Sei Lob und Ehr dem höchsten Gut

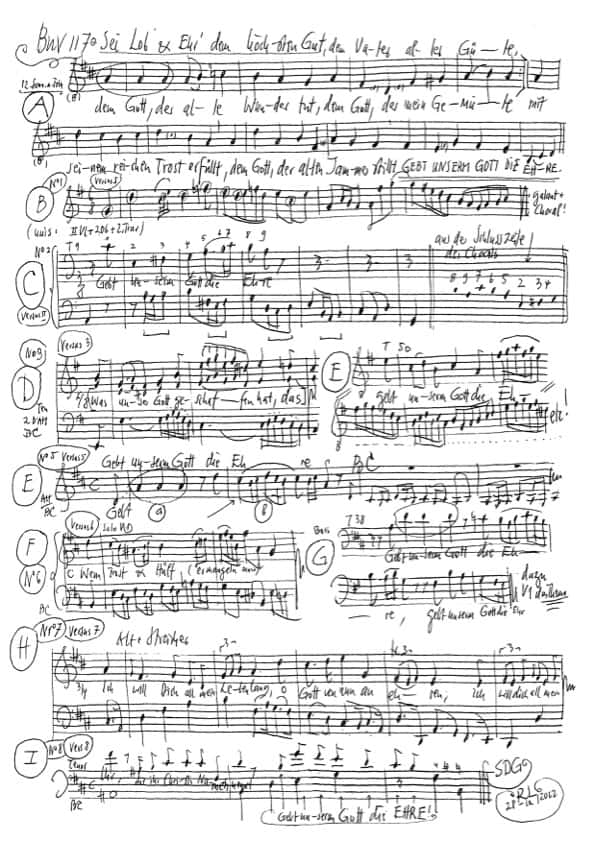

BWV 117 // Unspecified occasion

(Give laud and praise the highest good) for alto, tenor and bass, vocal ensemble, transverse flute I+II, oboe I+II, (oboe d’amore), strings and basso continuo

Would you like to enjoy our videos ad-free? Subscribe to YouTube Premium now...

Workshop

Reflective lecture

Choir

Soprano

Jessica Jans, Jennifer Ribeiro Rudin, Simone Schwark, Noëmi Sohn Nad, Baiba Urka, Mirjam Wernli

Alto

Antonia Frey, Francisca Näf, Alexandra Rawohl, Jan Thomer, Sarah Widmer

Tenor

Clemens Flämig, Achim Glatz, Tobias Mäthger, Nicolas Savoy

Bass

Jean-Christophe Groffe, Johannes Hill, Grégoire May, Daniel Pérez, William Wood

Orchestra

Conductor

Rudolf Lutz

Violin

Renate Steinmann, Monika Baer, Patricia Do, Claire Foltzer, Elisabeth Kohler, Salome Zimmermann

Viola

Susanna Hefti, Matthias Jäggi, Stella Mahrenholz

Violoncello

Martin Zeller, Hristo Kouzmanov

Violone

Markus Bernhard

Transverse flute

Tomoko Mukoyama, Rebekka Brunner

Oboe/Oboe d’amore

Clara Espinosa, Amy Power

Bassoon

Susann Landert

Harpsichord

Thomas Leininger

Organ

Nicola Cumer

Musical director & conductor

Rudolf Lutz

Workshop

Participants

Rudolf Lutz, Pfr. Niklaus Peter

Reflective lecture

Speaker

Caroline Schröder Field

Recording & editing

Recording date

21/10/2022

Recording location

Trogen AR (Schweiz) // protestant church

Sound engineer

Stefan Ritzenthaler

Producer

Meinrad Keel

Executive producer

Johannes Widmer

Production

GALLUS MEDIA AG, Schweiz

Producer

J.S. Bach-Stiftung, St. Gallen, Schweiz

Librettist

First performance

In 1731 – Schlosskirche (castle church) in Weissenfels

Text

Johann Jakob Schütz

Libretto

1. Chor

Versus 1

Sei Lob und Ehr dem höchsten Gut,

dem Vater aller Güte,

dem Gott, der alle Wunder tut,

dem Gott, der mein Gemüte

mit seinem reichen Trost erfüllt,

dem Gott, der allen Jammer stillt.

