Lobe den Herrn, meine Seele

BWV 69 // For the Council Election

(Praise thou the Lord, O my spirit) for soprano, alto, tenor and bass, vocal ensemble, trumpet I-III, timpani, oboe I-III, oboe d’amore, strings and basso continuo

Place of composition in the church year

Pericopes for Sunday

Pericopes are the biblical readings for each Sunday and feast day of the liturgical year, for which J. S. Bach composed cantatas. More information on pericopes. Further information on lectionaries.

Would you like to enjoy our videos ad-free? Subscribe to YouTube Premium now...

Workshop

Reflective lecture

Choir

Soprano

Cornelia Fahrion, Gabriela Glaus, Jessica Jans, Susanne Seitter, Ulla Westvik

Alto

Antonia Frey, Laura Kull, Lea Scherer, Jan Thomer, Lisa Weiss

Tenor

Manuel Gerber, Klemens Mölkner, Joël Morand, Nicolas Savoy

Bass

Serafin Heusser, Israel Martins, Philippe Rayot, Julian Redlin, Jean-Christophe Groffe

Orchestra

Conductor

Rudolf Lutz

Violin

Éva Borhi, Péter Barczi, Dorothee Mühleisen, Ildikó Sajgó, Lenka Torgersen, Aliza Vicente

Viola

Sonoko Asabuki, Alberico Giussani, Matthias Jäggi

Violoncello

Maya Amrein, Jakob Valentin Herzog

Violone

Markus Bernhard

Oboe

Andreas Helm, Philipp Wagner, Katharina Arfken

Bassoon

Susann Landert

Trumpet

Patrick Henrichs, Peter Hasel, Klaus Pfeiffer

Timpani

Inez Ellmann

Harpsichord

Thomas Leininger

Organ

Nicola Cumer

Musical director & conductor

Rudolf Lutz

Workshop

Participants

Rudolf Lutz, Pfr. Niklaus Peter

Reflective lecture

Speaker

Philipp Hübl

Recording & editing

Recording date

04/07/2025

Recording location

St. Gallen // Church of St. Laurenzen

Sound engineer

Stefan Ritzenthaler

Producer

Meinrad Keel

Executive producer

Johannes Widmer

Production

GALLUS MEDIA AG, Schweiz

Producer

J.S. Bach-Stiftung, St. Gallen, Schweiz

Librettist

First performance

26 August 1748

Text

Poet unknown

Movement 1: Psalm 103:2; movement 6: “Es woll uns Gott genädig sein” (Martin Luther, 1524), verse 3

Libretto

1. Chor

«Lobe den Herrn, meine Seele, und vergiß nicht, was er dir Gutes getan hat.»

2. Rezitativ – Sopran

Wie groß ist Gottes Güte doch!

Er bracht uns an das Licht, und er erhält uns noch!

Wo findet man nur eine Kreatur, der es an Unterhalt gebricht?

Betrachte doch, mein Geist, der Allmacht unverdeckte Spur,

die auch im Kleinen sich recht groß erweist.

Ach! möcht es mir, o Höchster, doch gelingen,

ein würdig Danklied dir zu bringen!

Doch, sollt es mir hierbei an Kräften fehlen,

so will ich doch, Herr, deinen Ruhm erzählen.

3. Arie – Alt

Meine Seele, auf! erzähle,

was dir Gott erwiesen hat.

Rühme seine Wundertat,

laß, dem Höchsten zu gefallen,

ihm ein frohes Danklied schallen.

4. Rezitativ – Tenor

Der Herr hat große Ding an uns getan;

denn er versorget und erhält,

beschützet und regiert die Welt;

er tut mehr, als man sagen kann.

Jedoch, nur eines zu gedenken:

Was könnt uns Gott wohl bessers schenken,

als daß er unsrer Obrigkeit

den Geist der Weisheit gibet,

die denn zu jeder Zeit

das Böse straft, das Gute liebet?

Ja, der bei Tag und Nacht

vor unsre Wohlfahrt wacht.

Laßt uns dafür den Höchsten preisen;

auf, ruft ihn an, daß er sich auch noch fernerhin

so gnädig woll’ erweisen.

Was unserm Lande schaden kann,

wirst du, o Höchster, von uns wenden

und uns erwünschte Hülfe senden.

Ja, ja, du wirst in Kreuz und Nöten

uns züchtigen, jedoch nicht töten.

5. Arie – Bass

Mein Erlöser und Erhalter,

nimm mich stets in Hut und Wacht!

Steh mir bei in Kreuz und Leiden,

alsdenn singt mein Mund mit Freuden,

Gott hat alles wohl gemacht.

6. Choral

Es danke, Gott, und lobe dich

das Volk in guten Taten.

Das Land bringt Frucht und bessert sich,

dein Wort ist wohl geraten.

