Ach wie flüchtig, ach wie nichtig

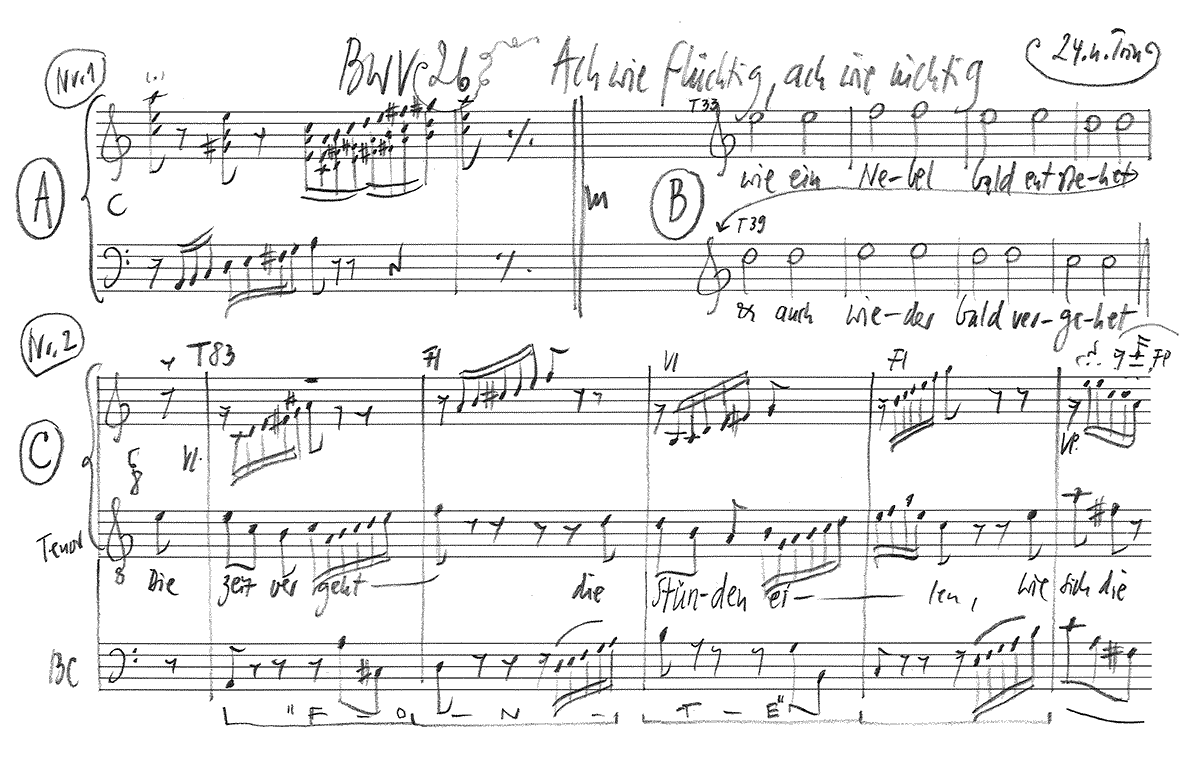

BWV 026 // For the Twenty-fourth Sunday after Trinity

(Ah, how fleeting, ah, how empty) for alto, tenor and bass, vocal ensemble, horn, flute, oboe I–III, bassoon, strings and continuo.

Composed for the Twenty-fourth Sunday after Trinity, the cantata “Ach wie flüchtig, ach wie nichtig” (Ah, how fleeting, ah, how empty) is pervaded by an atmosphere of late autumnal gloom and loss, in which the natural phenomena of the changing seasons are employed as unusually direct metaphors for the transience of life. Based on a hymn by Michael Frank (1652), the libretto’s interplay of rising mists, dismal downpours and fading flowers are skilfully interpreted to create a true “November” cantata of powerful musical imagery and concision.

Would you like to enjoy our videos ad-free? Subscribe to YouTube Premium now...

