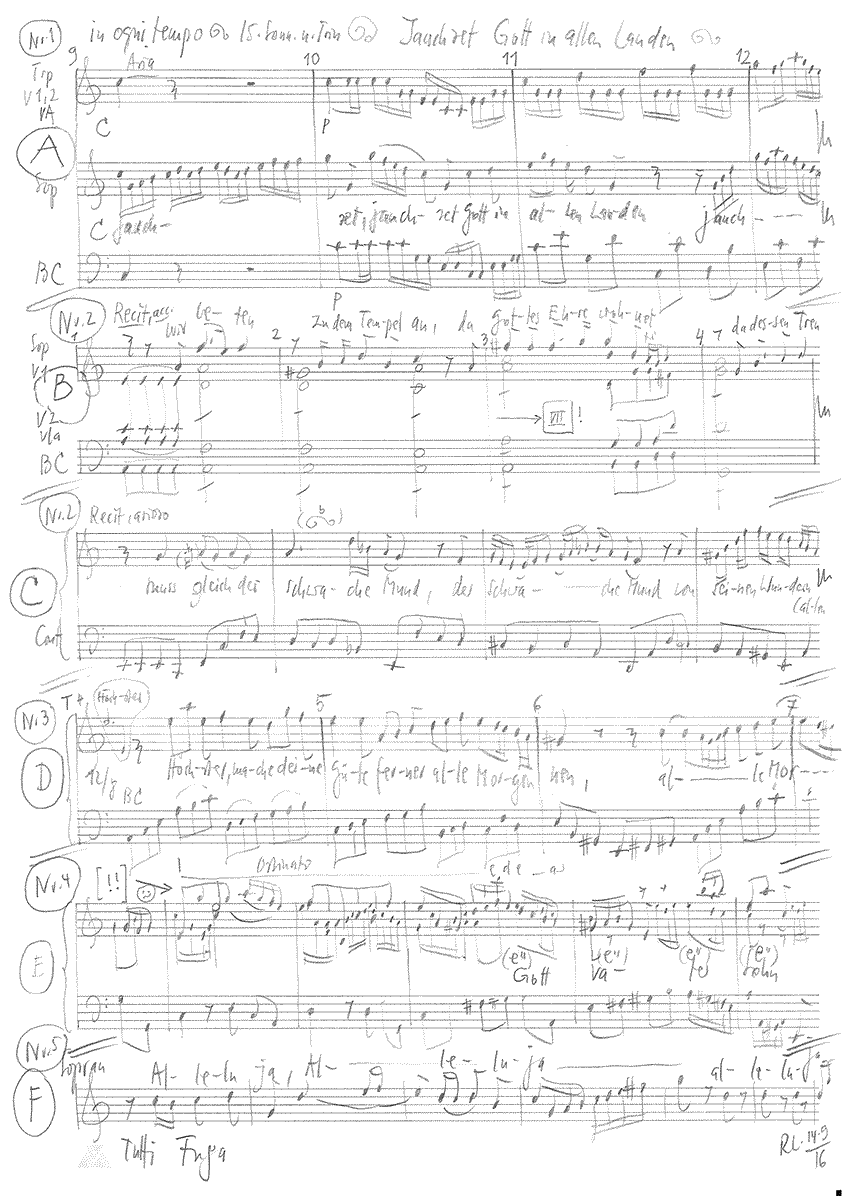

Jauchzet Gott in allen Landen

BWV 051 // For the Fifteenth Sunday after Trinity

(Praise ye God in ev’ry nation) for soprano, trumpet, strings and basso continuo

Would you like to enjoy our videos ad-free? Subscribe to YouTube Premium now...

