Wer Dank opfert, der preiset mich

BWV 017 // For the Fourteenth Sunday after Trinity

(Who thanks giveth, he praiseth me) for soprano, alto, tenor and bass, vocal ensemble, oboe I+II, strings and basso continuo

Would you like to enjoy our videos ad-free? Subscribe to YouTube Premium now...

Workshop

Reflective lecture

Choir

Soprano

Jessica Jans, Simone Schwark, Susanne Seitter, Alexa Vogel, Anna Walker, Mirjam Wernli

Alto

Jan Börner, Antonia Frey, Liliana Lafranchi, Lea Pfister-Scherer, Lisa Weiss

Tenor

Marcel Fässler, Zacharie Fogal, Manuel Gerber, Joël Morand

Bass

Johannes Hills, Grégoire May, Daniel Pérez, Philippe Rayot, Tobias Wicky

Orchestra

Conductor

Rudolf Lutz

Violin

Eva Borhi, Lenka Torgersen, Christine Baumann, Petra Melicharek, Dorothee Mühleisen, Ildikó Sajgó

Viola

Peter Barczi, Sonoko Asabuki, Nadine Henrichs

Violoncello

Maya Amrein, Daniel Rosin

Violone

Shuko Sugama

Oboe

Philipp Wagner, Katharina Arfken

Bassoon

Gilat Rotkop

Harpsichord

Thomas Leininger

Organ

Nicola Cumer

Musical director & conductor

Rudolf Lutz

Workshop

Presenters

Rudolf Lutz, Pfr. Niklaus Peter

Reflective lecture

Speaker

Vanessa Wood

Recording & editing

Recording date

20.09.2019

Recording location

Teufen AR (Schweiz) // Evangelische Kirche

Sound engineer

Stefan Ritzenthaler, Nikolaus Matthes

Producer

Meinrad Keel

Production manager

Johannes Widmer

Production

GALLUS MEDIA AG, Schweiz

Producer

J.S. Bach-Stiftung, St. Gallen (Schweiz)

Librettist

First performance

22 September 1726, Leipzig

Librettist

Psalm 50, 23 (movement 1); Luke 17:15–16 (movement 4); Johann Gramann (movement 7); unknown poet (perhpas Herzog Ernst Ludwig v. Sachsen-Meiningen: movements 2, 3, 5, 6)

