Du wahrer Gott und Davids Sohn

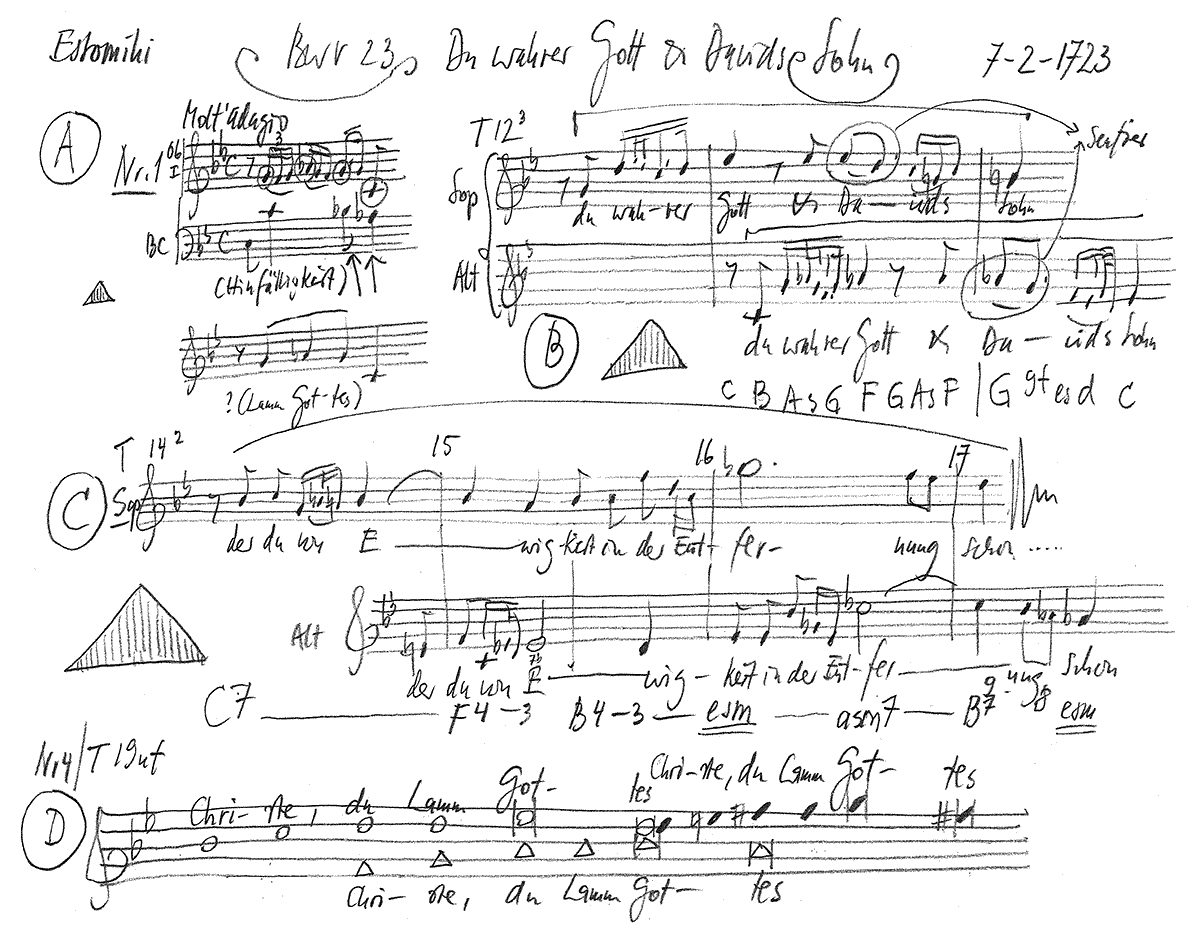

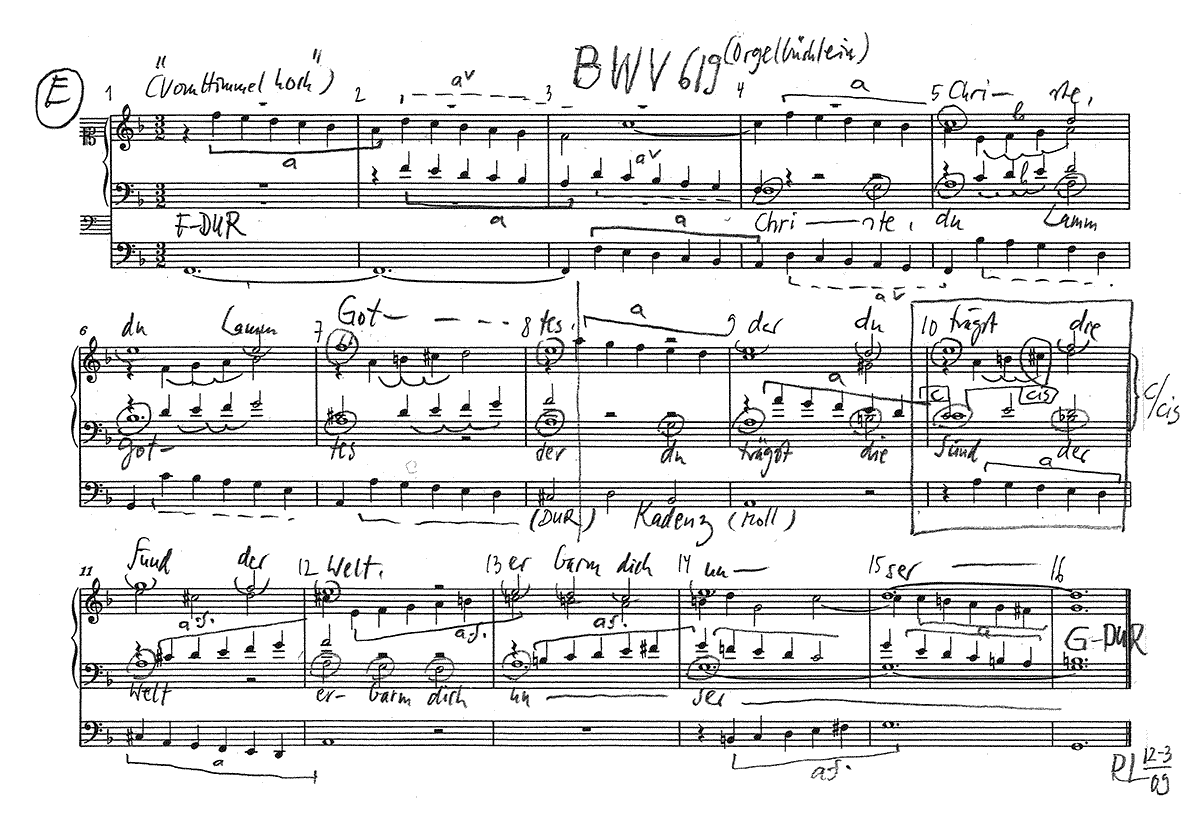

BWV 023 // For Estomihi

(Thou, very God and David’s son) Version in C minor for soprano, alto, tenor and bass, vocal ensemble, oboe I+II, bassoon, strings and continuo.

Would you like to enjoy our videos ad-free? Subscribe to YouTube Premium now...

