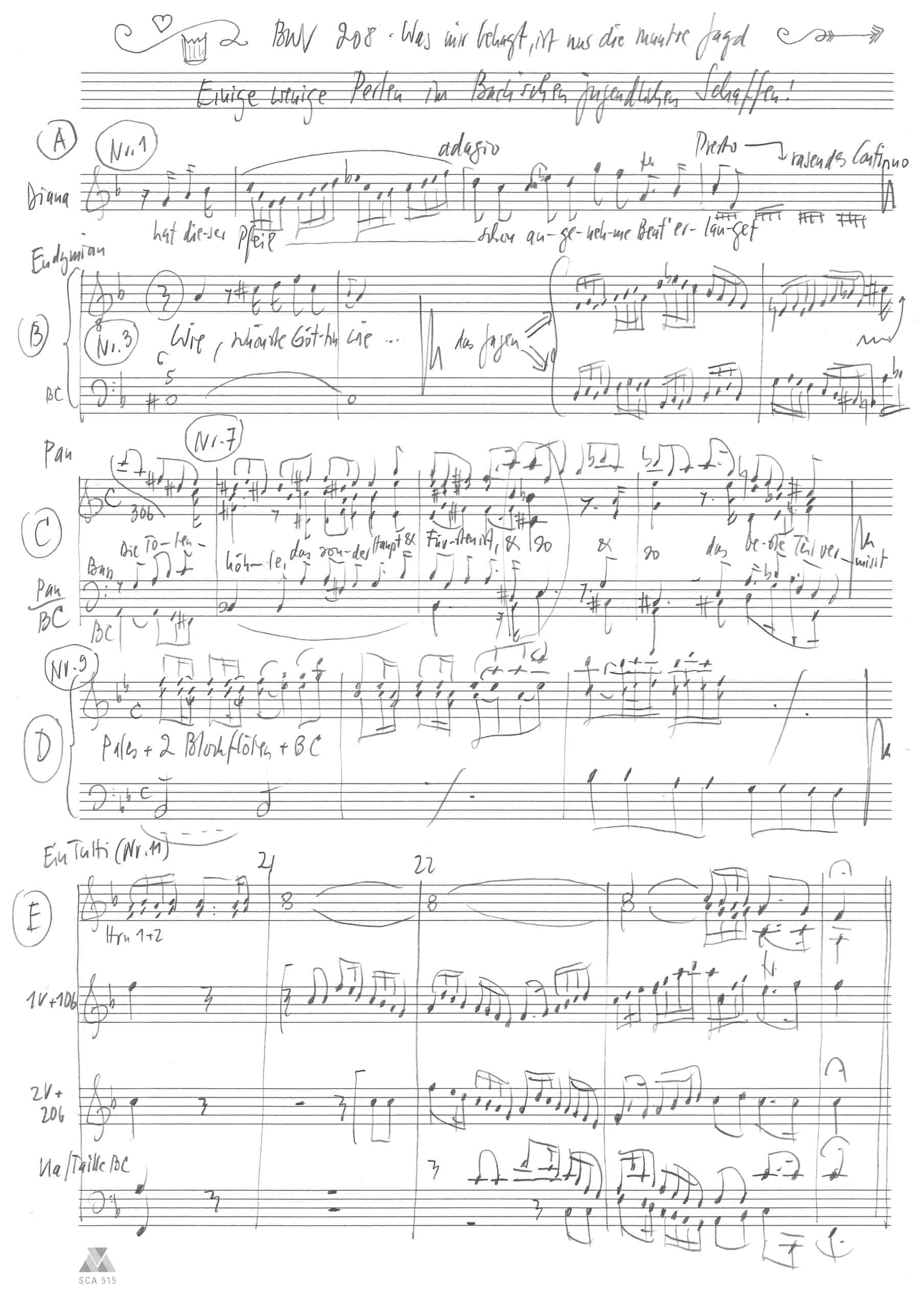

Was mir behagt, ist nur die muntre Jagd

BWV 208 // Secular occasional music

(What pleases me is above all the lively hunt) for soprano I+II, tenor and bass, horn I+II, oboe I+II, lute, taille, recorder I+II, strings and basso continuo

Would you like to enjoy our videos ad-free? Subscribe to YouTube Premium now...