In-depth analysis

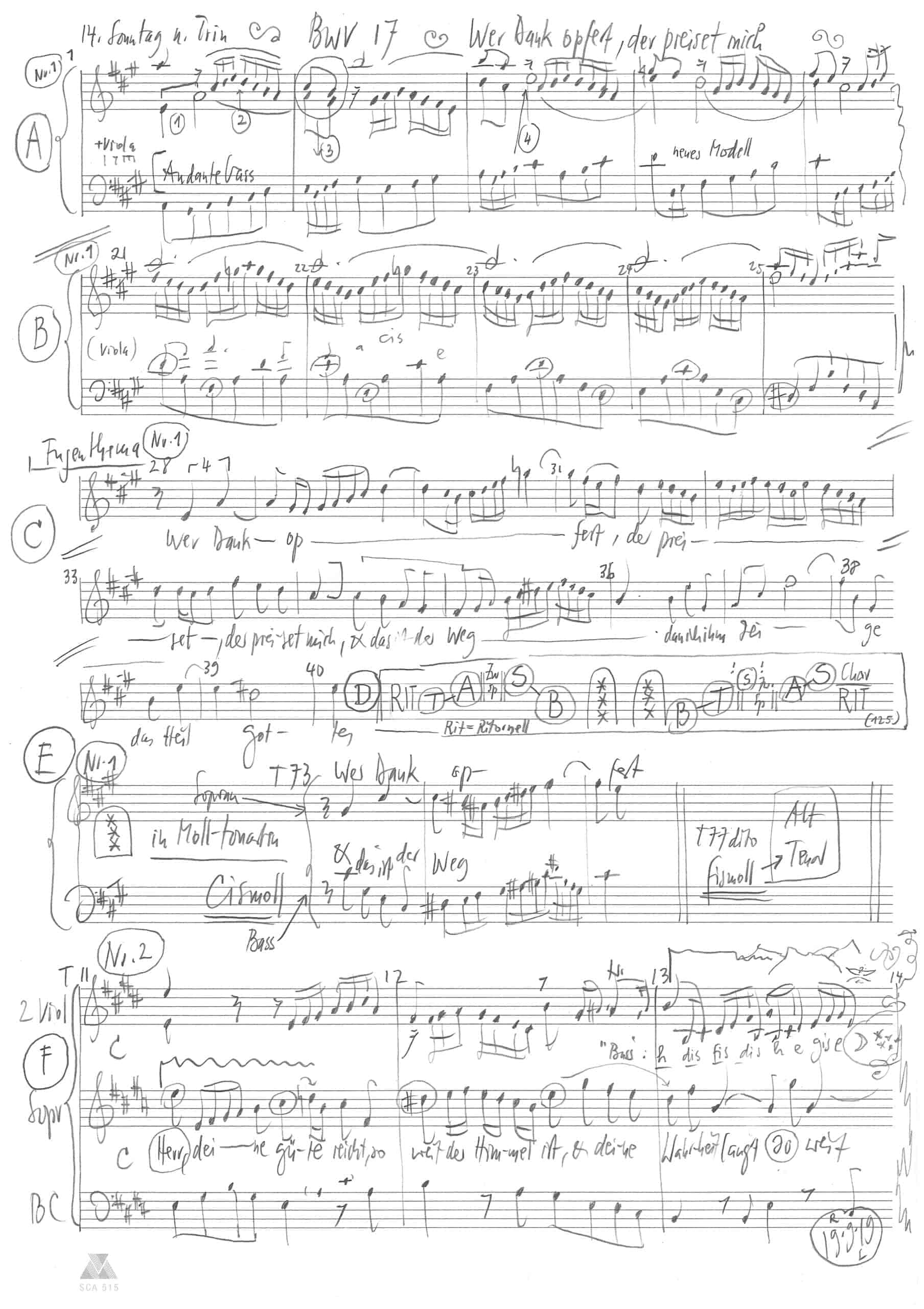

Cantata BWV 17 “Wer Dank opfert, der preiset mich” (Who thanks giveth, he praiseth me) also belongs to the two-part “Meiningen-style cantatas” that Bach composed in 1726. In contrast, however, to his otherwise rather sombre and melancholic compositions for the Fourteenth Sunday after Trinity (BWV 25 and 78), the theological focus of BWV 17 lies on the sacrifice of praise owed to God for his healing and comfort and thus embraces a music of brighter tones.

Set in the clear key of A major, the introductory chorus opens with an instrumental setting of interweaving oboe and violin parts over a quaver continuo line, ere a motet style emerges with the fugue-like entries of the choral voices. As the movement progresses, free counterpoint and brief interludes meld to realise a complete setting, whose unhurried length transforms a lifelong obligation to offer thanks (taken from Psalm 50) into an inviting prospect.

“Luft, Wasser, Firmament und Erden” (air, water, firmament and earth) – in the alto recitative, the whole of creation is called upon to witness God’s majesty. Through its balance of descriptive declamation and consoling contemplation, the movement aptly sets the stage for the touching vibrance of the soprano aria, “Herr, deine Güte reicht, so weit der Himmel ist” (Lord, thy goodwill extends as far as heaven is), a hymnic, inspiring text that no doubt would have captivated every baroque composer. And Bach was no exception. His setting, in a radiant E major key, indeed showcases both his skill and unique style: the entry of the soloist is preceded by an intense trio setting for two violins and continuo, which, when joined by the thematically equal soprano melody, evolves into a full quartet – the compositional form that in Telemann’s opinion constituted the true “touchstone” of musical art.

True to form, the second part of the cantata opens with a passage from the New Testament: the gospel on cleansing ten lepers. With exceptional artistry, Bach transforms this tenor recitative into a dramatic short story culminating in the exemplary expression of thanks offered by just one among the cured, a Samaritan – and it indeed seems to be that particular soul, ready to receive mercy, who, in the ensuing tenor aria, extols the wealth of favours bestowed. Featuring long echoing passages and a merrily circling bass figure, the dance-like movement is set in three sections in line with the form of the text. Because the head motive is unusually catchy, Bach scholar Hans-Joachim Schulze suggested it may stem from an – as yet undiscovered – popular folk tune; beneath the humble folkloric style there is certainly no shortage of musical confidence. Given the context of singing praises of thanks, perhaps no further explanation is required.

The themes of accepting the limits of human possibility and appreciating the liberating presence of mercy are further addressed in the bass recitative, a setting that interprets the healing mentioned in the gospel as a promise of future splendour. In contrast, the closing chorale “Wie sich ein Vatr erbarmet” (As hath a father mercy), is less a triumphant conclusion than a prayer pervaded by the burdens of life and premonitions of death; its text, the third stanza of the hymn “Nun lob, mein Seel, den Herren” (Johann Gramann, 1530), composed in 12-line stanzas, is of unusual length. In this recording, we have interspersed organ interludes throughout the setting – a delicate undertaking that can be understood as a reference to Bach’s introspective double-chorus treatment of the same text in the middle movement of the motet “Singet dem Herrn” BWV 225.

