Es reißet euch ein schrecklich Ende

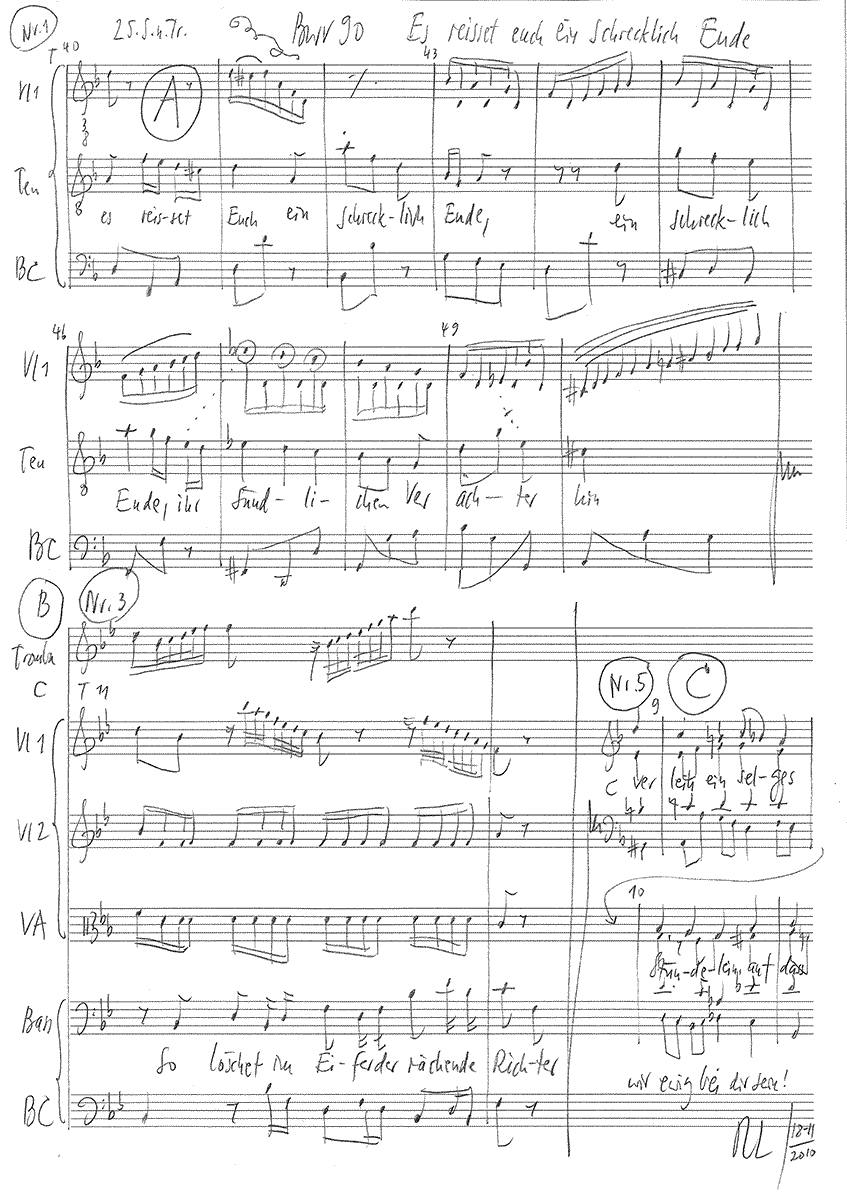

BWV 090 // For the Twenty-fifth Sunday after Trinity

(To ruin you an end of terror) for soprano, alto, tenor and bass, trumpet, strings and continuo

It is said that Bach’s musicians had precious little rehearsal time and often sight-read their performances. If this is true, the shock they must have suffered in the dim light of an autumn morning on 14 November 1725 would have been considerable: for the wild musical flurries that the cantor had written in their parts must have struck not a few with fear of the “terrible end” awaiting not just their mortal souls but also their musical careers. And no doubt many an unsuspecting church-goer would have emerged shaken to the core and desperately regretting their last round of boozing and cards…

Would you like to enjoy our videos ad-free? Subscribe to YouTube Premium now...