Workshop

Reflective lecture

Choir

Soprano

Susanne Frei, Leonie Gloor, Guro Hjemli, Noëmi Tran Rediger

Alto

Jan Börner, Antonia Frey, Olivia Heiniger, Lea Scherer

Tenor

Marcel Fässler, Clemens Flämig, Manuel Gerber

Bass

Matthias Ebner, Fabrice Hayoz, Philippe Rayot

Orchestra

Conductor

Rudolf Lutz

Violin

Renate Steinmann, Martin Korrodi, Ildiko Sajgo, Olivia Schenkel, Marjolein Streefkerk, Livia Wiersich

Viola

Susanna Hefti, Martina Bischof

Violoncello

Maya Amrein

Violone

Iris Finkbeiner

Oboe

Kerstin Kramp, Andreas Helm

Bassoon

Susann Landert

Organ

Norbert Zeilberger

Musical director & conductor

Rudolf Lutz

Workshop

Participants

Karl Graf, Rudolf Lutz

Reflective lecture

Speaker

Konrad Hummler

Recording & editing

Recording date

03/13/2009

Recording location

Trogen

Sound engineer

Stefan Ritzenthaler

Director

Meinrad Keel

Production manager

Johannes Widmer

Production

GALLUS MEDIA AG, Switzerland

Producer

J.S. Bach Foundation of St. Gallen, Switzerland

Librettist

Text No. 1–3

Poet unknown

Text No. 4

Agnus Dei, German translation by Martin Luther

First performance

Estomihi,

7 February 1723

Libretto

1. Arie (Duett)

Du wahrer Gott und Davids Sohn,

der du von Ewigkeit, in der Entfernung schon,

mein Herzeleid und meine Leibespein

umständlich angesehn, erbarm dich mein.

Und lass durch deine Wunderhand,

die so viel Böses abgewandt,

mir gleichfalls Hülf und Trost geschehen!

2. Rezitativ (Tenor)

Ach! gehe nicht vorüber,

du aller Menschen Heil

bist ja erschienen,

die Kranken und nicht die Gesunden zu bedienen.

Drum nehm ich ebenfalls an deiner Allmacht teil;

ich sehe dich auf diesen Wegen,

worauf man

mich hat wollen legen,

auch in der Blindheit an.

Ich fasse mich

und lasse dich

nicht ohne deinen Segen.

3. Chor (mit Tenor und Bass)

Aller Augen warten, Herr,

du allmächtger Gott, auf dich,

solo

und die meinen sonderlich,

tutti

aller Augen warten, Herr,

du allmächtger Gott, auf dich,

solo

Gib denselben Kraft und Licht,

laß sie nicht

immerdar in Fünsternüssen.

tutti

Aller Augen warten, Herr,

du allmächtger Gott, auf dich.

solo

Künftig soll dein Wink allein

der geliebte Mittelpunkt

aller ihrer Werke sein.

tutti

Aller Augen warten, Herr,

du allmächtger Gott, auf dich,

solo

bis du sie einst durch den Tod

wiederum gedenkst zu schliessen.

tutti

Aller Augen warten, Herr,

du allmächtger Gott, auf dich,

4. Choral

Christe, du Lamm Gottes,

der du trägst die Sünd der Welt,

erbarm dich unser!

Christe, du Lamm Gottes,

der du trägst die Sünd der Welt,

erbarm dich unser!

Christe, du Lamm Gottes,

der du trägst die Sünd der Welt,

gib uns dein’ Frieden! Amen.

Konrad Hummler

“God’s death is the birth of the free, self-responsible human being”.

What institutionalised Christianity has made us miss for 2000 years.

There was a children’s Bible in my parents’ house, large-format, heavy, with golden letters and a glossy black laminated linen cover, illustrated with pictures that compensated for their lack of colour – they must have been steel engravings or etched drawings – with drama and tangible physicality. From this book, which was both attractive and frightening, the older sister had to read to the younger brother when the parents were not at home in the evening, which was not infrequently the case because of my father’s political activities. My favourite reading concerned Matthew chapter 1, verses 2-16: “Abraham begat Isaac, Isaac begat Jacob, Jacob begat Judas and his brothers, Judas begat Perez and Zerah with Tamar (…)” and so on.

At that time I did not know what this repeatedly used word “beget” meant, but I found it somehow exciting, especially since my sister did not want to explain it to me even after my insistent questions and no corresponding illustration could be found even after extensive research. With the combinatorial talent that is available to every little boy in these matters, I soon realised that this was about descent, about paternity, about origin, and I also realised that this attempt to prove the unbroken family succession came to a standstill precisely at the decisive point, namely with Joseph in verse 16, even more: in obvious contradiction to the Christmas story with the miraculous visit of an angel to the Virgin Mary.