Workshop

Reflective lecture

Choir

Soprano

Leonie Gloor, Guro Hjemli, Damaris Nussbaumer

Alto

Jan Börner, Antonia Frey, Olivia Heiniger, Lea Scherer

Tenor

Clemens Flämig, Nicolas Savoy, Manuel Gerber

Bass

Fabrice Hayoz, Philippe Rayot, William Wood

Orchestra

Conductor

Rudolf Lutz

Violin

Renate Steinmann, Anaïs Chen, Sylvia Gmür, Martin Korrodi, Fanny Tschanz, Livia Wiersich

Viola

Susanna Hefti, Martina Bischof

Violoncello

Maya Amrein

Violone

Iris Finkbeiner

Oboe

Katharina Arfken, Stefanie Haegele, Dominik Melicharek

Bassoon

Susann Landert

Corno

Olivier Picon

Recorder/Flute

Claire Genewein

Harpsichord

Norbert Zeilberger

Organ

Norbert Zeilberger

Musical director & conductor

Rudolf Lutz

Workshop

Participants

Karl Graf, Rudolf Lutz

Reflective lecture

Speaker

Gerhard Schwarz

Recording & editing

Recording date

11/20/2009

Recording location

Trogen

Sound engineer

Stefan Ritzenthaler

Director

Meinrad Keel

Production manager

Johannes Widmer

Production

GALLUS MEDIA AG, Switzerland

Producer

J.S. Bach Foundation of St. Gallen, Switzerland

Librettist

Text No. 1, 6

Michael Franck (1609–1679)

Text No. 2–5

Arranger unknown

First performance

Twenty-fourth Sunday after Trinity,

19 November 1724

In-depth analysis

Although the introductory chorus is richly orchestrated with four vocal parts, three oboes and flute (plus a horn and strings that support the soprano part), the setting remains compact in style owing to its brief duration and economic doubling of voices. Throughout the movement, a swirling orchestral motive of ascending and descending passages propels the work forward like leaves in a gusty autumn wind. Through the sequences of brief, disrupted motives and text blocks, Bach conjures a drastic and all too fleeting image of the transient nature of human life.

The tenor aria, characterised by coloraturas and fruitless gestures, evokes the hastening of our mortal days through the image of “rushing waters”: here, the dominant transverse flute maintains the courtly tones of the introductory chorus while also functioning as a typical vanitas instrument. This is supplemented by a violin part, which sometimes participates in the virtuoso garlands of the tenor and the flute, but together with the continuo also fulfils an accompanying role. In the middle section of the extended da-capo aria, Bach realises a precise, naturalistic interpretation of the “breaking up” of raindrops, which represent the disintegration of all form and certainty in the face of death.