Workshop

Reflective lecture

Orchestra

Conductor & cembalo

Rudolf Lutz

Violin

Renate Steinmann, Plamena Nikitassova

Viola

Susanna Hefti

Violoncello

Martin Zeller

Violone

Iris Finkbeiner

Bassoon

Susann Landert

Tromba da tirarsi

Patrick Henrichs

Organ

Norbert Zeilberger

Musical director & conductor

Rudolf Lutz

Workshop

Participants

Karl Graf, Rudolf Lutz

Reflective lecture

Speaker

Rainer Erlinger

Recording & editing

Recording date

11/19/2010

Recording location

Trogen

Sound engineer

Stefan Ritzenthaler

Director

Meinrad Keel

Production manager

Johannes Widmer

Production

GALLUS MEDIA AG, Switzerland

Producer

J.S. Bach Foundation of St. Gallen, Switzerland

Librettist

Text No. 1–4

Poet unknown

Text No. 5

Martin Moller, 1584

Text No. 6

Lazarus Spengler, 1524

First performance

Twenty-fifth Sunday after Trinity,

14 November 1723

In-depth analysis

This is because Bach had found a musical language for the libretto’s end-of-days maledictions that is unrivalled in its radicalism. Opening with a tenor aria “To ruin you an end of terror, Ye blasphemous disdainers, brings”, Bach presents a dark and lashing D minor setting whose interrupted cadences, arpeggios and percussive bass line give neither performer nor audience a moment to breathe: the musical thumbscrews are tightened with relish, and the fermata near the end of the A section seems to rehearse tearing the thread of life, as in a mock execution. Indeed, the music evokes the closing movement of a violin concerto dedicated to the devil, ere the equally agitated middle section reveals the reason for this shocking descent into hell: “Your store of sin is full in measure” – having been offered no sign of repentance, the long-patient judge boils over in a musical fit of rage.

In the following alto recitative, the immense discrepancy between divine goodness and human ingratitude is explored in a strict, dualistic setting. While the vocalists depict the blessings of the Lord in the brightest of colours, the “desp’rate act of mischief” and corruption of humankind are evoked by ear-piercing chords and a forceful interrupted cadence: here goes a sinner who has flaunted probation in eternal, obdurate impenitence! In this dialogue between the offer of mercy and brazen denial, Bach holds a musical sermon of rare intensity that closes with a drastic revocation of the divine promise: “Good deeds are spent on thee for nothing!”

The second aria opens a new scene that is rich in consequences. Whereas the wrathful inquisitor had sought a remorseful confession in the introductory movement, the covenant is now broken and the great judicial drama, with head and hand at stake, commences its deadly course – just as Bach no doubt witnessed more than once in the marketplaces of the cities he worked in. Announced by trumpet fanfares, the court judge enters to preside over the execution of a sentence that bears witness to his power. Aptly set for the bass voice and accompanied by string music of searing implacability, this constellation, transferred to the theological sphere, explodes the boundaries of baroque certitude of faith: how can God as the benevolent father “extinguish the lamp” of his promise and thus revoke the divine covenant? It is clear that the issue is not venial sin but rather a fundamental fall from faith that leads to collective damnation and self-inflicted banishment from the holy sites – a line of argument that, in the context of many of Luther’s late writings, could certainly be called anti-Semitic, had such themes been more than a – thankfully – minor talking point in Bach’s world.

But just as the sinner’s head seems bent to the execution block, the tenor recitative abruptly sets all to rights. It was only a parable and a final warning – God watches steadfastly over his chosen people, whom he will protect from all enemies and indeed from themselves.

The recitative is, however, not followed by a conciliatory movement of musical solace. Rather, the terrified conscience can barely collect itself to issue a subdued closing chorale, one that is to be understood as a plea for God’s blessing in its most comprehensive sense: protection, shelter and comfort here and yon; in this movement, Bach captures the transitory moment of the “blessed hour of peace” with other-worldly grace. The fact that the chorale melody corresponds to the Lutheran “Our Father” hymn reduces all to this unalterable and primary prayer. Seen through the lens of the work’s judicial metaphor, it also calls to mind the last (often sung) words of the condemned at the noose – and thus brings a thoroughly oppressive cantata to its equally disturbing conclusion.

Libretto

1. Arie (Tenor)

Es reißet euch ein schrecklich Ende,

ihr sündlichen Verächter, hin.

Der Sünden Maß ist voll gemessen,

doch euer ganz verstockter Sinn

hat seines Richters ganz vergessen.

2. Rezitativ (Alt)

Des Höchsten Güte wird von Tag zu Tage neu,

der Undank aber sündigt stets auf Gnade.