This laid the foundation stone for an understanding of religion that does not derive its certainties from disputable or contradictory quasi-facts. I can do nothing with a God whose existence and nature depend on the path that sperm may or may not have taken from the procreation apparatuses of desert sons into the wombs of their more or less legal wives. “David’s son” leaves me cold, or perhaps even more accurately: stirs up resistance in me, because behind it is an entirely ethnic and patriarchally based understanding of God, as it actually oppresses us when we read the entire Old Testament. An understanding of God that does not include, but rather systematically excludes. What am I to make of a God who rejects Cain, who puts Esau at a disadvantage, who sends Ishmael into the desert, who lets the Canaanites and the Hittites and the Amorites and the Perizzites and the Khivites and the Jebusites be deprived of their ancestral lands, who lets the Philistines prevail or lose, depending on the gusto of the Israelites for “their” God, who is asked even in the most moving texts like Psalm 139: “Should I not hate, O Lord, those who hate you, / Should I not be disgusted with those who rebel against you? / I hate them with fierce hatred, / They have become enemies to me too.”

Anyone who, in addition to all the admittedly always delightful Sunday school stories about Sarah, Rebekah, Jonah and Samuel, takes a look at all the rest of the Old Testament is grateful that this first part of the Bible did not remain, and glad that the matter of the descent of David’s son remained so unclear. Nevertheless, it is not a story of salvation that is presented to us in the Old Testament, but a sequence of endless hardship and suffering. The almost incessant bloodbath is explained monocausally with the repeated turning away of the people of Israel from their only God, whose love for his people consists in binding them to himself again through manifest punishments. At the very beginning of the tragedy, apart from a very small remnant to save the species, he has it miserably drowned, and with it all innocent living beings who had not found a place in the ark of divine action pro specierara.

The danger of the almighty God

If we say to ourselves with relief that this is not and cannot be our religiosity, then at the same time we must also consider that hardly any religion has progressed beyond precisely this image of God: the human being who is supposed to please “his” God through his works, his actions, deeds and omissions. The God who in his “omnipotence” – the term “omnipotence” occurs twice and emphatically in the cantata text – interferes in such a way in the history of man, indeed allows himself to be interfered with. Both the idea that a people, by virtue of its mythically founded past, is allowed to displace another people through aggressive settlements, and the delusion that God’s will is realised in the ultimate form of intensification in the detonation of dynamite belts placed around one’s own body, originate in the idea of God’s taking sides for certain human objectives. Christianity, which has been enriched by the New Testament, must also be included in this fundamental critique of Zionism and Islamism. Almost since the beginning of its existence, it has contributed to the bloody course of world history in an incalculably diverse sequence of wars, persecutions, tortures and burnings. Always, of course, in the name of God Almighty, whose merciful assistance was mostly claimed by all warring parties at the same time. In essence, practical Christianity took up the blood trail of the Old Testament and widened it into a road of hardship and torment through world history and around the globe. What, according to the instructions of the Sermon on the Mount, should have brought love of friends and enemies into the raw world, did not even know how to create at least a balance between caritas and violentia.

The omnipotence of God, what a problematic idea! Not only in the aforementioned sense that this super-hyperpower becomes active through the actions and omissions of human beings, but also and above all in the sense that the course of the world should ultimately depend on it, indeed correspond to the will of the Almighty. Then it would have been the will of God that Hitler came to power, that none of the assassination attempts on him succeeded, that at his behest millions of Jews, including innocent children, were treated like vermin and destroyed. Then it would have been in accordance with a divine plan that Stalin, unhindered by his Allied friends, could have continued Hitler’s work of extermination in his own country. Mao Zedong, as the instrument of the Most High, would have driven seven million of his Chinese comrades to their deaths on the occasion of the Cultural Revolution. The same could be said of Pol Pot in Cambodia. An omnipotent God who does not intervene in the face of such blatant, senseless acts of violence – do we really want to recognise him as the highest authority?

