Bisher habt ihr nichts gebeten in meinem Namen

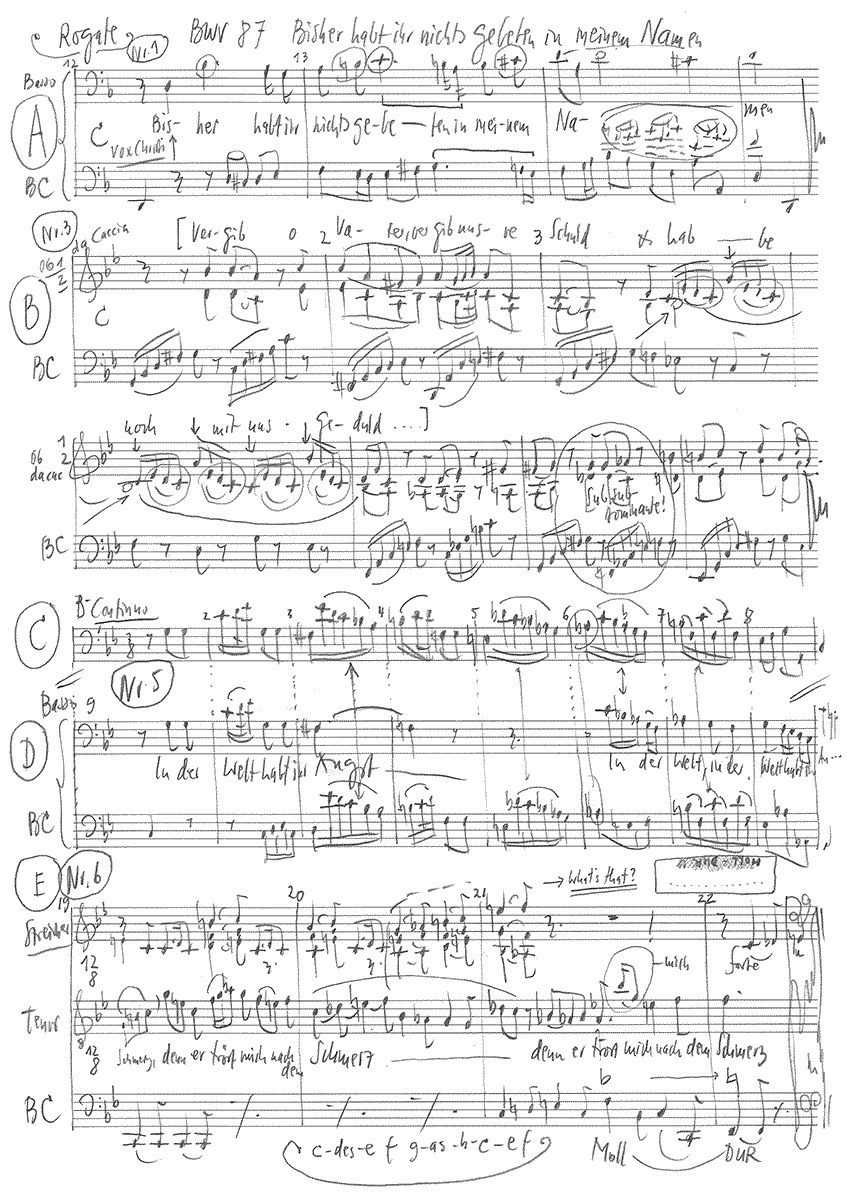

BWV 087 // For Rogate

(Till now have ye nought been asking) for soprano, alto, tenor and bass, oboe I+II, oboe da caccia, strings and basso continuo

Would you like to enjoy our videos ad-free? Subscribe to YouTube Premium now...