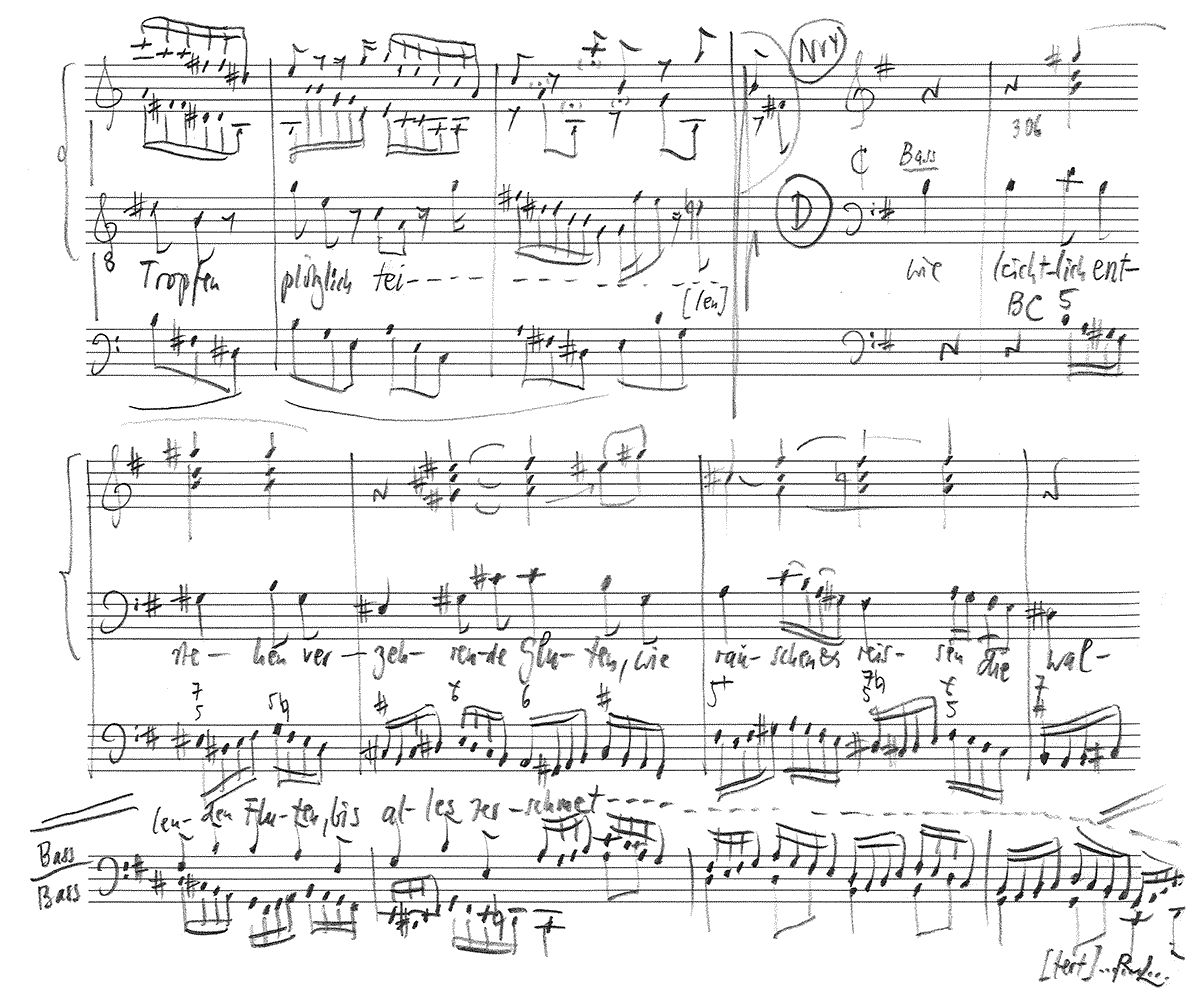

The alto recitative opens with an extreme ritardando, in which the melismatic rendering of “joy” suddenly transforms into “sadness” on a diminished chord. The movement is dominated by stark contrasts and powerful images, ere the prospect of the grave and “extinguishment” leads the vocal parts to descend to the lowest register. The following bass aria combines its sermon-like message with the dance form of a bourrée, evoking a hideous caricature of earthly elegance and craving for recognition. Here, the drooling tone of the obbligato oboes calls to mind a garishly made-up but long-doomed “Madame World”, whose gaudy “treasures” and crass “seductions” were ubiquitous in the sinful hubbub of life in Leipzig.

The second recitative, despite its brevity, delivers a truly devastating message: in the furore of the “final hour”, all will perish without hope or comfort. “Height’s foundation”, majesty and pretentions to godliness will all fall into oblivion. That the soprano was replaced at short notice by a tenor in this recording reflects the unpredictability of performance practice – an experience well familiar to baroque music directors, too.

The chorale, with its delayed cadences, retains the pessimistic character of the recitative and presents a memento mori of almost romantic expressiveness: only those who submit completely to God, will transcend death and receive the gift of eternal life.

Libretto

1. Chor

Ach wie flüchtig, ach wie nichtig

ist der Menschen Leben!

Wie ein Nebel bald entstehet

und auch wieder bald vergehet,

so ist unser Leben, sehet!

2. Arie (Tenor)

So schnell ein rauschend Wasser schiesst,

so eilen unser Lebenstage.

Die Zeit vergeht, die Stunden eilen,

wie sich die Tropfen plötzlich teilen,

wenn alles in den Abgrund schiesst.

3. Rezitativ (Alt)

Die Freude wird zur Traurigkeit,

die Schönheit fällt als eine Blume,

die grösste Stärke wird geschwächt,

es ändert sich das Glücke mit der Zeit,

bald ist es aus mit Ehr und Ruhme,

die Wissenschaft und was

ein Mensche dichtet,

wird endlich durch das Grab vernichtet.

4. Arie (Bass)

An irdische Schätze das Herze zu hängen,

ist eine Verführung der törichten Welt.

Wie leichtlich entstehen verzehrende Gluten,

wie rauschen und reissen

die wallenden Fluten,

bis alles zerschmettert in Trümmern zerfällt.

5. Rezitativ (Sopran*)

Die höchste Herrlichkeit und Pracht

umhüllt zuletzt des Todes Nacht.

Wer gleichsam als ein Gott gesessen,

entgeht dem Staub und Asche nicht,

und wenn die letzte Stunde schläget,

dass man ihn zu der Erde träget,

und seiner Hoheit Grund zerbricht,

wird seiner ganz vergessen.

