Das neugeborne Kindelein

BWV 122 // Sunday after Christmas

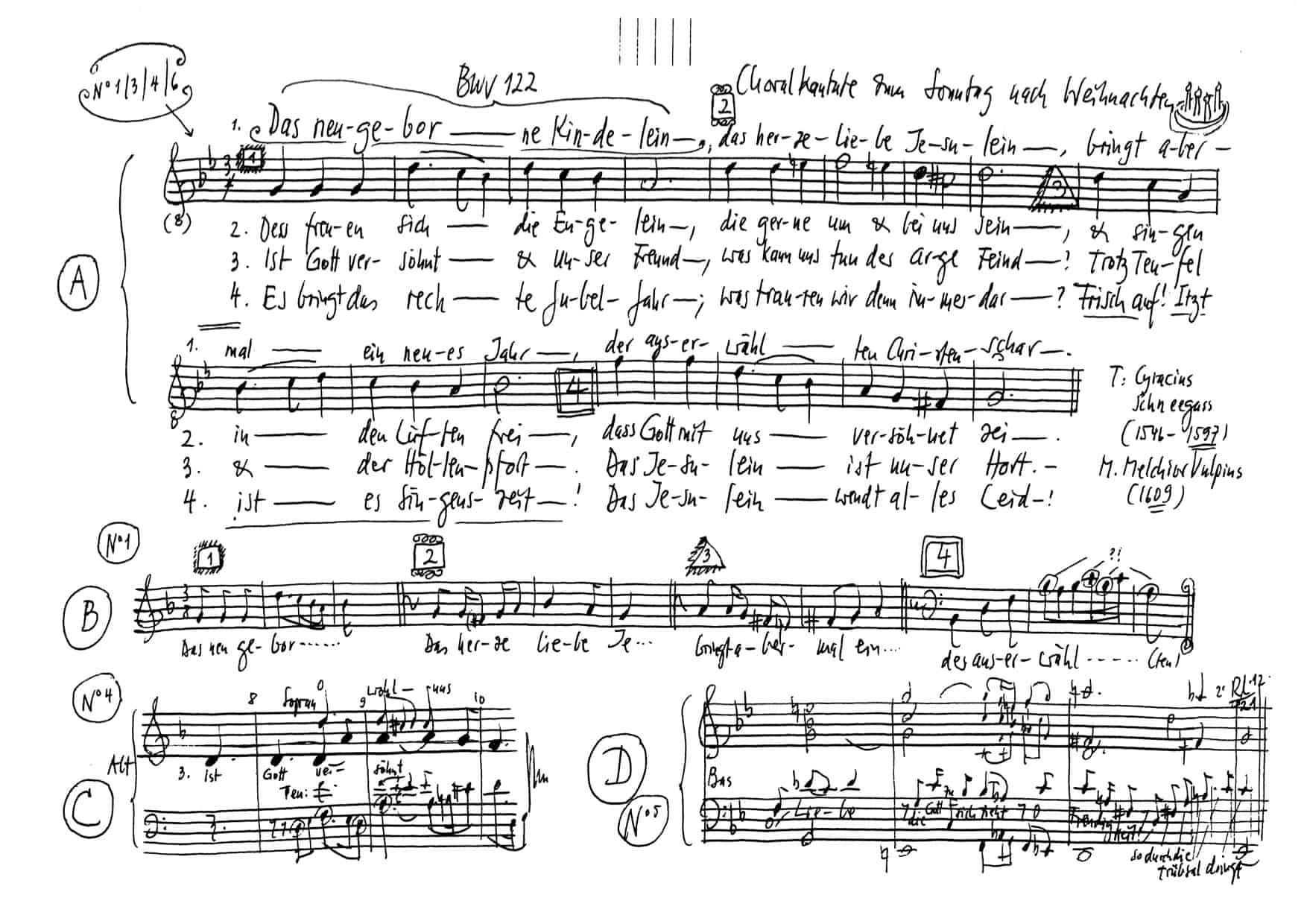

(The newly born, the tiny childment they will cast you) for soprano, alto, tenor and bass; vocal ensemble, recorder I-III, oboe I+II, taille, strings and basso continuo

Place of composition in the church year

Pericopes for Sunday

Pericopes are the biblical readings for each Sunday and feast day of the liturgical year, for which J. S. Bach composed cantatas. More information on pericopes. Further information on lectionaries.

