Wo soll ich fliehen hin

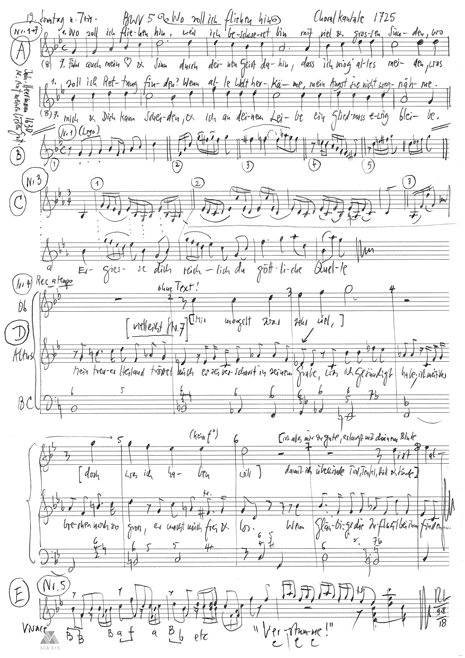

BWV 005 // For the Nineteenth Sunday after Trinity

(Where shall I refuge find) for soprano, alto, tenor and bass, vocal ensemble, oboe I+II, tromba da tirarsi, strings and basso continuo

Would you like to enjoy our videos ad-free? Subscribe to YouTube Premium now...

Workshop

Reflective lecture

Choir

Soprano

Susanne Seitter, Noëmi Sohn Nad, Noëmi Tran-Rediger, Alexa Vogel, Anna Walker, Mirjam Wernli-Berli

Alto

Jan Börner, Antonia Frey, Liliana Lafranchi, Alexandra Rawohl, Damaris Rickhaus

Tenor

Clemens Flämig, Tobias Mäthger, Sören Richter, Walter Siegel

Bass

Fabrice Hayoz, Valentin Parli, Philippe Rayot, Jonathan Sells, Tobias Wicky

Orchestra

Conductor

Rudolf Lutz

Violin

Eva Borhi, Lenka Torgersen, Peter Barczi, Christine Baumann, Dorothee Mühleisen, Ildikó Sajgó

Viola

Martina Bischof, Sarah Mühlethaler, Katya Polin

Violoncello

Maya Amrein, Daniel Rosin

Violone

Markus Bernhard

Oboe

Katharina Arfken, Elise Nicolas

Tromba da tirarsi

Patrick Henrichs

Bassoon

Susann Landert

Organ

Nicola Cumer

Harpsichord

Thomas Leininger

Musical director & conductor

Rudolf Lutz

Workshop

Participants

Niklaus Peter Barth, Rudolf Lutz

Reflective lecture

Speaker

Anselm Grün

Recording & editing

Recording date

16.08.2018

Recording location

Teufen AR (Schweiz) // Kirche Teufen

Sound engineer

Stefan Ritzenthaler, Nikolaus Matthes

Director

Meinrad Keel

Production manager

Johannes Widmer

Production

GALLUS MEDIA AG, Switzerland

Producer

J.S. Bach Foundation of St. Gallen, Switzerland

Librettist

Text

Johann Heermann

First performance

Cantata for the 19th Sunday after Trinity,

15 October 1724

In-depth analysis

The composition “Wo soll ich fliehen hin” (Where shall I refuge find, BWV 5), based on the hymn of the same name by Johann Heermann, was composed for the 19th Sunday after Trinity in 1724 and thus belongs to Bach’s second Leipzig cycle of cantatas. The fact that the original score, today preserved at the British Library, once belonged to the cosmopolitan writer Stefan Zweig, who, after becoming a refugee, broke under the totalitarian events of his time, may be seen as a poignant note in the history of its reception.

