Was soll ich aus dir machen, Ephraim

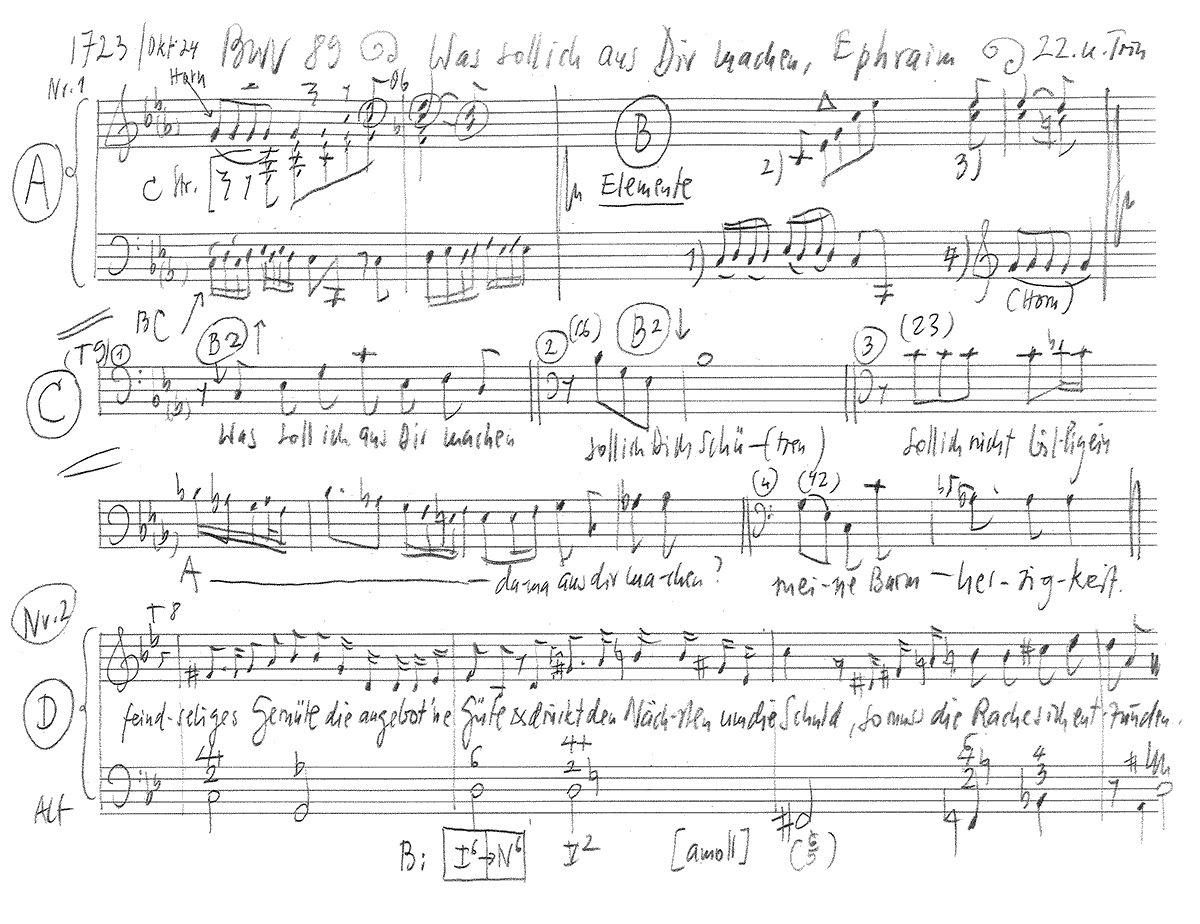

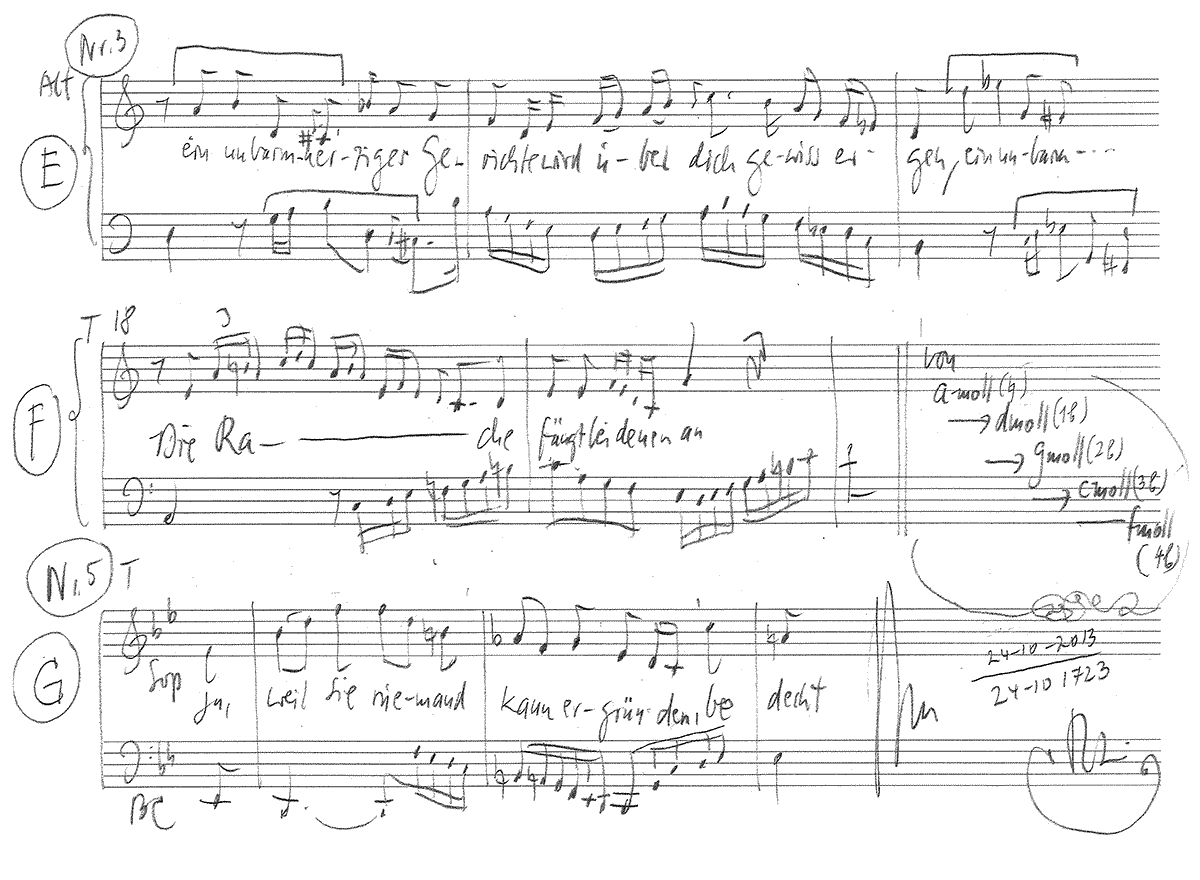

BWV 089 // For the Twenty-second Sunday after Trinity

(What shall I make of thee now, Ephraim?) for soprano, tenor and bass, corno da caccia, oboe I+II, bassoon, strings, organ and continuo

Would you like to enjoy our videos ad-free? Subscribe to YouTube Premium now...

Workshop

Reflective lecture

Orchestra

Conductor & cembalo

Rudolf Lutz

Violin

Renate Steinmann, Monika Baer, Monika Altorfer, Sabine Hochstrasser, Martin Korrodi, Olivia Schenkel

Viola

Susanna Hefti, Ulrike Kaufmann, Martina Zimmermann

Violoncello

Martin Zeller, Hristo Kouzmanov

Violone

Iris Finkbeiner

Oboe

Kerstin Kramp, Andreas Helm

Bassoon

Susann Landert

Corno da caccia

Olivier Picon

Organ

Nicola Cumer

Musical director & conductor

Rudolf Lutz

Workshop

Participants

Karl Graf, Rudolf Lutz

Reflective lecture

Speaker

Thomas Cerny

Recording & editing

Recording date

10/25/2013

Recording location

Trogen

Sound engineer

Stefan Ritzenthaler

Director

Meinrad Keel

Production manager

Johannes Widmer

Production

GALLUS MEDIA AG, Switzerland

Producer

J.S. Bach Foundation of St. Gallen, Switzerland

Librettist

Text No. 1

Quote from Hosea 11:8

Text No. 2–5

Poet unknown

Text No. 6

Johann Heermann, 1630

First performance

Twenty-second Sunday after Trinity,

1723

In-depth analysis

First performed on 24 October 1723, cantata BWV 89 technically belongs to Bach’s first cantata cycle in Leipzig. Nonetheless, certain stylistic characteristics, particularly the sparse scoring and soloistic texture, as well as peculiarities in the notation of the existing original parts suggest the work stems at least partially from a Weimar-era composition that the composer reworked for his new position in Leipzig.