Workshop

Reflective lecture

Soloists

Soprano

Sibylla Rubens

Orchestra

Conductor & cembalo

Rudolf Lutz

Violin

Renate Steinmann, Monika Baer

Viola

Susanna Hefti

Violoncello

Martin Zeller

Violone

Markus Bernhard

Bassoon

Susann Landert

Tromba da tirarsi

Patrick Henrichs

Organ

Nicola Cumer

Musical director & conductor

Rudolf Lutz

Workshop

Participants

Karl Graf, Rudolf Lutz

Reflective lecture

Speaker

Adolf Muschg

Recording & editing

Recording date

15.09.2016

Recording location

Trogen AR (Schweiz) // Evangelische Kirche

Sound engineer

Stefan Ritzenthaler

Director

Meinrad Keel

Production manager

Johannes Widmer

Production

GALLUS MEDIA AG, Switzerland

Producer

J.S. Bach Foundation of St. Gallen, Switzerland

Librettist

Text

Unknown,

4th movement, substitute verse to hymn by Johann Gramann, 1548

First performance

15th Sunday after Trinity,

17 September 1730

In-depth analysis

“Jauchzet Gott in allen Landen” (Praise ye God in ev’ry nation, BWV 51) is something of a solitaire in Bach’s sacred oeuvre. With its combination of solo soprano and trumpet, the work is a veritable “cantata” in the Italian sense of the word, and it is even – unusually so – designated as such on Bach’s autograph score. The cantata was probably written for the Fifteenth Sunday after Trinity in 1730, although, as can be inferred from the title page, Bach also assigned the work the flexible use “in ogni Tempo” (for any occasion), a designation that well suits the work’s versatile nature as music of praise and thanksgiving. With the exception of the choralebased movement no. 4, the cantata is possibly a revival of an older work; later, in Halle, Bach’s son Wilhelm Friedemann composed a new version with two trumpets and timpani in the outer movements.

The music of the opening aria emerges from the unison introduction, whose fanfare motives are transformed by the soprano into a bravura cantilena replete with tirata figures. In this setting, a liberated miniature arises from the buoyant music for violin I, trumpet, solo soprano and string orchestra. Then, in a style characteristic of Bach, the gentler middle section works consistently with the broken chords of the opening section, ere an elegant transitional phrase to the recapitulation lends the movement elements of a throughcomposed style.

The following recitative, by contrast, is marked by a stark shift in affect. Accompanied by an enigmatic string setting with long, undulating phrases, the solo voice, in line with the text, embarks on a humble path to church (“In prayer we now thy temple face”), although this procession, for the enthralled listener, transitions all too quickly into a flowing andante section. The “feeble voice” of the earthly thanksgiving is strikingly portrayed by the sighing and stammering vocalist, who, together with the continuo, fails in all efforts at ornamentation: here, the faithful face God in all their weakness, yet still may hope that the Almighty looks with favour on their necessarily “modest praise”.

The second aria, in a pastoral 12/8 metre, is an intimate prayer whose gentle three-quaver pattern provides for an ostinato-like pulse. The floating transparency of the exposed vocal part demands the highest degree of flexibility and expressive tension from the singer; the key to the movement’s character is perhaps the “grateful spirit” highlighted in the middle section, which allows the aria, presented as if with the shining eyes of a child, to represent a life blessed with protection and care.

In the ensuing chorale setting, this highly subjective mood gives way to a more collective approach in which the presentation of a chorale melody is enveloped by an industrious trio of two violins and a lively bass. While the text of “Now laud and praise with honour, God Father, Son, and Holy Ghost” functions as an affirmation of the Trinity, the intricate imitation in the instrumental parts stands for the triumph of creating music to please God as well as the travails of a life of piety. The chorale text is relatively long – twelve lines – but the swinging triple metre ensures that the setting never descends into turgid counterpoint; moreover, Bach shapes the transition to the closing Alleluja as a captivating surprise. In this grand finale, the nigh-forgotten trumpet makes a victorious re-entry, while the string ensemble, by echoing the dense style of the chorale in accompanying passages and interludes, prevents the swift, 2/4 - metre music from becoming all too breathless. In this movement, the solo voice alternates lower passages with lines that soar to lofty peaks: in bar 180, the soprano even ascends to the rare C3, before, in a flurry of cascading lines, succinctly closing one of the most dazzling vocal compositions Bach ever wrote. The Thomascantor, rarely spoiled by the quality of his ensemble, must, in September of 1730, have had an exceptional descant singer at his disposal – the way he made the most of this rare opportunity enchants us to this day.

Libretto

1. Arie

Jauchzet Gott in allen Landen!

Was der Himmel und die Welt

an Geschöpfen in sich hält,

müssen dessen Ruhm erhöhen,

und wir wollen unserm Gott

gleichfalls itzt ein Opfer bringen,

daß er uns in Kreuz und Not

allezeit hat beigestanden.

2. Rezitativ

Wir beten zu dem Tempel an,

da Gottes Ehre wohnet;

da dessen Treu,

so täglich neu,

mit lauter Segen lohnet.

Wir preisen, was er an uns hat getan.

Muß gleich der schwache Mund

von seinen Wundern lallen,

so kann ein schlechtes Lob ihm dennoch

wohlgefallen.

3. Arie

Höchster, mache deine Güte

ferner alle Morgen neu.

So soll vor die Vatertreu

auch ein dankbares Gemüte

durch ein frommes Leben weisen,

daß wir deine Kinder heißen.

4. Choral

Sei Lob und Preis mit Ehren

Gott Vater, Sohn, Heiligem Geist!

Der woll in uns vermehren,

was er uns aus Gnaden verheißt,

daß wir ihm fest vertrauen,

gänzlich uns lassn auf ihn,

von Herzen auf ihn bauen,

daß unsr Herz, Mut und Sinn

ihm festiglich anhangen;

drauf singen wir zur Stund:

Amen! Wir werdns erlangen,

glaubn wir zu aller Stund.

