Weinen, klagen, sorgen, zagen

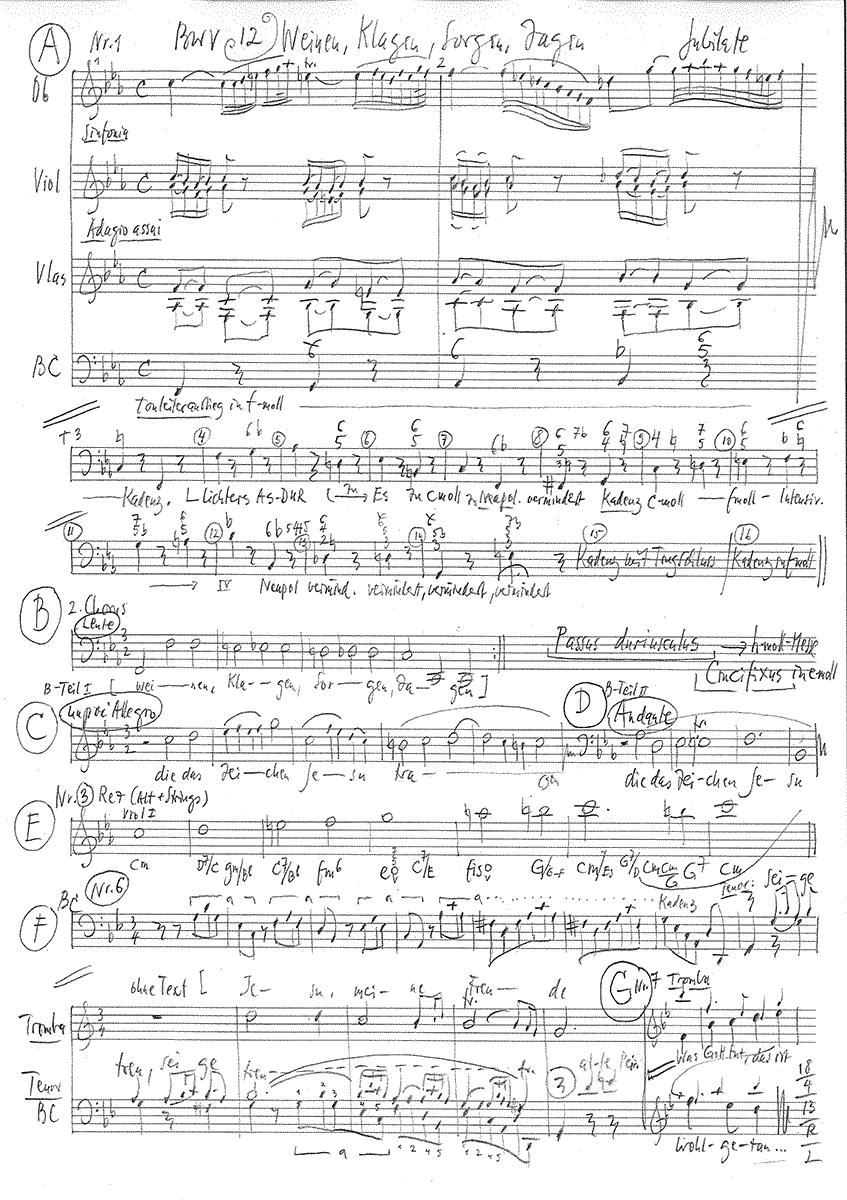

BWV 012 // For Jubilate (Third Sunday after Easter)

(Weeping, Wailing, Grieving, Fearing) for alto, tenor and bass, vocal ensemble, tromba, oboe, bassoon, strings and continuo

Would you like to enjoy our videos ad-free? Subscribe to YouTube Premium now...

Workshop

Reflective lecture

Bonus material

Choir

Soprano

Olivia Fündeling, Susanne Seitter, Noëmi Sohn Nad, Noëmi Tran Rediger, Alexa Vogel

Alto

Antonia Frey, Katharina Jud, Alexandra Rawohl, Damaris Rickhaus, Lea Scherer

Tenor

Clemens Flämig, Nicolas Savoy, Walter Siegel

Bass

Fabrice Hayoz, Philippe Rayot, Manuel Walser, William Wood

Orchestra

Conductor

Rudolf Lutz

Violin

Plamena Nikitassova, Dorothee Mühleisen, Christine Baumann, Yuko Ishikawa, Elisabeth Kohler, Ildiko Sajgo