Workshop

Reflective lecture

Bonus material

Orchestra

Conductor and Harpsichord

Rudolf Lutz

Violin

Renate Steinmann, Concertmaster, Monika Baer

Viola

Susanna Hefti

Violoncello

Martin Zeller, Daniel Rosin

Violone

Markus Bernhard

Horn

Olivier Picon, Thomas Müller

Recorder

Annina Stahlberger, Teresa Hackel

Oboe

Andreas Helm, Kerstin Kramp, Katharina Arfken

Taille

Katharina Arfken

Bassoon

Susann Landert

Lute

Julian Behr

Musical director & conductor

Rudolf Lutz

Workshop

Participants

Rudolf Lutz, Karl Schmuki

Reflective lecture

Speaker

Leonhard Horowski

Recording & editing

Recording date

25/10/2019

Recording location

Gossau (SG) // Fürstenlandsaal

Sound engineer

Stefan Ritzenthaler, Nikolaus Matthes

Producer

Meinrad Keel

Production manager

Johannes Widmer

Production

GALLUS MEDIA AG, Schweiz

Producer

J.S. Bach-Stiftung, St. Gallen (Schweiz)

Librettist

First performance

21/22 February 1713, Weissenfels

For the birthday of Herzog Christian von Sachsen-Weissenfels

Text

Salomo Franck

In-depth analysis

Cantata BWV 208 was most likely first performed in 1713 for the 31st birthday of Duke Christian of Saxe-Weissenfels at the hunting residence that still stands on the eastern periphery of the town. Weissenfels was the seat of a line of the Electorate of Saxony, and in the mid-17th century, it had grown into a well-known Residenz for music under the aegis of Heinrich Schütz, who spent his later years there. The town is connected not only with famous names such as Johann Philipp Krieger and Johann Beer, but also with the discovery of the young George Frideric Handel. And last but not least, Weissenfels was also home to court deacon Erdmann Neumeister, the great moderniser of Protestant church texts, whose interest in the theatrical genres of recitative and aria was no doubt inspired by the vicinity of the court opera and church to the castle Schloss Neu-Augustusburg.

Why Bach and librettist Salomo Franck, two young outsiders from Weimar, were selected to write the work instead of the wellestablished Kapellmeister Johann Krieger remains a matter of conjecture. Whatever the exact circumstances, however, the opportunity enabled Bach both to discover the genre of courtly festive cantatas and to try out a collaboration with Franck, who, from 1714, provided the texts for many of Bach’s exquisite Weimar cantatas. The fact that Bach in his later career still regarded his Hunt Cantata as a worthy opus is proved by its revivals in Weimar, Leipzig and Weissenfels; the performance parts, however, were unfortunately lost in this process.

Franck’s libretto, for its part, seems to imply a double layer of meaning, particularly in the opening movements. The praise of the godly hunt, for instance, morphs into such a demonstrative defence that a criticism of this wasteful pastime shines through. In a contrasting movement, the heavily accented “Liebesnetze” (nets of love) give voice to the need for a son and heir to the line. Indeed, Christian’s brother and predecessor had already died without male issue – a fate that would also befall Christian – and after the death of the last brother, Johann Adolf II in 1746, the Saxe-Weissenfels line reverted to the main house in Dresden. As a whole, the text gives the impression of holding aristocratic rule to account in a fundamental sense by expressing the expectation that the “good shepherd” should rule prudently and economically. That the duchy’s extravagant hunting craze was not scaled back in favour of prudent land conservation, however, was made abundantly clear at latest by its financial collapse in 1719; Bach’s ongoing popularity, by contrast, saw him named Kapellmeister in 1729.

Our recording opens with the instrumental setting BWV 1040, which is noted at the end of the score and is motivically related to aria number 13. In a later reworking, the setting was added as a ritornello to “Mein gläubiges Herz” (My heart ever faithful), a parody aria on the same material from the Pentecost cantata BWV 68 (Leipzig 1725). This, however, does not exclude its use as an opening sinfonia for at least one of the Weissenfels performances. Indeed, used as an introduction, the setting lends light-footed momentum to the opening recitative with its delightful articulation of a shooting arrow; here it is probably less the goddess Diana than the duke himself who, over the racing continuo passages, declares his passion for the hunt. The following aria i s t hus d ominated b y r ousing h orn fi gures, and while the breathless song of Diana’s chase verges on caricature, her energetic gestures nonetheless seem to silence all the “Spötter” (scorners).