In particular, the distinctive but not consistently independent horn part in the introductory bass aria appears to be a last moment addition in Bach’s own hand; here, the horn underscores the intensity of the Godly tirade, presented in the words of the prophet Hosea, that expresses rage at Israel’s failure to keep His commandments. In this setting, the rumbling continuo figures, terse ascending leaps in the strings, prominent repeated horn notes and ponderous general rests illustrate the inner conflict of the heavenly Father, whose heart is torn between disciplinary severity and indulgent understanding. In this baroque portrait of a ruler, majesty and mercy are closely intertwined – just as earthly power and divine order were seen to be correlated.

The alto recitative self-critically confirms the depravity of human souls, who, in light of their innumerable sins, should rightly be considered enemies of God. The reference to those who shift “the guilt” to their neighbours is then explored further in the aria: unlike in Hosea’s philippic, it is not blasphemous idolatry that has stoked God’s ire, but rather, as described in the parable of the unforgiving servant in Matthew 18, the double standards applied to oneself and to others. Set for alto and continuo only, the opening of the aria evokes the “unbarmherzige Gericht” (unforgiving word of judgment) and practically glorifies divine wrath in long melismas ere the B section states the decision of the heavenly authority in unmistakeable terms: “Die Rache fängt bei denen an, die nicht Barmherzigkeit getan” (For vengeance will with those begin, who have not mercy exercised).

In this dire situation, the soprano recitative comes across as a cathartic new beginning: “Wohlan! Mein Herze legt Zorn, Zank und Zwietracht hin” (Well, then, my heart will lay wrath, rage, and strife aside). In this brief setting, what can still be achieved through Martin Luther’s theological break with the cycle of sin and penance – even centuries after the posting of his ninety-five theses – is made impressively clear. Indeed, when even the most willing repenters despair at the weight of their own sin, it is belief in Christ’s sacrifice on our behalf that halts the merciless law of the Old Covenant – a notion that not only empowers humans to embrace the practice of true Christian love (celebrated here by Bach in a magically set closing phrase), but also humanises God himself to a certain extent.

In the following soprano aria with obbligato oboe, this realisation enables the soloist to present a bold argument in musically spirited language. In a theme fitting for the trade city of Leipzig with its renowned law school, a tough negotiation is underway here, despite the setting’s harmless dance-like style. Indeed, the pointed question “Gerechter Gott, ach rechnest du?” (O righteous God, ah, countest thou?) implies that a truly Christian concept of God is irreconcilable with a fastidious prosecutor who keeps score of every transgression. But should this just God nonetheless quantify our sins, may he then book them against the far weightier sum of the blood shed by Jesus.

With a return to the collected mood of G minor, the closing chorale reiterates this relationship between self-knowledge and trust in redemption. In the closing phrase on overcoming “Tod, Teufel, Höll und Sünde” (Death, devil, hell, and error) there even lies – contrary to Ernst Bloch’s polemical thesis of a “German quietism” inherent in Lutherism – an energetically activating moment.

Libretto

1. Arie (Bass)

»Was soll ich aus dir machen, Ephraim?

Soll ich dich schützen, Israel?

Soll ich nicht billig ein Adama aus dir machen und dich wie Zeboim zurichten?

Aber mein Herz ist anders Sinnes, meine Barmherzigkeit ist zu brünstig.«

2. Rezitativ (Alt)

Ja, freilich sollte Gott

ein Wort zum Urteil sprechen

und seines Namens Spott

an seinen Feinden rächen.

Unzählbar ist die Rechnung deiner Sünden,

und hätte Gott auch gleich Geduld,

verwirft doch dein feindseliges Gemüte

die angebotne Güte

und drückt den Nächsten um die Schuld;

so muß die Rache sich entzünden.

3. Arie (Alt)

Ein unbarmherziges Gerichte

wird über dich gewiß ergehn.

Die Rache fängt bei denen an,

die nicht Barmherzigkeit getan,

und machet sie wie Sodom ganz zunichte.

4.Rezitativ (Sopran)

Wohlan! mein Herz legt Zorn, Zank und Zwietracht hin;

es ist bereit, dem Nächsten zu vergeben.

Allein, wie schrecket mich mein sündenvolles Leben,

daß ich vor Gott in Schulden bin!

Doch Jesu Blut

macht diese Rechnung gut,

wenn ich zu ihm, als des Gesetzes Ende,

mich gläubig wende.

5. Arie (Sopran)

Gerechter Gott, ach rechnest du?

so werde ich zum Heil der Seelen

die Tropfen Blut von Jesu zählen.

Ach rechne mir die Summe zu!

Ja weil sie niemand kann ergründen,

bedeckt sie meine Schuld und Sünden.

