the wedding ceremony, twenty long minutes of faith, love and hope. And then, very briefly, the two horns sound in the final chorus – Bach’s musical kiss, which makes you think you can hear love. Twenty minutes of singing about happiness and blessings. And not even a whole minute of fulfilment. No eternal radiance, no fairy-tale ending.

Bach’s cantata ignites the light of love and leaves it to life.

And I can tell you a thing or two about that, ladies and gentlemen. After all, people have always pondered love. Especially those who ponder for a living. So I can tell you a thing or two about how it feels when love is kindled. And even more about how difficult it is not to smother the fire of love in everyday life. Because love is not just a feeling, but a skill that must be learned. From A to Z. From beginning to end.

In any case, when I listen to the cantata, it reminds me of the long-awaited beginning, the first kiss. Not so much my own first kiss, but more generally the recurring spectacle of human awakening in spring.

I have been able to witness this spectacle almost daily for the past few weeks in the schoolyard below my balcony: the young lovers come from opposite directions in the evening, when the last children have been called in for dinner and the yard is deserted except for a bicycle lying on the ground. The two teenagers must see each other from afar, but every evening they pretend to meet by chance. He strolls slowly along the gravel path, legs wide apart, seemingly engrossed in a phone conversation with a friend, and every time he laughs a little too loudly, he adjusts his oversized hoodie with a casual movement that he must have practised in front of the mirror.

Every few steps, she tosses her long hair over her shoulder with her left hand and scrolls through her smartphone with her right so that he can see that she’s not looking for him. And when they meet near the bench by the tree trunk under the large plane tree, they nod awkwardly, not knowing where to look, and hug each other, still holding their smartphones in their hands.

They have been coming here every evening since spring began. Perhaps they are not allowed to be seen together where they live. Perhaps he is Muslim and she is Christian, or vice versa. Perhaps they live with many siblings and have no privacy. In any case, every evening they start over as if yesterday never happened. They sit down on the bench, him with his legs spread wide, her making herself small, their eyes fixed on their smartphones, where the world they share exists.

The props and costumes have changed over the years, but the main characters have remained exactly the same. In my day, the Julias wore headbands and carried Walkmans, which contained their shared world. Romeo would arrive at the meeting place on his moped, even if it was only fifty metres away. But like the two teenagers in the courtyard, he played the hero and she played his beloved. And they did so with the heart-rending awkwardness that only adolescents can manage. Nothing but clumsy growth, crude clichés and oversized coolness.

But then the young woman in the courtyard breaks out of her role, stands up resolutely, raises her arms to tie her hair into a ponytail, knowing full well that her short T-shirt now reveals her slim waist. Promptly, the young man puts his mobile phone aside, pulls her by the hips onto his lap and kisses her. It was only a brief kiss. But for a moment, the two of them stepped out of their roles, forgetting that he was supposed to be the hero and she was supposed to be the object of his adoration. They hung on each other’s lips, oblivious to everything else, and it didn’t matter where they came from, what they believed or what everyone else thought.

If the courtyard had been a stage instead of a schoolyard, I would have shouted ‘Bravo!’ and applauded. It was an ancient play, but even after seeing it countless times, it was still as moving as the first morning of spring when the delicate blossoms open.

Great love, ladies and gentlemen, exists only in the singular. No one speaks of great loves. I am convinced that my Romeo and his Juliet also believe in it when they kiss, because human beings still give their hearts to one person, perhaps even anew each time.

We also believe in great love when people around us fail at it. Today just as yesterday. Everything has changed, of course: water comes out of the tap; you no longer have to fetch it from the well. Light comes from the socket, and your lover, well, today they come from the internet. But still we believe that love should work as it always has.

Yet we don’t even know what it has always been like. We learn, read and hear about romantic love, which does not exist in the plural, and forget that love does not exist independently of the here and now. On the contrary: as sociologist Eva Illouz demonstrates in her famous work Why Love Hurts, it is shaped by very specific socio-cultural conditions. When women can earn their own money and men can cook their own meals, when sex is available without a ring and old age can be enjoyed without children, centuries-old contracts between the sexes are dissolved or redefined.

When this cantata was written, marriage was usually arranged; it was a business transaction, a barter, based on many rules and norms, and in the best case led to love and perhaps even desire. Today, it is exactly the opposite. Modern relationships are based first and foremost on desire and perhaps love, and at best lead to rules – self-imposed norms, of course.

Even in a church wedding, the marriage vows are no longer a one-size-fits-all formula as they were in Bach’s day. At the beginning, the couple discusses what the priest should say and what not, and often the bride and groom formulate their vows to each other themselves.

