Der Himmel lacht! Die Erde jubilieret

BWV 031 // For The First Day of Easter

(The heavens laugh! The earth doth ring with glory) for soprano, tenor und bass, vocal ensemble, trumpet I–III, timpani, oboe, taille, strings and basso continuo

Would you like to enjoy our videos ad-free? Subscribe to YouTube Premium now...

Workshop

Reflective lecture

Choir

Soprano

Lia Andres, Maria Deger, Stephanie Pfeffer, Simone Schwark, Susanne Seitter, Noëmi Sohn Nad, Noëmi Tran-Rediger, Alexa Vogel, Anna Walker

Alto

Anne Bierwirth, Nanora Büttiker, Antonia Frey, Francisca Näf, Lea Pfister-Scherer

Tenor

Zacharie Fogal, Achim Glatz, Tiago Oliveira, Christian Rathgeber

Bass

Jean-Christophe Groffe, Fabrice Hayoz, Serafin Heusser, Philippe Rayot, Tobias Wicky

Orchestra

Conductor

Rudolf Lutz

Violin

Renate Steinmann, Monika Baer, Claire Foltzer, Elisabeth Kohler, Olivia Schenkel, Petra Melicharek, Salome Zimmermann

Viola

Susanna Hefti, Matthias Jäggi, Stella Mahrenholz

Violoncello

Martin Zeller, Magdalena Reisser

Violone

Guisella Massa

Oboe

Katharina Arfken

Trumpet

Lukasz Gothszalk, Matthew Sadler, Alexander Samawicz

Timpani

Inez Ellmann

Bassoon

Susann Landert

Harpsichord

Thomas Leininger

Organ

Nicola Cumer

Musical director & conductor

Rudolf Lutz

Workshop

Participants

Rudolf Lutz, Pfr. Niklaus Peter

Reflective lecture

Speaker

Christine Blanken

Recording & editing

Recording date

28/04/2022

Recording location

Trogen AR (Schweiz) // Evangelische Kirche

Sound engineer

Stefan Ritzenthaler

Producer

Meinrad Keel

Executive producer

Johannes Widmer

Production

GALLUS MEDIA AG, Schweiz

Producer

J.S. Bach-Stiftung, St. Gallen, Schweiz

Librettist

First performance

21 April 1715, Weimar

Text

Salomo Franck (movements 2–8); Nikolaus Herman (movement 9)

In-depth analysis

BWV 31 was composed for the first day of Easter and, as befits such a key occasion in the church year, is scored for one of the largest ensembles among Bach’s sacred compositions: five vocal parts, a trumpet ensemble as well as a five-voice oboe and string choir. Based on a text from the “Evangelisches Andachts-Opffer” cycle by Salomo Franck, Bach’s main librettist in Weimar, and first performed in 1715 in the chapel of the ducal palace, the compelling Easter music was reperformed several times from 1724 onwards during Bach’s tenure as Thomascantor in Leipzig.

The introductory sonata interprets the Easter feast as a heroic, victorious happening. After opening with unison broken chords that illustrate the global significance of the event, emblematic trumpet signals give way to confident music-making in which the woodwind and string instruments weave a dense fabric of sound.

After this majestic and dense prelude, the opening chorus, which is based on powerful, alternating calls and imitative coloraturas, paves the way for exhilarated rejoicing: indeed, the formal richness and broad scope of the setting represent the meeting of heaven and earth. The changes of tempo and gesture in the recurrent trumpet passages – portraying the peace of the grave and resurrection – hold the movement together, an approach at times reminiscent of Bach’s early sacred concertos and one that distinguishes the work as a milestone in his monthly cantata compositions in Weimar, especially in matters of personal text interpretation.

In the extended bass recitative, the soloist attempts to luxuriate in the dramatic celebration of the resurrection message but is continually propelled forward by the joyous, arioso impetus of the continuo part. In his interpretation of Franck’s textual contrasts, Bach captures what a rendering of biblical truths in the here and now can mean to listeners – and how it can unleash a life-altering vitality.

The ensuing bass aria likewise draws energy from the dotted rhythms of the continuo introduction, thus harking back to the organistic origins of Bach’s compositional activities. Despite the gruff undertones of the accompaniment, the soloist presents a celebratory, elegant cantilena that graciously evokes the priestly aura of the carefully worded praise. The following tenor recitative is a movement of weighty theological import that emphasises the text’s present-day relevance by summoning the devout soul to rise up spiritually with Christ. Here, the notion of abandoning the “tote Werke” (works of dying) and beginning a new life is rendered plausible by Bach and his librettist through their bold equation of the disciples’ flight from the grave with the rush of the faithful to Jesus as the living word.