O, ein verzweifelt böser Schade,

so dich in dein Verderben führt.

Ach! wird dein Herze nicht gerührt?

daß Gottes Güte dich

zur wahren Buße leitet?

Sein treues Herze lässet sich

zu ungezählter Wohltat schauen:

Bald läßt er Tempel auferbauen,

bald wird die Aue zubereitet,

auf die des Wortes Manna fällt,

so dich erhält.

Jedoch, o! Bosheit dieses Lebens,

die Wohltat ist an dir vergebens.

3. Arie (Bass)

So löschet im Eifer der rächende Richter

den Leuchter des Wortes zur Strafe doch aus.

Ihr müsset, o Sünder, durch euer Verschulden

den Greuel an heiliger Stätte erdulden,

ihr machet aus Tempeln ein mörderisch Haus.

4. Rezitativ (Tenor)

Doch Gottes Auge sieht auf uns als Auserwählte:

Und wenn kein Mensch der Feinde Menge zählte,

so schützt uns doch der Held in Israel,

es hemmt sein Arm der Feinde Lauf

und hilft uns auf;

des Wortes Kraft wird in Gefahr

um so viel mehr erkannt und offenbar.

5. Choral

Leit uns mit deiner rechten Hand

und segne unser Stadt und Land;

gib uns allzeit dein heilges Wort,

behüt fürs Teufels List und Mord;

verleih ein selges Stündelein,

auf daß wir ewig bei dir sein!

Rainer Erlinger

“Retribution, Prevention and Formation of Conscience”.

Of the warning, avenging, punishing, loving, inner, internalised and final judge.

“It tears you a terrible end”. One must admit, there are more pleasing titles of Bach cantatas. A glance at the list of cantatas performed this year by the Bach Foundation in Trogen alone confirms this: “Wie schön leuchtet der Morgenstern”, “Erwünschtes Freudenlicht” and even next year: “Ich bin vergnügt mit meinem Glücke”, “Erfreut euch, ihr Herzen”.

What is hidden behind the cantata title “Es reisset euch ein schrecklich Ende”? A prophecy, a prognosis, a threat, a warning? From the wording, it could indeed be a prognosis: a prediction for a future event, derived from given initial conditions and framework conditions. If this is so, however, one must unfortunately conclude: Not a good prognosis, a medical doctor would probably call it “infaust”.

But it could also be a warning. Something is to be warned about so that it can be avoided. Those addressed are still in a position to avert fate. They can turn the wheel and head for a new destination, here, in the cantata, a destination to which they are guided by God’s goodness: true repentance. We will come back to this later.

But first, the main character of this cantata. Who is she? The listener, that is, us? Probably not. We, the listeners, are addressed, we are threatened by fate, we are “sinful despisers” who are threatened by the “terrible end”. The real protagonist seems to me to be the judge who appears in the two arias: the judge of the Last Judgement – or at least the judge of the particular judgement after individual death – i.e. God.

However, one could also doubt this if one were to draw up something like character profiles across the entire cantata. For the judge from the arias is harsh and merciless. Having forgotten him, the sinner comes to a terrible end in the first aria:

“It snatches a terrible end from you,

you sinful despisers.

The measure of your sins is full;

But your very hardened mind

hath wholly forgotten his judge.”

And he is an avenging judge, who in the second aria, in the zeal of punishment, extinguishes the lampstand of the word for punishment after all, even brings about abominations.

“So in zeal the avenging judge extinguishes

the lampstand of the word of punishment.

You must, O sinners, through your fault

suffer the abomination in the holy place,

you make temples a murderous house.”

However, whenever “God” or the “Most High” is explicitly mentioned, we hear of something else, almost the opposite. Thus in the first recitative:

“The goodness of the Most High is renewed from day to day,

(…)”

or:

“(…),

alas! Is not thy heart stirred?

That God’s goodness

Lead thee to true repentance? (…)”

and in the second recitative:

“But God’s eye is upon us as the chosen ones.

(…),

His arm restrains the course of our enemies…

and helps us up,

(…)”

Indeed, the impression is given here that we are dealing with two different persons. But it is probably the same God, who only has two different sides: a strict and a forgiving one. Perhaps it is the strict God of the Old Testament and the loving one of the New? But one also thinks of the principle of “carrot and stick”. Therefore, the question arises: What does this judge want? What does he want to achieve with his punishment?