Workshop

Reflective lecture

Choir

From the choir of the J.S. Bach Foundation

mezzo-soprano

Alexandra Rawohl

Orchestra

Conductor & cembalo

Rudolf Lutz

Violin

Renate Steinmann, Monika Baer, Claire Foltzer, Elisabeth Kohler, Marita Seeger, Salome Zimmermann

Viola

Susanna Hefti, Olivia Schenkel

Violoncello

Martin Zeller, Hristo Kouzmanov

Violone

Markus Bernhard

Oboe

Katharina Arfken, Natalia Herden

Oboe da caccia

Ingo Müller

Bassoon

Susann Landert

Organ

Nicola Cumer

Musical director & conductor

Rudolf Lutz

Workshop

Participants

Karl Graf, Rudolf Lutz

Reflective lecture

Speaker

Angelika Schett

Recording & editing

Recording date

19.05.2017

Recording location

Trogen AR (Schweiz) // Evangelische Kirche

Sound engineer

Stefan Ritzenthaler

Director

Meinrad Keel

Production manager

Johannes Widmer

Production

GALLUS MEDIA AG, Switzerland

Producer

J.S. Bach Foundation of St. Gallen, Switzerland

Librettist

Text

Christiane Mariana von Ziegler, 1725

Text No. 1, 5

John 16:24 and 33

Text No. 7

Heinrich Müller, 1659

First performance

Rogate,

6 May 1725

In-depth analysis

Composed for Rogation Sunday, the cantata “Bisher habt ihr nichts gebeten” (Till now have ye nought been asking in my name’s honour) opens in the particularly sermonizing and soloistic style that is typical of Bach cantatas BWV 80 to BWV 90. The gospel for that Sunday (John 16:23-30) on Jesus’ parting words to his disciples expresses confidence that prayers will be heard and links this confidence to the resurrected Messiah’s close proximity to God and, by extension, to his followers. This dictum, however, is treated in the libretto less as a sure promise than as a warning to remain steadfast in prayer and devotion – a task in which we mortals frequently fall short by paying no heed to God’s gospel and lapsing anew into a cycle of sin and repentance. Penned by the Leipzig poet and noblewoman Christiane Mariane von Ziegler, the libretto is one of her nine cantata texts that Bach set to music during the hiatus in his chorale cantata cycle between Easter and Trinity Sunday in 1725.

Despite its brevity, the Bible dictum of the opening movement is presented in a dense setting in which the string parts are doubled by oboes to engender the appropriate gravitas. In this movement, the musical substance of the theme gives concrete form to the urgent reminder to observe prayer and to the cross-like burden of selfless entreaty, while the solo part, assigned fittingly to the bass voice, embodies fatherly sternness, majestic serenity – and also a hint of disappointment at humankind’s failure to reciprocate godly love.

In the alto recitative, the somewhat vague dictum is then interpreted as a “Wort, das Geist und Seel erschreckt” (word that heart and soul alarms), thus framing the reticence of the disciples as a deliberate transgression. In the following aria, however, a gentler tone emerges: over simple broken chords in the continuo part, a trusting gesture is offered by the oboes da caccia in a wordless anticipation of the ensuing request for forgiveness. The middle section then takes up the gospel word explaining that the resurrected Christ will no longer talk in parables, but speak plainly. This inspires the human soul, represented by the alto soloist, to ask Jesus to eschew preaching in figures of speech, and instead to intercede on humankind’s behalf – a rather brazen request, despite its elegant presentation in flowing, aria style.

In the accompagnato recitative, the tenor reinforces this shift in attitude by taking to heart the divine promise to the disciples and calling for its realisation: even when “die Schuld bis zum Himmel steigt” (all our guilt unto heaven climbs), the Highest is beseeched to look into the heart of the supplicant and to provide the promised comfort. By setting the final flowing melisma on the word “suchen” (seek) rather than “trösten” (comfort), Bach, too, focuses on the tireless efforts of the Saviour.

In a surprising shift, a second weighty dictum then follows, this time from John 16:33: “In der Welt habt ihr Angst, aber seid getrost, ich habe die Welt überwunden” (In the world ye have fear, but ye should be glad, I have now the world overpowered). In contrast to the paternalistic warning that opens the cantata, Jesus appears here as an empathetic, consoling companion, who, in a buoyant duo setting accompanied only by the continuo, displays a surprising lightness and ease – this saviour is as agile and alert as ever, and readily honours his promise.

