Wer mich liebet, der wird mein Wort halten

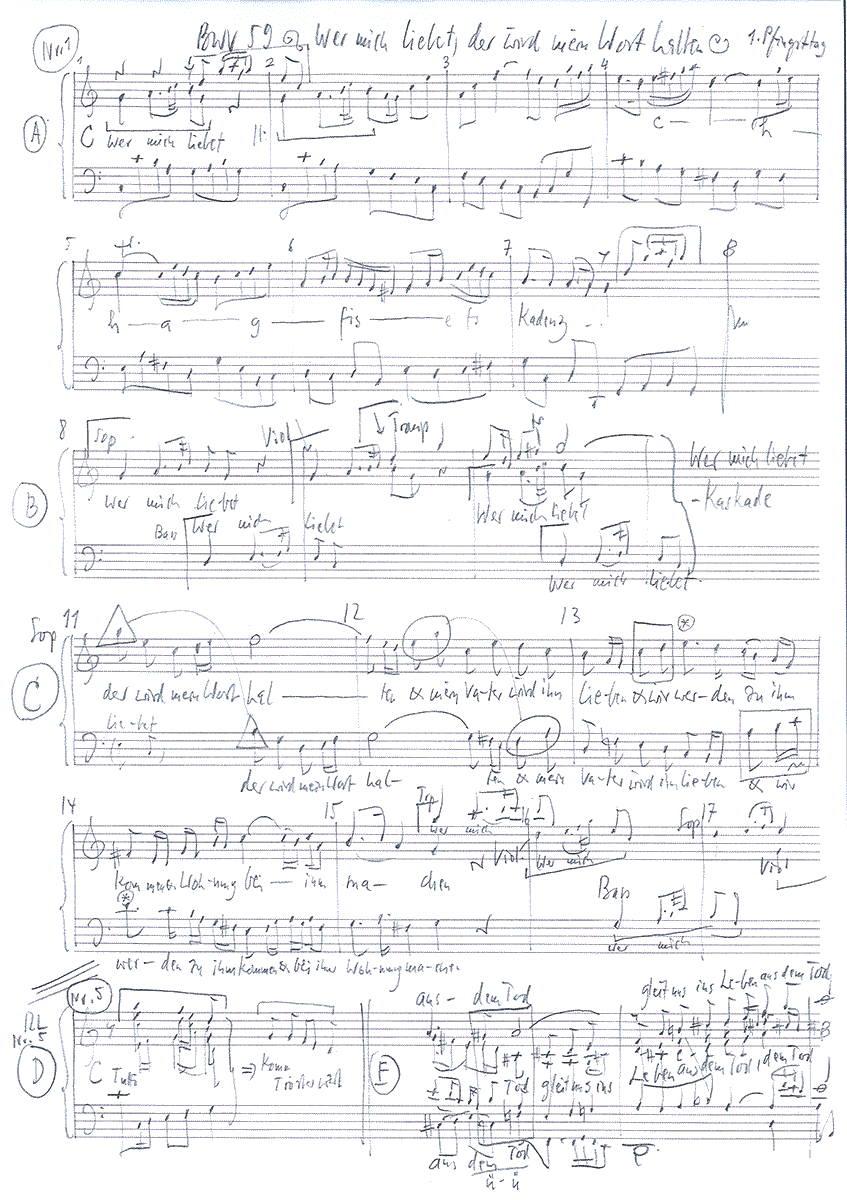

BWV 059 // For Pentecost (Whitsunday)

(He who loves me will keep my commandments) for soprano, bass and four-part vocal ensemble, trumpet I+II, timpani, bassoon, strings and continuo

Would you like to enjoy our videos ad-free? Subscribe to YouTube Premium now...

Workshop

Reflective lecture

Orchestra

Conductor & cembalo

Rudolf Lutz

Violin

Plamena Nikitassova, Renate Steinmann

Viola

Susanna Hefti

Violoncello

Martin Zeller

Violone

Iris Finkbeiner

Bassoon

Susann Landert

Tromba da tirarsi

Patrick Henrichs, Peter Hasel

Timpani

Martin Homann

Organ

Norbert Zeilberger

Musical director & conductor

Rudolf Lutz

Workshop

Participants

Karl Graf, Rudolf Lutz

Reflective lecture

Speaker

Verena Kast

Recording & editing

Recording date

05/25/2012

Recording location

Trogen

Sound engineer

Stefan Ritzenthaler

Director

Meinrad Keel

Production manager

Johannes Widmer

Production

GALLUS MEDIA AG, Switzerland

Composer of chorale No. 5

Rudolf Lutz

Producer

J.S. Bach Foundation of St. Gallen, Switzerland

Librettist

Text No. 1

Quote from John 14:23

Text No. 2, 4

Erdmann Neumeister (1671–1756)