Lobet den Herrn, alle Heiden; preiset ihn, alle Völker! Denn seine Gnade und Wahrheit waltet über uns in Ewigkeit. Halleluja!

Ich sage aber: Solange der Erbe unmündig ist, so ist zwischen ihm und einem Knechte kein Unterschied, ob er wohl ein Herr ist aller Güter; sondern er ist unter den Vormündern und Pflegern bis auf die Zeit, die der Vater bestimmt hat. Also auch wir, da wir unmündig waren, waren wir gefangen unter den äusserlichen Satzungen. Da aber die Zeit erfüllet ward, sandte Gott seinen Sohn, geboren von einem Weibe und unter das Gesetz getan, auf dass er die, so unter dem Gesetz waren, erlöste, dass wir die Kindschaft empfingen.

Und sein Vater und seine Mutter verwunderten sich des, das von ihm geredet ward. Und Simeon segnete sie und sprach zu Maria, seiner Mutter: «Siehe, dieser wird gesetzt zu einem Fall und Auferstehen 57 vieler in Israel und zu einem Zeichen, dem widersprochen wird (und es wird ein Schwert durch deine Seele dringen), auf dass vieler Herzen Gedanken offenbar werden.» Und es war eine Prophetin, Hanna, eine Tochter Phanuels, vom Geschlecht Asser; die war wohl betagt und hatte gelebt sieben Jahre mit ihrem Manne nach ihrer Jungfrauschaft und war nun eine Witwe bei vierundachtzig Jahren; die kam nimmer vom Tempel, diente Gott mit Fasten und Beten Tag und Nacht. Die trat auch hinzu zu derselben Stunde und pries den Herrn und redete von ihm zu allen, die da auf die Erlösung zu Jerusalem warteten. Und da sie es alles vollendet hatten nach dem Gesetz des Herrn, kehrten sie wieder nach Galiläa zu ihrer Stadt Nazareth. Aber das Kind wuchs und ward stark im Geist, voller Weisheit, und Gottes Gnade war bei ihm.

Would you like to enjoy our videos ad-free? Subscribe to YouTube Premium now...

Workshop

Reflective lecture

Bonus material

Publikationen zum Werk im Shop

Choir

Soprano

Linda Loosli, Jennifer Rudin, Susanne Seitter, Baiba Urka, Alexa Vogel, Maria Deger

Alto

Laura Binggeli, Antonia Frey, Lea Pfister-Scherer, Jan Thomer, Lisa Weiss

Tenor

Marcel Fässler, Raphael Höhn, Klemens Mölkner, Tiago Oliveira

Bass

Jean-Christophe Groffe, Fabrice Hayoz, Johannes Hill, Philippe Rayot, William Wood

Orchestra

Conductor & Harpsichord

Rudolf Lutz

Violin

Renate Steinmann, Monika Baer, Andrea Brunner, Ildikó Sajgó, Olivia Schenkel, Salome Zimmermann