For earthly judges, criminal jurisprudence distinguishes three goals in the purpose of punishment: Retribution, general prevention and special prevention.

We know retribution from the Old Testament: an eye for an eye, a tooth for a tooth. Immanuel Kant also advocated this approach:

“But if he has murdered, he must die. There is no surrogate here for the satisfaction of justice. (…) – Even if bourgeois society were to dissolve with all its members united (e. g. (e.g. the people inhabiting an island decided to disperse and scatter all over the world), the last murderer in prison would have to be executed beforehand, so that everyone would receive what his deeds are worth, and the guilt of blood would not adhere to the people who did not insist on this punishment: because they can be regarded as participants in this public violation of justice”.

Hegel understood punishment as the negation of the negation of right. He conceived of crime as the negation of right, and punishment thus as the “negation of this negation”, as the “annulment of the crime that would otherwise apply”, and thus as the restoration of right. In paragraph 101 of the “Basic Lines of the Philosophy of Right”, Hegel literally writes: “The abolition of the crime is in so far as it is, according to the concept, violation of the violation, Wiedervergeltung.”

At this point, however, the question arises as to how one can compensate for or annul an evil, the crime or here the sin, by adding another evil, the punishment, here the “tearing of the terrible end”. Does this not in fact only increase or double the evil, and conversely make everything worse?

The question brings to mind a sentence by the Roman philosopher Seneca, which is central to considerations of the purpose of punishment:

“Nam, ut Plato ait: nemo prudens punit, quia peccatum est, sed ne peccetur.” – (For, as Plato says, no prudent man punishes because sin has been committed, but that sin may not be committed).

The passage in Plato to which Seneca refers reads: “But this chastisement does not befall him because of the evil inflicted – after all, what has happened cannot be undone – but so that for the time to come he himself and those who see him punished may either detest injustice altogether, or so that such evil may be lessened in many ways.

With this, Plato has already recognised and distinguished the two different mechanisms that come into play. Punishment is intended to deter further crimes: Prevention. If the specific offender himself is to be deterred from committing further crimes, then it is called special prevention. He is to be reintegrated into the society of the law-abiding, in other words, resocialised. Plato, however, names not only the offender but also “those who see him punished” as the addressees of punishment. They, too, are to learn to detest what is unjust, and thus mischief is to be prevented. Since prevention here is directed at everyone, it is called general prevention.

Now what does the judge of the cantata want to achieve in the person addressed in the cantata? Is absolute justice to be achieved? Is the injustice to be righted by draconian retributive punishments threatened by the zealously avenging judge? Only, then, why the kindness and mercy? It points to something else. Man is to be guided to the better. That is why he is addressed and admonished in the cantata. This indicates that it is at least also about prevention. However, there is a problem here: it is probably a bit late for resocialisation at the Last Judgement. So it can either only be about a general preventive effect, about general prevention. Or we hear – and this brings me back to the beginning – the warning of the cantata, so that we turn back in time before it is too late. The warning of the punishment, the prophecy of what will happen, is meant to have an effect even before the punishment is imposed in the Last Judgement. Or – as a third possibility – the judge must act before the Last Judgement. We also know another judge than the judge of the Last Judgement: the inner judge.

This image was brought up by the Apostle Paul when he wrote in the Letter to the Romans about thoughts accusing and defending one another before one instance, that is, before one judge: the conscience (Romans 2:14,15):

“For if Gentiles, who do not have the law, nevertheless do by nature what the law requires, they, though they do not have the law, are law to themselves. They prove thereby that what the law requires is written in their hearts, especially as their consciences testify to it, in addition to the thoughts that accuse or also excuse one another.”

Immanuel Kant took this up for his definition of conscience:

“The consciousness of an inner court in man (before which his thoughts accuse or excuse one another) is conscience.

Every human being has a conscience and finds himself observed, threatened and generally held in respect by an inner judge, and this power that watches over the laws in him is not something that he makes for himself (arbitrarily), but is incorporated into his being. It follows him like his shadow when he intends to escape. He can indeed stupefy himself through pleasures and distractions or put himself to sleep, but he cannot avoid coming to himself now and then or waking up, where he immediately hears the terrible voice of it. In his extreme depravity he can at most bring himself not to turn to it at all, but he cannot avoid hearing it.”

But how does this inner judge get there, inside? Kant again on this:

“Just so, conscience is not something acquired, and there is no duty to acquire one; but every man, as a moral being, has such a thing originally in himself.”