Text No. 3, 5

Martin Luther (1483–1546)

First performance

First Day of Pentecost,

28 May 1724

In-depth analysis

Bach composed BWV 59 to a libretto written by renowned text-reformer Erdmann Neumeister that was first printed in 1714 in Eisenach, then reprinted in 1716 in Leipzig; it appears that Bach set only four of the seven verses to music, and the extant version of the cantata ends with a bass aria with solo violin. This unusual ordering of movements places the chorale in the middle of the work, a situation that was quietly “corrected” in 19th-century publications of the work with the aim of establishing a conventionally well-formed conclusion. Because Bach substantially reworked and extended the introductory movement for reuse in BWV 74, and because the composition’s date (1723 and / or1724) as well as the occasion (probably a university church service) remain unverified, the cantata often suffers the ill repute attached to an incomplete and makeshift composition – a shadow that should be lifted from this charming work.

The work’s exquisite sound is established from the very outset through the soft and amiable Pentecostal tone of the introductory movement. The warm, flowing string setting is complemented by a cantabile pair of trumpets and discreet timpani; the resonant soprano and bass voices integrate seamlessly into the ensemble, forming a perfect whole. Opening with an expressive head motive, the various elements of the movement interweave in flowing phrases. With this simple yet artful concept, the music is eminiscent of the charming tone of earlier sacred concerti, for instance those by Johann Schelle, one of Bach’s predecessors as Thomaskantor. Elements of Bach’s Weimar style are clearly audible in the composition, which has led to the – uncorroborated – conjecture that at least some of the movements stem from an earlier composition.

The soprano recitative “Oh, what are then these honours”, accompanied by a dark-timbred string setting, describes in celebratory tones the moment in which Jesus, through his presence, raises mankind from the dust. Here, Neumeister’s masterful formal diction and distinctive dramatic metaphors seem to have inspired Bach to a particularly vivid setting, which he concluded with an arioso passage giving an enraptured description of how beautiful it would be if we mortals shared in God’s wonderous love.

This is followed by a chorale movement that employs the Lutheran hymn “Come, Holy Spirit” to refer to the events of Pentecost. While the first violins support the soprano voice, the second violins and the viola – a favourite instrument of Bach’s – enjoy independent lines within the four-part structure.

Although the aria “The world with all its realms and kingdoms” opens with words on the transience of all earthly life, here, too, the music is replete with dulcet tones that call to mind the most beautiful movements from Bach’s accompanied violin sonatas. In this musical vision of love fulfilled, the bass soloist proffers a sonorous declaration: those who hold God in their hearts are not only blessed in spirit but may venture a glimpse into the majesty of heaven. Here, Bach’s simple musical phrases and concise, expressive figures embody both the clarity of the Pentecostal light and the childlike simplicity of the faithful soul.

It cannot be ruled out that the marking of “Corale segue” at the end of the original bass part is not a reference to a subsequent hymn setting, nor are the various theories on why Bach never set the remaining verses of Neumeister’s libretto entirely convincing. This ambiguous situation inspired Rudolf Lutz to compose a new setting to the chorale “Gott, Heilger Geist, du Tröster wert”, which followed in the original libretto. Based on a rich array of baroque idioms and techniques, the composition rounds out the cantata with the same pragmatic spirit that would have been adopted in Bach’s day, had a colleague prepared a re-performance of the work. The figural setting takes up the elegant lines of the trumpets and timpani from the opening movement and treats the chorale in a motetlike and distinctly cantabile style that not only harks back to the ethereal aria but also uses the full instrumentation to great effect. In this setting, the buoyant head-motive of “God, Holy Spirit” and the syncopated response from the winds form the source of inspiration for the whole movement.

Libretto

1. Arie (Duett Sopran, Bass)

«Wer mich liebet, der wird mein Wort halten,

und mein Vater wird ihn lieben, und wir werden

zu ihm kommen und Wohnung bei ihm machen.»

2. Rezitativ (Sopran)

O, was sind das vor Ehren,

worzu uns Jesus setzt?

Der uns so würdig schätzt,

daß er verheißt,

samt Vater und dem heilgen Geist

in unsern Herzen einzukehren.

O, was sind das vor Ehren?

Der Mensch ist Staub,

der Eitelkeit ihr Raub,

der Müh und Arbeit Trauerspiel

und alles Elends Zweck und Ziel.

Wie nun? Der Allerhöchste spricht,

er will in unsern Seelen

die Wohnung sich erwählen.

Ach, was tut Gottes Liebe nicht?

Ach, daß doch, wie er wollte,

ihn auch ein jeder lieben sollte.

3. Choral

Komm, Heiliger Geist, Herre Gott,

erfüll mit deiner Gnaden Gut

deiner Gläubigen Herz, Mut und Sinn.