Viola

Susanna Hefti, Matthias Jäggi, Claire Foltzer

Violoncello

Martin Zeller, Hristo Kouzmanov

Violone

Markus Bernhard

Recorder

Annina Stahlberger, Teresa Hackel, Amy Power

Oboe

Amy Power, Ana Ines Feola

Taille

Ingo Müller

Bassoon

Susann Landert

Organ

Nicola Cumer

Musical director & conductor

Rudolf Lutz

Workshop

Participants

Rudolf Lutz, Pfr. Niklaus Peter

Reflective lecture

Speaker

Daniel Johannsen

Recording & editing

Recording date

17/12/2021

Recording location

St. Gallen (Switzerland) // Olma-Halle 2.0

Sound engineer

Stefan Ritzenthaler

Producer

Meinrad Keel

Executive producer

Johannes Widmer

Production

GALLUS MEDIA AG, Schweiz

Producer

J.S. Bach-Stiftung, St. Gallen, Schweiz

Librettist

First performance

31 December 1724, Leipzig

Text

Cyriakus Schneegass (movements 1, 4, 6), unknown source (movements 2, 3, 5)

In-depth analysis

For his chorale cantata cycle of 1724/25, Bach employed hymn material stemming from various poets and epochs, integrating these works week for week into cantatas ranging in compositional approach from archaic motets to modern orchestral settings. In BWV 122, the brief, four-line verses from Cyriakus Schneegass’s 1597 hymn are interwoven throughout the setting, creating a bridge between the joy of Christmas and the hopes for a blessed New Year – a sentiment that fits well with our modern celebration of the turn of the year.

In the introductory chorus, the vocal writing combines compact efficiency with a subtle treatment of the pre-imitations, lending the cantus firmus in the high soprano register particular effect. A bittersweet tension emerges between the lilting 3⁄ 8 -metre and muted G-minor tonality, capturing the bliss of Jesus’ birth while also embodying his coming farewell and thus linking the introspective echo effects of the strings and oboes with the semantic import of the piece.

The following bass aria opens with an expansive continuo ritornello, whose probing sequences and arduous leaps lend musical form to the oft-futile struggle against sin and weakness, ere the soloist issues his explicit admonishment. All the same, we evidently require only a small shift in perspective to discover the presence of comforting angels behind the earnest life so masterfully depicted by Bach – and to actively seek their company.

In the soprano recitative, it becomes clear that these angels are not grim harbingers of the apocalypse but benevolent messengers of the annunciation, even a part of the church community. Instead of offering a harmonic accompagnato, the three obbligato voices supporting the soprano present the main chorale of the cantata. That Bach, perhaps in the last moment, decided to assign these parts to three recorders and not to the powerful orchestra enhances the Christmas references of the cantata and transports the angels, and with them the listeners, back to the heart-warming scene of the nativity.

In the fourth movement, an aria, Bach presents an unusual solution to the problem posed by the libretto: namely, how to link the freely texted words of thanks with the hymn verse “Ist Gott versöhnt und unser Freund” (If God, appeased, is now our friend). Rather than choosing the more common device of interpolation to alternate between the two levels, Bach opts for a simultaneous presentation of the texts that groups the soprano and tenor around the pillar of the cantus firmus, which is assigned to the alto. This movement, too, opens with a flowing continuo ritornello, followed by a spirited presentation of the hymn reinforced by strings and the enraptured vocal coloraturas. By highlighting here the strength to be found in communal singing, Bach likewise reveals the raison d‘être of his entire chorale cantata cycle.

Thus fortified, the bass may now revert to a celebratory tone in the following recitative, praising the Christmas miracle as the fulfilment of the patient hope across generations and time. Accompanied by the strings, this paean of praise for God’s love made flesh even liberates the “Lippen Opfer” (our lips’ glad offering); in doing so, Bach proffers a thoroughly selfconfident theological justification for all sacred compositions. Now we can truly welcome the “rechtes Jubeljahr” (year of Jubilee), which, in good antipapal tradition, requires neither pilgrimage nor additional indulgences, because the arrival of the “Jesulein” (Jesus-child) has ushered in a never-ending period of rejoicing. In this recording, we allowed our instrumentalists to join in the joyous music making, a decision that sits well with the transformative promise of the setting, in which even the solemnly dark key of G minor, heir of the powerful Dorian mode, transforms into a tonality of playful jubilation.