Gebt unserm Gott die Ehre!

2. Rezitativ — Bass

Versus 2

Es danken dir die Himmelsheer,

o Herrscher aller Thronen,

und die auf Erden, Luft und Meer

in deinem Schatten wohnen,

die preisen deine Schöpfersmacht,

die alles also wohl bedacht.

Gebt unserm Gott die Ehre!

3. Arie — Tenor

Versus 3

Was unser Gott geschaffen hat,

das will er auch erhalten;

darüber will er früh und spat

mit seiner Gnade walten.

In seinem ganzen Königreich

ist alles recht und alles gleich.

Gebt unserm Gott die Ehre!

4. Choral

Versus 4

Ich rief dem Herrn in meiner Not:

Ach Gott, vernimm mein Schreien!

Da half mein Helfer mir vom Tod

und ließ mir Trost gedeihen.

Drum dank, ach Gott, drum dank ich dir;

ach danket, danket Gott mit mir!

Gebt unserm Gott die Ehre!

5. Rezitativ — Alt

Versus 5

Der Herr ist noch und nimmer nicht

von seinem Volk geschieden,

er bleibet ihre Zuversicht,

ihr Segen, Heil und Frieden;

mit Mutterhänden leitet er

die Seinen stetig hin und her.

Gebt unserm Gott die Ehre!

6. Arie — Bass

Versus 6

Wenn Trost und Hülf ermangeln muß,

die alle Welt erzeiget,

so kömmt, so hilft der Überfluß,

der Schöpfer selbst, und neiget

die Vateraugen denen zu,

die sonsten nirgend finden Ruh.

Gebt unserm Gott die Ehre!

7. Arie — Alt

Versus 7

Ich will dich all mein Leben lang,

o Gott, von nun an ehren;

man soll, o Gott, den Lobgesang

an allen Orten hören.

Mein ganzes Herz ermuntre sich,

mein Geist und Leib erfreue sich.

Gebt unserm Gott die Ehre!

8. Rezitativ — Tenor

Versus 8

Ihr, die ihr Christi Namen nennt,

gebt unserm Gott die Ehre!

Ihr, die ihr Gottes Macht bekennt,

gebt unserm Gott die Ehre!

Die falschen Götzen macht zu Spott,

der Herr ist Gott, der Herr ist Gott:

Gebt unserm Gott die Ehre!

9. Chor

Versus 9

So kommet vor sein Angesicht

mit jauchzenvollem Springen;

bezahlet die gelobte Pflicht

und laßt uns fröhlich singen:

Gott hat es alles wohl bedacht

und alles, alles recht gemacht.

Gebt unserm Gott die Ehre!

Reflection Caroline Schröder Field

BWV 117 – 21 October 2022

My mother is a simple woman. She has given birth to four children. She is 85 years old. For a few days in the nursing home in a small village in the Bergisches Land, she has been fighting despondency, despair and shame. Thin and small like a bird that has fallen from its nest. Her hands lie on the bedspread, almost transparent, while she sleeps. Mother’s hands.

Helene Werthemann comes from an old Basel family. She is a theologian, holds a doctorate and a habilitation. She is 95 years old. She lives in her parents’ house, which is quietly and unresistingly out of time next to the sprawling new buildings of the university hospital. When she studied, theology belonged to men. She wrote a dissertation on Bach’s cantatas – no, on the Old Testament histories in the texts of his cantatas. She became a Bach connoisseur and Bach lover. His music opens up her faith. I listened to our cantata with her.

Neither my mother nor Helene Werthemann can be here today.

