Freue dich, erlöste Schar

BWV 030 // For the Nativity of St. John the Baptist

(Joyful be, O ransomed throng) for soprano, alto, tenor and bass, vocal ensemble, transverse flute I+II, oboe I+II, oboe d’amore, violino concertato, strings and basso continuo

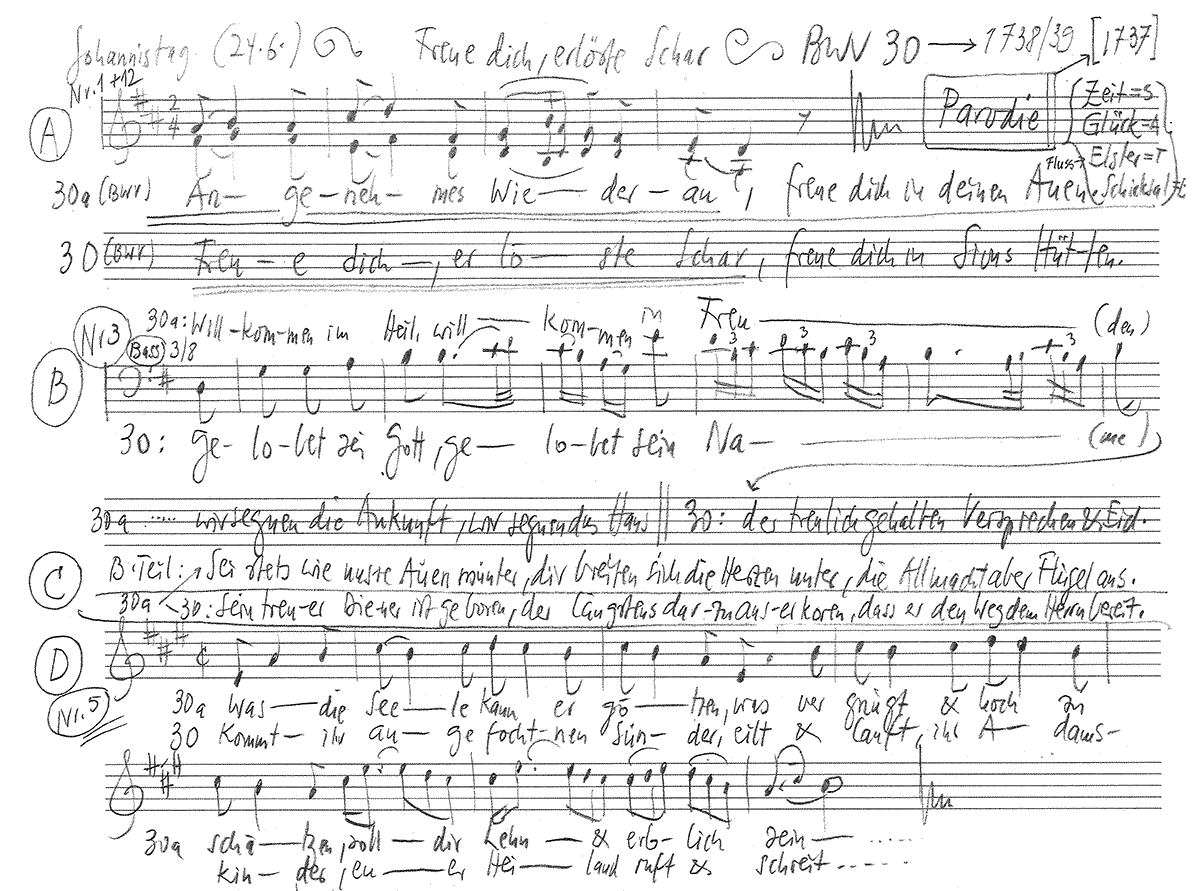

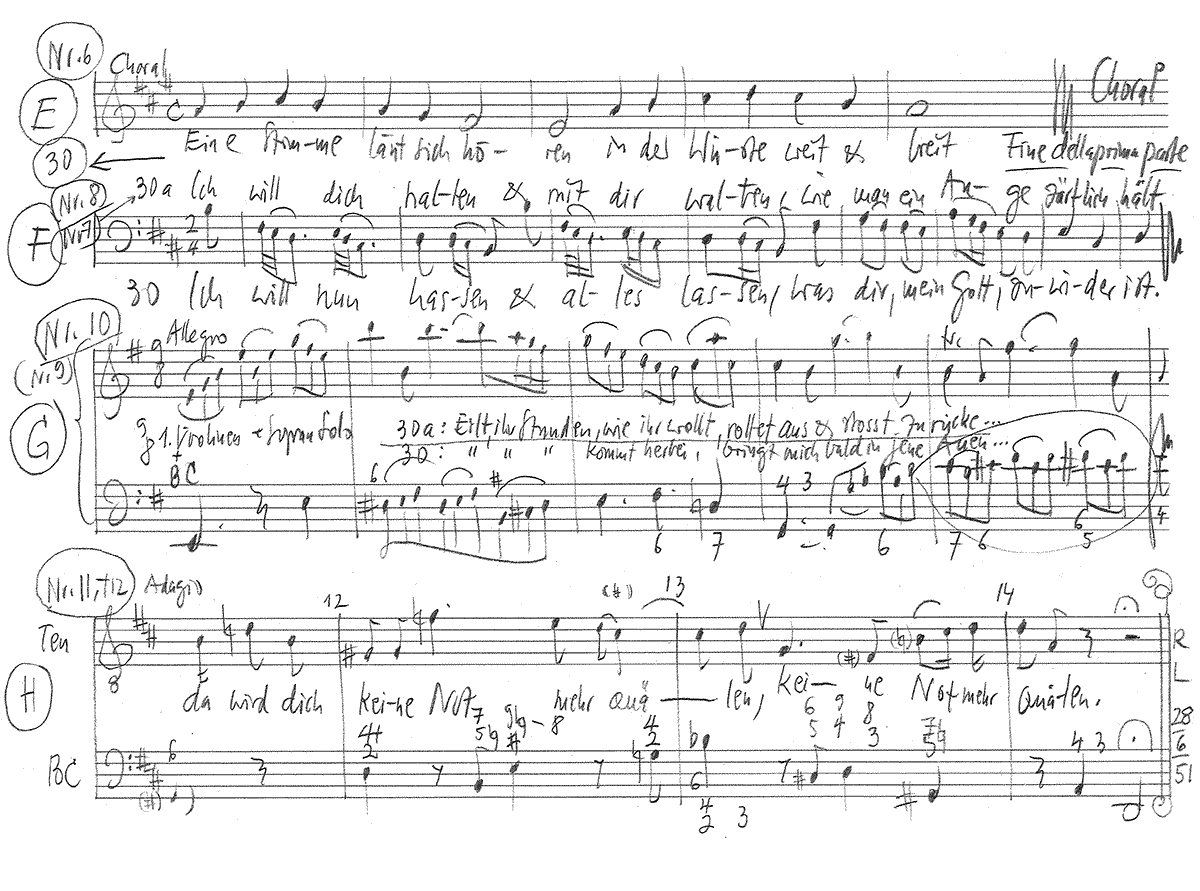

Recent research has corroborated the long-held assumption that Bach composed the greater part of his Leipzig cantatas during his first years there as Thomascantor. From 1730 onward, he then parodied many of these works, reorganizing them in new compilations such as the Christmas Oratorio and the four short masses BWV 233 to 236, thus maximizing the fruits of his earlier labours. The St John the Baptist cantata “Freue dich, erlöste Schar” (Joyful be, O ransomed throng) BWV 30 is one parody composition of this time, and despite being one of Bach’s latest sacred works, it is based on a homage cantata “Angenehmes Wiederau” (O most charming Wiederau), which he composed in 1737 for the Saxon court official J. C. Hennicke.

Would you like to enjoy our videos ad-free? Subscribe to YouTube Premium now...