Alleluja!

Adolf Muschg

The praise of God as a lament

When we listen to the cantata “Jauchzet Gott in allen Landen” (Rejoice God in all lands), it can happen to us that for once we hear this lament almost self-indulgently. Then we can recognise in it the birthmark of creation threatened with us and by us.

“And we will also now

a sacrifice to our God,

that in cross and adversity

has always stood by us.”

Was Johann Sebastian Bach a devout Christian?

The question makes about as much sense as asking whether a doctor believes in medicine, or – and perhaps more appropriately – asking an employee whether he thinks the company that gives him bread is necessary. For Bach’s contemporaries, the question of their Christianity was already made superfluous by the fact that it was obligatory for bourgeois existence, even if the denomination differed. But since the Peace of Westphalia, Europe was beyond bloody religious wars, even if there was now a lot of arguing about God, the world and nature, but mainly on paper. The fact that free spirits like Voltaire declared war on the church as such remained the brilliant exception; at most – for the increased piety of the Pietists – the “wall church” was up for discussion.

But Bach’s evangelical Christianity remained untouched by such refinements – what he claimed for himself was Luther’s double freedom, which reads: “A Christian man is a free lord over all things and subject to no one”, but also: “A Christian man is a servant of all things and subject to everyone”. We admire Bach for the way he translated this faithful double meaning into an art in which the freedom with which a theme is treated is at the same time followed by a strict binding of the tones, where the arbitrary no longer has any place. But the following was undoubtedly true of Bach as a man: baptised is baptised, his activity, whether for the church or outside it, no longer demanded any extra profession of faith from him, the ritual with which the architecture of church and world was saturated was sufficient. For his contemporaries, Bach’s music was naturally, and by no means conspicuously, part of this common event of faith, in which an approved rhetoric set the framework and tone of piety. The composer took up this keynote and varied it according to the occasion. And even in the courtly or urban bourgeois milieu, at the Reformed court of Köthen or the Catholic court of Dresden, his professional self-image and his development as an artist were based on a praise of God that knows no bounds and in which one can never be master enough. What touches us as a case of genius is thus the product of a connection that has been lost to us today – to most, and certainly to society as a whole. Even if the church space, as here in Trogen, remains wonderful as a concert space: it is no longer compelling.

So the question of who is still a believing Christian here is really addressed to us. It is the question of what it means when we listen to a Bach cantata like this BWV 51 with feelings that its first listeners certainly did not share – and for which the composer would also have lacked the imagination.

“That we may firmly trust him,

“that we may trust in him completely,

“and build on him with all our hearts,

that our heart, courage and mind

firmly cling to him” –

around 1730, on the 15th Sunday after Trinity, i.e. the first Sunday in September, the congregation of St Thomas’ Church heard the sung reverberation of the sermon in this text, in a form that was consumed with more pleasure, for fortunately Luther’s Reformation had not driven all art out of the service and had also handled the ban on images more leniently than Zwingli and Calvin. But it was self-evident that the arts had to remain subservient to the Word, even in St Thomas’ Church in Leipzig; they remained ornaments, justified by the idea that a worthy garment also belongs to a sacramental content. But a mediocre sermon changed the substantial hierarchy as little as gifted music.

To put it bluntly: even the text of a cantata can be as wooden as that of the cantata “Jauchzet Gott in allen Landen” – the music is created for it to be heard, and also creates the miracle that it can be heard. And in our ears it now ensures that we can confidently overhear him. He merges into Bach like salt in soup, and we are spared the question of how it would taste to us, taken by itself. We do not hear God’s word, we hear Bach – and there is no question that we have heard him not only technically better, but also musically more beautiful than the cantata was ever heard by his contemporaries – or by himself. Today’s concert audiences are not satisfied with less, whereas for the Thomas congregation of around 1730, human imperfection would have been included in the praise of God even in this form. It enjoyed the beautiful relief of the tones, while our enjoyment of the cantata has become more sophisticated since we also first appreciate its sacred dimension aesthetically. We are gripped by the structure of this music, whose dignity is even greater than its grace, which is why we have become accustomed to calling it “objective” or even “absolute”. What only a few connoisseurs heard back then – the rank of this music – is now for everyone part of the fama that precedes it and the aura that surrounds it.

It must also be said that Bach appears to us as unprecedented, as a solitaire, because the sacred and social environment of his music has broken away so completely. We believe we can make sense of Mozart’s music even more easily, even if we take the costumes for it from Der Rosenkavalier. They provide just enough material for our imagination of a special subject, that is: a genius in the sense of the late 18th and especially the 19th century – from child prodigy to early death, from frivolity to profligacy – to make the sublime serenity of his music doubly mysterious. Since then, the reception of art has also demanded a fitting, i.e.: unconventional, preferably tragic life-legend of its creator, which we hear again in his music, and with good reason too: for it sounds to us from it seemingly 1:1, from the lonely Winter Traveller to the Twilight of the Gods.