Libretto

1. Chor

Wer Dank opfert, der preiset mich,

und das ist der Weg,

daß ich ihm zeige das Heil Gottes.

2. Rezitativ — Alt

Es muß die ganze Welt ein stummer Zeuge

werden von Gottes hoher Majestät,

Luft, Wasser, Firmament und Erden,

wenn ihre Ordnung als in Schnuren geht;

ihn preiset die Natur mit ungezählten Gaben,

die er ihr in den Schoß gelegt,

und was den Odem hegt,

will noch mehr Anteil an ihm haben,

wenn es zu seinem Ruhm so Zung

als Fittich regt.

3. Arie — Sopran

Herr, deine Güte reicht,

so weit der Himmel ist,

und deine Wahrheit langt,

so weit die Wolken gehen.

Wüßt ich gleich sonsten nicht,

wie herrlich groß du bist,

so könnt ich es gar leicht

aus deinen Werken sehen.

Wie sollt man dich mit Dank davor

nicht stetig preisen?

Da du uns willt den Weg des Heils

hingegen weisen.

4. Rezitativ — Tenor

Einer aber unter ihnen, da er sahe,

daß er gesund worden war,

kehrete um und preisete Gott

mit lauter Stimme und fiel auf sein

Angesicht zu seinen Füßen und dankete ihm,

und das war ein Samariter.

5. Arie — Tenor

Welch Übermaß der Güte

schenkst du mir!

Doch was gibt mein Gemüte

dir dafür?

Herr, ich weiß sonst nichts zu bringen,

als dir Dank und Lob zu singen.

6. Rezitativ — Bass

Sieh meinen Willen an, ich kenne, was ich bin:

Leib, Leben und Verstand, Gesundheit, Kraft und Sinn,

der du mich läßt mit frohem Mund genießen,

sind Ströme deiner Gnad,

die du auf mich läßt fließen.

Lieb, Fried, Gerechtigkeit

und Freud in deinem Geist sind Schätz,

dadurch du mir schon hier ein Vorbild weist,

was Gutes du gedenkst mir dorten zuzuteilen

und mich an Leib und Seel vollkommentlich

zu heilen.

7. Choral

Wie sich ein Vatr erbarmet

übr seine junge Kindlein klein:

So tut der Herr uns Armen,

so wir ihn kindlich fürchten rein.

Er kennt das arme Gemächte,

Gott weiß, wir sind nur Staub.

Gleich wie das Gras vom Rechen,

ein Blum und fallendes Laub,

der Wind nur drüber wehet,

so ist es nimmer da:

also der Mensch vergehet,

sein End, das ist ihm nah.

Vanessa Wood

Ladies and gentlemen, esteemed audience, good evening.

What beautiful music.

We sit in this church with its acoustics and spiritual environment, and we experience music that resonates in our souls and awakens in us a range of human emotions.

We rejoice in the solemn fugue, we are drawn into a contemplative state with the tenor’s recitative, and we feel a humility in the quiet, concluding chorale.

This music awakens emotions in us, and at the same time it follows strict rules, the rules of counterpoint. Bach was its undisputed master, virtuoso in the handling of musical combinatorics.

Within the musical passage, therefore, a dialectic presents itself. We have well-defined structures that evoke what we often understand as the opposite of structures – emotions.

The text of the cantata itself also invites us to embrace the opposition of structure and emotion. The cantata points out the majestic order of the world and reminds us that in recognising its beauty, the greatness of God is revealed. The cantata also describes our fragility and our lack of understanding of the greater order. We are challenged to reflect on an all-encompassing structure and a heavenly plan, greater than ourselves.

As a scientist and engineer whose research focuses on how structures of materials as small as atoms can be controlled to the macro level, I am fascinated by structure and how we humans interact with it.

This is a topic I would like to explore with you this evening: How do structure and emotion relate to each other?

This question has preoccupied humanists and scientists since ancient times. Pythagoras explored whether the movement of celestial bodies corresponds to consonant intervals. And later Plato asked: Can music control emotions? Chinese philosophers pondered: can music explain the harmony between people, their leaders, and the cosmos?

Let us first reflect on structure. A basic principle of structure – in music or elsewhere – is that it can be described mathematically.

For musicologists interested in the mathematical structure of music, Bach is dream territory. In 1923, the Swiss-German composer Wolfgang Graeser wrote in his treatise on Bach’s The Art of Fugue: “The property of symmetry plays such a tremendous role in music that it deserves to be considered first.”