Workshop

Reflective lecture

Choir

Soprano

Susanne Seitter, Olivia Fündeling, Mirjam Berli, Noëmi Tran Rediger, Noëmi Sohn Nad, Alexa Vogel

Alto

Jan Börner, Antonia Frey, Katharina Jud, Damaris Rickhaus, Francisca Näf

Tenor

Christian Rathgeber, Manuel Gerber, Marcel Fässler, Nicolas Savoy

Bass

Philippe Rayot, Tobias Wicky, Oliver Rudin, Daniel Pérez, Fabrice Hayoz

Orchestra

Conductor

Rudolf Lutz

Violin

Plamena Nikitassova, Dorothee Mühleisen, Sonoko Asabuki, Christine Baumann, Claire Foltzer, Elisabeth Kohler, Christoph Rudolf

Viola

Martina Bischof, Sarah Krone, Katya Polin

Violoncello

Maya Amrein, Hristo Kouzmanov

Violone

Iris Finkbeiner

Oboe

Andreas Helm, Kerstin Kramp

Oboe d’amore

Andreas Helm

Bassoon

Susann Landert

Transverse flute

Tomoko Mukoyama, Renate Sudhaus

Organ

Nicola Cumer

Harpsichord

Jörg Andreas Bötticher

Musical director & conductor

Rudolf Lutz

Workshop

Participants

Karl Graf, Rudolf Lutz

Reflective lecture

Speaker

Rolf Soiron

Recording & editing

Recording date

26/06/2015

Recording location

Trogen

Sound engineer

Stefan Ritzenthaler

Director

Meinrad Keel

Production manager

Johannes Widmer

Production

GALLUS MEDIA AG, Switzerland

Producer

J.S. Bach Foundation of St. Gallen, Switzerland

Librettist

Text No. 1–5, 7–12

Poet unknown,

probably Christian Friedrich Henrici, known as Picander

Text No. 6

Johann Olearius, 1671

First performance

24 June 1738 or on St John’s Day in one of the following years

In-depth analysis

Although the sacred version eschews the trumpets and timpani of the original, the secular origins of the introductory chorus remain plain to hear. The movement has no prelude, opening instead with powerful acclamations from the choir. The music strongly resembles a dance suite, and its syncopated rhythms, rondo-style structure and transparent orchestration suggest that Bach, despite being in his fifties, was surprisingly willing to accommodate the increasing demand for a “natural” compositional style.

The Wiederau homage cantata, in accordance with the semi-staged structure of such serenades, features diverse allegorical characters, each of whom are assigned a recitative and an aria fitting to their role. In the sacred parody, too, each recitative and aria forms a unit, with the first recitative describing the shift from Mosaic law to the baptismal covenant, followed by an aria for bass, strings and continuo, whose text “All praise be to God” alludes to the biblical Canticle of Zacharias, the father of John the Baptist. This movement’s powerful minuet style lends its praise of God a priestly dignity in which the “Destiny” character of the original cantata has essentially been preserved.

The following pair of movements, too, can hardly deny their relationship to the character of “Joy” from the original cantata. The recitative, in fitting noble style, addresses John as the herald of “King” Jesu, while the ensuing alto aria, with its gallant melodic style and distinctive instrumentation of transverse flute and muted strings, seems startlingly modern for Bach. In the parody, the subservient delight of the Hennicke cantata is skilfully transformed into Jesus’ wooing of the “sorely tempted sinners” and “Adam’s children”. This is followed by a chorale, “Eine Stimme lässt sich hören”, inserted for the sacred parody only, which serves to break the cantata into the two-part form required to frame the sermon.

While the Wiederau cantata featured a secco-recitative, Bach favoured a more artistic form for the sacred parody, employing an accompagnato for bass and two oboes that gracefully illuminates the New Covenant lauded in the text. The aria, by contrast, embodies a drastic shift in affect from trust in earthly destiny to emphatic rejection of worldly pleasures, in emulation of Christ. In the next double movement, the wording and affect remain closer to the secular original. While the soprano recitative in both the secular and sacred versions emphasises the constancy of courtly order and observance of the baptismal vow respectively, the soprano aria reinterprets the words “haste, ye hours” as a symbol of longing desire – underscored by an insistent 9⁄ 8-metre and lyrical E minor key – to see the promised pastures of paradise.

The tenor recitative retains the welcoming gesture of the Wiederau banquet music, but uses it here to evoke enraptured anticipation of heaven, here the repetition of the introductory chorus rounds out a highly unusual parody composition that may well have caused many a Leipzig critic a moment’s pause.