Uns segne Vater und der Sohn,

uns segne Gott der Heilge Geist,

dem alle Welt die Ehre tut,

für ihm sich fürchten allermeist;

und sprecht von Herzen: Amen!

This text has been translated with DeepL (www.deepl.com).

Philipp Hübl

Dear Sir or Madam,

When I received the request from the Bach Foundation, I was somewhat surprised. I am a self-professed atheist and have claimed in my books that there is no such thing as a soul. Now I was being asked to say something on the subject of “Praise thou the Lord, O my spirit.” My first thought was: they have a sense of humour. The request reminded me of a joke we used to ask strangers in primary school: “As an outsider, what do you think about intelligence?” But the request wasn’t entirely out of the blue. Philosophers are outsiders by profession. We look at the world from a great distance. Spinoza calls this “sub specie aeternitatis”, “from the perspective of eternity”. And sometimes this philosophical perspective from the outside can also open up new perspectives, for example on Bach’s Cantata 69.

It deals with at least three major philosophical themes – as do other works by Bach and the writings of Luther. The first theme is the nature of our moral judgement: praise, thanks and criticism are part of this; the second is the inexpressibility or even incomprehensibility of the absolute; and the third is human existence. I will say a few words about each of these three themes. At first glance, they do not seem to fit together, but on closer inspection they do.

Let’s start with moral judgement. Ideally, Kant believed that we should base our everyday moral actions and judgements on universal principles of reason. But Kant also knew human nature and said: “Nothing straight can be made out of the crooked wood of human nature.” Many, perhaps even all of our actions and judgements, according to Kant, do not stem from reason, but from inclinations – today we would say from “emotions” or, more generally, from “moral instinct”. Our moral instinct may well coincide with reason from time to time, but it did not evolve to solve global problems of justice, but rather to enable us to function within a group.

This raises the question: what does our moral judgement actually look like in everyday life? The first observation is that the world is full of moral criticism. Indignation is the dominant emotion, especially on social media: indignation is moral anger. Moral praise, on the other hand, is rare. Ask yourself when was the last time you received moral praise. And when was the last time you praised someone else morally? There is a certain asymmetry here.

There are probably two reasons for this. The first reason is our negative bias. All humans instinctively pay more attention to the negative than to the positive. We are sensitive to potential dangers, such as the misbehaviour of others, so we look very closely at wrongdoing and injustices. When everything is going well, we don’t need to be so precise. The second reason lies in the function of reproach and criticism. When we criticise someone morally, we are interested in the act and the damage it has caused. We ask: Was it intentional, what are the causal connections, how great is the damage? When we praise someone, on the other hand, we often praise a single act, but in fact we are indirectly praising a person’s character. Moral psychologists say that the function of praise is rather to build relationships with people who are close to us, with people with whom we live in a community, and that we want to support and promote their prosocial behaviour.

If we now apply these general observations about the nature of praise and criticism to God, we quickly realise that we are failing. We cannot praise an almighty being and say, “You did a good job with creation. Keep it up!” That is presumptious and un . Nor can one seriously believe that one’s praise promotes God’s prosocial behaviour. The ways of the Lord are inscrutable. They are certainly not changed by praise.

Clearly, the cantata is not literally about praise, but about something related, namely gratitude. The paradox of praising God is reflected by the speaker of the cantata in his performative role. He knows that he cannot literally praise the Almighty, so he does the next best thing: he praises God and at the same time states, “I am incapable of praising. I cannot express my praise adequately. I praise the Lord, but I fail in doing so.”

This rhetorical device brings us to the second philosophical theme dealt with in the cantata: the inexpressibility or incomprehensibility of the absolute. Normally, we can talk about everything and name everything. That is the power of natural language. However, there are two phenomena that give us the impression that our language or our concepts fail us, that we cannot quite put something into words. The first is the absolute: the universe, time, being, God. We can use these terms, as I have just done, but the phenomena themselves remain in a sense incomprehensible, inconceivable. Nietzsche expresses this as follows: “There is nothing that could judge, measure, compare or condemn our existence, for that would mean judging, measuring, comparing or condemning the whole … But there is nothing except the whole!” In order to praise creation or the world as a whole, I would have to relate it to another creation or another world. But this comparison is not available. The absolute eludes our conceptuality.

The second phenomenon of the inexpressible is the subjective. In addition to our language and concepts, we have a second access to the world through subjective experience: “phenomenal consciousness,” as it is called in philosophy. A person who is completely colour blind may know and master all colour words and colour concepts, but they do not know what it means to see a red apple. Seeing an apple has a non-conceptual, non-linguistic content. The same applies to the experience of spirituality. Many believers express their spirituality with words such as hope, trust, closeness, connectedness, presence: these states can also be put into words, but there is always an inexpressible, non-conceptual element resonating within them; something that is expressed in a feeling that cannot be captured in language.