Through its dance-like attitude and intentional use of inverted motifs in the string parts, the tenor aria shows just how effective this type of down-to-earth encouragement can be. At the same time, the motifs stand equally for the work that lies ahead after the old Adam has been cast off, an earnest notion that is central to this aria despite its bright G-major tonality and liberated vocal cantilena.

The final recitative-aria pair of movements, set for soprano, broadens the cantata’s focus to explore the dimension of eternity and the reunion with Christ that supersedes suffering and death. While the recitative is able to ascend from sounds of painful suffering to radiant splendour, the aria “Letzte Stunde, brich herein” (Final hour, break now forth) numbers among Bach’s most sensitive explorations of our own death and the letting go necessary for later resurrection. Over long notes and sparse individual accents in the continuo, the instrumental solo part (which was probably assigned to the oboe d’amore first in the Leipzig version) with its echoing figures indeed seems to be waiting for the final hour, the arrival of which is evoked by a gentle descending chord from the vocalist. Added to the mix in this entrancing scene is a chorale cantus firmus by unison strings in a comforting middle register. Despite the intentional lack of text here, the careful listener can still detect the hymn as “Wenn mein Stündlein vorhanden ist” (If the hour of my death is at hand) by Nikolaus Herman.

The closing chorale references the same hymn but employs the final verse “So fahr ich hin zu Jesus Christ” (So forth I’ll go to Jesus Christ), which was added by an unknown author in 1575. Thanks to an additional part for unison trumpet and violin, this movement radiates a five-voice brilliance and sense of confident ceremony that no feeling heart can resist.

Libretto

1. Sonata

2. Chor

Der Himmel lacht! Die Erde jubilieret

und was sie trägt in ihrem Schoß.

Der Schöpfer lebt! der Höchste triumphieret

und ist von Todesbanden los.

Der sich das Grab zur Ruh erlesen,

der Heiligste kann nicht verwesen.

3. Rezitativ — Bass

Erwünschter Tag! Sei, Seele, wieder froh!

Das A und O,

der erst und auch der letzte,

den unsre schwere Schuld

in Todeskerker setzte,

ist nun gerissen aus der Not!

Der Herr war tot,

und sieh, er lebet wieder!

Lebt unser Haupt, so leben auch die Glieder!

Der Herr hat in der Hand

des Todes und der Höllen Schlüssel!

Der sein Gewand

blutrot bespritzt in seinen bittern Leiden,

will heute sich mit Schmuck und Ehren kleiden.

4. Arie — Bass

Fürst des Lebens, starker Streiter,

Fürst des Lebens, hochgelobter Gottessohn!

hebet dich des Kreuzes Leiter

auf den höchsten Ehrenthron?

Wird, was dich zuvor gebunden,

nun dein Schmuck und Edelstein?

Müssen deine Purpurwunden

deiner Klarheit Strahlen sein?

5. Rezitativ — Tenor

So stehe dann, du gottergebne Seele,

mit Christo geistlich auf!

Tritt an den neuen Lebenslauf!

Auf! von den toten Werken!

Laß, daß dein Heiland in dir lebt,

an deinem Leben merken!

Der Weinstock, der jetzt blüht,

trägt keine tote Reben!

Der Lebensbaum läßt seine Zweige leben!

Ein Christe flieht

ganz eilend von dem Grabe!

Er läßt den Stein,

er läßt das Tuch der Sünden dahinten

und will mit Christo lebend sein!

6. Arie — Tenor

Adam muß in uns verwesen,

soll der neue Mensch genesen,

der nach Gott geschaffen ist!

Du mußt geistlich auferstehen

und aus Sündengräbern gehen,

wenn du Christi Gliedmaß bist.

7. Rezitativ — Sopran

Weil dann das Haupt sein Glied

natürlich nach sich zieht,

so kann mich nichts von Jesu scheiden.

Muß ich mit Christo leiden,

so werd ich auch nach dieser Zeit

mit Christo wieder auferstehen

zur Ehr und Herrlichkeit

und Gott in meinem Fleische sehen!

8. Arie — Sopran

Letzte Stunde, brich herein,

mir die Augen zuzudrücken!

Laß mich Jesu Freudenschein

und sein helles Licht erblicken!

Laß mich Engeln ähnlich sein!

Letzte Stunde, brich herein!

9. Choral

So fahr ich hin zu Jesu Christ,

mein Arm tu ich ausstrecken;

so schlaf ich ein und ruhe fein;

kein Mensch kann mich aufwecken

denn Jesus Christus, Gottes Sohn,

der wird die Himmelstür auftun,

mich führn zum ewgen Leben.