The introductory chorus is a nervous perpetuum mobile whose urgent character evokes a pressing sense of existential angst; here, mere humans are powerless to stop the merciless drama of fate unfolding in Bach’s precisely chiselled phrases. The ascending head motive pervades throughout the string and oboe ensemble writing, thus giving ongoing prominence to the first line of the chorale – even as the inverted figures simultaneously enhance the sense of disorientation. The lower voices, which accompany the broad soprano phrases, echo the hectic gestures of the orchestra; by doubling the cantus line, the slide trumpet reinforces the hymn’s gloomy tone of judgement and heightens the drama to a level of despairing earnestness.

The bass recitative presents a sobering conclusion: in the vein of the Old Testament, body and soul are so ravaged by sin that humankind can do naught but appear impure and damned in the eyes of God. Then comes a sonorous reminder that only Christ’s “holy blood” guarantees deliverance: in the open sea of the Saviour’s wounds, the faithful can cleanse themselves of the stain of sin.

The liberating potential of this severe lesson is then revealed in the enchanting tenor aria. Over a gentle bass line, the elegantly descending four-note motive of the obbligato part transforms the river of mercy, springing from the godly source, into a warmly flowing balsam that inspires the tenor soloist to a song of enraptured gratitude. The darkly shimmering E-flat major tonality bathes the whole aria in a both strange and familiar light, in which the cruel blood sacrifice becomes a healing event in and of itself. Throughout the setting, the string part (which despite its low register was probably conceived for the violin) remains continuously present, much in the manner of an engaged partner in a conversation.

The reason why the following alto recitative is marked “a tempo” becomes clear only in the second bar – but for that, all the more memorably. Indeed, the recitative text on the death of Jesus is enhanced by a rendition of the chorale melody in the oboe part, elevating the setting in a most moving way. Once again, Bach weaves his subtly ingenious craft to musically meld the themes of sacrificial blood and crucifixion with solace and forgiveness in a human context.

This fortification of the spirit finds defiant expression in the bass aria. Set with an energetic dance-like gesture and scored for a radiant trumpet with string and oboe accompaniment, the hosts of hell – already weakened by Christ’s sacrifice on the cross – are again vanquished in open battle. Here, the soloist steps centre stage like the triumphant hero of a baroque opera; his aria, supported by a trusty orchestral accompaniment and culminating in the motto of “Es ist in Gott gewagt” (For this in God I dare), certainly numbers among the most rewarding of Bach’s bass solos.

After this climax, the fact that the composer and librettist revert to a more subdued tone belongs to the most captivating details of this masterly cantata. “Ich bin ja nur das kleinste Teil der Welt” (I am, indeed, the world’s mere smallest part): with these words of deepest humility and music of nigh-whispered rhetorical heights, the soprano recitative evokes once again the redemptive power of the purifying blood – an act of undisguised faith that was no doubt ideal for the childlike timbre of Leipzig’s descant boy choristers.

In keeping with traditional form, the cantata closes with a four-part chorale – a standard compositional duty for Bach. Nonetheless, the power and strength that the composer draws from this routine setting is heard note for note throughout the verse. In this movement, the peril and duress of the opening chorus have given way to a yearning energy that inspired the spontaneous organ interlude featured in this recording.

Libretto

1. Choral

Wo soll ich fliehen hin,

weil ich beschweret bin

mit viel und grossen Sünden,

wo soll ich Rettung finden?

Wenn alle Welt herkäme,

mein Angst sie nicht wegnähme.

2. Rezitativ – Bass

Der Sünden Wust hat mich nicht nur befleckt,

er hat vielmehr den ganzen Geist bedeckt,

Gott müsste mich als unrein von sich treiben;

doch weil ein Tropfen heilges Blut

so grosse Wunder tut,

kann ich noch unverstossen bleiben.

Die Wunden sind ein offnes Meer,

dahin ich meine Sünden senke,

und wenn ich mich zu diesem Strome lenke,

so macht er mich von meinen Flecken leer.

3. Arie – Tenor

Ergiesse dich reichlich, du göttliche Quelle,

ach, walle mit blutigen Strömen auf mich.