Female subordination and obedience? Forget it.

‘Till death do us part?’

The statistics tell a different story.

– Faithfulness? In the age of situational relationships and polyamory, it has become a science.

What remains is love and honour. The latter is perhaps the core of a relationship. It always has been. And I don’t mean honour in the sense of worship and subordination, of curtsies and bows. I mean the appreciation that turns honour into equality. As long as you desire your partner, this appreciation is easy. The word ‘desire’ echoes the word ‘honour’. But when the music has faded, when the white dress is hanging in the wardrobe, the children are crying, the milk is boiling over, money is tight and work is stressful, then appreciation becomes more difficult. Bach had twenty children from two marriages, and even if he probably didn’t change nappies, he certainly knew why ‘those who want to do right by others must always see the light’.

This is how the text of the cantata puts it, and this brings us back to the music that, after the wedding kiss, returns us to everyday life. ‘Now give thanks and honour, all you people in the world’ – so goes the verse in the final chorus. The cantata ends with a call for gratitude and appreciation, which must be demonstrated again and again after the exchange of rings, after the wedding night and the honeymoon. If love is to succeed. And I would like to add here that both are also required when love does not succeed. Then perhaps even more so. A marriage can be divorced, but the bond between two people remains, not only if they have children. And if the couple has ‘seen the light again and again,’ the appreciation remains.

Ladies and gentlemen, as I said at the beginning, my marriage failed, I have been separated for a long time and recently divorced.

But perhaps I have learned more about love in the years of separation than in the many years of marriage. For example, I can no longer agree with Leo Tolstoy: ‘All happy families are alike; every unhappy family is unhappy in its own way.’

With these words, the great Russian author opens his novel of the century, Anna Karenina. I agree with him about family unhappiness, which is as varied as the people who cause it. But I disagree with him about happiness.

Happy families are not all the same either. Imagine, for example, this one: the parents, no longer young and not yet old, are sitting on the beach with a glass of wine. Their first kiss was ages ago, their last one a while back, and their children are no longer children, but now they run hand in hand in shoes and clothes into the waves that rise green before them and then break into white spray. The parents hear the laughter and let it infect them. The sky is a clear blue and what they are looking at needs no words: their children, two wonderful young women, are the result of their love, bursting with a zest for life and exuberance.

This love still exists, even though the marriage has broken down.

These days together by the sea are not fictional, even if they are the exception today. Not because of the parents, who are no longer a couple. But because of the daughters, who are no longer children and have their own plans. Nevertheless, there have been many similar moments in the fifteen years since the separation: birthdays, Christmas celebrations, Easter brunches, but also hikes or spontaneous movie nights during the week. Mother and father talked about the children’s problems and successes, about their own jobs, about God and the world. There were no arguments about laundry, shopping, cleaning or other trivial matters. Because there is no longer a shared home or laundry. The little things have disappeared, but the big picture remains.

It wasn’t always like that. When people separate, there is pain, fear and anger at first. Because love leaves its mark even when the person you once loved with all your heart is now holding someone else’s hand. But first comes grief. When you separate – something most people in this church have probably experienced at some point in their lives – you don’t just separate from the other person. You also say goodbye to a version of yourself. The version that believed, hoped and wished that true love existed, and in the singular.

So breaking up is difficult. Untangling yourself internally is the real art. It can only succeed if honour remains even though desire has disappeared. If, as the cantata says, you ‘honour justice as a virtue’, if you untie the knot with mutual appreciation, then what you call family will not break apart. Then it can even become happy and prove Tolstoy’s dictum false.

That’s why it’s worth it, but I don’t need to tell you that, ladies and gentlemen. From A to Z. Not only is falling in love worth it, but loving is too. It’s even worth it in the plural.

Because love is never in vain. It shapes us, shakes us up, makes us soft and alert. And if we are lucky and grow through it, then it stays with us. Perhaps that is its greatest gift: that it takes many forms, that you can leave without losing everything. And that sometimes it is only when you let go that you realise that the honour and loyalty you once promised in a church or at the registry office can actually last beyond separation, ‘until death do you part’.

It is then honour and loyalty that go beyond the act of promising to marry. It is honour for the history you have written together. And loyalty to the children who were never part of a contract or deal, but the fruit of genuine feelings. It is appreciation for shared memories and the commitment you feel towards each other.

What remains, then, is appreciation, honouring each other as equals. The light that shines again and again when you cultivate a fair, i.e. clear and loving, relationship with the other person, with your counterpart.

Thank you.