6. Choral

Mir mangelt zwar sehr viel,

doch, was ich haben will,

ist alles mir zugute

erlangt mit deinem Blute,

damit ich überwinde

Tod, Teufel, Höll und Sünde.

Thomas Cerny

“Daring to live a meaningful life”

Between the threats of the Old Testament God and the sublime zeal of the struggling human being, the text of the cantata BWV 89 “What shall I make of thee, Ephraim?” is able to give an idea of the conditions of the possibility of this paradise.

Reflections unfold playfully like colourful butterflies in a free space of thought that opens up and expands at will if one wants to understand fundamental things. We humans can think anything, unlimitedly, even the impossible. To ensure that this does not become completely boundless, Kant proposed three maxims, which will be briefly explained here following Hans Saner (Hans Saner, “Nicht-optimale Strategien”, Essays zur Politik, Lenos Verlag, Basel 2002):

Thinking for oneself, a principle of the Enlightenment: fearlessly detaching oneself from the pre-conceived and creating something new, something independent.

Thinking in the place of another – cultivating communication in thinking, exchanging ideas, so that through plurality narrow-mindedness, one-sidedness and faultiness are avoided.

Thinking unanimously with oneself at all times – thinking and judging then also result in thinking Thinking must have sufficient breadth and depth to also exist in one’s own attitude or action. This is probably why Hannah Arendt extended these three maxims with the concept of “reflective judgement”. Pointilistically, thoughts on six themes of the cantata “What shall I make of thee, Ephraim?” are to be offered to the reflective judgement of the reader in the following.

Sin

Let us begin with sin. In the text of the cantata, it is paid for with “drops of blood”. In religious education we were taught that God always sees and knows everything. So we’d better not sin at all; but what is always meant is: “in thought, word and deed” – it comes out anyway. The sickening somatisation of this perfidious clerical sin-guilt construction naturally goes from the abdomen to under the skullcap and is still responsible for some hefty health insurance premium percentages today.

One thing we know very well in view of the genius of the brain. It doesn’t give a damn what it may or may not think. We even have to imagine sin so that we can even think that and how we want to avoid it. It is easy to think that the Church wanted to give us instructions on how to do this. In fact, it seems that today everything is allowed that is not explicitly forbidden by law. The self-evident fairness, according to which there is a conscience, simple decency and consideration for one’s fellow human beings, is becoming a dead letter. This is all the more regrettable because our planet is becoming more open, but also more crowded, and this inconsiderateness is being exemplified by the richest countries in particular. As long as this continues, legal regulations will remain necessary. Every person must also demand moderation of his or her own accord. – Is a Franciscan conversion quietly on the horizon?

Mercy

The second theme of the cantata: Mercy. Mercy, the open heart for others, is the quality of tolerance of difference and thus also of acceptance of difference – ultimately of peaceful coexistence (conviviality), as Hans Saner explained in his great essay “Zum Begriff der sozialen Integration” (on the concept of social integration) in 2002 (in: H. S., “Nicht-optimale Strategien”, Essays zur Politik, Lenos Verlag, Basel 2002). In a multicultural world, Saner argues, any expectation of equality of values, religious belief and worldview is illusory and dangerous.

While tolerance is acquiescence and thus degrades the other to the tolerated, tolerance of difference is a necessary but also difficult virtue: tolerance grants, tolerance of difference recognises.

So we too can only be merciful if we also want to know and understand the other. Are we not already very sensitive to difference in our reflexes and also out of convenience – especially in cultural, religious and ideological matters? Reflected difference is and always has been an essential enrichment of every living culture.

The old God – a terminator?

The cantata BWV 89 introduces us to the Old Testament God. He is the third object of this reflection. Somewhat abbreviated, it sounds like this in Hosea: “What shall I make of you, my sinful, apostate people? Shall I protect you, Israel? Shall I not simply destroy you, lay you in ruins like Sodom and Gomorrah? “But no, my heart is of another mind: great is my mercy toward you!”

Hosea lived a good 700 years before the birth of Christ in northern Israel, when the world had less than 200 million inhabitants. Hosea is considered the so-called minor prophet of the Old Testament and is responsible for the text of the cantata. The God who saves the sinful idol-worshipping Israel from destruction out of mercy corresponds – in an exaggerated parallel narrative – to Hosea himself. He had a notoriously unfaithful wife and found himself in the dilemma of whether to cast her out or keep her. Apparently he just couldn’t let go of her.

Is this really “mercy”, this outstanding virtue of all great religions, which means the open, understanding heart: understanding the other, however different he or she may be? Or is Hosea not simply too attached to his obviously desirable wife and unable to part with her?

