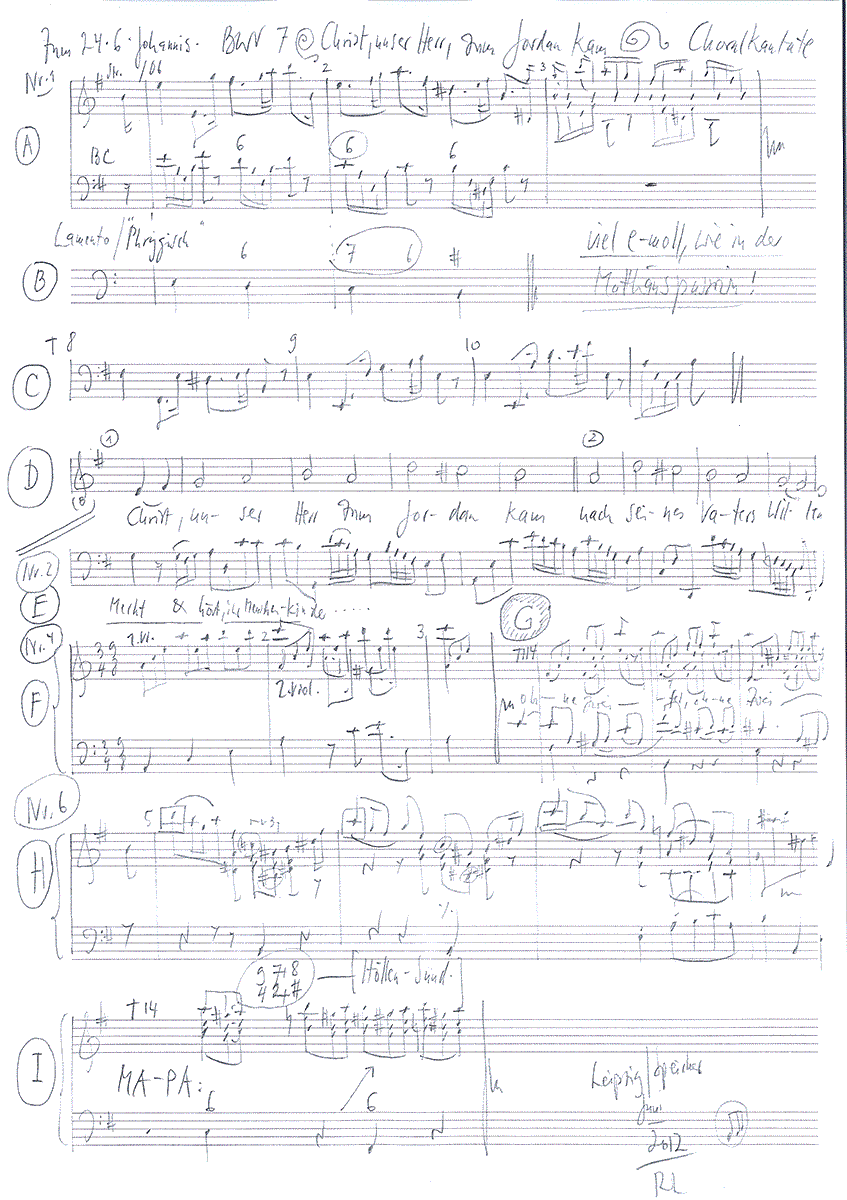

Christ unser Herr zum Jordan kam

BWV 007 // For the Nativity of St. John the Baptist

(Christ did our Lord to Jordan come) for alto, tenor and bass, vocal ensemble, oboe d‘amore I+II, bassoon, strings and continuo

According to Lutheran doctrine, baptism – in addition to communion and penance – belongs to the three sacraments introduced by Jesus and thus to the sacred rites practised by Lutherans after the Reformation. For Johann Sebastian Bach, too, the covenant with God formed through baptism was the cornerstone of his indentity as a human and a Christian. The Nativity of St John the Baptist therefore constitutes one of the most important feasts of the church year, and its profound significance comes to bear in the cantata “Christ, unser Herr, zum Jordan kam” (“Christ did, our Lord, to Jordan come”). Just as Martin Luther in verse one of the hymn, the unknown librettist strived to present Jesus’ baptism by St John as a precedent that is valid for all future members of the church. The cantata’s historic setting on the river Jordan symbolises the “bath” ordained by Jesus that would “wash” the baptised of both the fall of Adam and their own sins.