This in turn establishes an aura of comfort and calm, allowing the tenor to embark on a floating siciliano aria in the relaxed key of B-flat major. The opening line of “Ich will leiden, ich will schweigen” (I will suffer, I will keep silent), although resigned in and of itself, thus acquires a sense of assurance and comfort; accordingly, the orchestral introduction is pervaded by a gentleness of tone that is also sustained in the noble cantilena of the tenor. This intense moment of joy requires neither a da capo nor endless repetitions; rather, it is rendered as a soulful epiphany through its brevity and emotional clarity.

The following closing chorale sets a fitting text by Heinrich Müller from 1659 (“Muß ich seyn betrübet, so mich Jesu liebet” – Must I be so troubled? For if Jesus loves me) to the famous melody of “Jesu, meine Freude” (Jesus, my true pleasure). Bach’s simple arrangement, however, relieves the hymn and text of none of the gravity: rather than alleviating suffering, love serves only to sweeten the pain – a small but significant mercy.

Libretto

1. Dictum (Bass)

»Bisher habt ihr nichts gebeten in meinem Namen.«

2. Rezitativ (Alt)

O Wort, das Geist und Seel erschreckt!

Ihr Menschen, merkt den Zuruf, was dahinter steckt!

Ihr habt Gesetz und Evangelium vorsätzlich übertreten,

und diesfalls möcht’ ihr ungesäumt in Buß und Andacht beten.

3. Arie (Alt)

Vergib, o Vater, unsre Schuld,

und habe noch mit uns Geduld,

wenn wir in Andacht beten

und sagen: Herr, auf dein Geheiß,

ach rede nicht mehr sprüchwortsweis,

hilf uns vielmehr vertreten!

4. Rezitativ (Tenor)

Wenn unsre Schuld bis an den Himmel steigt,

du siehst und kennest ja mein Herz,

das nichts vor dir verschweigt;

drum suche mich zu trösten!

5. Dictum (Bass)

«In der Welt habt ihr Angst; aber seid getrost, ich habe die

Welt überwunden.»

6. Arie (Tenor)

Ich will leiden, ich will schweigen,

Jesus wird mir Hülf erzeigen,

denn er tröst’ mich nach dem Schmerz.

Weicht, ihr Sorgen, Trauer, Klagen,

denn warum sollt ich verzagen?

Fasse dich, betrübtes Herz!

7. Choral

Muß ich sein betrübet?

So mich Jesus liebet,

ist mir aller Schmerz

über Honig süße,

tausend Zuckerküsse

drücket er ans Herz.

Wenn die Pein sich stellet ein,

seine Liebe macht zur Freuden

auch das bittre Leiden.

Angelika Schett

Not missing oneself as a human being

Bach’s cantata “Bisher habt ihr nichts gebeten in meinem Namen” (BWV 87) reflects on a condition of successful human existence: the renunciation of the idea of being able to find fulfilment as a supposedly autonomous individual.

The chorale in the cantata “Bisher habt Ihr nichts gebeten in meinem Namen” (BWV 87) promises comfort. It is comfort that we need, ask for, sometimes even implore in life when we are desperate, sad or at a loss. People of faith then turn to God. In this turning, they bring up what makes them so stunned. I am not thinking of familiar prayers, but of their own words that seek to express what is personally distressing. But since God is God, he will not satisfy needs or become a problem solver or comforter, as the Tübingen theology professor Karl-Josef Kuschel puts it.

How can one find comfort at all under these circumstances? It is the language with which I express, try to convey, what cannot be borne alone. When I pray or ask, I cannot stumble along speechlessly. However, I do not have to resort to elaborate formulations, I only have to manage to express what exactly I am lacking. It is the language, however simple it may be, with which I turn to God or even to a human being in order to communicate what was or is agonising. This language already contains knowledge in itself and can thus contribute to a kind of consolation. Psychotherapists also make use of this. With their means, they get people to put into words what is supposedly unspeakable. How many fall silent in the face of what has happened to them, what depresses them? Experience shows that this does no one any good.