Libretto

1. Chor

Das neugeborne Kindelein,

das herzeliebe Jesulein

bringt abermal ein neues Jahr

der auserwählten Christenschar.

2. Arie — Bass

O Menschen, die ihr täglich sündigt,

ihr sollt der Engel Freude sein.

Ihr jubilierendes Geschrei,

daß Gott mit euch versöhnet sei,

hat euch den süßen Trost verkündigt.

3. Rezitativ — Sopran

Die Engel, welche sich zuvor

vor euch als vor Verfluchten scheuen,

erfüllen nun die Luft im höhern Chor,

um über euer Heil sich zu erfreuen.

Gott, so euch aus dem Paradies

aus englischer Gemeinschaft stieß,

läßt euch nun wiederum auf Erden

durch seine Gegenwart vollkommen selig werden:

So danket nun mit vollem Munde

vor die gewünschte Zeit im neuen Bunde!

4. Arie — Terzett (Sopran, Alt, Tenor)

Ist Gott versöhnt und unser Freund,

O wohl uns, die wir an ihn glauben,

was kann uns tun der arge Feind?

sein Grimm kann unsern Trost nicht rauben;

Trotz Teufel und der Höllen Pfort,

ihr Wüten wird sie wenig nützen:

das Jesulein ist unser Hort.

Gott ist mit uns und will uns schützen.

5. Rezitativ — Bass

Dies ist ein Tag, den selbst der Herr gemacht,

der seinen Sohn in diese Welt gebracht.

O selge Zeit, die nun erfüllt!

o gläubig’s Warten, das nunmehr gestillt!

o Glaube, der sein Ende sieht!

o Liebe, die Gott zu sich zieht!

o Freudigkeit, so durch die Trübsal dringt

und Gott der Lippen Opfer bringt!

6. Choral

Es bringt das rechte Jubeljahr,

was trauren wir denn immerdar?

Frisch auf! itzt ist es Singens Zeit,

das Jesulein wendt alles Leid.

Daniel Johannsen

Reflection on J. S. Bach’s cantata “Das neugeborne Kindelein”, BWV 122

– Presented for the J. S. Bach Foundation St. Gallen on 17 December 2021 –

Ladies and gentlemen, dear friends of music,

My dear colleagues

Not only is Olma St. Gallen still very unfamiliar to me as a concert venue (this is only the second time I have been here) – the task of not singing for once after twelve years of belonging to the Bach Foundation Corps, but of addressing contemplative words to you and yours, is absolutely unfamiliar and extremely honourable.

“And what did the Christ Child bring you?” You probably know this post-Christmas question. In Austria, every child is actually asked it at some point. At least for me, the sound of these words brings the past immediately to mind.

Cyriakus Schneegaß, the lyricist of that chorale on which today’s cantata is based, expresses the often once naïve thought refreshingly warmly even as an adult:

Das neugeborne Kindelein,

Das herzeliebe Jesulein,

Bringt abermal ein neues Jahr – das rechte Jubeljahr, heisst es im letzten Vers –

Der auserwählten Christenschar.

A few days ago I was in the Ore Mountains. In the very lightly sugared Ore Mountains. Another “childhood place”, this region – at least the world-famous products of this region are real childhood desiderata. In the evening (and, due to lockdown restrictions, also quite deserted) village of Seiffen, I pressed my nose flat against the wonderfully decorated shop windows, feasted my eyes on all kinds of pyramids and candle arches (and finally had a big bite at the little smoking men and nutcracker kings). I have had the Herrnhut Star at home for a long time, and even the most distant Saxons like to decorate their rooms and verandas with it. (Its ritual hanging at the beginning of Advent was an annual highlight in the parish church of Markt Allhau in southern Burgenland, where my father held his spiritual office for more than 32 years).