Would you like to enjoy our videos ad-free? Subscribe to YouTube Premium now...

Workshop

Reflective lecture

Choir

Soprano

Gunhild Lang Alsvilc, Guro Hjemli, Noëmi Tran Rediger, Alexa Vogel

Alto

Jan Börner, Antonia Frey, Alexandra Rawohl, Simon Savoy, Lea Scherer

Tenor

Clemens Flämig, Raphael Höhn, Nicolas Savoy

Bass

Fabrice Hayoz, Philippe Rayot, William Wood

Orchestra

Conductor

Rudolf Lutz

Violin

Renate Steinmann, Dorothee Mühleisen, Christine Baumann, Sabine Hochstrasser, Petra Melicharek, Ildiko Sajgo

Viola

Susanna Hefti, Martina Bischof

Violoncello

Martin Zeller, Hristo Kouzmanov

Violone

Iris Finkbeiner

Oboe

Kerstin Kramp, Andreas Helm

Bassoon

Susann Landert

Organ

Norbert Zeilberger

Harpsichord

Thomas Leininger

Musical director & conductor

Rudolf Lutz

Workshop

Participants

Karl Graf, Rudolf Lutz

Reflective lecture

Speaker

Hardy Ruoss

Recording & editing

Recording date

06/22/2012

Recording location

Trogen

Sound engineer

Stefan Ritzenthaler

Director

Meinrad Keel

Production manager

Johannes Widmer

Production

GALLUS MEDIA AG, Switzerland

Producer

J.S. Bach Foundation of St. Gallen, Switzerland

Librettist

Text No. 1, 7

Martin Luther

Text No. 2–6

Poet unknown

First performance

St John’s Day,

24 June 1724

In-depth analysis

With its solo violin part in perpetual motion, the flowing musical gestures of the introductory chorus appear overwhelmingly inspired by the image of the river Jordan and its baptismal waters. Its majestic, overture-like style and the passionate tonality of E minor reflect the understanding – exclusive to the faithful Christian – that the waters are Jesus’ sacrificial blood; an interpretation which is underscored in the text. In keeping with an old tradition, Bach assigned the melody to the tenor voice, thereby consciously lending an archaic dimension to the elegant orchestral setting. Notably, the words “to drown as well our bitter death” constitute the only line of text to culminate in a sixth chord, thereby portraying death not as the end, but as the path to the “life restored” that brings the chorale to an ecstatic close.

The repetitive, somewhat proselytising style of the bass aria draws its motifs from the speech-like yet driving continuo ritornello which, although less virtuosic, weaves around the vocal part in close contrapuntal style. Following the tenor recitative – with its tangible contrast of “He is from heaven’s lofty throne” with “in meek and humble form descended” – the tenor aria and its two obbligato violins then trace “the Father’s voice” resounding from on high. In light of the movement’s layering of 9⁄8 and 3⁄4 time as well as its use of three solo voices in three vocal sections, it is appreciable that Alfred Dürr interpreted the setting as a musical portrayal of the Holy Trinity celebrated in the text. That the strings in the following bass recitative take up the vocal lines in imitation must surely reflect Jesus’ command to “go forth to all the world”. Surprisingly, the alto aria commences with a vocal motif that is only later taken up by the orchestra – an emphatic pleading to accept God’s offer of mercy that defies all formal conventions. The work’s closing chorale then employs a more familiar cantional setting with soprano melody that is particularly flowing in character despite its old-style stringence. Through the subtly trickling movement in the alto part – suggestive of blood or water – Bach brings the original theme of the cantata full circle.

Libretto

1. Chor

Christ unser Herr zum Jordan kam

nach seines Vaters Willen,

von Sankt Johanns die Taufe nahm,

sein Werk und Amt zu erfüllen;

da wollt er stiften uns ein Bad,

zu waschen uns von Sünden,

ersäufen auch den bittern Tod

durch sein selbst Blut und Wunden;

es galt ein neues Leben.