In the next recitative, we are introduced to Endymion, who in his role as the spurned lover fulfils a courtly topos while also delivering an onomatopoeic criticism of “Jägerei” (hunting). His ensuing aria opens with an expressive continuo line in the plaintive key of D minor; while “Amors Netze” (cupid’s nets) are set as a series of interrupted cadences, the tight “Bande” (bonds) of the middle section seems to emphasise the troublesome business of courting and loving. Christian, perhaps in view of his considerably older wife, may have been in need of a little encouragement.

The following duet for Diana and Endymion then proffers a compromise that elegantly reveals the reason for the festivities – although Diana’s love for Endymion is steadfast, it must be withheld this one day while she attends to a more luminous figure: birthday boy Christian. Reconciled to this devotion to the state, Endymion joins in the “Freuden-Opfer” (joyous offering) set in the brilliant key of C major.

In the next pair of recitative and aria movements, Pan joins the scene with his sonorous bass voice. While the timbre of three oboes evokes the pastoral sound of shepherds’ pipes, the dotted phrases are regal and overturelike. When Pan lays down his shepherd’s crook before Christian’s ruling sceptre, the small duchy is transformed into a true Arcadia that can come to life only through the deeds of its prince. The antithesis – a leaderless “Totenhöhle” (deadman’s hollow) – is then described in drastic tones by Franck and closely interpreted by Bach in rapid modulations; perhaps this bleak passage – unusual in festive music – is connected to the death of the prince’s brother Johann Georg less than one year earlier, an event that helps explain why the new prince in May 1712, just a few weeks thereafter, married Luise Christiana von Stolberg-Ortenberg.

Recitative number eight brings the entry of the last well-wisher, Pales, thus completing the four-part vocal ensemble. Her aria “Schafe können sicher weiden” (Sheep may safely graze) is not only ample proof that this lesserknown deity, too, firmly belongs to the pastoral world; it is also one of Bach’s best-loved compositions that is heard in an endless variety of arrangements to this day. In this setting, the gently repeated notes of the continuo, the blissful-serene recorder figures and the softly ringing cantilena meld to realise an idyll reminiscent of Handel’s Roman cantatas; here, the happy fellowship and muted gestures seem to evoke the contentment and modesty that the people of Weissenfels and Sangerhausen no doubt desired from the new ducal couple.

The soprano recitative number ten acts as a transition to the festive chorus “Lebe Sonne dieser Erden” (Live, O sun of this our earth now), a setting that employs the full ensemble for the first time. The series of short fugal entries showcases Bach’s contrapuntal skill ere the movement develops into an efficient concerto grosso scored with horns. With the homophonic writing for all voices in the middle section, Bach treated his listeners to a familiar courtly serenade; whereas such music in a church cantata would generally introduce the sermon, here it no doubt heralded the arrival of food platters.

The following movements progress with no need for recitatives or actual plot development. As such, they form a suite of arias that function akin to the end-of-scene dances in many a baroque opera and allow the protagonists to present a light-hearted encore. Diana and Endymion, accompanied by a distinctive violin obbligato, open with a duet whose enchanting simplicity transforms the comforting notion of a country freed of all sadness (“vom Leide befreit”) into a tangible vision. Aria number 13, with a serene cantilena, takes up the topos of the content lowly flock; whether, in the industrious continuo, the listener detects the toil of rural subjects in supporting their nobles is a matter of interpretation. Pan, the unofficial chief steward, then takes to the stage with a romping dance aria in breathless 3⁄8-figures; the eight declamations of “Es lebe der Herzog” (Long life to Prince Christian!) towards the end of the movement no doubt had the effect of a toast, in which the birthday revellers – most certainly tipsy – were ready to join in.

With the closing chorus “Ihr lieblichste Blicke” (Ye loveliest glances), Bach displays the full breadth of his skill in an expansive fourpart setting replete with enchanting combinations. The way in which the composer unites compositional order and sensitivity to text (for example, on the word “ewig” – eternity) paves the way for sacred works such as “Christen, ätzet diesen Tag” (Christians, etch ye now this day) BWV 63 and foreshadows his great homage cantatas of the 1730s. Scored with resounding horns, this da-capo movement includes an elegant, four-part aria setting that would have echoed in the minds of the delighted audience for some time.