Christiane Blanken

I was invited to give an impulse here as a Bach researcher. Actually, in introductions I try to present textual and musical and music-historical concerns that are openly revealed in a work or are effective in a hidden way.

Today I would basically like to try something new for me: Today, to a certain extent, I am facing the question of how I, as a Bach researcher at the Bach Archive Leipzig, actually relate to Bach’s music, how I relate to the chequered history of a good 300 years of Bach’s performance practice and where – as a consequence – I see my field of activity, indeed my personal contribution to Bach research.

Easter as the celebration of the new, of that which has just outgrown death, is inseparably linked with spring. Allow me, therefore, an allegorical introduction to the theme from the realm of creation. For I often feel that Bach’s work is something natural – despite all the artistry of the compositions:

I would like to deliberately use a very simple image and compare Bach’s music with an old gnarled tree that fertilises and nourishes its surroundings, that defies the most diverse adversities through the centuries and whose trunk gradually and steadily grows, whose root system is extremely storm-proof … In plain language, of course, I mean that Bach’s music can hardly ever be harmed by different kinds of performance, changing fashions, romanticising adaptations, modernist alienations, since root and trunk are, so to speak, healthy. And the fertilisation, such as Beethoven’s constructive further development of counterpoint in the field of the sonata, chamber music and choral symphonies, is one of the most essential and magnificent aspects of the 300 years of Bach’s reception. And derived from Beethoven, this also fertilised Schubert’s work. (And whom Bach will fertilise in the future is an open question; but it will happen, because the multifaceted energy of Bach’s music continues to overflow and, in a sense, to release ever new energies).

In the meantime, I had been considering another image of nature in preparation for this evening: the onion. (… don’t be surprised – as I said, nature images are more important to me for Bach’s music than comparisons from the history of art or humanity).

Can Bach’s music today perhaps be regarded rather as an onion growing in secret, which is stored for some time after harvesting; but before it is eaten, it must first be skinned, because the outer layers have become inedible in the course of growth … in plain language: that you have to get rid of any performance tradition, any interpretation, before you can get to the inside of the onion to prepare food; in plain language: before every performance, also before every theoretical occupation in Bach research, I have to skin the onion myself, have to see and feel for myself how many layers I have to remove. On the inside, everything interlocks, we find a perfect structure; but isn’t it sometimes stereotypically chopped up by stereotypical performance practice, which no longer gets to the bottom of things individually, but only applies what has been common practice for 20-30 years, which no longer questions further in research, no longer looks for new things, but only mixes together ready-made things like “convenience food” – into new hypotheses, new pseudo-knowledge.

But now I would rather return to the good old tree.