2. Arie (Bass)

Merkt und hört, ihr Menschenkinder,

was Gott selbst die Taufe heisst!

Es muss zwar hier Wasser sein,

doch schlecht Wasser nicht allein.

Gottes Wort und Gottes Geist

tauft und reiniget die Sünder.

3. Rezitativ (Tenor)

Dies hat Gott klar

mit Worten und mit Bildern dargetan,

am Jordan liess der Vater offenbar

die Stimme bei der Taufe Christi hören;

er sprach: Dies ist mein lieber Sohn,

an diesem hab ich Wohlgefallen,

er ist vom hohen Himmelsthron

der Welt zugut

in niedriger Gestalt gekommen

und hat das Fleisch und Blut

der Menschenkinder angenommen;

den nehmet nun als euren Heiland an

und höret seine teuren Lehren!

4. Arie (Tenor)

Des Vaters Stimme liess sich hören,

der Sohn, der uns mit Blut erkauft,

ward als ein wahrer Mensch getauft.

Der Geist erschien im Bild der Tauben,

damit wir ohne Zweifel glauben,

es habe die Dreifaltigkeit

uns selbst die Taufe zubereit’.

5. Rezitativ (Bass)

Als Jesus dort nach seinen Leiden

und nach dem Auferstehn

aus dieser Welt zum Vater wollte gehn,

sprach er zu seinen Jüngern:

Geht hin in alle Welt und lehret alle Heiden,

wer gläubet und getaufet wird auf Erden,

der soll gerecht und selig werden.

6. Arie (Altus)

Menschen, glaubt doch dieser Gnade,

dass ihr nicht in Sünden sterbt,

noch im Höllenpfuhl verderbt!

Menschenwerk und -heiligkeit

gilt vor Gott zu keiner Zeit.

Sünden sind uns angeboren,

wir sind von Natur verloren;

Glaub und Taufe macht sie rein,

dass sie nicht verdammlich sein.

7. Choral

Das Aug allein das Wasser sieht,

wie Menschen Wasser giessen,

der Glaub allein die Kraft versteht

des Blutes Jesu Christi,

und ist für ihm ein rote Flut

von Christi Blut gefärbet,

die allen Schaden heilet gut,

von Adam her geerbet,

auch von uns selbst begangen.

Hardy Ruoss

“Of the folly of wanting to understand and the unexpected nearness of God”.

Baptism, forgiveness of sins, the blood of Christ, faith are essential for Christian self-understanding. They want to be questioned and explained again and again. In choosing the texts on which his cantatas are based, Bach gave equal consideration to eternal doubt as the driving force of Christian life and the theme of worship. But those who want to understand the text of the cantata “Christ unser Herr zum Jordan kam” (Christ our Lord came to the Jordan) often fall into the abyss of folly, believing that they have understood or can understand. Yet God is closer than we think.

What Bach’s cantata “Christ unser Herr zum Jordan kam” tells is basically a simple story. Jesus comes to the river Jordan; he gets into the water and is baptised by John. A voice from heaven speaks, and what it says can be summarised thus: This is my dear Son; receive him as your Saviour and listen to his teachings from now on. Finally, a dove swoops down and remains above the group picture.

This is what we are told. And for the time being – for this picture – no further explanation is needed, it seems so obvious to us. Of course, this cantata text also speaks of other things: the sacrament of baptism, the blood of Christ, original sin, salvation through faith. This, it became clear to me when I encountered the cantata, definitely requires further explanation. And so I first sought clarification from Martin Luther and opened his “Small Catechism”. I found not only an answer, but also a question to go with it, which moved me: “What does baptism give or help? So Luther asks, and he answers immediately: “It works forgiveness of sins, redeems from death and the devil, and gives eternal blessedness to all who believe it, as the words and promise of God read.