Yes, Christmas (whether with or without a religious context) is an express lift to childhood – and if “the child in us” wants to be respected and nurtured, it often lets us know that at Christmas in particular… Perhaps Klaus Groh (we know this poet primarily through Johannes Brahms’ setting of his poems) was also in a discreetly Christmassy mood when he wrote these verses:

Oh, I wish I knew the way back,

The dear way to Kinderland!

O why do I seek happiness

And left the mother’s hand?

O how I long to rest,

Awakened by no aspiration,

To close the tired eyes,

Gently covered by love!

And nothing to research, nothing to spy,

And only to dream light and mild,

Not to see the changing times,

A child for the second time!

I don’t know about you, ladies and gentlemen, but I myself was an extremely bright child, was curious and very much “exploring and peering”. I was particularly fond of exploring various Catholic pulpits (since the Second Vatican Council, these have often gathered a decent layer of dust because of their liturgical ostracism) when my parents took me church sightseeing. When I visited cemeteries, I was also irresistibly attracted by impressively large tombs and mausoleums; I could occupy myself for a long time with their fences and enclosures, and I liked to “stop in” in their niches. (I wonder how I would have reacted if I had been told at the age of five or six that I would one day perform Wilhelm Müller’s “Wirtshaus” – an almost playful metaphor for the Gottesacker – often and often as one of my absolute favourite Schubert songs…) Looking back is often exhilarating – but sometimes it also transfigures and distorts things; sometimes we put thoughts into the heart and words into the mouth of our childlike selves that only a nostalgic adult head can actually think up.

Jesus, “das neugeborne Kindelein” – when he later matured into a man, became a uniquely powerful teacher: What did he say about the youngest, about the right way to deal with them? Let us take one of the most important ancient texts on the subject of understanding childhood, Jesus’ words from Mt. 18 (or Mk. 9 and Lk. 9). It is worthwhile to consider these theses in conjunction with other, (seemingly) unrelated contextual thoughts:

1 Zu derselben Stunde traten die Jünger zu Jesus und sprachen: «Wer ist nun der Größte im Himmelreich?»

2 Und er rief ein Kind zu sich und stellte es mitten unter sie

3 und sprach: «Wahrlich, ich sage euch: Wenn ihr nicht umkehrt und werdet wie die Kinder, so werdet ihr nicht ins Himmelreich kommen.

4 Wer nun sich selbst erniedrigt und wird wie dieses Kind, der ist der Größte im Himmelreich.

5 Und wer ein solches Kind aufnimmt in meinem Namen, der nimmt mich auf.

6 Wer aber einen dieser Kleinen, die an mich glauben, zum Bösen verführt, für den wäre es besser, daß ein Mühlstein um seinen Hals gehängt und er ersäuft würde im Meer, wo es am tiefsten ist.

7 Weh der Welt der Verführungen wegen! Es müssen ja Verführungen kommen; doch weh dem Menschen, der zum Bösen verführt!

8 Wenn aber deine Hand oder dein Fuß dich verführt, so hau sie ab und wirf sie von dir. Es ist besser für dich, daß du lahm oder verkrüppelt zum Leben eingehst, als daß du zwei Hände oder zwei Füße hast und wirst in das ewige Feuer geworfen.

9 Und wenn dich dein Auge verführt, reiß es aus und wirf’s von dir. Es ist besser für dich, daß du einäugig zum Leben eingehst, als daß du zwei Augen hast und wirst in das höllische Feuer geworfen.

10–11 Seht zu, dass ihr nicht einen von diesen Kleinen verachtet. Denn ich sage euch: Ihre Engel im Himmel sehen allezeit das Angesicht meines Vaters im Himmel.

12 Was meint ihr? Wenn ein Mensch hundert Schafe hätte und eins unter ihnen sich verirrte: Läßt er nicht die neunundneunzig auf den Bergen, geht hin und sucht das verirrte?

13 Und wenn es geschieht, dass er’s findet, wahrlich, ich sage euch: Er freut sich über dieses eine mehr als über die neunundneunzig, die sich nicht verirrt haben.