Es fühlet mein Herze die tröstliche Stunde,

nun sinken die drückenden Lasten zu Grunde,

es wäschet die sündlichen Flecken von

sich.

4. Rezitativ – Alt

Mein treuer Heiland tröstet mich,

es sei verscharrt in seinem Grabe,

was ich gesündigt habe;

ist mein Verbrechen noch so gross,

er macht mich frei und los.

Wenn Gläubige die Zuflucht bei ihm finden,

muss Angst und Pein

nicht mehr gefährlich sein

und alsobald verschwinden;

ihr Seelenschatz, ihr höchstes Gut

ist Jesu unschätzbares Blut,

es ist ihr Schutz vor Teufel, Tod und Sünden,

in dem sie überwinden.

5. Arie — Bass

Verstumme Höllenheer,

du machst mich nicht verzagt!

Ich darf dies Blut dir zeigen,

so musst du plötzlich schweigen,

es ist in Gott gewagt.

6. Rezitativ — Sopran

Ich bin ja nur das kleinste Teil der Welt,

und da des Blutes edler Saft

unendlich grosse Kraft

bewährt erhält,

dass jeder Tropfen, so

auch noch so klein,

die ganze Welt kann rein

von Sünden machen,

so lass dein Blut

ja nicht an mir verderben,

es komme mir zu gut,

dass ich den Himmel kann ererben.

7. Choral

Führ auch mein Herz und Sinn

durch deinen Geist dahin,

daß ich mög alles meiden,

was mich und dich kann scheiden,

und ich an deinem Leibe

ein Gliedmass ewig bleibe..

Anselm Grün

Where shall I flee to

The cantata “Wo soll ich fliehen hin” is based on the biblical text from Matthew 9:1-8. In this text, Jesus heals the paralytic with the words, “Get up, take your stretcher and walk!” I would interpret the text as Jesus encouraging me to take my inhibitions and paralysis under my arm and get up, get out of the spectator role and take my life into my own hands.

When I read the text of the cantata “Wo soll ich fliehen hin”, I was initially disappointed. I thought it was the typical fixation on guilt characteristic of Martin Luther, whose most important question was: “How do I get a merciful God?” But then I realised that I must not develop a theory of the atonement for our sins from the many images of blood. Rather, the blood is an image of love. We speak of the lifeblood we give for others. Jesus himself says of himself, “There is no greater love than this, that a man lay down his life for his friends.” (John 15:13) And John describes to us how blood and water flowed from the open heart of Jesus on the cross. This is a picture of Jesus’ love flowing into the whole world. The world is not only marked by sin and guilt, by the wickedness of the wicked, but it is permeated by the love of Jesus. This gives us a new perspective on ourselves and on our world.

God does not need the death of his Son to forgive. God forgives because he is God, because he is merciful. But – as the Protestant theologian Paul Tillich says – we feel unacceptable in our guilt. That’s when we need such powerful images as the blood that is shed for us to overcome our inability to believe in forgiveness. The image wants to enable us to accept ourselves despite all our unacceptability because God accepts us unconditionally in Jesus Christ. When we see the words of the cantata as images, we feel free. Martin Heidegger once said, “Looking leads to freedom, hearing to security.” I look at the pictures in all freedom. Hearing brings us together. It connects us and gives us the feeling of being carried, of being secure.

When I listen to the music with which Johann Sebastian Bach set the words to music, I hear the love that permeates me in the music. And I feel secure in a love that is greater than my guilt, than my inability to accept myself. We need good images that are imagined in us. For many people are unwell because the images they have of themselves do not correspond to their reality. For Plato, education consists of imagining good images. In listening to the cantata, the images of words and music form in us to bring us into contact with the original and pure image that God has made of each of us.