My mother prayed with us when we were little. Every evening she sat on the edge of our bed. “I am tired, go to rest, close my little eyes. Father, let your eyes be over my little bed.” In these October days, I sit at her bedside and pray with her the prayer of my childhood. She folds her hands and we both entrust ourselves to the Father’s eyes looking down on us. That’s all it takes.

In the bishop’s courtyard of the Basel Reformed Church hang the portraits of the antistes and church council presidents. They look down sternly from their heights, just as one of them looked down many years ago on Helene Werthemann, who ventured into theology as a woman. Theology is a man’s world. But praying is mostly learned through the mothers.

Mother’s hands. Father eyes. Someone in the 17th century actually got serious about the fact that God can have both: Mother’s hands and father’s eyes.

That God can meet people in a motherly and fatherly way, protecting, caring, watching, commanding, taking an interest. Johann Jakob Schütz. A Pietist in a time when Lutheran orthodoxy still resisted Pietism. A chiliast, one with a fervent expectation of the end times. A suspect, but one who thought of God in a motherly-fatherly way, quite calmly and without any pathos, simply because he knew the Bible. Psalm 131:2: “Truly my soul has become still and quiet, like a little child with its mother”. Or Isaiah 66:13: “I will comfort you as a mother comforts her child.” Those who read expectantly in both Testaments and familiarise themselves with the whole polyphonic library of the Church will also sooner or later come across the maternal side of God. Mother’s hands. Father eyes.

Helene Werthemann told me about Karl Barth’s reaction to her dissertation. Karl Barth loved Mozart. Helene Werthemann perhaps as well, I will ask her. But above all, she loves Bach. Karl Barth’s verdict on the young Werthemann’s dissertation: “… confirms to me that Bach was the Old Testament scholar and Mozart the New Testament scholar. “If this is supposed to have included a value judgement, it may have hurt Mrs Werthemann. I will ask her.

“Be praise and honour to the highest good” – is full of echoes of the whole Bible. The song of a pietist separatist, transformed into a cantata by a Lutheran of the old school. Johann Sebastian Bach knew about the differences between his confession and the Reformed, about the great distance to Catholicism, about the quarrels between Pietism and Orthodoxy. And he found a language in music that could be understood by all. Music, which he mastered in so many practical ways and worked tirelessly, to perfect, was his language of love. His language of love for God. “Give glory to our God. “

He saw himself quoted in this recurring line of the chorale, as he signed many of his scores with “Soli Deo Gloria”: “Glory to God alone”. But of course he also saw Moses quoted. And the Philippians hymn from the New Testament. It is the whole Bible, Old and New, First and Second Testaments, that teaches us to love God. And the music in its triad of delectare – docere – movere (delight, teach and move) takes up this teaching, lets itself be guided by it, penetrated by it, moved by it: Soli Deo Gloria. A mirror that reflects the light and thus becomes a source of light itself. And whoever looks into it learns cheerfulness. And nothing is more important than serenity. Cheerfulness is not “laughter that makes your head spin”. Serenity is the serenity that comes from faith. It is not the seriousness but the serenity of faith that is beyond doubt. The serenity of faith in which we are already where, historically and humanly speaking, we are not yet for a long time and probably never will be: in a world in which God’s initial judgement of his creation (Genesis 1:31: “And God saw all that he had made, and behold, it was very good”) is so proven true that all pain, all misery, all sin are water under the bridge. In a world where the words of the chorale come to everyone’s lips without any need to argue about it anymore: “God has considered it all well. And made everything, everything right.”

Experience teaches us doubt. History teaches us doubt. Putin’s missile attack on Kiev and other cities in Ukraine teaches us doubt. Every war and every misery does. The cosmic liturgy of all creatures, the belief that creation is not yesterday’s news but still sustains us now: “What our God has created, that he will also sustain”, the direct experience of a single answer to prayer – and who says that doesn’t happen! – leave doubt behind in Christ’s name. In Christ’s name, that is, not apparent to all, but given only to those who still know what faith speaks of: of the triune God, of the incarnation and self-abasement of the Son of God into the worst lostness and God-forsakenness of human existence. This is what faith speaks of in Christ’s name. The cantata text only touches on this, but this is the real centre: that all singing, all praising God is only possible from Christ.