Dein brünstig Lieb entzünd in ihn‘n.

O Herr, durch deines Lichtes Glanz

zu dem Glauben versammlet hast

das Volk aus aller Welt Zungen;

das sei dir, Herr, zu Lob gesungen.

Alleluja, Alleluja.

4. Arie (Bass)

Die Welt mit allen Königreichen,

die Welt mit aller Herrlichkeit,

kann dieser Herrlichkeit nicht gleichen,

womit uns unser Gott erfreut:

daß er in unsern Herzen thronet

und wie in einem Himmel wohnet.

Ach! ach Gott, wie selig sind wir doch,

wie selig werden wir erst noch,

wenn wir nach dieser Zeit der Erden

bei dir im Himmel wohnen werden.

5. Choral

Gott, Heiliger Geist, du Tröster wert,

gib dein’m Volk einerlei Sinn auf Erd,

steh bei uns in der letzten Not!

G’leit uns ins Leben aus dem Tod!

Verena Kast

“Engaging with uplifted emotions”.

Biblical texts, such as the miracle of Pentecost, are also primal stories which, if one leaves aside the context of faith, concern important anthropological basic human needs. The text of the cantata “Whoever loves me will keep my word” resonates with a promise, an invitation to anticipation. One can look forward to something that can fundamentally change one’s life.

First, however, two worlds confront each other. In the recitative, the transience of man is named: man made of dust, human life a tragedy, full of toil and labour – and yet the promise: God “will choose a dwelling place in our souls” – and that is the reason for the anticipation.

What could this mean? It is promised that the Holy Spirit will enliven the heart, courage and mind of people and ignite a burning love in them. The promise is the enlivened heart, the Spirit-filled heart, the inspired heart, a living heart.

The heart was seen by Aristotle as the seat of the soul, the centre of the soul. From the heart, according to this view, the soul controlled the body. A central organ, then – and as such we still experience it today – not only in symbolism, but also physically.

Symbolically, the heart is considered the centre of love, bonding and attachment. We are devoted to each other from the heart, sometimes one heart and one soul. If we lose love, our hearts sometimes break. You can give your heart away, take it by storm. But there is also a sluggishness of heart, or even a cold heart – and that is lifeless, almost as if dead. Connected to the heart are the feelings: joy, interest – so we are wholeheartedly attached to something, but also sadness, pain, fear, then transferred to courage, kindness and despair. If the feelings are mentioned in connection with the heart, then they are violent – it is about passion or about its paralysis, the numbness, and it is central and important for our life.

Feelings interact with other people and with the world. If we experience something beautiful and good, we rejoice with all our heart, especially if we can share it with others. If we experience malice, suffering, we are deeply affected in our heart – and this can certainly lead to physical heart problems.

The experience of uplifted feeling

But the promise in this cantata now is that the uplifted emotions will be activated: Courage, meaning, burning love. It is not about hurt in this text – it is about elation and the associated experience of meaning that balances or even overcomes the feelings of being hurt. In the concluding chorale, in a slightly altered version of the text (Gardiner), it says: “Thou holy heat, sweet consolation, now help us joyfully and confidently (…) and strengthen the flesh’s stupidity”. The meaning of “stupidity” has changed somewhat over time. Originally, stupidity meant physical frailty, weakness, but also timidity. This promised revival of the heart is thus meant to comfort people, to strengthen their confidence in life so that they can live confidently, even though life always knows death, and life is often also arduous.

It is about the experience of uplifted feelings that is promised here: about joy, inspiration, hope. Joy is the basis of it. The possibility of being able to experience elevated feelings is part of the basic human make-up, these feelings, like all emotions and feelings, are biologically anchored; in the course of life we have various experiences with these feelings, with the expression of these feelings, and they become the emotional colouring of our personality. (Fearful people, gruff people, more cheerful people, etc.) In the context of joy, we can describe a biography of our joys. As children we have certain joys that we express without restraint; what triggers joy changes to some extent in the course of life. For example, we can easily remember the joys we experienced on a beautiful summer day. But we can also ask ourselves what triggers joy today. At the moment, certainly listening to music. And there are many joys in between. For each age, we can ask ourselves what made us happy then, but we can also ask ourselves what we look forward to in the future. What changes in the course of life is above all the expression of feelings: as adults we control our feelings more. Can we reconcile the expression of a wild joy with our self-image, can we still jump for joy?

What does joy do?