The imperative: Rogate: Pray / Ask has, in my eyes, above all to do with this ability to speak. The pivotal point of my reflections is the petition, which must express our dependence and our dependence on other people – in a very elementary way – if it wants to be heard. But who finds it easy to ask in this sense? The request is the admission of one’s own neediness, also helplessness in this special moment. One can no longer manage on one’s own.

Children, as long as they grow up in good circumstances, still find it easy to ask for something, for example when they are afraid of the dark night and ask their parents to stay there until they fall asleep. As an adult, you don’t usually do that any more, even if you feel like it, often not even to a good friend. Because if you make such an existential request, you have to show your colours and risk exposing yourself a little in front of your friend. What if you fear, whether justified or not, that you will be misunderstood or, even worse, that you will get on his nerves? What if you are afraid of showing yourself weak and losing the respect and appreciation of the other person? What if one slips from asking to begging and loses one’s dignity in the process? To better illustrate what I am talking about, I went in search of examples, of which I have chosen two for today. The first I found in the book by philosopher Peter Bieri entitled: A Way of Living – On the Diversity of Human Dignity.

Bieri tells of a fictional couple. One Sunday evening, the wife takes her husband to the hospital – he is about to have a minor operation. “See you,” she says after bringing him into the room, and at the same time puts her hand on the door handle. “Can’t you stay a little longer?” he asks, startled by how busy his voice suddenly sounds. With this pleading question, says Peter Bieri, the man does not yet forfeit his dignity. He is still only expressing a request, a wish that she can fulfil. However, the woman replies as she pulls the door open further: “Well, I have to get up early tomorrow.” “But,” the man says in response, “it’s only 7:00.” First it was a plea, now it is a begging. Even if the woman did stay a little longer, it would be a handout. Her husband is so dependent on her presence that he is risking his dignity.

What does this show? I can fail with my request. That makes it risky. My need is compounded by shame and disappointment. I have to learn that I have insubordinately bothered the person close to me with my request. With my request, I cast a light on him that, for better or for worse, brings him into my field of vision differently. Does he make me feel my weakness by letting his superiority as a grantor shine through? Then I not only look stupid with my request, but also lose my trust in the other person. Let us speculate how it could have turned out in the good case between the man and the woman in the hospital. She would have noticed from his request and from his strained voice that he needed her, quite existentially, that evening in the hospital. She would have sat with him, held his hand, or maybe told him something, nothing significant at all, but it could have conveyed to the person asking, “I’m not leaving you alone at this moment.” Of course, she would have left later too, but he would have been comforted and able to face the procedure the next day with confidence. In this way, his request would have been fulfilled in the truest sense of the word, it would have been worth the risk.

Sometimes it is not even so clear what one is actually asking for. In the case of a serious illness, a death or financial ruin, it is concrete, comprehensible reasons that, to a certain extent, legitimise the request for assistance. In such situations, people close to us offer their help even without a prior request. But what about the imprecise conditions that afflict us much more often? When it’s more something like, “I’m not feeling well, please listen to me, let me be confused, please help me figure out what this is all about.” When that is allowed to come up in dialogue, it is already redemptive. Who doesn’t sometimes wish for a person who understands and accompanies them on the paths of confusion? And what luck to know such a person at one’s side.

The writer Heinrich Böll once put it this way in a conversation: “The fact that we actually all know, even if we don’t admit it, that we are not at home on this earth, that we are not completely at home, that we still belong somewhere else and come from somewhere else – I can’t imagine a person who doesn’t realise, at least temporarily, hourly, daily or even just momentarily, that he doesn’t quite belong on this earth.”

Böll here addresses homelessness on earth, which can translate into sadness. We are only here temporarily. This knowledge makes itself felt again and again beyond our concrete, directly perceptible hardships. This knowledge makes people pray or ask. May someone else be with us, God or a human being. In his novel Our Souls by Night, the American writer Kent Haruf tells us how this can be expressed in literature, admittedly in an idiosyncratic way. It goes like this:

One evening, Addie Moore, a widow, rings the doorbell of Louis Waters, himself also a widower. They live a block apart, both are retired and don’t know each other very well. He finds her appealing, always has, that’s all.