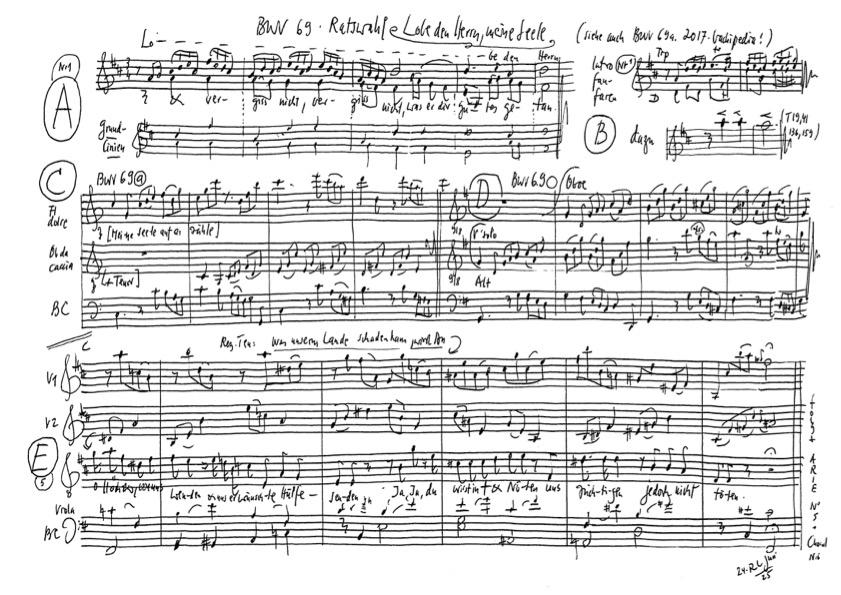

The idea of inexpressibility is also found in another cantata, namely 69a, which in a sense serves as a model for Cantata 69, written two decades earlier. There the problem becomes even clearer. The speaker compares himself to the deaf-mute from the healing of the deaf-mute. He wishes to find the right words of praise, but his mouth is weak and his voice is mute. He wants to speak with a thousand tongues, proclaiming his praise in ever new variations, but he is doomed to failure. This motif of variation also resounds in Cantata 69, literally in the music: the fugue themes vary the praise in countless ways, knowing that the praise will be inadequate.

Music was worship for Bach. One could also say: a non-conceptual form of worship. Music does not make statements in sentences either, but it is the best means of embodying the spiritual experience. The greatness, superhumanity and sublimity of music is also what comes closest to a feeling of spirituality for many atheists.

This brings me to the third theme of the cantata, the question of existence. From the Old Testament, especially from the Book of Ecclesiastes, we know that our life is a breath of wind and even grace on earth is fleeting.

Therefore, praise and thanksgiving on the one hand are always accompanied by fear on the other. In the cantata, praise and fear are two sides of the same coin: they express an un e dependence on something greater. In ancient times, it was fate – Tyche for the Greeks, Fatum for the Romans – for believers, this dependence exists on God. We know that existence is a gift, but at the same time we know that life lasts only seventy years, or eighty at most. And even a good life is marked by work, effort and suffering. This gives rise to the hope for mercy. When we hope, we already assume that we do not have control over the future. Those who hope implicitly say that the fulfilment of their hopes lies beyond their own control and power.

The addressee of this hope is God, but the cantata has a second goal, namely the community of believers. This brings us back to the beginning, to the function of moral judgements. With every moral judgement, whether criticism or praise, we say something not only about other people, but also about ourselves, about our own values and norms. Our moral judgements always have this second, communicative function: we use them for self-expression, in a completely neutral sense of the word. Moral self-expression is unavoidable. And the function of moral communication is not only to praise and criticise actions in order to exchange views on the right values and norms, but also to form a moral community with those who share our values and norms. And we communicate our values and norms within the group: in conversations, in prayers and also in songs.

Against this background, the initially somewhat strange statement about the authorities now becomes understandable. On first reading, one immediately wonders: how does one suddenly get from God to politics? Why do the authorities come into play? God is the creator and sustainer. The authorities mentioned in the cantata, the councillors, perhaps the elector, the king or, more generally, politics – they are not creators, but at least in the secular sense they are sustainers. If the world is well ordered by God, rulers must take this as their model. Creation gives them the duty to care for their citizens. And this is where the prosocial function actually comes into play. Politics is reminded of its mission on earth, the mission of care and charity. We expect good deeds and a better future not only from God, but above all from those in power.

The cantata thus makes two key statements. The first is: “Praise the Lord, my soul, even if you cannot speak!” And the second, expressed in my vocabulary, is: “Praise also the lords of politics, my soul, when they do good, praise them with clear words, for otherwise politicians are only ever criticised, because when you praise them, you can activate their prosocial behaviour and build a connection with them! And if they nevertheless prove to be people of bad character, God will punish them.”

With this in mind, thank you very much for your attention. And remain good people!