*Ausgeführt durch Daniel Johannsen (Tenor)

6. Choral

Ach wie flüchtig, ach wie nichtig

sind der Menschen Sachen!

Alles, alles, was wir sehen,

das muss fallen und vergehen.

Wer Gott fürcht, bleibt ewig stehen.

Gerhard Schwarz

“Freedom from want and need – not a gift, but an effort”.

The cantata “Ach wie flüchtig, ach wie voidig” can be read as a call to hold material things in low esteem, but also as an appeal for moderation and restraint. Only the latter interpretation seems useful for our time – if one does not want to distance oneself from the goal that all people should at least have enough to live on.

The cantata “Ach wie flüchtig, ach wie voidig”, based on the song of the same name by the Thuringian poet Michael Franck, on the other hand, appeals to the metaphysical side of me as well as the secular, the philosophical and religious as well as the economic. The beginning of the song already contains everything that will then run through all six stanzas. On the one hand, it is about speed and transience, that is, about time. And on the other hand, it is about values, material but also immaterial, and their destruction and nullity.

The cantata suits a grey November Sunday. It was first performed 285 years ago yesterday. At that time, there were about 600 million people on earth, half as many as today in China alone; the level of prosperity in Central Europe was about 4 per cent of today’s standard, or one twenty-fifth; and life expectancy at birth – always for our latitudes – averaged somewhere between 25 and 35 years because of high infant mortality. Perhaps this explains part of the extraordinary fatalism and great melancholy of this text, a melancholy that goes much too far for me. Only the last chorale line gives hope, but even it is not for this world: “Wer Gott fürcht’, bleibt ewig stehen”. Despite a certain resemblance, this has nothing to do with the gripping and confident “In God we trust” that is written on every dollar bill.

One could almost say that there is a whiff of Buddhism wafting through this text, especially since in Frank’s song – in seven of the original thirteen stanzas – the transience not of wealth and prosperity, but of all that makes life worth living for most of us human beings, certainly for us Western and worldly people. If joy, beauty, strength, happiness, honour, knowledge and art are also void, then all that remains is the search for inner peace in complete asceticism and renunciation. Also surprisingly absent from the cantata are both morality – you may forgive me for using this old-fashioned word – and humanity. It is only about man’s relationship to God (and to death), not about the relationship between people, which only becomes pleasant and civilised thanks to morality. With respect, all this is perhaps suitable as a programme for a – very strict – monastic life, but not as a life plan for the average person.

Struggle to preserve prosperity

On the other hand, the text is very good as an impulse to think, to become thoughtful, which is not the same thing. Above all, of course, the bass aria, this little dance of death, challenged me and inspired some thoughts. From time to time, every economist must have doubts as to whether he is not dealing with a sphere of human thought and action “which, although of elementary necessity, is for that very reason of a lower kind. Primum vivere, deinde philosophari”, the ancient Romans said. And the Bible says: “Man does not live by bread alone.” Both seem somewhat more benevolent than the cantata text. After all, the economic has its place there. It is true that it does not have the dominant position that it is rapidly threatening to assume in human life, not only among those who are struggling to survive and of whom there are hundreds of millions in this world, but also among those who have become accustomed to prosperity and are struggling not to lose it. But still: the economic, the material has its place. Bread comes first, it is necessary for life, but not sufficient for life, man lives from it – just not from it alone.

The economy and those who represent it – shaping it as managers and reflecting on it as economists – are repeatedly treated with contempt and condescension. But although this is not entirely incomprehensible – even more so in the wake of the crisis – there is also a certain unworldly arrogance of satiety in it. For the contempt for the economy, the evocation of the transience of everything earthly, does not correspond to the behaviour of people. Goethe was right after all: “People press for gold, hang on to gold (…)”. People strive for more, they are almost insatiable, even the more failed among them. And with this striving they lay the foundation for the necessities of life and a modest existence, even the prosperity of many others.

It is this tension that we as human beings have to endure. On the one hand: if all people valued material things so little as expressed in the cantata, that is to say, if they humbled themselves with the absolute minimum, many people would not have enough to live on. Inequality is an unavoidable, inevitable part of reality, and it is only by striving for a lot that many – in a free market economy practically all – have enough to live on, that there is innovation and change. On the other hand, the excesses of this human striving for more, especially greed, do not make the individual happy; they are pathological and sickening addictions. They can even burden social coexistence and endanger cohesion. In this respect, the admonition of the cantata – “To hang one’s heart on earthly treasures / is a temptation of the foolish world” – is an appeal to moderation and moderation – in everything we humans strive for, i.e. wealth, certainly, but also power, beauty, fame, knowledge and even art.