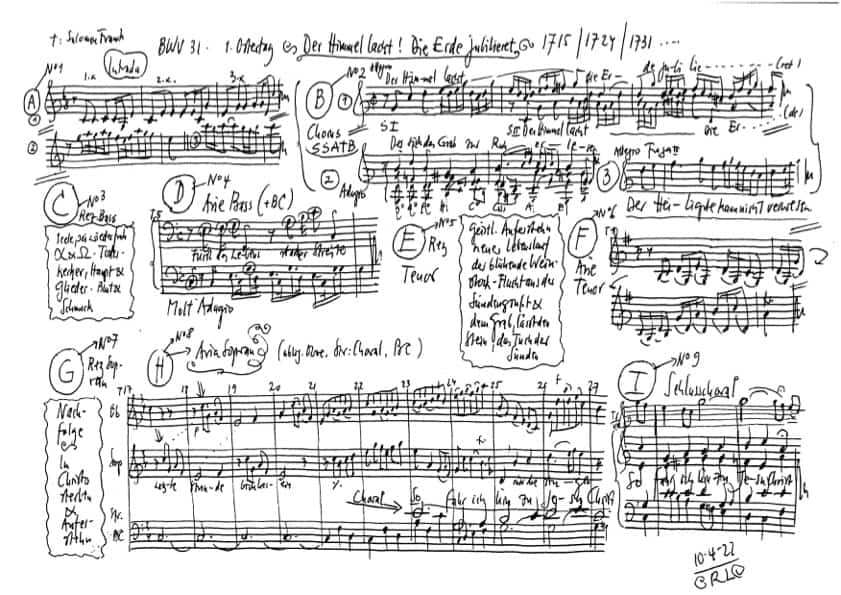

At the centre of the image of the tree trunk, for me, is the idea that any kind of performance practice should recognise. Bach’s “idea” of the work, his personal motivation as a church musician in the tradition of Protestant church music, but in addition also the own motivation of “his” text poet as well as the connection with the concrete liturgical reference to the respective Sunday or feast day. Seen in this picture, Bach’s first annual rings would be the first autograph score (or drafts of it), usually with corrections, which show us how the composer implements a concrete idea and what compositional difficulties there are to overcome. Further annual rings would then be: the performance parts with their entries on the instrumental scoring and on the arrangement of the parts, often specified more precisely here. And then, over time, there are further annual rings: Bach’s own arrangements, e.g. of the cantata “Der Himmel lacht! Die Erde jubilieret” (BWV 31), these are the changes in the woodwind instrumentation: the reduction of the 4-part (!) Weimar woodwind choir to then only a single oboe in his first Leipzig period …

A much later annual ring would then be a symphonic performance apparatus, which was also used for Bach cantatas in the late 19th and 20th centuries, in order to correspond to the respective sound of the time, including the adaptation of the voices to the respective instruments of the time. Like the annual rings of the tree, this development was initially almost always additive. More and more, fuller and fuller. But in each of these phases, Bach’s music has always been effective – despite all these new rings, one must always be clear about that.

Especially with the old Bach Complete Edition, whose initiators included quite a few composers of the time, the process of a successive return began in 1851; at first only in the musical text, in which no editor’s addition whatsoever was tolerated; the good old Bach tree thus provided orientation in the Romantic jungle in the middle of the 19th century (especially for such composers as Robert Schumann and Johannes Brahms). Then, only a good hundred years later, there was also a gradual return in sound, in the search for original sound instruments of Bach’s time and their authentic way of playing. So far, so familiar in Trogen!

This process of searching for traces of the original sound is also far from complete. A few examples: The so-called clarino blowing without auxiliary holes, still unknown in Bach’s time, is cultivated today only very exceptionally. And the chest organs so popular today are actually small flexible auxiliary constructions of the 20th century for concert use with changing tunings and changing concert venues. Regrettably, however, they are a testimony to the sound of an age in which the continuo group is fenced in, as it were, so that the upper voices can spread their flowery charm all the more airily. Performances with a large organ and its tonal differentiations should – in my opinion – be given more consideration. In my opinion, the continuo apparatus in particular, which Bach increasingly differentiated the longer he worked in Leipzig, such as the 16-foot contrabassoon in the last version of the St. John Passion BWV 245.5, should not be thinned out in favour of an overly upper-voice-heavy sound in the Italian concerto tradition. At the same time, stronger middle and lower voices lend Bach’s music a certain force, which, however, can hardly be heard in concerts today. This sound would probably be more in keeping with the French performance tradition, which shows a greater differentiation of the middle voices. This evening, by the way, we hear offshoots of this tradition in the Weimar string section with its two violas. At this time, Bach is still strongly influenced by this French tradition; for example, a greater variety of string instruments of different sizes would also correspond to this tradition, not just the standardised violins, violas and cellos, so to speak.

Let us return to the tree: it is also incumbent on us musicologists to look at the annual rings since their origin separately and, moreover, to clearly name the roots from which Bach’s music draws its strength and to expose them in a value-free way – and, of course, not to presume a damning judgement on the various “sounds of time”. In each case, they are based on a preceding tradition and are to be understood from within it. If you don’t have oboes da caccia, you’ll have to make do with English horns. Harpsichords also had to be rebuilt in the 20th century. And so on and so forth.

But a performance practice should never become entrenched, or figuratively speaking: The tree should also be allowed to continue to grow freely and not be pruned according to a pattern that is always the same. One pruned tree looks like the next. In the cantata concert, it happens that one cantata is often placed next to the other without any relationship, like a pruned tree, detached from the context, but accurately trimmed. And next to it in the concert stands the second and third trimmed cantata. Foreign bodies in the concert system, and the question is: how far should one go with the transplantation of trees? Do sacred cantatas really belong in modern concert practice in this way?

Yes, certainly, the good thing about pruning and “historically informed” performance practice is that the tree – freed from epiphytes, for example, which partly feed on the tree and take away its strength – stands freer after pruning. Bach’s music, to stay with the metaphor, becomes more airy and easier to hear through original sound ensembles.

And a pruned tree, as I know from my admittedly amateurish Leipzig allotment gardening practice, has to be pruned again and again. But: once you have started pruning, you must always bring it back into shape. After all, it is supposed to keep the same, man-made shape. This danger also exists when dealing with baroque music: that it is pruned until it can no longer unfold freely.