From this follows for dealing with conscience:

“The duty here is only to cultivate one’s conscience, to sharpen one’s attention to the voice of the inner judge, and to use all means (hence only indirect duty) to make it heard.”

The inner judge is therefore inherent in each of us and we only have to make him heard. This could be the task of the cantata, the meaning of the warning: it should make the sinner listen to the inner judge.

But there is also another theory of how this inner judge came into us: that of Sigmund Freud. Freud – unlike Kant – denied the existence of an original, nature-given capacity for discerning good and evil and developed his own theory. According to him, this ability to distinguish comes about through foreign influence. At first, man learns this distinction from outside, from his parents, and follows it out of fear of losing the love of his parents if he behaves wrongly:

“In this, then, foreign influence shows itself; this determines what is to be called good and evil. Since man’s own feelings would not have led him along the same path, he must have a motive for submitting to this foreign influence. It is easily discovered in his helplessness and dependence on others, and can best be described as fear of losing love. If he loses the love of the other on whom he is dependent, he also loses the protection against many dangers, exposes himself above all to the danger that this superior will prove his superiority to him in the form of punishment. Evil, then, is initially that for which one is threatened with loss of love; out of fear of this loss one must avoid it.”

Against this background, anyone who lets the cantata text sink in again will be amazed. For love and the withdrawal of love, that is precisely the contrast between the loving God in the recitatives and the punishing judge in the arias. The extinguishing of the “lamp of the word” in the second aria can very well be read as a threatened turning away of God, as a withdrawal of love.

And protection from danger is also explicitly mentioned:

“(…),

the hero in Israel protects us,

His arm restrains the course of our enemies…

and helps us up,

(…)”

But according to Freud, it does not remain in this situation. He continues:

“One calls this state ‘bad conscience’, but actually it does not deserve this name, for at this stage the consciousness of guilt is evidently only fear of losing love, (…) ‘social fear’.(…) A great change occurs only when authority is internalised by the erection of a super-ego. This raises the phenomena of conscience to a new level; in fact, it is only now that one should speak of conscience and guilt.”

According to Freud, then, conscience, the inner judge, is nothing other than the internalised authority of the parents. Transferred to the cantata, it would be that of the heavenly Father. Freud, by the way, did see these parallels between parents and God. He even explicitly points out that religion offers a providence for life alongside an explanation for the riddles of the world:

“This providence the common man cannot imagine otherwise than in the person of a grandly exalted Father. Only such a one can know the needs of the human child, be softened by his pleas, be appeased by the signs of his repentance.”

With this information, if we now turn back to the cantata text, something very astonishing stands out: Between the second aria and the second recitative, the person changes. Until the end of the second aria, the listeners are addressed in the second person. From “Es reisset Euch ein schrecklich Ende” to “ihr machet aus Tempel ein mörderisch Haus”. But then suddenly it continues in the first person: “But God’s eye looks upon us as the chosen ones” and this is maintained until the end of the chorale: “that we may be with you forever!”

Inevitably, the internalisation of the warnings from the first part of the cantata comes to mind. The external authority of the divine Father, before whose withdrawal of love the sinner fears, becomes the internal authority of the inner judge, the conscience, which can then also take action on an ongoing basis, even before the Last Judgement. Thus the cantata text seems compatible with both models, on the one hand with the idea that the listeners are warned to give more voice to the inner judge in Kant’s sense, who is there from the beginning. The cantata is then, to a certain extent, a voice coming from outside – as beautiful as it is insistent – which supports the voice of the inner judge. On the other hand, the cantata text is also compatible with the idea that the forcefulness of the warning, combined with the fear of being deprived of love in the sense of Freud, leads the listeners to internalise the guidelines of the supreme father, to let them become the superego and thus to feel them as the voice of their own conscience.

Literature

– Sigmund Freud, The Discomfort in Culture, Reclam Verlag, Stuttgart 2010

– Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel, Basic Lines of the Philosophy of Right, ed. by Helmut Reichelt, Frankfurt a. M. 1972

– Immanuel Kant, The Metaphysics of Morals, Kant’s Werke Volume VI, Berlin 1914

– Plato, Nomoi, 934a, translated by Hieronymus Müller, Sämtliche Werke, Volume 4, Rowohlt Verlag, Reinbek 1994

This text has been translated with DeepL (www.deepl.com).