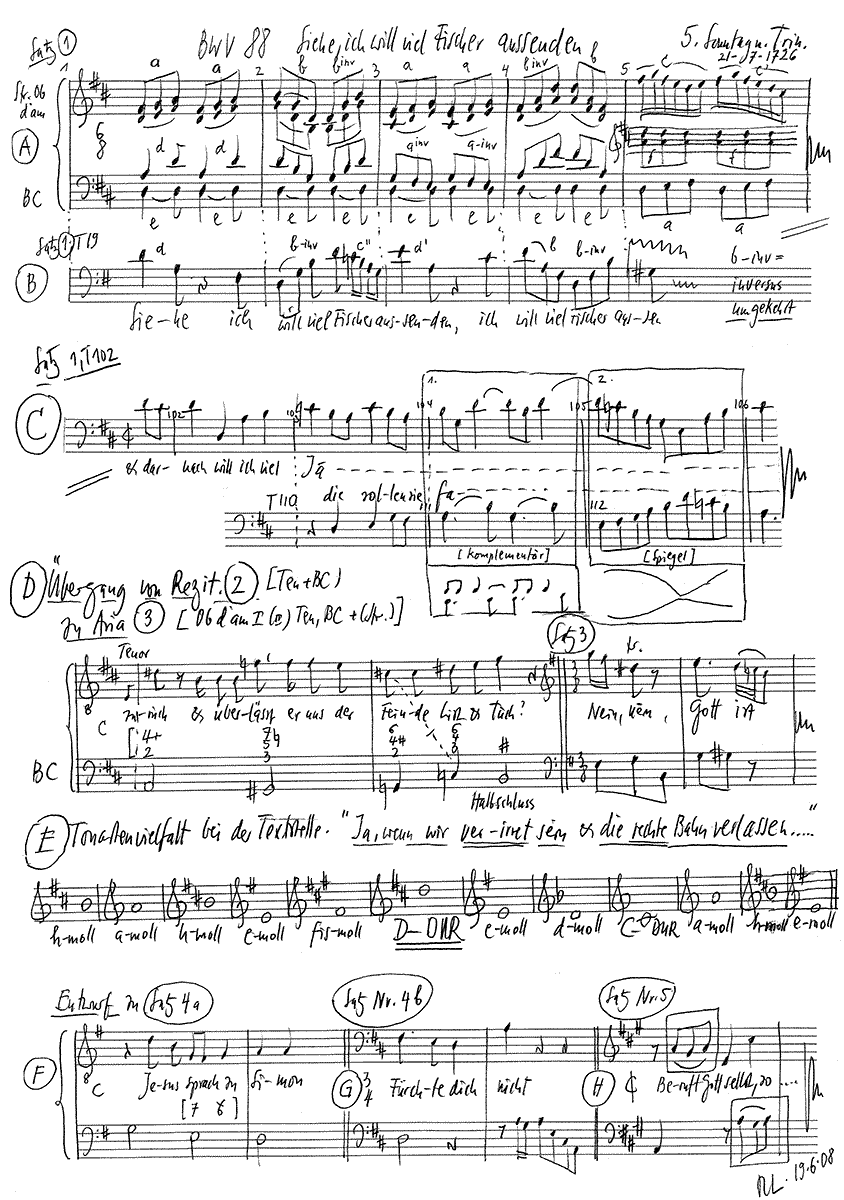

Siehe, ich will viel Fischer aussenden

BWV 088 // For the Fifth Sunday after Trinity

(See now, I will send out many fishers) for soprano, alto, tenor and bass, horn I+II, oboe d’amore I+II, taille, bassoon, strings and continuo.

Would you like to enjoy our videos ad-free? Subscribe to YouTube Premium now...

Workshop

Reflective lecture

Orchestra

Conductor & cembalo

Rudolf Lutz

Violin

Renate Steinmann, Monika Baer

Viola

Susanna Hefti

Violoncello

Ilze Grudule

Violone

Iris Finkbeiner

Oboe d’amore

Luise Baumgartl, Dominik Melicharek

Oboe da caccia

Esther Fluor

Taille

Esther Fluor

Bassoon

Susann Landert

Horn

Olivier Picon, Jurij Meile

Musical director & conductor

Rudolf Lutz

Workshop

Participants

Karl Graf, Rudolf Lutz

Reflective lecture

Speaker

Isabelle Graesslé

Recording & editing

Recording date

06/20/2008

Recording location

Trogen

Sound engineer

Stefan Ritzenthaler

Director

Meinrad Keel

Production manager

Johannes Widmer

Production

GALLUS MEDIA AG, Switzerland

Producer

J.S. Bach Foundation of St. Gallen, Switzerland

Librettist

Text No. 1

Quote from Jeremiah 16:16

Text No. 2, 3, 5, 6

Poet unknown

Text No. 4

Quote from Luke 5:10

Text No. 7

Georg Neumark, 1657

First performance

Fifth Sunday after Trinity

21 July 1726

Libretto

Erster Teil

1. Arie (Bass)

»Siehe, ich will viel Fischer aussenden, spricht der Herr.