St. Augustine wrote his own theology of music. In it he writes that music brings us into contact with the love that is within us, but from which we are often enough separated by the cares that beset us. And Augustine approvingly quotes Plato, who thinks that “choros” comes from “chara = joy”. By listening to the music of Bach, we feel the love that flows at the bottom of our soul, and the joy that is often enough buried rises into our consciousness. When we listen to the music of this cantata, we do not need to believe at all, faith happens. Bach does not ask us to rejoice in our salvation. In listening to the music, joy arises in us about our salvation, about the fact that we are unconditionally loved by God, against all the self-reproaches and self-recriminations with which we often enough make life difficult for ourselves.

Bach wrote beautiful music. Plato says: beauty begets love and love makes beauty known. The Russian poet Dostoevsky once said, “Beauty will save the world. Beauty will heal the world.” And he thinks he has to look at the beauty of the Sistine Madonna at least once a year to be able to cope with his life. So we can say: we must listen to a Bach cantata at least once a month in order to be able to live our everyday life with its tribulations joyfully and confidently from the beauty of the music. Bach’s beautiful music does not take us to an ideal world. In his music, the abysses of man, his despair and his hardships also become audible. But music transforms these abysses. Beauty transforms and heals.

We are not oppressed today by the fear that we might sin and transgress the commandments of God. But we certainly know the fear that we will miss our lives, that our lives will not succeed. And we know the fear that we are not enough. I know many people who feel: I am not good enough. I accompanied a psychologist who gives courses for managers. But after every course he feels: I am not good enough. The course was not good enough. As a child, he always had the feeling: I don’t meet my parents’ expectations. Later he felt: I am not good enough as a father. I am not enough as a husband. The expectations that the media arouse in us, that we always have to be perfect, always successful, always cool, lead to more and more people feeling that they are not enough. Into this fear we should let the words and the music of this cantata penetrate. The words and the music tell us: You are good enough. You should not fixate on your deficits. Look at the one who put his life on the line for you. You are so valuable that someone gave himself up for you, that someone loved you unconditionally.

The images with which the cantata describes this unconditional love are foreign to us today. But it is important to interpret them for us today. There is the image of the blood that Jesus shed for us. We should not think of atonement, as if Jesus had to die for us so that God could forgive us. That is not what is expressed in this image. Rather, the blood is a picture of a love that flows into us. John expressed it in such a way that blood and water flow from the pierced heart of Jesus and permeate the whole world. Blood and water stand for the love that purifies us from everything that clouds our true nature and that fills us with a source of love from which we can always draw and which never runs dry.

So I would like to look at some of the images in the cantata. Firstly, there is the image that the bass sings about in his recitative: we are stained by sin. Yes, our whole spirit is covered, clouded. Sin consists in allowing the original image of God in us to be clouded by false images. In the tenor aria, we sing of the divine source that cleanses us from these clouds. Rudolf Lutz has called this aria a “spiritual washing machine”. That is a beautiful image for what happens to us in this aria. When we hear it, we are purified. A Protestant pastor from the former GDR tells me: every time the Stasi visited him, he tried to stay clear. But after the Stasi left, he always felt the need to go under the shower and wash off the stickiness they had imparted. Pythagoras, the Greek philosopher, attributed this cleansing and healing effect to music. He believes that a person would become ill if the inner vibrations got mixed up, if they stuck together, as it were. Music brings the vibrations into their original order. This is how purification happens when we listen to this aria. We don’t need to believe in redemption. We are washed clean of all self-reproach and self-accusation. We feel pure and redeemed.

We experience in the music what the text wants to tell us as good news. The love of Jesus triumphs over all guilt. That is why we can live full of confidence. We should stop constantly circling around our guilt and sin, judging everything we do. I know many people who think every night: If only I had decided differently, if only I had been more attentive and kind in my conversations with my daughter, with my son, with my friends. In their evaluation of their actions, they are full of doubts as to whether everything was right. And they are not free from their ponderings about their words and deeds. Looking at the blood of Jesus, at his love with which he loved us to perfection on the cross, should free us from these musings. What is past is past. It is over. We can no longer change it. But we may trust that it is extinguished by the divine source of love, that everything that burdens us sinks into the sea of this divine love.