14 So ist’s auch nicht der Wille bei eurem Vater im Himmel, daß auch nur eines von diesen Kleinen verloren werde.»

I made some interesting discoveries while researching this text. In his famous “Institutio oratoria”, Quintilian (* c. 35; † c. 96) sets out convictions with which he seems to vividly agree with Jesus’ thoughts: “Dass aber die Schüler beim Lernen geprügelt werden, wie sehr es auch üblich ist und auch die Billigung des Chrysippos hat [Anm.: Chrysippos von Soloi (279 bis 206 v. Chr.); Schulhaupt der Stoa], möchte ich keineswegs. […] Gegen die schwache und schutzlos dem Unrecht ausgelieferte Jugend darf niemandem zu grosse Freiheit eingeräumt werden.”[1] This seems downright modern; and yet we know that in an empire whose iron foundations included the almost unrestricted patria potestas, minors were not treated squeamishly. How far removed is such a state rationale from Jean-Jacques Rousseau’s educational novel “Émile” (1762) – and how much further still from the educational prohibition of violence, which in my homeland Austria was only given legal form in 1989. In Sweden, which is much more progressive, this happened ten years earlier. And in Switzerland, which is not exactly known as a nation of child beaters, such a passage does not seem to be enshrined in law to this day (as the internet informs me).

“Mozart is too easy for children and too difficult for adults.” This apt phrase is attributed to Artur Schnabel (who is buried in Schwyz, by the way) – and it brings me back to the twelve-year-old Jesus in the temple: another archetypal incident from the Bible in which values are blithely reassessed. The term puer senex, inaccurately translated as “precocious boy”, wants to make the speechless “instinctive knowledge” of a still so young person a little more comprehensible. “Speak at table only when asked! “Maybe some of you had to be told this in your childhood…

An apocryphal writing from the time of the Bible’s origin is the so-called “Infancy Gospel of Thomas”, which, no, not the apostle Thomas, but “Thomas the Israelite” wrote in the 2nd century – as a fascinating and “typically oriental” narrative. Our Lord and Saviour is presented to us as a “wild boy”: He is an often really precocious, impatient, impetuous “spiritual Harry Potter”, who becomes aware of his supernatural powers in amazement (at times also frighteningly) and who is even capable of some cruelty in this process of self-appreciation. Yes, he sometimes appears downright insolent – especially towards his father Joseph, who appears much more prominently in this not very extensive text document than his wife Mary. One is tempted to recognise a certain intention on the part of the author: namely, to question the type of unrestrained patriarchy and even to dismantle it to some extent. However, this Gospel of the Childhood also contains the topoi well known from the four canonical Gospels: Feeding, healing and raising miracles. One of these legends even made it into the iconography of the late Middle Ages: that of the bringing to life of doves formed from lumps of clay; the boy Jesus is scolded for having carried out such manual labour on the Sabbath; in reaction to this rebuke, he breathes on the two creatures and they immediately escape his hands as living creatures. This incident is depicted on one of the magnificent ceiling panels in the Reformed church of Zillis in Graubünden.

The young Samuel is described to us in a completely different way, whom his mother Hannah, out of gratitude for the answer to her prayer (she had begged God for a son), gave into the care of the temple priest Eli at the age of three, so that he could prepare the boy for a spiritual life. Samuel’s “receptivity” to God’s call and will, his touchingly courageous answer “Speak, Lord, for your servant hears” may have been what Jesus had in mind when he recommended the unconditional example of the child to his adult listeners, when he literally and physically placed the child “in the centre”.

I would like to be even more general and now turn to the concept of the child in the Bible in general. The expression “children of Israel” for the entirety of the people in all its generations is encountered at every turn in the Tanakh. It seems particularly apt when it refers to the grumbling, rebellious, easily manipulated crowd of desert wanderers in Genesis – but this presumptuous view, often accompanied by a certain shaking of the head and smirking, would again contradict Jesus’ intentions!