Siehe, ich will viel Fischer aussenden, spricht der Herr,

die sollen sie fischen.

Und darnach will ich viel Jäger aussenden,

die sollen sie fahen auf allen Bergen und auf

allen Hügeln und in allen Steinritzen.«

2. Rezitativ (Tenor)

Wie leichtlich könnte doch der Höchste uns entbehren

und seine Gnade von uns kehren,

wenn der verkehrte Sinn sich böslich von ihm trennt

und mit verstocktem Mut

in sein Verderben rennt.

Was aber tut

sein vatertreu Gemüte?

Tritt er mit seiner Güte

von uns, gleich so wie wir von ihm, zurück?

Und überläßt er uns der Feinde List und Tück?

3. Arie (Tenor)

Nein, nein!

Gott ist allezeit geflissen,

uns auf gutem Weg zu wissen

unter seiner Gnaden Schein.

Ja, ja! wenn wir verirret sein

und die rechte Bahn verlassen,

will er uns gar suchen lassen.

Zweiter Teil

4.a Rezitativ (Tenor)

Jesus sprach zu Simon:

4.b Arioso (Bass)

Fürchte dich nicht, denn von nun an wirst du Menschen fahen.

5. Arie (Duett Sopran, Alt)

Beruft Gott selbst, so muß der Segen

auf allem unsern Tun

in Übermaße ruhn,

stünd’ uns gleich Furcht und Sorg entgegen.

Das Pfund, so er uns ausgetan,

will er mit Wucher wieder haben;

wenn wir es nur nicht selbst vergraben,

so hilft er gern, damit es fruchten kann.

6. Rezitativ (Sopran)

Was kann dich denn in deinem Wandel schrecken,

wenn dir, mein Herz, Gott selbst die Hände reicht?

Vor dessen bloßem Wink schon alles Unglück weicht,

und der dich mächtiglich kann schützen und bedecken.

Kommt Mühe, Überlast, Neid, Plag und Falschheit her

und trachtet, was du tust, zu stören und zu hindern,

laß kurzes Ungemach den Vorsatz nicht vermindern.

Das Werk, so er bestimmt, wird keinem je zu schwer.

Geh allzeit freudig fort, du wirst am Ende sehen,

daß, was dich eh’ gequält, dir sei zu Nutz’ geschehen.

7. Choral

Sing, bet und geh auf Gottes Wegen,

verricht das Deine nur getreu

und trau des Himmels reichem Segen,

so wird er bei dir werden neu:

denn welcher seine Zuversicht

auf Gott setzt, den verläßt er nicht.

Isabelle Graesslé

“From Hunted to Hunter:

God’s Plan with Man”

The path from damnation to grace – yesterday and today

It was on a summer evening about 20 years ago …

Being north of the Arctic Circle, it was still light, and a soft light scattered rose petals on the calm waters of the fjord. Crammed into a boat, clumsily handling bait and hooks, I tried my best to fish. It was to be my first and last attempt.

The thought of having to kill the catch, a very skinny fish by the way, made my blood run cold, so I threw the unfortunate fish back into the water as fast as I could.

One has to admit that fishing – and even more so hunting – are acts of violence, even if their practice was necessary for the survival of mankind in primeval times. They are gestures of attack in which the target becomes the prey, the trembling life pursued to the threshold of death.

The opening aria of the cantata BWV 88 is about nothing other than this breathless, threatening, merciless pursuit: “Behold, I will send forth many fishermen, saith the Lord, and they shall fish them. And afterward I will send forth many hunters, and they shall catch them upon every mountain, and upon every hill, and in all the clefts of stones.”

Why this stiff-necked danger? Simply because, it seems to me, the opening aria is the exact repetition of an oracular saying of the prophet Jeremiah (16:16), the lone prophet of Israel.

A frightening oracle that applies to all those who dare to rebel against the divine will. All these culprits are sought out, persecuted, driven from the furthest corners and the darkest crevices. For nothing can resist the divine voice.

However: the logic of eternity cannot correspond to that of man. For the biblical stories tell of God always moving from wrath to forgiveness, from forgiveness to grace, from grace to rapturous amazement. As if nothing is ever fixed for eternity, because eternity is precisely this: a letting go of time, a necessary and infinitely beneficial distancing. Incidentally, as if to emphasise this letting go, this distancing, the melody runs light-footedly over the heights of the hills.

The hunt for the culprits recedes a little more into the background with each step, and when the last notes of the aria fade away, the exhausting chase has become a light dance, the rough rocks have turned into gentle hills.

In complete reversal, the word of damnation now resounds as a word of mission: “Fear not; for from now on you will catch men (fahen)”. You, who before were a prey sought to the innermost parts of the earth, now breathe in the free air, you yourself have become a catcher of men. In fact, the approaching kingdom of God is nothing other than conversion, a conversion in the encounter.

Persecution has become dance; a spark of grace ignites briefly and shines in the evening, like the rose petals dancing on the still waters.