Every emotion, and every perceived emotion, every feeling, has a meaning and an effect. When we rejoice, we experience life as better than expected, it is more beautiful than could have been foreseen. Physically we experience ourselves as invigorated, energised, we want to jump, dance, sing. We feel in harmony with ourselves, with others, with the world: we are alive, have a good sense of self-worth without having to worry about it – are therefore also more generous than normal, we are more solidary, more loving. We also feel secure, in ourselves, in the world. We have more trust in life – less fear. We look at ourselves and others with friendlier eyes – not with grumbling, criticising or even bitter eyes. To be able to remember joy again and again, we have to perceive it when it happens. Then we can revive it again and again in our memory. Joy can only unfold its great effect if we take time for it. But then it can always be recalled in memory and we can also share it with others through storytelling. Joy becomes more when we share it with others. This updating of old joys is an important resource also for old age. There are many things that trigger joy. One trigger of joy is to create something together with other people, to build something up, to invent something together. We infect each other with joy – and so, at least in the first phase (later, unfortunately, comes competitive thinking), it is possible for us to approach something together with inspiration, to be creative with each other. Joy is the basis for inspiration – being caught by the spirit, being enthusiastic.

The idea of the Pentecost story

When we are joyful, when we are even inspired – and that is a mixture of joy, interest, trust and confidence – then we can also have a vision of what we want to create together. The idea in the Pentecost story that people can gather together and speak to each other in all tongues is ultimately based on the basic feeling of joy and increased joy, enthusiasm. Enthusiasm, inspiration can be understood as being gripped, affected by thoughts, insights, feelings that seem to be beyond reason or out of reason. In creativity research, inspiration is often seen as the influence of divine activity. (Arthur Koestler, Der göttliche Funke, Der schöpferische Akt in Kunst und Wissenschaft, Scherz, Bern/München/Vienna 1966). Even sober people speak of something suddenly taking possession of them that goes beyond them. Today, this is described as the experience of emergence: a change that cannot be explained logically, that opens up a new perspective and is accompanied by an uplifted attitude to life: one is enthusiastic, elated. In times when one was less sober, one spoke of ecstasy. In ecstasy, man steps out of himself and makes room for a God who then speaks from him. More soberly: one is gripped by an idea that formulates itself, that takes space for itself – and this corresponds quite well with the Pentecost story: “And they were all filled with the Holy Spirit, and began to speak with other tongues, as the Spirit gave them utterance (…)”. And out of this experience came a sense of “we”, a vision, the vision of the early Christian community. We all know that visions are translated into reality as far as possible, but then they solidify and become incrusted. And then we need new inspiration for something new. Freshly engaging with joy again, expecting it – trusting that it is always there. And it doesn’t start with the big emotions, but with quiet joy, but above all with shared joy.

Anticipation as a risk

So the cantata text invites us to allow for these emotional experiences. For the time being, however, it is only anticipation. For many, anticipation is a risky joy: in anticipation, we imagine something that will fill us with great joy. If the expected does not come true, we can be disappointed. So it is better not to allow anticipation in order not to be disappointed? It would be better to think differently. If we manage to keep ourselves so open that we don’t have to hold on to our expectations, we can also let go of them, then we can allow and enjoy anticipation. Anticipation is the best joy. Whatever happens, no one can take the anticipation away from us. We have already enjoyed it. Neuroscientists, by the way, have shown that anticipation is associated with some fear, or anxiety, and is therefore particularly exciting. And that our reward system in the brain, which kicks in when we feel good, is particularly activated during anticipation. Material things that make us feel good become weaker and weaker in their effect over time, stimulate our reward system less and less. Not so anticipation and also joy. This intrinsic reward gives us the most good feelings. (Gerhard Roth)

Now, however, the recitative ends with the sigh, “Ah, that yet, as he would, / Each one should love him too.” A condition, a demand, an invitation? Psychologically, we don’t need this condition. Joy, inspiration, anticipation – all emotions – they are accessible to man, however, it is necessary to perceive these exalted emotions and also to value them.

Becoming alive

I would understand this commandment of love in this way: If we rejoice, then we can also engage with others, we can love others and life, we become alive, inspired occasionally, carried by hope for the better despite all adversity, are always on the way from death to life, become alive.

I would like to conclude by returning to the stupidity of the flesh, to our frailty weakness, timidity. In psychosomatic medicine today, many disorders are understood as the result of distress, of harmful stress phenomena. And these are not only seen in a current excessive demand, but in the context of a person’s whole biography. In order to counteract the consequences of stress, in order to de-stress, many different methods are named today. Among them, as a very important aspect, is allowing anticipation, consciously experiencing joy, remembering and recounting joyful situations, which enables us to experience these feelings again. Joy and anticipation are often connected with bonds to people, to animals, to nature, to art, and last but not least: music that we like has been proven to de-stress us, to increase our immune defence, but more so when we do it ourselves than when we listen to it alone.

Literature

– Verena Kast, What really counts is the life lived. The Power of Life Review, Kreuz, Freiburg 2010

This text has been translated with DeepL (www.deepl.com).