Libretto

Erster Teil

1. Chor

Freue dich, erlöste Schar,

freue dich in Sions Hütten!

Dein Gedeihen hat itzund

einen rechten festen Grund,

dich mit Wohl zu überschütten.

2. Rezitativ (Bass)

Wir haben Rast,

und des Gesetzes Last

ist abgetan.

Nichts soll uns diese Ruhe stören,

die unsre liebe Väter oft

gewünscht, verlanget und gehofft.

Wohlan,

es freue sich, wer immer kann,

und stimme seinem Gott zu Ehren

ein Loblied an,

und das im höhern Chor,

ja, singt einander vor!

3. Arie (Bass)

Gelobet sei Gott, gelobet sein Name,

der treulich gehalten Versprechen und Eid!

Sein treuer Diener ist geboren,

der längstens darzu auserkoren,

daß er den Weg dem Herrn bereit’.

4. Rezitativ (Alt)

Der Herold kömmt und meldt den König an,

er ruft; drum säumet nicht,

und macht euch auf

mit einem schnellen Lauf,

eilt dieser Stimme nach!

Sie zeigt den Weg, sie zeigt das Licht,

wodurch wir jene selge Auen

dereinst gewißlich können schauen.

5. Arie (Alt)

Kommt, ihr angefochtnen Sünder,

eilt und lauft, ihr Adamskinder,

euer Heiland ruft und schreit!

Kommet, ihr verirrten Schafe,

stehet auf vom Sündenschlafe,

denn itzt ist die Gnadenzeit!

6. Choral

Eine Stimme läßt sich hören

in der Wüsten weit und breit,

alle Menschen zu bekehren:

Macht dem Herrn den Weg bereit,

machet Gott ein ebne Bahn,

alle Welt soll heben an,

alle Täler zu erhöhen,

daß die Berge niedrig stehen.

Zweiter Teil

7. Rezitativ (Bass)

So bist du denn, mein Heil, bedacht,

den Bund, den du gemacht

mit unsern Vätern, treu zu halten

und in Genaden über uns zu walten;

drum will ich mich

mit allem Fleiß

dahin bestreben,

dir, treuer Gott, auf dein Geheiß

in Heiligkeit und Gottesfurcht zu leben. p>

8. Arie (Bass)

Ich will nun hassen

und alles lassen,

was dir, mein Gott, zuwider ist.

Ich will dich nicht betrüben,

hingegen herzlich lieben,

weil du mir so genädig bist.

9. Rezitativ (Sopran)

Und ob wohl sonst der Unbestand

den schwachen Menschen ist verwandt,

so sei hiermit doch zugesagt:

So oft die Morgenröte tagt,

so lang ein Tag den andern folgen läßt,

so lange will ich steif und fest,

mein Gott, durch deinen Geist

dir ganz und gar zu Ehren leben.

Dich soll sowohl mein Herz als Mund

nach dem mit dir gemachten Bund

mit wohlverdientem Lob erheben.

10. Arie (Sopran)

Eilt, ihr Stunden, kommt herbei,

bringt mich bald in jene Auen!

Ich will mit der heilgen Schar

meinem Gott ein’ Dankaltar

in den Hütten Kedar bauen,

bis ich ewig dankbar sei.

11. Rezitativ (Tenor)

Geduld, der angenehme Tag

kann nicht mehr weit und lange sein,

da du von aller Plag

der Unvollkommenheit der Erden,

die dich, mein Herz, gefangen hält,

vollkommen wirst befreiet werden.

Der Wunsch trifft endlich ein,

da du mit den erlösten Seelen

in der Vollkommenheit

von diesem Tod des Leibes bist befreit,

da wird dich keine Not mehr quälen.

12. Chor

freue dich in Sions Auen!

Deiner Freude Herrlichkeit,

deiner Selbstzufriedenheit

wird die Zeit kein Ende schauen.

Freue dich, geheilgte Schar,

freue dich in Sions Auen!

Deiner Freude Herrlichkeit,

deiner Selbstzufriedenheit

wird die Zeit kein Ende schauen.

Rolf Soiron

From Wiederau to Omega

The cantata “Freue Dich, erlöste Schar” (Rejoice, Redeemed Flock) and the circumstances of its composition provoke the question of whether that which held the world together at its innermost core at that time still does, and whether we would not need this in order for all that we do to have its meaning.