Incidents with children, parent-child constellations in the Old Testament – some of these stories make me shudder, because they are anything but children’s stories: First of all, there is Abraham’s human sacrifice of his only son Isaac, ordered by God and only averted at the last moment by his intervention. The spirit can only rebel at this! And the mind becomes even angrier, the spirit even more upset, when it comes to the successful general Jephta killing his adolescent daughter: He had previously vowed, headless and heartless, to sacrifice the first creature he should meet when he arrived home, as a thank-you gift for victory. I have portrayed this tragic hero, the judge Jephta, in no less than two productions on the opera stage, in Handel’s last oratorio of the same name (a great work) – and even though his librettist Thomas Morell graciously allows an “Angelus ex machina” to intervene at the last moment, the madness of this story still sticks in my bones. (That these two episodes are in all likelihood a kind of “deterrent legislation” with regard to frivolous vows and votives, which in no way correspond to real events, may be postulated in the context of my remarks without further elaboration and justification). Nevertheless, this topos is something that ancient drama (and subsequently opera seria) also dealt with intensively: One need only think of the mythological figures Iphigenia and Idamante (Mozart’s “Idomeneo”).

We also encounter a generalising, “inclusive concept of children” in the writings of the New Testament – especially in the epistles we are addressed there as children of God: “Sehet, welch eine Liebe hat uns der Vater erzeigt, dass wir Gottes Kinder sollen heißen!” (1 John 3:1) And of course a distinction is made between the children of light / day and those of darkness / sin. Paul affirms in the Epistle to the Romans (ch. 8, v. 14): “Denn welche der Geist Gottes treibt, die sind Gottes Kinder.” But he – after all one of the most ardent followers of Christ – seems at times also to have regarded Jesus’ understanding of childhood in a somewhat more differentiated, individualistic way when he writes: “Liebe Brüder, werdet nicht Kinder an dem Verständnis; sondern an der Bosheit seid Kinder, an dem Verständnis aber seid vollkommen.” (1 Cor. 14:20) So the child who is by all means “not quite perfect”: an object of contradiction right up to the present day (with its often so contradictory educational concepts).

Now I would like to turn to Johann Sebastian Bach, a last-born child (of a total of eight siblings), who became a father for the first time at the age of 23 and for the last time at 57 (by the way, these were daughters respectively: Catharina Dorothea and Regina Susanna). Dear friends, now just let the pure facts sink in, this list of 20 people together with their dates of life. You all know that the great Thomaskantor was survived by only nine of his children (I have highlighted them in bold).

From the marriage with his first wife Maria Barbara, née Bach (1684-1720):

Catharina Dorothea (1708-1774)

Wilhelm Friedemann, the Dresden or Halle Bach (1710-1784)

Johann Christoph (*/† 1713)

Maria Sophia (*/† 1713)

Carl Philipp Emanuel, the Berlin or Hamburg Bach (1714-1788)

Johann Gottfried Bernhard (1715-1739), 24 years old

Leopold Augustus (1718-1719)

From the marriage with Anna Magdalena, née Wilcke (1707-1760):

* Christiana Sophia Henrietta (1723-1726)

Gottfried Heinrich (1724-1763)

* Christian Gottlieb (1725-1728)

Elisabeth Juliana Friederica, called “Liesgen” (1726-1781)

* Ernestus Andreas (*/† 1727)

* Regina Johanna (1728-1733)

* Christiana Benedicta (*/† 1730)

* Christiana Dorothea (1731-1732)

Johann Christoph Friedrich, the Bückeburg Bach (1732-1795)

* Johann August Abraham (*/† 1733)

Johann Christian, the Milan or London Bach (1735-1782)

Johanna Carolina (1737-1781)

Regina Susanna (1742-1809)

* Seven children died between 1726 and 1733, two of them in the “B minor Mass year” of 1733.