Libretto

1. Rezitativ — Sopran

Diana

Was mir behagt,

ist nur die muntre Jagd!

Eh noch Aurora pranget,

eh sie sich an den Himmel wagt,

hat dieser Pfeil schon angenehme Beut erlanget.

2. Arie — Sopran

Diana

Jagen ist die Lust der Götter,

jagen steht den Helden an.

Weichet, meiner Nymphen Spötter,

weichet von Dianen Bahn!

3. Rezitativ — Tenor

Endymion

Wie, schönste Göttin, wie?

Kennst du nicht mehr dein vormals halbes Leben?

Hast du nicht dem Endymion

in seiner sanften Ruh

so manchen Zuckerkuss gegeben?

Bist du denn, Schönste, nu

von Liebesbanden frei?

Und folgest nur der Jägerei?

4. Arie — Tenor

Endymion

Willst du dich nicht mehr ergötzen

an den Netzen,

die dir Amor legt?

Wo man auch, wenn man gefangen,

nach Verlangen

Lust und Lieb in Banden pflegt.

5. Rezitativ — Sopran, Tenor

Diana

Ich liebe dich zwar noch!

Jedoch

ist heut ein hohes Licht erschienen,

das ich vor allem muss

mit meinem Liebeskuss

empfangen und bedienen.

Der teure Christian,

der Wälder Pan,

kann in erwünschtem Wohlergehen

sein hohes Ursprungsfest itzt sehen.

Endymion

So gönne mir,

Diana, dass ich mich mit dir

itzund verbinde,

und an «ein Freuden-Opfer» zünde.

Diana, Endymion

Ja! Ja! Wir tragen unsre Flammen

mit Wunsch und Freuden itzt zusammen!

6. Rezitativ — Bass

Pan

Ich, der ich sonst ein Gott

in diesen Feldern bin,

ich lege meinen Schäferstab

vor Christians Regierungs-Szepter hin!

Weil der durchlauchte Pan das Land so glücklich machet,

dass Wald und Feld und alles lebt und lachet!

7. Arie — Bass

Pan

Ein Fürst ist seines Landes Pan,

gleich wie der Körper ohne Seele

nicht leben, noch sich regen kann,

so ist das Land die Totenhöhle,

das sonder Haupt und Fürsten ist

und so das beste Teil vermisst.

8. Rezitativ — Sopran

Pales

Soll denn der Pales Opfer hier das letzte sein?

Nein! Nein!

Ich will die Pflicht auch niederlegen,

und da das ganze Land von Vivat schallt,

auch dieses schöne Feld

zu Ehren unsrem Sachsenheld

zur Freud und Lust bewegen!

9. Arie — Sopran

Pales

Schafe können sicher weiden,

wo ein guter Hirte wacht.

Wo Regenten wohl regieren,

kann man Ruh und Friede spüren

und was Länder glücklich macht.

10. Rezitativ — Sopran

Diana

So stimmt mit ein

und lasst des Tages Lust vollkommen sein!

11. Arie — Chor

Lebe, Sonne dieser Erden,

weil Diana bei der Nacht

an der Burg des Himmels wacht,

weil die Wälder grünen werden,

lebe, Sonne dieser Erden!

12. Arie — Sopran , Tenor

Diana, Endymion

Entzücket uns beide,

ihr Strahlen der Freude,

und zieret den Himmel mit

Demantgeschmeide,

Fürst Christian weide

auf lieblichsten Rosen, befreiet vom Leide!

13. Arie — Sopran

Pales

Weil die wollenreichen Herden

durch dies weitgepriesne Feld

lustig ausgetrieben werden,

lebe dieser Sachsenheld!

14. Arie — Bass

Pan

Ihr Felder und Auen,

lasst grünend euch schauen,

ruft Vivat itzt zu!

Es lebe der Herzog in Segen und Ruh!

15. Chor

Ihr lieblichste Blicke,

ihr freudige Stunden,

euch bleibe das Glücke

auf ewig verbunden!

Euch kröne der Himmel mit süßester Lust!

Fürst Christian lebe! Ihm bleibe bewußt,

was Herzen vergnüget,

was Trauern besieget!