The church festival of St John, the birthday of John the Baptist, exactly six months before Christmas, once had a much higher significance in the annual cycle and customs, also in Leipzig. On this day in 1738, the congregation therefore listened carefully to what the cantor recited to them during the service. They were obviously not bothered by the fact that he had not invented the festive music this time, but had used it once before, albeit on a completely different occasion. And even the church superiors, who could occasionally be petty, did not say a word about the fact that the first version had not been performed in honour of a relative of Jesus and a high saint, but of a man of the Dresden court, where things were not quite as sinful as they were with Herod, but not like in a Sunday school either. Now, on St John’s Day, the church resounded with the sounds of joy at the new ways preached by John; at the time, at the inauguration of the nearby manor of Wiederau, the music had paid homage to a contemporary who embodied something quite different. It was well known that Johann Christian Graf von Hennicke practised neither rethinking nor repentance, as John the Baptist demanded, nor did he dress in camel’s hair or feed on locusts. Spirit and character were not attributed to the man of power and success, but the energy to assert himself, cunning, lack of conscience, vanity and greed. From humble beginnings he had made it – sometimes by crooked means and with services that were kept secret – to wealth, nobility and just now to his first ministerial office. Bach’s music had sung the praises of this man, his world and his position in the park of Wiederau. Now, a few months later, on the Feast of the Baptist, in the cantata “Rejoice, Redeemed Flock” (BWV 30), the same harmonies sang of spiritual success and reward, of making straight the crooked paths, called “stray sheep” from their “sleep of sin” and promised to “hate and forsake all that is abhorrent to thee, my God”. What a contrast! But just the same: No one was bothered by it.

That was almost three centuries ago. Hennicke has long been forgotten. But it is striking how similar his reputation is to that of many of the greats of business today, deserved or undeserved. They too are said to know how to assert themselves, to be smart and professional. But again and again, those other attributes come up: lack of spirit, conscience and character, selfishness focused only on their own success, greed, short rather than long-sightedness. Responsible interest beyond accounts and stock prices is hardly granted to them. This image of our business leaders is so deep-seated that it may explain the outrage that hit the head of Goldmann Sachs when he remarked almost casually but publicly that in his profession he was really only doing “God’s work”. What an outcry went around the world! That a temple servant of Mammon, of all people, should make himself a worker in God’s vineyard – that could not be. In fact, Lloyd Blankfein’s formulation shortly after the crisis was not too clever. But perhaps he was just trying to say that the financial system was also part of a larger whole and that he himself simply played the role he was supposed to play in it. This thought was not so absurd – but it was not wanted to be heard!

What would have happened if Bach had said in his time that as a musician he was only doing God’s work? No one would have made a fuss! Not even when the church music for the forerunner of Christ was first – paid for! – had been used for an unscrupulous man of power, and not even then, when – as everyone knew – the pious Musikus of St.Thomas liked to consort with powerful people and courts, appreciated title teachings and always made sure that the cash was right. When he placed Soli Deo Gloria above his scores, it provoked no one – he was taken for doing God’s work. For explicitly and implicitly, people knew about his world view, in which God had not only created the cosmos, but created it perfectly. Thus the universe was harmonious and from it came the musical harmonies. To think oneself into this connection between cosmos and music was the profession of the musician, as one did in the “Corresponding Society of Musical Sciences”, where Bach was a member. Music that came from God’s harmonies necessarily led back to Him. To penetrate God’s laws of harmony in order to create ever better music, sacred and secular, was Bach’s vocation, calling – and God’s work!

Bach was not the only one who thought this way. For many at that time, science was the finger pointing to God and his work, or more: the metaphor for God as Alpha and Omega. Leibniz was dead, but the thought system of this great son of the city stood firm: the ever deeper study of nature, the world and the universe led to an ever deeper insight into the fundamental ideas of God. Newton was also avidly read and taught in Leipzig, and he too had always insisted that his physical and mathematical principles ultimately only traced the construction ideas of the creator of world mechanics. Others in other fields thought and worked in the same way. This formed a zeitgeist with a fixed point that made research, creation and work parts of a God-willed whole – and each individual’s own contribution to God’s work!