The fiction of divine intervention in world history and in the microcosm of daily coexistence and in the smallest area of our own lives – to which the prayers of repulsion apply – is indeed very problematic. In the final analysis, it relieves the human being of any co-responsibility or primary responsibility, ultimately excuses any major or minor mess and is therefore immoral in every respect.

“All eyes are waiting for you.” So who should we wait for? Certainly not for the partial, angry, loving God of a particular desert people, nor for the descendant from David’s bosom. Not for the almighty ruler of the world who, in view of all the evil suffered and still to be suffered, would have to be a very bloodthirsty God. But for whom then do we wait? Doubting and despairing, we would either have to give up nihilistically or build up a radically different expectation and hope.

Gospel as emancipation

We are to become seeing, is the quintessence of the parable according to Luke 18. Perhaps we should simply look a little better and try to understand. Namely, what the New Testament is essentially about: the death of Jesus, this shameful and helpless end of the Son of God and the blatant non-intervention of the almighty ruler of the world. With the execution of Jesus and the fact that “thunder and lightning disappeared into the clouds”, not only a miracle healer and outstanding itinerant preacher dies, but with him God dies as the intervening and almighty ruler of the world, the idea of a partial and supposedly all-controlling God dies. Judas realises his responsibility and hangs himself. He was the first to understand the revolutionary significance of the Gospel. Of David’s son and of the true God, nothing remains but a corpse, mourned by a few steadfast women.

So God would be dead. Yes, he is dead, that intervening God who rewards and punishes man; he is dead, the God for whom wars are to be waged and suicide bombings carried out; he is dead, the God in whose name men and nations may subjugate others. Cursed be he who thus appears in the name of the Lord! This is the Gospel: the great liberation of man from the yoke of the almighty intervener, the liberation of man from fellow men who arrogate to themselves divine calling: Gospel is emancipation – with all its consequences. Where no world thinker intervenes, chance is allowed to rule. Where providence has no meaning, luck and misfortune may strike the “right” or the “wrong”. And man may, indeed must, assert himself in this earthly existence characterised by sheer uncertainty with all the possibilities and instruments at his disposal. His doing or not doing is highly relevant. Man is responsible in every respect.

But what then remains of the Almighty? what are all eyes to wait for? Is there anything left at all? I mean: yes! what remains is precisely everything that eludes the tangible, the factual. we call it faith. The mustard seed, then, to which God deliberately reduces himself through the death of the cross. The barely visible, perceptible power, which under certain circumstances, however, grows to astonishing growth and potent blossoming. Faith stands beyond control, rules, intervention, correction; faith stands above history, which is, after all, only a stringing together of facts that have come about by chance, of facts that have been negligently allowed or deliberately willed.

History is above all about power. Man can exercise power. Power, in its ultimate form, means killing. Man can kill and does so regularly. Faith, on the other hand, is about overcoming death, and it is in this that we might call “omnipotent”: beyond all human power, in the incomprehensibly great and eternal. The Gospel promises us that this incomprehensibly great and eternal is a gracious, merciful authority that judges everything, that is, puts right what we could not or would not do properly.

If faith and fact are mutually exclusive, then we are not left alone in our responsibility for a world that must function without the direct action and intervention of a higher authority in our often rather shabby, laborious, sad walk through our life on this earth without a transcendental presence. Provided we believe it, or we are equipped with the necessary transcendental antennas, we have inklings and signs at our disposal. Amplitude and frequencies may be quite individual and the readiness to receive may also depend on mood, but all in all, God’s presence is in any case of a very personal nature.

Intuitions of the divine

Three premonitions come to mind that make me ready to understand what it could mean when “we are judged, that is, when we put right what we ourselves could not or would not do properly”.