What has happened? The word of condemnation has turned into a word of grace: “If God himself calls, then the blessing / must rest on all our doings / in abundance.” I would like to see in this reversal of the divine word the endeavour to lift man once again and again above his earthly and sometimes so earth-heavy identity. It is a desire of God to lead man to that origin which is more spacious than all the landscapes of the world. The blessing, this reversal in the divine, invites the renewal of our days of life.

In ancient Israel, at the moment of the blessing, the priests, their faces turned towards the Ark of the Covenant, spoke these ritual words to the assembled faithful: “God of our fathers, you who commanded us to bless your people with love.”

And at that very moment they raised their hands to shoulder height and spread their fingers. Why this gesture? Because, as the sages teach, the divine Presence, the Beautiful Presence, had decided to settle on the unfolded fingers of the priests, signs of an attention turned to the other, of a love that is not self-interested and respectful, signs of a presence that hopes for the other.

Basically, all the harmonies of this cantata revolve like concentric circles around this reversal, as if the interplay of the singing voice and the harmonious text contributed to calming human fears: “How easily the Most High could spare us / and turn his grace away from us, / (…)”.

Do we have to perform rituals, prayers, liturgies or pilgrimages – and may they only take place within ourselves – in order to participate in this harmony of grace and peace? It is probably more about letting go, freeing ourselves from the heaviness of the world, walking with light feet over mossy hills. To let go of the ropes that suffocate, of the black pincers that oppress, of those little rodents that nestle tenaciously in the pit of the stomach….

The only necessary nourishment for this journey inwards is humility. How could it be otherwise, since this conversion leads to the renewal of our days? As in the beginning of the world … The intimate space of the soul opens up to the outermost and ultimate.

Each and every one of us sometimes experiences such moments, which, by the way, do not necessarily have to be associated with the divine. And these moments of eternity, wonderful gifts, make us receptive to the mysteries of the world.

Indeed, if the reversal of the divine word means that we are led into a kind of time outside of time, to the point of our own reversal, then, like the newborn, we must learn to comprehend the languages of the world, its knowledge and its secrets. Just like those fishermen, called by the prophet from Nazareth, at that time, on a stormy day, on the shore of the Galilean lake. He calls them and they follow him, strangely obedient, ready to turn away from themselves, to go on, to give flavour and spice to their lives, they who from now on are the salt of the earth; to radiate light, they who are henceforth to be the light of the world. A strange calling, which is for those men who are so little gifted for spiritual initiations, but rather probably a little uncouth, fearful and naive. Like the first among them, Simon.

Simon, our double, our brother, this persistent one, the first of a new race of God-walkers, constantly wavering between fear and boldness, between restlessness and faith. Simon, who promises to lay down his life for his Master, throwing himself, as it were, in advance, body and soul, into death, just as he had thrown himself at dawn onto the grey waters of the lake to walk in the footsteps of the Nazarene. Simon, unable to face reality, to face the absence of the Master, the definitive absence. Simon, who emerges from his night at cockcrow and finally understands that the passage is complete.

Simon, our double: in his calloused hands, as in ours, only fragments of words remain, sparks of memory, and, as tonight, offered like a gift in a silk-covered jewellery box, the harmony of inspired music.

Even when I was a pastor, I resisted for a long time the call of the Gospels to become a fisher of men. Today, I no longer understand this call as a propaganda tool that can serve the most criminal ideologies. Rather, it is a matter of being renewed by the reversal of the divine word.

The word has been fulfilled, it is fulfilled today and it will be fulfilled again and again, every time a spark lights up the gaze we cast on the other. Fishers of men, that simply means going and awakening the other, because one day one has found oneself awakened, renewed.

“Jesus said to Simon: (…)”. But what does Jesus say to Simon? We don’t know, because the music takes the place of the echoing words … and if, in fact, this had no meaning at all? and if, in fact, what was said there about the disciple’s future becomes meaningless, in the face of this dialogue whose words are not reproduced for us?

Jesus turns to Simon. Everything is contained in this intense confrontation in which the awakener is awakened. Everything is contained in it. In the silence of the beginnings. In this moment in which the heaviness of our days dissipates, as a fog passed away, in the world’s morning.

I would like, if it is possible, to let this silence reverberate at the end of the cantata. Before the necessary applause with which we express our joy to the artists and our gratitude for their talent, I would like to let the silence resound.

That inhabited silence that will carry us for a long time, just as at the end of a cruise, when one has ground under one’s feet again, one continues to “lurch” for a few hours or even days. This silence arises from the confrontation between the prophet and the fisherman, between the fear of death and the spark of life.

I would like, if it is possible, for us to give space to this revelatory silence; it is the bearer of all knowledge of the world, unique experience of time in eternity before things take their course again and fragment in an inexorable time-binding.

After listening to the angelic harmony, the silence of the Beautiful Presence, fragment of eternity, nestles in the depths of our being, and this secret shining will cross us with its glow. For in this unspent silence, the wonderful cantata of today will then reveal a part of the whole work, of the complete work, of the finished work … and we will find in it a fragment of our origin.

This text has been translated with DeepL (www.deepl.com).