In mathematics and the natural sciences, we describe the symmetry of a structure through group theory, a discipline of algebra that describes how objects are related to each other in a group. In 1926, the Swiss mathematician and philosopher Andreas Spieser used certain concepts of group theory to explain how, in a Bach fugue, the theme is changed and developed in several voices: by being used at different pitches, reversed, accelerated, slowed down and mirrored.

Mathematicians call these changes permutations.

The permutations of group theory are also the basis of modern cryptography, which you use to connect to online banking or when exchanging WhatsApp messages. Is music then a kind of code?

The clearly defined framework of mathematical symmetry allows for enormous diversity: in the world of tones as well as in the world of atoms. Like tones in music, atoms are the building blocks of all materials.

In solids, there are only 230 different arrangements between atoms, so-called symmetry groups. If we combine the atoms of the 118 elements in the periodic table with the 230 symmetry groups, we get the diversity we experience in the world around us.

A single note played with two different rhythmic arrangements creates two unique musical phrases. Similarly, one element in the periodic table in two different symmetrical arrangements results in two completely different materials.

Carbon atoms in the arrangement of symmetry group 186 form graphite, the black conductive material used in industrial lubricants. The same carbon atoms in the arrangement of symmetry group 227 form diamond, that clear, hard jewel.

The unique properties of these materials come from the specific rotational, mirror and inversion symmetries in which the atoms are arranged. So in my research we use the same words that a musicologist uses to describe the elements of counterpoint in Bach.

Another branch of mathematics, topology, allows us to describe the complexity of a structure. In music, the descriptors of topology are used to describe the different harmonies and the complex interplay of voices. In doing so, it is the same mathematical descriptors that allow us to design our communication and power networks to improve reliability, redundancy and speed.

We use the concepts of topology to describe the connectivity and mechanical structure of tissues and bones in the human body to design artificial material for prostheses. We also use topology to describe the complex pathway in which lithium ions move in batteries, or to describe the pores in rock layers to figure out how to extract oil or gas most efficiently.

This picture of the world, where we can apply mathematical descriptors to anything, may seem unsettling, like the futuristic imaginary land in Hermann Hesse’s Glass Bead Game, where scientists participate in a complex game to develop mathematical rules to fully describe the arts and sciences.

Our ability to describe the structure of music mathematically leads to the question: Can we reconstruct Bach with the help of mathematics?

I would like to try to answer this question with an example. A popular exercise in a lecture on music theory is to compose a fugue or chorale in the manner of Bach. One of the challenges in such an exercise is to use the rules of counterpoint correctly. At my alma mater, MIT, harmony and counterpoint is offered as a minor. The engineering students there, whose forte tends to be writing code and algorithms, quickly realise that the easiest and safest way for them to get a good grade is not by writing their own composition, but by writing a computer programme that generates music according to the rules of counterpoint. The melody may not seem inspiring, but it strictly adheres to the rules of counterpoint.

Machine learning allows us to teach computers to make static decisions that are structurally similar to the decisions Bach used in his music. One project, better known as Bach Bots, reads Bach chorales into computers. The computer learns the form and composes Bach-style chorales on it. The amazing thing is that untrained ears cannot reliably distinguish between the computer-generated music and Bach’s original chorales. Listeners who are familiar with Bach – and that probably includes all of you – recognise the author in 70% of cases, however.

This means that we can use computers to generate structurally “perfect” counterpoints and use machine learning algorithms to teach computers to compose like Bach. The fact that these computer-generated compositions don’t sound terrible is a good indication that there is something inherent in the structures of counterpoint that evokes emotion.

We asked ourselves before: is music a kind of code? Would this code be a cryptographic key to unlock emotions?

Perhaps this is what Leibnitz, the 17th century mathematician, philosopher and musician, meant when he wrote: “Music is the hidden arithmetical activity of the soul, which is not aware that it is calculating.”

How does our soul perform this calculation?

Brain studies show a clear electrophysiological response to consonance, which is the basis of counterpoint, but we cannot yet explain the individual arithmetical operations; the human soul resists simple mathematical formulae.

Bach played on a digital synthesiser is still Bach. The structural elements are there, but our emotional response to the digital version is very different compared to the live performance including voice and instruments as we hear it today. We connect in this church with the smiles on the musicians’ faces, the way they look at each other and the audience. The joy of playing and singing Bach’s music, unique to each performance, cannot be expressed with a mathematical formula.

With this in mind, as we are allowed to hear the cantata again, let us be in awe of the brilliant mathematical construct that forms the basis of this music and the structure of the world around us. Let us also recognise our emotions that Bach’s musical genius evokes in us – fragility, security, gratitude, wonder – and that connect us to his music.

This text has been translated with DeepL (www.deepl.com).