Moral quality of the market economy

One could now object – and many will do so nowadays, it is almost part of the zeitgeist – that our economic system, in which we live, unleashes and fosters this exaggerated striving for more and more, making people’s thoughts revolve only around everything earthly, money and much that can be bought with money or that they think they can buy, and in the process damaging their souls. But this interpretation is wrong. The open, liberal economic order does not promote negative qualities and attitudes, it just does not suppress them; it simply allows the whole diversity of human motives, including aberrations and exaggerations. Whatever the motives of people, as long as they do not harm others, their actions almost always benefit the overall good in some way. Private vices such as avarice, greed and craving for favours become public benefits.

Because many critics mistakenly blame people’s vices on the order that allows them rather than prevents them, they become completely blind to the extraordinary moral quality that characterises society based on the market economy. This is fourfold.

First, modern, “capitalist” societies are the least coercive and least violent in human history; this is what makes morality possible in the first place, for only action in freedom can claim moral quality.

Secondly, despite an exuberant welfare state, these societies are still mainly based on people taking responsibility for themselves and their own and not living at the expense of others.

Thirdly, open, competitive economies do not simply unleash the simple desire for profit, they also unleash the creative forces without which our modern world would be inconceivable.

And, fourthly, there is no doubt that freedom – as well as personal responsibility – is a high value per se.

If one tries to read the cantata in an enlightened way and interpret it in a modern way, beyond metaphysics, one could also understand it as just that, namely as a rejection of any utilitarianism. The superficial, relatively clearly definable and operable goals such as wealth, happiness, power or honour must take a back seat to higher values. For the people of the Baroque there was only one such higher value, namely God. Although I certainly do not want to equate the idea of freedom with God, there is a parallel with the thesis I have always upheld that we should never defend the market economy and a liberal social order merely for the sake of utility, but that freedom is such a precious value that we should even sacrifice prosperity and well-being to it if necessary. Fortunately, economic freedom also brings prosperity, so that we as societies have never had to pass this litmus test and never will. The millions of people, on the other hand, who fled from totalitarian regimes, giving up all their possessions and risking their lives, made this decision for themselves and valued freedom so highly that they were prepared to give up a lot and risk everything.

Deceptive land of milk and honey

One last thing: Franklin D. Roosevelt became famous with his catalogue of the four freedoms, freedom of speech, freedom of religion, freedom from fear and freedom from material hardship, which Norman Rockwell has so magnificently and pathetically depicted.4 Who would not be moved by this vision? But if one thinks more carefully, one quickly realises that the latter, freedom from material need, is a land of milk and honey conception. Only there do the restrictions on enjoyment based on the natural scarcity of goods completely disappear. Only there does that positively defined freedom prevail, which is probably not even appealing because of boredom, but above all completely unrealistic. In the real world, on the other hand, “freedom from want” always requires effort, it is not given to us as a gift. In the short term, it can perhaps be secured through redistribution. But in the medium term, that will never be a solution. It requires entrepreneurship, creativity, profits, the accumulation of capital and the constant increase of productivity. But in a way, extreme frugality also leads to the feeling of “freedom from want” – perception is reality. When one reduces one’s needs, one is quickly free of the striving for more, then that contentment returns in which one desires nothing.

In this respect, the message of the cantata could be seen not so much as a counterweight to the world of economics, the “creation of value”, but rather as a complement. In its fight against want, the market economy starts on the supply side; productivity and innovation create wealth and thus liberate people from many long-prevailing, natural conditions of scarcity. The message of the nothingness of everything earthly, on the other hand, starts on the demand side: those who want little, those who are content with little, also become free of want and need. And so, as a complement to life and not as a repression of it, as ordinary mortals live it, there is probably a deep meaning and a help in life in the melancholy “Oh how fleeting, oh how futile”, also and especially for us people of the 21st century, who easily threaten to lose the centre, the anchor, in the busyness and prosperity.

Literature

– Angus Maddison, The World Economy, A Millenial Perspective, Paris 2001

– Bernard Mandeville, The Bee Fable or Private Vices, Public Advantages, Frankfurt 2006

– Wilhelm Röpke (ed.), Marktwirtschaft ist nicht genug. Collected Essays, Leipzig 2009

This text has been translated with DeepL (www.deepl.com).