Now this seemed rather strange to me, a baptised Christian, here and now. I hear the words, but they come from far away: sin, death and the devil; word of God, promise and eternal blessedness. And the words remained distant from me, despite echoes of early religious education and later encounters with texts of the Bible and with works of sacred art. And so I had to realise: Luther, the theologian, couldn’t fix it. Then I remembered that perhaps God keeps a few poets for just such cases. And so I found Johann Peter Hebel (1760-1826). The Alemannic poet and popular calendar man of the “Rheinischer Hausfreund” (Rhenish Friend of the House) had at least once attempted to build a bridge between the Bible and literature, between the Word of God and us with his “Biblical Stories” (1824). Similar to Luther’s “Small Catechism”, these retellings were primarily intended for the religious instruction of children. But that could not deter me. With their radiant linguistic power – a wonderful mixture of Luther’s German and Hebel’s Alemannic colloquial language – they would probably also shine home to others who are of good will.

In fact, Johann Peter Hebel’s work is less theological, but very vivid and comprehensible. For John, who baptises Jesus, explains right away what the sacrament is all about; and after all, he has to know. According to John, baptism leads “to the amendment of the mind” and “to conversion from sin to God”. I could at least imagine something under that, namely peace with myself and – if not with the world, then at least – with God. A kind of agreement between my behaviour and what my conscience tells me to do. But how to find this inner peace? Hebel, the narrator, of course has a few key witnesses from those distant days present and people from the people appear who ask precisely this question, which is also on my mind: What is to be done? And John answers: “Whoever has two coats or an abundance of food, let him give to the one who does not have. And to the customs officers John advises, “Do not ask for more than is due you.” Finally, the soldiers also want to know how this promised “amendment of mind” and “turning from sin to God” is to be achieved. And John answers: “Do neither violence nor injustice to anyone, and be content with your pay.”

The path of repentance and the path before repentance

Since Johann Peter Hebel, in his story of the baptism in the Jordan, reckons with clever children, he also has John add that it is easy to see from these three examples what man in general “has to do and not do in his state, office, profession”. Those who do not comply with these demands for moderation, personal responsibility and solidarity with the weaker – as Hebel would probably express it today – do not get away with cheap excuses. Neither “empty conceit” nor “fine speeches and rehearsed prayers” are of any use. Again, translated into today’s terms: Those who violate the commandments of humanity will not excuse themselves with arrogance, rhetoric or PR airs. For repentance means – as simple as that with Hebel: doing “works of justice and mercy”. This opened up a path for me to the cantata text, more precisely to the bass aria, which reads:

“Mark and hear, ye children of men,

what God himself calls baptism!

It must be water here,

But bad water is not alone.

God’s word and God’s spirit

Baptise and cleanse sinners.”

So far, so good, as far as the path of repentance is concerned. But what about the path before repentance? After all, it is this path that leads to the eternal ruin of the “pit of hell”, as the cantata text vividly promises. Where there is a “hell pit”, the devil is not far away, I thought. Soon afterwards, however, I was immersed in stories other than biblical ones. They told of one of Luther’s contemporaries, a real figure who fascinated as much as he frightened: the healer, astrologer, fortune teller, alchemist, black artist Georg Johann Faust (ca. 1480-1540), who was also a doctor of theology.

The popular book with the “History of Doctor Johann Faust” (1587), tells of this man who became a myth. To this day, enlightened minds regard him as a model of modern sin, the epitome of human hubris. He embodies in modern times what, as it says in the cantata, could be meant by the “harm (….) from Adam” – also. And with his life and striving, he bears witness to what the so-called original sin, far from the Bible and God, could – also – be about. Our Doctor Faust, gifted with a “docile and quick-witted head”, but also “rash and foolhardy”, as the “Volksbuch” points out, knows only one goal: he wants everything, and he wants it subito: all the knowledge, all the lust and all the power of this world. And he achieves everything – with the help of the devil and at the price of his soul, which he bequeaths to hell in return. Unlike in Goethe’s later adaptation, where Faust is saved from eternal damnation in the end, Faust from the folk book actually has to pay his tribute. He goes to hell, and not without a certain respect we hear him confess: “So I wanted it”.