My penchant for statistics now makes me even more precise; here is the frightening list of those “newborn infants” who died to Johann Sebastian Bach:

1713: The children “No.” 3 & 4, the twins Johann Christoph (at birth) and Maria Sophia (at 4 weeks).

1727: No. 12, Ernestus Andreas (2 days)

1730: No. 14, Christiana Benedicta (4 days)

1733: No. 17, Johann August Abraham (1 day)

Was Bach – with all his evident striving from the very beginning, embedded in an extremely ambitious musical dynasty – a “child”? (Did children in the era before Pestalozzi and Fröbel even have anything like what we might call our concept of childhood?) Soon after his ninth birthday his mother died, and shortly before his tenth he was an orphan. Bach was a childhood expert in joys and sorrows: both in his own body and in view of his numerous descendants…

I would like to leave the last word to the multi-talented Austrian church musician, theologian and philosopher, the Premonstratensian Rupert Gottfried Frieberger; he should have offered his reflection on BWV 127 on 24 February 2017 in Trogen – in his place spoke the oncologist Daniel Büche, a proven palliative physician; how fitting: for Rupert succumbed to his severe cancer on 16 October 2016. I discovered a homily entitled “Sie fanden das Kind” in one of his many books, a Christmas sermon collection[2], and read from it:

Sie fanden das Kind. Vielleicht sind wir zu groß geworden, vielleicht haben wir ein zu dickes Fell bekommen, vielleicht hat uns der Fortschritt die Augen angebrannt, vielleicht haben wir zu viele persönliche Entschuldigungen, vielleicht stolpern wir über die Institution Kirche, vielleicht warten wir zu laut auf den großen Mann. Der große Mann kommt nicht, denn der kleine Bruder von Bethlehem ist schon da.

Sie fanden das Kind. Der Weg vom Hirtenfeld bis Bethlehem ist nicht weit, aber die Schafe müssen zurückgelassen werden: der Stolz, das Besserwissen, die Gier und der Trieb.

Der Weg vom Hirtenfeld bis Bethlehem ist nicht weit, aber man wird sich durchfragen müssen ‒ und wird in Kauf nehmen müssen, angeprangert zu werden, mißverstanden und unverstanden zu sein, wenn man «nur» das Kind finden will, den nackten kleinen Bruder von Bethlehem. […]

Es gibt keinen wohlmeinenderen Weihnachtswunsch an alle Christen, Nicht-mehr-Christen und Unchristen als den, sie möchten das Kind finden.

Denn wer wollte, daß wir erst durch andere Nächte hindurchmüssen, bevor wir atomisiert als müdes Häuflein endlich durch die Sternenpracht der Heiligen Nacht wanken werden?

Die Sehnsucht der Menschheit ist so groß wie die Erde, deshalb ist die Hoffnung der Erde so groß wie der kleine Bruder von Bethlehem, wie das göttliche Kind, der gütige und allmächtige und menschenfreundliche Gott.

Er möge in dieser heiligsten Nacht die Trauernden trösten, den Kranken seine Hilfe anbieten, den Glücklichen ihr Glück erhalten, den Hungernden ein Geschenk senden, die Einsamen besuchen mit seiner Gnade, den Ratlosen ein Licht entzünden, die Verzweifelten mit einer Freude retten; er möge uns alle das Kind finden lassen, den kleinen Bruder von Bethlehem, den großen Gott des Himmels.

Amen!

This text has been translated with DeepL (www.deepl.com).

[1] Zitiert nach: Rahn, Helmut: «Quintilian, Ausbildung des Redners, Zwölf Bücher, Lateinisch und Deutsch», 2 Bände, Darmstadt 31995.

[2] Frieberger, R. G.: «Ich steh an deiner Krippen hier», Steinbach an der Steyr 2002; die Publikation ist hier online frei zugänglich: https://issuu.com/schlaeglmusik/docs/ich_steh_an_deiner_krippen