Viola

Martina Bischof, Peter Barczi, Joanna Bilger, Sarah Krone

Violoncello

Maya Amrein, Hristo Kouzmanov

Violone

Iris Finkbeiner

Oboe

Katharina Arfken

Bassoon

Susann Landert

Tromba da tirarsi

Patrick Henrichs

Organ

Nicola Cumer

Musical director & conductor

Rudolf Lutz

Workshop

Participants

Karl Graf, Rudolf Lutz

Reflective lecture

Speaker

Andrea Köhler

Recording & editing

Recording date

04/19/2013

Recording location

Teufen

Sound engineer

Stefan Ritzenthaler

Director

Meinrad Keel

Production manager

Johannes Widmer

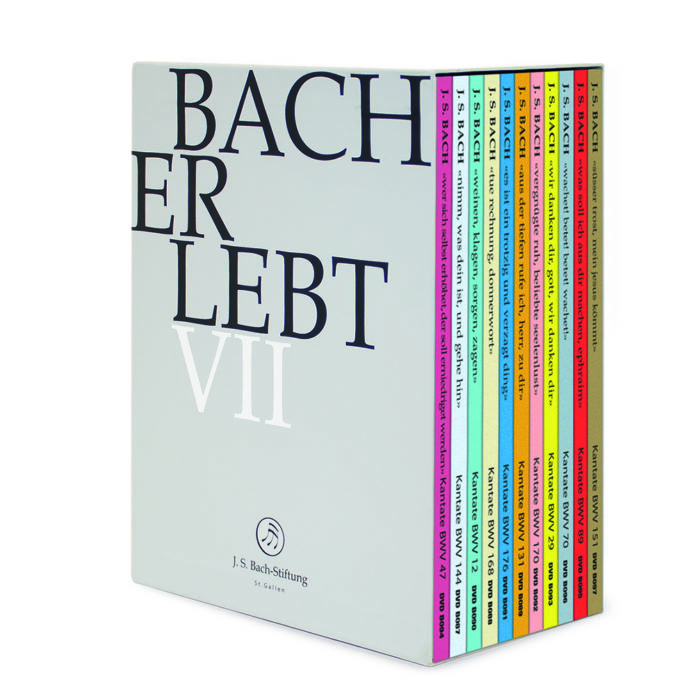

Production

GALLUS MEDIA AG, Switzerland

Producer

J.S. Bach Foundation of St. Gallen, Switzerland

Librettist

Text

Poet as yet unknown,

probably Salomo Franck (1659–1725)

Text No. 3

Quote from Acts of the Apostles 14:22

Text No. 7

Samuel Rodigast (1649–1708)

First performance

Jubilate,

22 April 1714

Libretto

1. Sinfonia

2. Chor

Weinen, Klagen,

Sorgen, Zagen,

Angst und Not

sind der Christen Tränenbrot,

die das Zeichen Jesu tragen.

3. Rezitativ (Alt)

«Wir müssen durch viel Trübsal in das Reich Gottes eingehen.»

4. Arie (Alt)

Kreuz und Kronen sind verbunden,

Kampf und Kleinod sind vereint.

Christen haben alle Stunden

ihre Qual und ihren Feind,

doch ihr Trost sind Christi Wunden.

5. Arie (Bass)

Ich folge Christo nach,

von ihm will ich nicht lassen

im Wohl und Ungemach,

im Leben und Erblassen.

Ich küsse Christi Schmach,

ich will sein Kreuz umfassen.

Ich folge Christo nach,

von ihm will ich nicht lassen.

6. Arie (Tenor)

Sei getreu, alle Pein

wird doch nur ein Kleines sein.

Nach dem Regen

blüht der Segen,

alles Wetter geht vorbei,

sei getreu, sei getreu.

7. Choral

Was Gott tut, das ist wohlgetan,

dabei will ich verbleiben,

es mag mich auf die rauhe Bahn

Not, Tod und Elend treiben,

so wird Gott mich

ganz väterlich

In seinen Armen halten,

drum lass ich ihn nur walten.

Andrea Köhler

“To be in the world is to be chained to worry”.

Bach’s cantata “Weinen, Klagen, Sorgen, Zagen” reminds us that the renunciation of the promise of happiness in the hereafter has bound us entirely to this world and thus to worry. But worry is not only tormenting, it is also our greatest asset.