The first inkling occurs when, after the climax of the exertion of a mountain tour, I look out over peaks and valleys into the vast depths in the warm sunlight of the early afternoon and feel a concordance of body, spirit, nature and sky that can never, ever be of merely material origin. That is the moment when one would like to exult, if one could, and this exultation would be the most honest, because wordless, prayer of thanks to the Creator, who lays such an excess of beauty and aesthetic harmony at one’s feet.

The second foreboding occurs when I suddenly and completely undeservedly experience what is so incomparably aptly described in the so-called Song of Songs, i.e. in Paul’s 1st Letter to the Corinthians, chapter 13, verses 4-7: Long-suffering where I would have deserved impatience, forgiveness where I should have expected revenge or punishment, generosity where actually bean-counting would have been programmed – or better still, when I find myself driven to such non-calculating action against all superficial rationality. For me, accommodating or practised love is an experience that regularly transcends human dimensions, the grace of a presentiment of an even more comprehensive, ultimate mercy.

Yes, and the third inkling comes to me naturally with the music. Namely, when the tense agreement between composition and performers leads to that electrifying mood in which one believes that a spark would be enough for the concert hall – or the church – to vibrate, tremble, explode. Then, when the audience breathes in the same rhythm as the musicians, when they want to sing along, play along, dance along, then, when the so-called groove creates a musical metasphere that no one in the world can explain, that you can only experience.

The signs? They were given to us through the Gospel. The water of baptism and the bread and wine of the Lord’s Supper. No serpent on pillars, no burning bushes, no staring and dead prophet eyes, no many-armed shuddering figures. No national flags with hooks and other crosses on them, nor any with stars of any colour, no ideological writings and tracts, no constellations of celestial bodies, no dawn and no rising or setting sun. Nothing of the sort, just water, bread and wine, in other words, what we need every day when we wash, when we eat and when we want to drink decently. The reduction of the signs to the lowest conceivable level of everyday commodities is a reflection of the reduction of the divine to the mustard seed of faith. Faith would then be, so to speak, an always available “staple food”, available without special spiritual exercises and without special authorisation and patents, without the keys of Peter and without proof of a particularly virtuous way of life. whereby the plea for the “daily bread” in a humanly responsible world would again gain a meaning.

This kind of gospel could have become a universal religion above all other religions, since it is a generalisation of the subject that does not need to fight the other religions, but makes them special cases of a much more general conception of God – just as Einstein’s theory of relativity did not have to declare Newton’s doctrine of gravity to be false, but merely relegated it to the place of a special case. All essential spiritual progress of mankind is not based on the falsification of what has gone before, but establishes a new, more generally valid principle in which the old ideas become special cases.

Christianity would have had the chance to make of the Gospel a relativity of the religious. The reduction of the divine to the unprovable, to the merely believable, to the tiny mustard seed, the elevation of the divine beyond human world history into the realm of the truly almighty, the resurrection and the ultimate mercy, namely, the emancipation of man to responsibility for everything he does or fails to do – that would have been a real revolution. It turned out differently, we know. Christianity quickly institutionalised itself and thus betrayed the Gospel to power and death. Worse, it gave pseudo-legitimacy to institutions and their agents by allowing them to invoke “the Almighty” in one way or another. This presumption is in no way better than that of the suicide bomber who kills innocent people. It is the same presumption that man is allowed to dispose of the “Almighty”. Properly understood omnipotence and resurrection are a long way off, and so we must continue to ask the Lamb of God for mercy.

It is in our hands to put an end to 2000 years of misguided human history. We would have it in our hands to make the display of power and killing in the name of a higher authority a baseless notion. We would have it in our hands to accept a gospel that would be compatible with enlightenment, evolutionary theory and the latest neurological findings. Then, yes, then we would finally bring the Agnus Dei closer to what we all so urgently need: Dona nobis pacem.

This text has been translated with DeepL (www.deepl.com).