None of this is the case with Bach; his many-headed musical household, including the communal living with his pupils, is, right down to the dressing gown and wig, of a pervasive conventionality that can hardly be lightened by a few anecdotes. We see a bourgeois music master at work, going for bread and looking, not without cuteness, for the next job that also promises him the butter to go with it. This professional mobility is, in a sense, the most conspicuous movement we perceive in him before he is settled in Leipzig, right up to his utterly untragic end. Such a life does not lend itself to an artist’s narrative – whereas his great contemporary Handel certainly had one to offer and allowed himself to simply look past the little Bach. Certainly, this Bach has an inner biography of subtle reception of Telemann, Vivaldi and Lully to offer music connoisseurs; this may have been a full evening for him. It is not enough for our understanding – or reverent lack of understanding – of his greatness. It remains oriented towards the case of genius, which in the highly gifted Bach family, to a certain extent, only became more manifest in his sons. Our veneration of the unparalleled Bach is based on the paradox that it could only be awakened quasi-contrapuntally by the triumph of the genius subject – this began with Mendelssohn. And the veneration only grew immeasurably when the cultural supports of the subject also began to fall and its cult became more and more incomplete and questionable, until the de facto abdication of the person in the collectives of the 20th century and of the indivisible individual through psychoanalysis.

These shocks and overthrows of the conventional image of the human being had the curious side effect of making Bach Licht shine ever stronger and more unchallenged. For modernism and postmodernism, it became the epitome – precisely: of absolute, objective art. Which it had also been for its creator – but as a humble reflection of the objective omnipotence of an absolute greatness. “If the weak mouth must slur his wonders, / A bad praise can still please him.”

Since no time can exist God-free, globalised society also has its God: the market. Its gospel is competition, its promise the survival of the fittest, its soul its own advantage. So let us praise God for giving us a great Bach evening under these conditions, with brilliant performers, for the benefit of an audience – also, no doubt, for the benefit of Bach’s music. As their grateful customers, we can listen to the coloratura of his Hosianna in the 5th movement without any obligation to believe what we hear, and I, too, must use the superlative of the market in praise of his music: incomparable. But on the 15th Sunday after Trinity, of all days, at the beginning of the harvest season, i.e. the agricultural boom, the church calendar demanded a sermon against clinging to earthly goods. One is not a spoilsport if one remembers that we enjoy the 51st cantata quite outside the context in which it was composed and without which it would not have come into being, and thus could not be enjoyed. It is already a great deal if we succeed in sealing off its resonant space from the obligatory noise of the market: we hear a very different voice from that of the cheap Jacob. We owe this opportunity to the experience of an art removed from its context as an absolute – it is precisely its distance that, when it encounters us in non-objective objectivity, creates the greatest closeness, as if in it wanderlust and homesickness had become one.

Yes: Bach’s music has the strange quality of not drowning out the emptiness in which we hear it, not disguising it, not glossing over it, but making it palpable. It turns us music customers into eavesdroppers. We listen to a thing that cannot be had on any market because it cannot be had at all: one would have to be it, and then one would no longer be a “man”, not a statistical quantity, but a human being in all due smallness – and even grateful for it. The beautiful is nothing but the beginning of the terrible, says a Rilke elegy, and we admire it so because it calmly disdains to destroy us. Something of this dreadful beauty touches us in Bach’s cantatas, which have only one thing to tell us about the sacred, but this is unmistakable: It is missing, and we are missing it; under the impression of this overwhelming absence, we, in Bach, almost become something like a congregation again.

Then we are able to hear the praise of God in this cantata no. 51 as a lament. But in doing so, we are not just lamenting ourselves, nor are we lamenting an absent God. Rather, it can happen to us with Bach that for once we hear this lament almost self-less and recognise it as the birthmark of creation, which is threatened with us and by us. If we are left with any consolation, only art can offer it. I draw it once again – at the end of this reflection – from Rilke’s First Duino Elegy, which is about dealing with the dead. And I would like to take the liberty of assuming that this way of dealing with the dead has always been, and still is, the true source of art; that is, the way we deal with our mortality. And with that, I suppose, we come again – thanks to its stellar distance – into the vicinity of Bach’s music.

“But we who need such great

secrets, from which sorrow so often springs

blessed progress springs from sorrow – could we be without them?

Is the legend in vain that once in the lament for Lino’s

that once, in the lament for Linos, daring first music penetrated arid torpor;

that only in the frightened space from which a nearly divine youth

suddenly left for ever, the emptiness entered into that vibration

vibration that now sweeps us away and comforts and helps us”.

This text has been translated with DeepL (www.deepl.com).