When we were sick as children and waited for the thermometer to read body temperature, our mother would sing a song that I have since come to associate not with Christmas, but with a fever-heated head and the comforting security of being near one’s mother.

She sang: “Every year the Christ child comes. Down to earth, where we humans are. He enters every home with his blessing, goes in and out with us on all our paths. Stands also by your side, quiet and unrecognised, that he may faithfully guide you by the dear hand.”

With this silent and unrecognised Christ at one’s side, it is possible to praise God even when one feels sick and miserable. For in him man is set right before God. Not only his head, but his heart, spirit and body. The fruit of this setting right is nothing other than the hymn of praise, doxological words that cross the threshold to music, to chorale, to cantata, and back again, as if by themselves. Encompassing the sermon so that it does not “slip”. Thus everything, faith and life, word and music, sermon and cantata, is irradiated by a serenity beyond all doubt.

It is this serenity of faith that is so different from the zeal of faith. But for anyone with ears to hear, or anyone familiar with the biblical texts, the zealots of faith are also on the scene in the chorale. Perhaps because its author, Johann Jakob Schütz, was one himself. But mainly because the spirit of Elijah is evoked in the words of the chorale. “The false idols make a mockery! The Lord is God, the Lord is God!” There he is: Elijah, the warrior of God, who conjured up a judgement of God on Mount Carmel, who demonstrated the impotence of religious competition in a grandly staged show battle and wrestled the confession of YHWH from all the people. Who, in his zeal for the First Commandment – and isn’t Bach’s “Soli Deo Gloria” a variant of the First Commandment? – killed his opponents and immediately fell into a depression of exhaustion. From which no one but God alone could bring him out.

So it is with man who sins most precisely where he thinks he is arguing most for God. Only God can save him. And God does: In Christ, “the Creator Himself inclines the Father’s eyes to those who otherwise find nowhere to rest.” Elijah was also found again when he was in the desert.

It is precisely for the sake of faith that the zealot must be sent into the wilderness. Nothing has the zealot more to learn than God’s silent appearance. Than God’s game of hide and seek between the lines. Just as numerous allusions to the Trinity are hidden in a Bach cantata – and can be discovered at the same time if one is familiar with numerical mysticism. Perhaps the zealots of faith just want too much too fast, while the serene have all the time in the world to see how parallels intersect in the infinite and how contradictions are resolved and opposites reconciled. “Soli Deo Gloria” is eschatology, is future music. In this life, we are all overwhelmed by it. Even those who take it upon themselves to do so. Too soon, “Soli Deo Gloria” can become a battle cry of some against others, as Elijah staged on Mount Carmel. The words “Soli Deo Gloria” can be misused by man to wage war. They are, like all words, at the mercy of man. “Give glory to our God”, this recurring chorale line, is the one that makes the most sense to me when I imagine that one day we will rub our eyes in surprise, as if we were awakening, when we discover that we and the others are one; the people of other faiths are human beings like us; part of the same cosmic liturgy in which we all seek our words, our language, to express our love.

Oh yes. When we were very small, too small for prayers, my mother first sang us a much simpler song when we had a fever, and I can clearly see the movement of her hands:

“As the flag on the tower can turn in the wind and storm, so shall my hands turn that it is a joy to behold. Mother’s hands. What would the father’s eyes be without the mother’s hands.

There are different languages of love. If one does not speak the same language in love, the suspicion always arises that it cannot be love with the other person. Theology and music are also different languages. Helene Werthemann has familiarised herself with both and thus built a valuable bridge for me. Which I needed. Because I too am a simple woman.

This text has been translated with DeepL (www.deepl.com).