In my work on the new “Bach-Werke-Verzeichnis”, a task that only came to an end in May 2022 after twelve years of research and editorial work, it was rarely a question of concrete performance practice. After all, very many aspects of a musical performance were not notated by Bach; they have to be laboriously abstracted and are therefore not part of a catalogue raisonné. In the specifically Leipzig-oriented Bach basic research, we look at everything from the perspective of “sources”; these are above all written documents from Bach’s time and, beyond that, documents of Bach’s reception in the various centuries. And it is the original musical sources that we make available to all interested parties in the online portal “Bach digital”. This complete material is the basis for the new BWV3, for which we have once again looked at all available sources and questioned traditional views.

This is the ever new task that we continue to set ourselves in Leipzig, even after the completion of the “New Bach Edition”: We continue to collect all types of documents, we try to find new ones, we try to find out the context. Ultimately, we are trying to broaden the data base for further studies and analyses. What could sometimes be called fact-hoarding can stand on its own for the time being. In a fake news world, that is already a statement.

How can fact-finding be fruitfully combined with bringing music history to life, and especially source-based Bach research, using the example of BWV 31, the cantata for Easter Day 1? In the new BWV3, we try in particular to briefly describe the history of the work, to separate the specific Weimar layer – or the Weimar annual ring – from further Leipzig rings or layers. When does Bach rework this cantata and why? Now is not the place or time to go into many details. I would like to highlight only one aspect that seems particularly striking to me, the ars moriendi ending, which is remarkable for a cantata for Easter Day. Are there biographical references in the cantata to which the librettist and composer wanted or had to draw attention at Easter 1715 – my guiding question in view of my observation is that we have a unique selling point before us here: a festive cantata for Easter that does not conclude with Easter cheer but with an admonition to the listener to order the house.

Briefly on the external circumstances around 1715: it is Bach’s first cantata after the 27-year-old co-regent Prince Ernst August granted him a substantial increase on his concertmaster’s salary on 20 March. As a festive cantata, “Der Himmel lacht! Die Erde jubilieret” is unusually opulent in its scoring: In addition to the trumpets and timpani and the four-part string choir and the five-part vocal movement, there is also a four-part oboe choir – in the sonata, the opening chorus and the final chorale. Prince Ernst August himself may also have played the violin in the performance. (In any case, Johann Gottfried Walther writes that Ernst August often played in the court orchestra; after Bach’s departure for Köthen, the prince then completed an apprenticeship as a trumpeter. Representative festive music was a matter of concern to the prince, that much is clear).

Just a few figures on the presumed maximum size of the Weimar court orchestra at that time: there were about 16 musicians in regular pay: four violinists, a bassoonist, nine singers plus a Kapellmeister, a Vizekapellmeister and a Konzertmeister. If necessary, about five town musicians and a maximum of ten regimental oboists were called in, in addition to seven court trumpeters, who could also be used for other woodwind instruments, and a timpanist. In addition, there could be other servants who were also active in non-musical services at court. A remarkable apparatus.

The great festive Easter cheer unfolded in movements 1 and 2 contrasts in a peculiar way with the admonitions to “order one’s house” in the back part of the cantata (movements 7-9). What is this all about?

The young Prince Johann Ernst (nephew of the reigning Prince Wilhelm Ernst and brother of the aforementioned Ernst August), Bach’s pupil and a very gifted composer, as we know from several orchestral concerti, had been seriously ill since 1713 (“painful maladie” is what it says in the estate files; probably a tumour on his leg. Prayers for his recovery were published and, after a brief improvement, a prayer of thanksgiving on his return to Weimar from a cure). Behind Johann Ernst lay the famous cavalier tour in the summer of 1713 to the Netherlands, among other places, where Italian music was eagerly ordered for the Weimar court. As early as the summer of 1714, he set off with his mother for a fountain cure in Schwalbach (later to Wiesbaden), and he died in Frankfurt on 1 August 1715 at the age of only 18 – only four months after Easter (21-23 April).

The cantata could well have been written by the Weimar court poet Salomon Franck and the concertmaster Bach especially with this great sorrow in mind. At any rate, it would explain the marked darkening of the Easter cheer. According to another hypothesis, which also did not find its way into BWV3, Bach’s farewell greeting to the prince would have been the cantata “Ich hatte viel Bekümmernis” BWV 21, of which we know the third Sunday after Trinity as the day of performance, and that would have been in June 1714 immediately before his departure for the spa.

The fate of this young Weimar prince may have meant more to Bach than is known so far. For me, the preoccupation with this extraordinary Easter cantata “Der Himmel lacht! Die Erde jubilieret” now gives me cause to search for more here. But biographical references in Bach’s vocal music are – like the blossoms of a tree – extremely fleeting.

This text has been translated with DeepL (www.deepl.com).