How does he seem to me, this God of Israel who is locally located in the Old Testament – with all acceptance of the historical connotation? He acts like an unpredictable ruler hovering over the earth in a fully equipped B52 bomber, his fingers on the red button. You can almost hear the ever louder film music to it! It’s the stuff the plots for the James Bond stories are made of! Aren’t all these films plagiarisms of the Old Testament in their own way? It is probably no coincidence that these very popular cinema films mostly come from the workshop of producers of Jewish origin.

But a capricious God who even thinks of punishing collectively and sweepingly can no longer be our God today – whether he has merciful moments or not.

God – somewhat more modern – encompasses everything and thus also nothingness, but also and above all love, children, music and nature. He is perfect and eternal, an all-encompassing inconceivable. That is how one can think about God today.

Jesus – also a doctor

And now to Jesus. Religion and medicine are functional concepts of salvation, yes, promises of salvation – the former with the somewhat uncertain perspective of the eternal, the latter with the certain but also transient perspective of this world. Jesus is the perfect link between the other world and this world: as the Son of God and the Son of Man.

According to my very personal understanding, the historical Jesus was not only a social revolutionary, but also a doctor. In addition to his miraculous healings, his spontaneous empathy and self-sacrificing readiness to act for the suffering, the sick, the marginalised, the hungry and thirsty, as well as criminals, which is still touching today, is extraordinary. He acts like a modern doctor, preventively and socio-politically, like one who saw through and understood the connection between social conditions and healthy free development of life like no other before him.

Jesus wanted to radically change this world. The perspective of the hereafter was rather his formulation of consolation and not of consolation. To the extent that the very vulnerable and transient human being seeks salvation – and in doing so achieves the fantastic, even the almost impossible – the true and realistic hope remains that this world can also be paradise in the sense of the fulfilled promise of a happy, successful life. That is why Jesus cannot be a member of a power-exercising and property-accumulating church.

Man, you can do it!

And then there remains man, that needy cramp before the Lord, so lacking, who struggles to find his way out of misery – and how! But he is also the only one on the planet who can positively change something beyond nature. And we have to build on that. Today, at least in Europe, we live in the safest world there has ever been: soon 70 years without war with many grandiose comforts; moreover, we live longer and healthier than all generations before us.

Man, biblically similar to the image of God, is born incapable of survival, vulnerable and transient: in the cosmic timetable he only shines for a lightning second at a time. He is the eternally curious, tireless inventor and courageous conqueror – Sisyphus and Prometheus at the same time. In the process, he achieves absolutely unheard-of things across all generations: today, Icarus flies with Easyjet, Odysseus tweets with Penelope, Oedipus no longer limps, Hercules sits lonely on his Caterpillar in the Augean stable. The horrors of plague, smallpox, polio, cholera and soon AIDS have faded, the Iron Curtain has fallen. Human rights can be claimed and world hunger, child mortality and illiteracy are finally decreasing worldwide – and this despite a growing world population. And we look curiously into space: the first little scouts are leaving our galaxy.

How would Johann Sebastian Bach work today? He has long since been composing on the computer, no longer needs an army of copiers, but presses the copy-paste button, and, fresh from the laser printer, the scores reach the hands of his musicians. Bach would no longer have to petition the high-born, for the royalties would flow in abundance. He would probably be a filthy rich man and have his entire oeuvre stored on a cloud! You can make it all up!

Paradise

Today we see through it: paradise on earth is not to be found in the South Seas or behind distant eternal clouds, but is tangible, man-made over many generations – and in some places already realised. At least there, where people together dare to create a meaningful life for all and succeed in doing so.

Hunger, poverty, war and lack of education can already be overcome today. In our latitudes, we are experiencing the safest and most comfortable time ever. We are healthier, live longer and are more prosperous than ever before. Awareness of this is still modest, and we grumble at a high level about very, very minor things.

We seem to have forgotten that we are reaping the fruits that generations before us have painstakingly planted and developed, often at the cost of their lives. We easily forget what we owe to future generations with the still unwritten, once self-evident, intergenerational contract.

Isn’t an ensemble of musicians performing incredibly ingenious music of earlier generations, on which the musical geniuses to come build, with instruments and techniques that have evolved over centuries, precisely an exemplary symbol of a creative humanity that has grown in solidarity? Yet the whole is based on all generations and is so much more than just the sum of the achievements of individuals. The especially gifted, the soloists and ensemble leaders, fit into the whole, stand out but do not exalt themselves.

If that is not paradise!

This text has been translated with DeepL (www.deepl.com).