In the recitative, the contralto sings, “Their treasure of souls, their highest good, is Jesus’ priceless blood.” Treasure is an image for our true selves. Many are afraid to look inside themselves. One woman told me, “I can’t go into the silence. There’s a volcano going off inside me.” Jesus told us a parable about the treasure in the field. He means we have to get our hands dirty to dig up the treasure in the field. We have to dig through our emotions like fear and anger, envy and jealousy, greed and resentment, bitterness and discontent to find the treasure in the field. In the cantata, the treasure of the soul is identified with the blood of Christ. It means: When I go through all the chaos of my feelings and passions and come upon my true self, that self is filled with the love of Jesus. At the bottom of my soul I do not find a volcano, but the love of Jesus filling the inner space within me. This is an optimistic image. It gives us the courage to let everything that arises within us be. It is allowed to be. We need not be frightened by what comes up in us when we become still. We should look at it and go deeper into the bottom of our soul. There we meet our soul treasure, the love of Jesus. And where the love of Jesus is in us, guilt has no access. Self-reproaches cannot penetrate there. The love of Jesus forms a shelter in us at the bottom of our soul. There we are protected from the hurtful words of other people, there we are also protected from the temptations to which we are exposed in our everyday life.

The bass aria sings full of confidence and quiet mockery that the whole army of hell has no chance of making us afraid. 38 times the bass sings “Verstumme “. I believe that Bach has in mind here the healing of the paralytic from John 5. John writes of the man who has been sick for 38 years. 38 refers to the exodus of the Israelites from Egypt. The Israelites had already reached their goal after two years. But because they rebelled against God, they had to wander through the desert for another 38 years, “until all the men who were able to bear arms had died”. So the man who is sick for 38 years has no weapons left. He cannot separate himself. The Gospel of John describes how this man feels like a victim. He complains that no one has time for him and that everyone else has it better. Jesus does not address his whining, but confronts him with his own power: “Get up, take up your bed and walk!” Stop complaining. Take your inhibitions, your fears under your arm and go your way. In the music we feel the power that comes from Christ. It is an optimistic music. We are to take our life into our own hands and dare it in God. If we only trust in ourselves, we will not make it in life. But if we have our ground in God, we will dare. The desert fathers in the 4th century speak of the struggle with demons, with passions and emotions. They do not feel like victims. They have a desire to fight this battle. This desire to fight with everything that wants to keep us from living is what we hear in this wonderful bass aria and it communicates itself to us as we listen.

The soprano sings with confidence that the blood of Jesus – his love – will allow us to inherit heaven. Love – the Gospel tells us – is stronger than death. In death we will fall into this love of God forever. Gabriel Marcel, a French philosopher, once said: “To love is to say to another: you, you will not die.” Bach’s music takes away all fear of death. The love that becomes audible in it is stronger than death.

The cantata closes with the chorale “Führ auch mein Herz und Sinn”. When the choir sings together and when the congregation sings together, hearts become one with each other. Salvation is not something purely individual. In singing we also experience community. The Greek word for peace “Eirene” comes from music. Peace arises when all the tones – the light and the dark, the high and the low – sound together in me. When I come into harmony with myself in singing, then I can also sound together with people, then community arises, then peace arises. And in singing together we come into contact with the joy that unites us all.

Listening to this wonderful music together leads, in the words of Heidegger, to a sense of security. And we feel one with each other. Martin Walser once said: “If you find something beautiful, you are never alone. When you find something beautiful, you are redeemed, redeemed from yourself.” That is what I wish for everyone who is now listening to this cantata again, that the music connects us with each other in the deepest way, so that the beauty of this music conveys to us that we are never alone. And that the music redeems us from circling around ourselves. By hearing the sacred words, we feel we belong. We hear the inaudible, the miraculous of the message of Jesus Christ that connects us all in the depths of our souls in a love that is stronger than death.

This text has been translated with DeepL (www.deepl.com).