This is no longer the case. We have penetrated deep into nature, history, the world and the universe, deeper than Leibniz, Newton and the others could have dreamed. But along the way we have lost the one who founded everything and to whom everything pointed. Man has emancipated himself and taken the world and the universe into his own hands in place of the One who once held everything together. What was once One has thereby dissolved into rationality that is logical in and of itself, but parallel and unconnected. The old questions of where the whole comes from, what holds the world together at its core, what is ultimate and supreme, have become too difficult or are asked less and less – because irrational or no longer in keeping with the times – and what we do has thus lost the chance of being part of God’s work.

This also and especially applies to what we do and think economically. The image of the Invisible Hand guiding the markets at least reminded us that someone once did that. Today, God or a Last, Highest One simply no longer appears in economic discourse. Beyond what is tangible and visible, the economy no longer seems to need a source and a goal. Those who lack this are free to find it privately – but only privately. This ignores the fact that Homo sapiens has been shaped over thousands of years by not one, but two strands of experience. On the one hand, there was the daily effort to procure the necessities of life. On the other hand, there has always been the search for explanations of what governed the world and life in the longue durée and beyond our short horizons. This strand has broken off, while we pursue the economic one more than ever. But it is certainly no longer a metaphor of a path to God.

Of course it is good and right, dignum et justum, that the transcendental quest has become more demanding. For of course the images of the old man with his white beard as the incarnation of the whole, and of what creation is meant to be, are no longer sufficient. Of course, we would make it too easy for ourselves with new high authorities who direct things instead of us and from whom we only have to ask for what we lack. There are enough gods and idols that make people the scourge of other people. The freedom to decide what is most important to you must also remain sacred. But to forego the search for answers as to what it is all about, what our contribution is and what is expected of us, would be fatal. We would only know better and better how everything works, but less and less what for. Vaclav Havel saw what this leads to: The crises of our time have their true roots in the modern loss of all metaphysical certainty! To this Peter Bichsel added one of his memorable sentences: “We need God so that everything that is, is not everything.”

This has also troubled economic thinkers. One of them was Keynes. When he, the economist, was asked for recipes to get out of the Great Crisis, he unexpectedly warned: “The day is not far off when the Economic Problem will take the back seat where it belongs (…) and the arena of our heart will be re-occupied by our real problems, the problems of real life and of human relations, of creation and behaviour and religion.” A similar track was laid out by an economist of a completely different stamp, Wilhelm Röpke: “Although man is first and foremost a homo religiosus, we have made the increasingly desperate attempt to get along without God and to put man, his science, his art, his technology and his state, in their remoteness from God, indeed godlessness, in his place in a self-important manner”. Like John the Baptist, Röpke pleaded for a rethink: the “what for” of economic activity should be given as much importance as the omnipresent “how”.

It is not about sanctimoniously lowering one’s eyes to the questions at hand, not about new images on altars or new catechisms. It is not about larmoyant confession. It is about interested participation of thinkers and leaders in the search for answers to what our contribution is to the duration and to the whole, where it comes from and where it is going. At the centre should be the search for the point Omega, as Teilhard de Chardin called the fixed point towards which everything steers. Economy is indispensable. It shapes the necessities of life. But those who create need orientation – a point, Omega, or whatever we want to call it. Money, numbers and indices alone cannot provide this, which is why it would be good for the economy and economics to be re-embedded in philosophical reflection. Of course, this does not solve the countless small, large and big tasks that await us in companies, countries and the world. The search for Omega does not provide that. But it shows directions, beyond the day, beyond supply and demand, and makes what the economy does and should do more readable than it is at present. Hennicke, Blankfein and all of us would be perceived and accepted as responsible stewards of the talents entrusted to us – and our work as God’s work. As the cantata’s opening chorus sings, our daily efforts would indeed create “a right solid ground” to “shower us with good”.

This brings us back to Bach and his music. It does not need all these many words to be God’s work, whether it sounds for the Baptist, for his less holy namesake, Count Johannes Hennicke, or for us today. Our ears hear it, our minds experience it, and our souls are touched by it.

This text has been translated with DeepL (www.deepl.com).