She says, “You’re probably wondering what I want from you. “

“Well,” he replies, “you probably didn’t come here to tell me I have it nice here.”

“No,” she says, “I came to ask you for something, something like a proposal. But not a marriage proposal.”

“I didn’t expect that either,” he says.

She: “But it’s going in that direction. Only I don’t know if I can do it. I’m suddenly getting cold feet.”

“I’m listening,” he says.

She: “I mean that we are both alone. We’ve been left to ourselves for far too long. For years. I’m lonely. I thought maybe you were too. That’s why I wanted to ask if you would come and spend the night with me. And talk to me. It’s not about sex,” she adds. “I haven’t felt like having sex for a long time. I’m talking about getting through the night. Lying in bed together – all night. Nights are the worst, don’t you think?”

In the book, the arrangement comes about, he visits her in the evening and disappears in the morning. During the nights they tell each other about their lives, the good and the difficult, until they are tired and fall asleep.

Once he says, “What you suggested to me seems so brave.”

“Yes,” she says, “but if it hadn’t worked, I wouldn’t have been any worse off than before. Except for the humiliation of having gotten myself turned down. But I didn’t think you’d be blabbing it all over the place, so only you and I would have known about it if you’d said no.”

The example may seem a little strange, and it is literature. It’s just that something important is being addressed. The widow in this narrative does not submit to the norm. Life is more important to her, and so she dares to make this unheard-of but then heard proposal. Both are no longer alone at night. It is then the society of the village in which they live that disapproves of this courageous step.

The others, society. Who can and may still express their dependence and neediness in terms of sympathy and comfort without losing face? We live in the age of “autonomy mystification”, this somewhat cumbersome term is used by the Heidelberg psychotherapist Arnold Retzer.

“Autonomy mystification”: to manage everything under one’s own steam, to never show oneself to be needy, that is the motto in our latitudes. The superficial gloriousness of the circumstances of life here often obscures the view of inadequacy and dependence, one’s own and that of others. Throughout a person’s professional life, those who are sure of victory have the edge anyway. Hesitation and hesitation, reflection and asking for advice, tend to be denounced as weakness, although both would be quite appropriate from time to time. Politically, acting on the spur of the moment can even be dangerous.

And privately? When we meet with friends and acquaintances, do we focus more on the successful life, even celebrate it a little in front of each other, so that nothing incriminating can be brought up? Or do we prefer a round in which the unsuccessful and the needy may be said here and there, seriously and not just anecdotally? In such a group, no one will deny, one feels more familiar, more genuine and, above all, much more alive.

And otherwise? “I don’t want to be a burden on anyone,” older and elderly people often say. They would rather retire from life. How can one suddenly – having become old and frail – ask for help if one has not done so all one’s life? Everything that has even the appearance of dependency has become socially discredited. It is, to use such an unpleasant word, totally uncool. But what happens to us as human beings on this earth when we no longer ask for help? When we no longer want to take the risk of asking? We would rather perish than express our dependence on God or a human being in the form of a request. And then, at some point in our lives or at the end of our existence, we are forced to depend on help and would rather wish for death in such a situation. What can we do to counter this?

On this subject, Goethe, who, incidentally, was himself a great admirer of Bach, said:

“Voluntary dependence is the most beautiful state, and how would that be possible without love?”

In my understanding, that would be dependence with dignity, which we are so afraid of losing when we ask for something that exposes our vulnerability.

Rogate: Ask! It is a risk, but one that we should take in order not to miss ourselves as human beings.

I cannot introduce the cantata we are about to hear again, and which now justifiably leaves me silent, more beautifully than with the remark of one of Bach’s four famous sons, Carl Philipp Emanuel:

“My father’s music has higher intentions; it is not meant to fill the ear, but to set the heart in motion.”

This text has been translated with DeepL (www.deepl.com).