“Weeping, complaining, worrying, trembling” – this is the staccato of a crisis of trust. It expresses a loss, if not of faith, then of hope that life will ever be kind to us again. But even the dark haunting of the soul draws its pain first from the idea of what one misses in such a situation. What is that? The post-metaphysical individual, who no longer bends his knees and folds his hands as a matter of course, is largely left to his own devices in times of crisis – unless he entrusts himself to the laboratories of the happiness industry. Pharmaceutical research has recognised the sunken horizon of promise in the phenomenon of lowered serotonin levels; it gives chemical nourishment to the messengers of salvation. What was once promised by hope and its pious prophets is now provided by neurotransmitters. And yet their message still needs to be painted on the sky.

“Depression is a defect of the chemical balance, not a weakness of character. There’s a solution for everything. Call 1-800-Help,” reads an advertisement towering into the New York sky at the corner of Broadway and Amsterdam Avenue. So where once there was the invocation of God, today there is the reach for the iPhone. But why has the advertisement been placed so high above our heads? Apparently, the promise of salvation still has to come from above. So this advertisement appeals to our age-old vertical fixation.

“Weeping, lamenting, sorrow, trembling”: Bach’s cantata was premiered in Weimar on 22 April 1714, 300 years ago next year almost to the day; it is set for the third Sunday after Easter, called “Jubilate” in the church calendar. It is based on the Gospel text John 16:16-23 of the Luther Bible, in which Jesus proclaims the promise of the resurrection: “Verily, verily, I say unto you: You will weep and mourn, but the world will rejoice; you will be sad, but your sadness shall be turned into joy.” The cantata, which first attunes us to the expressions of distress, confronts us with the genuine paradox inherent in all hope: “You will weep and lament/ but the world will rejoice” – it is these words which, after a slow lightening of the melody, find a moving echo in the final chorale of this cantata: The concluding chorale is the last verse of a hymn by Samuel Rodigast. The core text, however, was penned by Salomon Franck, the author of most of the cantata texts from Bach’s early Weimar period.

Cantata of the states of mind

“Weeping, lamenting, worrying, trembling”: these are states of mind against which we are no longer easily able to arm ourselves with a divine embrace. How do we deal today with the “sadness clinging to all finite life”, as Schelling put it? Let us stay for a moment with this six-minute dacapo of anguish, the melody of which Bach was later to underlay with the “Cruzifix” of the Mass in B minor, and listen to the meaning of the four initial words:

Weeping – this is the body’s response when a sensation is stronger than our control. We weep where language fails – or at least is insufficient to express our distress. Crying – with this emotion we come into the world. With the first cry, breath flows into our lungs and binds us to the metabolism with all living things. Even our tears are, soberly considered, a product of metabolism. But the fact that this form of expression is reserved for us humans makes tears a specifically human characteristic that cannot be grasped by natural science. Tears, although a physical reaction, are a product of consciousness – and not least the secretion of the knowledge of our mortality. Animals do not cry.

So let’s move on to the second concept: lamentation. It is said that homo sapiens first found language in lament for a loved one – and all language was once song. It is no coincidence that the most heartfelt music is usually found in the parts of lamentation; perhaps even more than joy, suffering is first a sound phenomenon. As a ritualised form of remembrance, the lamentation of the dead was originally accompanied by a strongly theatrical discharge of affect, by howling and screaming – and in many parts of the world it still is today. In our latitudes, on the other hand, the lament usually takes place in silence, when the funeral ceremonies are over.

War declared on mourning

The anxiety with which mourners are regarded by their environment today is probably also an indicator that the inflationary confession push that trumpets our most fundamental feelings on talk shows or in twitters and tweets is not able to replace the erosion of rituals. I live in a country where weeping and lamenting, moaning and wailing are catered for around the clock with high viewing figures; the lament for the dead in particular – as the boom in mourning memoirs shows – has considerable bestseller potential. And yet war has been declared on real mourning. It is probably no coincidence that the latest edition of the diagnostic manual for physicians and psychiatrists has been supplemented by a clinical picture that goes by the beautiful name of prolonged grief disorder. Since then, this finding, which, by the way, already applies after two weeks, has been dictated in the media with the furore that such diagnoses always receive when they play into the pockets of the pharmaceutical industry.

“Christians have all hours, their torment and their enemy/ But their consolation are Christ’s wounds”: The second aria of our cantata, which – at least so it seems to me – already orchestrates a tentative confidence, has another proposal ready for us. Can we still feel this consolation today, the consolation that springs from the agony of another human being, mind you?