Fantasies of omnipotence

But in order to realise his unbridled fantasy of omnipotence, he needs not only the devil but also very worldly allies, strategies and tricks. Therefore, we read, he relied on “his own kind, who used Chaldean, Persian, Arabic and Greek words, figures, formulas, conjurations, interactions and whatever such forms of incantation and sorcery might be called. And these enumerated things were all Dardanian arts, nigromancies, spells, poison-mixings, oracles, conjurations, and however one may mean such books, words, terms. This pleased Dr. Faust well, he speculated and studied in them day and night, (…) became a man of the world and no longer wanted to be a theologian.”

Faust – the myth of his time: one who wants everything and is washed not only with the water of baptism but also with all the waters of black art. Faust – the myth of our time: One we read about daily in all the newspapers, like this: Dr. Faust relied on the likes of Jerôme Kerviel, Kweku Aboli and Bernard Madoff and whatever other such conjurers and magicians might be called. And they were dealing with hedge funds, derivatives, Euro-bonds and Coco-bonds, with structured products, golden parachutes, bail-out parachutes and whatever such forms of conjuring and sorcery might be called. Dr Faust liked that, he speculated and studied in it day and night, and became a man of the world.

So that’s how far I had come in the meantime, reflecting on a cantata text. I exhorted myself to turn back and left Faust where I had arrived in the meantime: in the dark. Because according to Mephistopheles, hell is nothing else, namely “a darkness (…) in which nothing else is to be found but mist, fire, sulphur, pitch and other stench. Thus we devils also cannot know in what shape and manner hell is created (…).” So despite the lantern of my enlightenment, there was nothing more to see here than darkness. And perhaps I still wouldn’t have got any further if a ship hadn’t come out of the blue on which I sailed up and away in good company. It was the “Ship of Fools” of Sebastian Brant (1457-1521), on its way to “Narragonia”, the fool’s paradise. The satirical poem by Luther’s contemporary was published in Basel at carnival time in 1494 and soon became a bestseller throughout Europe. No wonder: you have to pretend to be blind and deaf when reading it in order not to recognise a relative or discover a close acquaintance among the hundreds of fools who populate the ship. Humanly, all too humanly, these people of fools confront us, guided by conceit and arrogance, caught in ignorance and stupidity, driven by arrogance and megalomania. “Nosce te ipsum” – “know thyself”, they call out to us who have long since become passengers, if not crew, of this ship of fools.

While reading The Ship of Fools, I felt very much at home and warmly welcomed into this company, and who knows, perhaps I would still be sailing towards Narragonia if I hadn’t met a brother in spirit who pulled me out of the literary trip. He was sitting right at the front and – surely not by chance – was posted clearly visible on the bow of the ship. It was – yes, it was indeed the bookworm. And he called out to me:

“That I sit in the front of the ship,

That truly has a special grip;

It is not without cause:

On books I set my devotion.

(…)

For it is enough for my mind

when I am surrounded by books.”

The nearness of God

Thus I had suddenly fallen from the healing waters of the Jordan into the treacherous sea of ignorance. The books had made me a fool and thus finally a subject of the most powerful ruler over this earth: folly. Erasmus of Rotterdam (1466-1536), who was also a contemporary of Luther, a baptised Christian and a devout humanist, pays tribute to her, the true queen of the world, in his “Praise of Folly” (1509). It is she, folly, who makes us believe that we can understand life and the world – and thus also the Bible? – could understand. It was responsible for our utopias and optimism, which kept us searching and striving, that is, kept us alive.

But where was God, the Creator, who would ultimately also have to answer for this folly and would be responsible for all the fools? Kurt Marti (*1921), the Bernese contemporary, poet and theologian at the same time, formulated the question succinctly. In three lines and six words, he also gave the answer to the question in a literary aperçu, as it were in passing:

“Why

seek you?

we: thy hiding place”

Maybe God really does keep some poets and poetesses, I thought then, and so finally arrived at me. But with that, we have also arrived. My reflection ends with Martin Luther, who we will now meet again in the cantata, united with Johann Sebastian Bach. No sooner had I put Kurt Marti’s book away than I had Luther’s “Table Talks” in my hands. And we will all want to add nothing more when he lets us know in one of these speeches: “Of the most beautiful and glorious gifts of God, one is musica. (…) The notes bring the text to life. And it drives away the spirit of sadness, as is seen in King Saul (…).”

This text has been translated with DeepL (www.deepl.com).