It was on an Easter night seven years ago that I understood the meaning of these verses, so to speak, with body and soul. I was lying in a New York hospital after a serious operation and found myself physically and psychologically on an abyss that is no longer accessible to any rational consciousness. In the room with me was a woman who prayed aloud all night long. In her invocation to Jesus, this woman blamed herself for her pain – indeed, she affirmed the operation she had just survived as a punishment for her transgressions. Now such a form of retribution theology is conceivably foreign to me. But what I understood that night was the deeply rooted human need for a symbolic representation for overwhelming agony. Perhaps for the first time, I realised the whole dimension of consolation that lies in the symbolic representation of Christ in suffering. But what gave me this insight above all was the music. I listened to the St Matthew Passion over and over again that night, not only to escape the prayer of my bedmate but also to escape the American form of consolation, the incessantly running television, and I am not going too far if I claim that it was to a not inconsiderable extent this music that saved me from despair.

Gardens are peepholes into paradise

Zagen – this is not only a word that has been largely banished from the vocabulary, it is also conceivably alien to the cool habitus that one has to put on these days. Zagen – I always hear tenderness in this word – and not only because of the same initial letters. Trepidation is the moment when courage leaves us and despair approaches. Faltering – hesitation is not far away – that inhibition that places us in the space of decision. Whoever hesitates, hesitates, hesitates, is abandoned to his own doubts and fears, exposed to chance, arbitrariness, in short: to worry.

Of all the four words in the opening line of this cantata, worry is closest to fear. Worry is a night visitation, it likes to lie in wait for us between four and five in the morning, at the pale hour of the executioner. In “Being and Time”, Martin Heidegger defined Dasein itself as Sorge and thus placed human life in the dimension of temporality and anxiety – in Dasein zum Tod. And yet worry is not only our worst tormentor, but also our greatest asset.

It was in a biblical garden that worry was brought into the world: through Eve’s bite into the apple we came under the regime of natality and mortality. It was only with Eve’s transgression that the mortal self came into being, which must realise its potential in time – through the care of those who come after us and the memory of our dead, through the cultivation of the earth and that of the soul, through work, art, science and religion.

In his book “Gardens. An Essay on the Human Condition”, the American literary scholar and philosopher Robert Harrison defines horticulture – in its broadest sense – as the archetype of caring concern. Gardens, he writes, “are places that offer a glimpse of paradise in the midst of the fallen world, and the fact that we must create and preserve and care for them is the mark of their origin in the condition after the Fall.”

So it is probably no coincidence that Christ’s loneliest hour, the hour in which he promises to take upon himself the sins of mankind, took place in a garden; the existential solitude of the night in the Garden of Gethsemane, is the scenario from which the Christian myth of the crucifixion draws its power. There is hardly another biblical passage that reaches into the depths of human fear like this one. And yet this is the hour in which hope in despair, that state of mind of which this cantata speaks, is at its greatest: “Father, not as I will, but as you will.” Or, in the words of our final chorale: “What God does is well done/ Therefore I only let him rule.”

For the Enlightenment, which began around the time of Bach’s death, human self-determination was only possible at the price of turning away from the superworld, of liberation from what this cantata so childishly and trustingly calls the “fatherly embrace”. All energy was to be spent only on building heaven on earth. Nevertheless, the expectation that renouncing the vague promise of otherworldly bliss would automatically lead to an improvement of the happiness situation on earth was not fulfilled.

The consolation of music

On the contrary: the price of absolute worldliness is inevitably loss of distance – a loss that exposes us to anxiety in permanence. To be in the world means to be chained to worry, despite all pharmaceutical promises of happiness.

And so we humans of the 21st century are still dependent on that consolation without which “misery, death and distress” would be absolutely unbearable: the consolation of the most metaphysical of all arts: music. Music that, like this cantata, has preserved the promise of resurrection for us and revives it with every performance. And because this cantata is dedicated to the third Sunday after Easter, the “Jubilate”, I would like to conclude by reciting a creative praise that was written a century after Bach, and which praises the ambivalence, the indispensable coexistence of sorrow and cheerfulness. It was written by the English poet Gerard Manley Hopkins and is called “Gescheckte Schönheit” in the German translation by Ursula Clemens and Friedhelm Kemp:

Glory to God for speckled things -.

For skies as dyed as a spotted cow;

For rosy marks all dotty on swimming trout;

Chestnut-fall like fresh coals of fire; Finch-wings;

The field in patches, the meadow, the fallow, and the field;

And all trades, their garments and harness and utensils.

All things strange, original, rare, whimsical;

What ever is changeable, checkered (who knows how?)

With quick, slow; sweet, sour; flashing, dull;

He begets it, whose beauty wandless;

Praise him.

This text has been translated with DeepL (www.deepl.com).