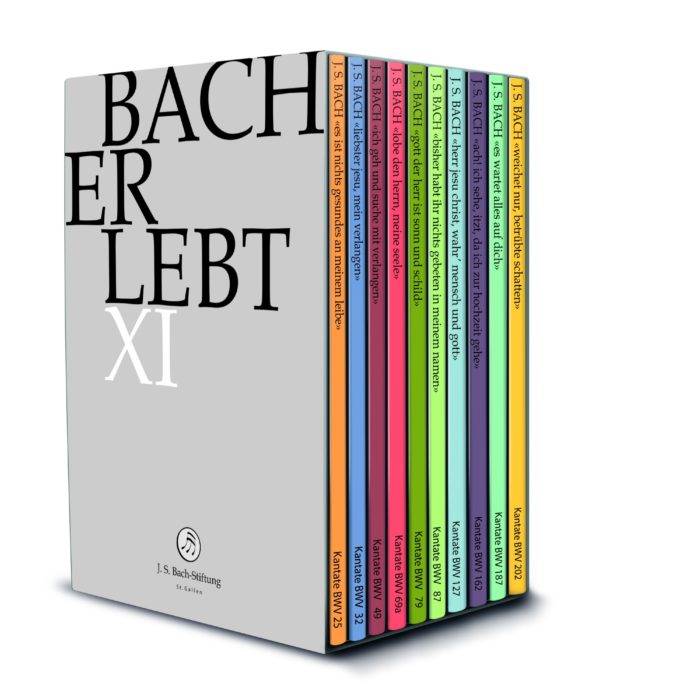

Liebster Jesu, mein Verlangen

BWV 032 // For the First Sunday after Epiphany

(Dearest Jesus, my desiring) for soprano and bass, vocal ensemble, oboe, strings and basso continuo

Would you like to enjoy our videos ad-free? Subscribe to YouTube Premium now...

Workshop

Reflective lecture

Orchestra

Conductor & cembalo

Rudolf Lutz

Violin

Renate Steinmann, Olivia Schenkel

Viola

Susanna Hefti

Violoncello

Daniel Rosin

Violone

Markus Bernhard

Oboe

Katharina Arfken

Organ

Nicola Cumer

Musical director & conductor

Rudolf Lutz

Workshop

Participants

Karl Graf, Rudolf Lutz

Reflective lecture

Speaker

Fabian Müller

Recording & editing

Recording date

20.01.2017

Recording location

Trogen AR (Schweiz) // Evangelische Kirche

Sound engineer

Stefan Ritzenthaler

Director

Meinrad Keel

Production manager

Johannes Widmer

Production

GALLUS MEDIA AG, Switzerland

Producer

J.S. Bach Foundation of St. Gallen, Switzerland

Librettist

Text

Georg Christian Lehms, 1711

Text No. 6

Paul Gerhardt, 1647

First performance

First Sunday after Epiphany,

13 January 1726

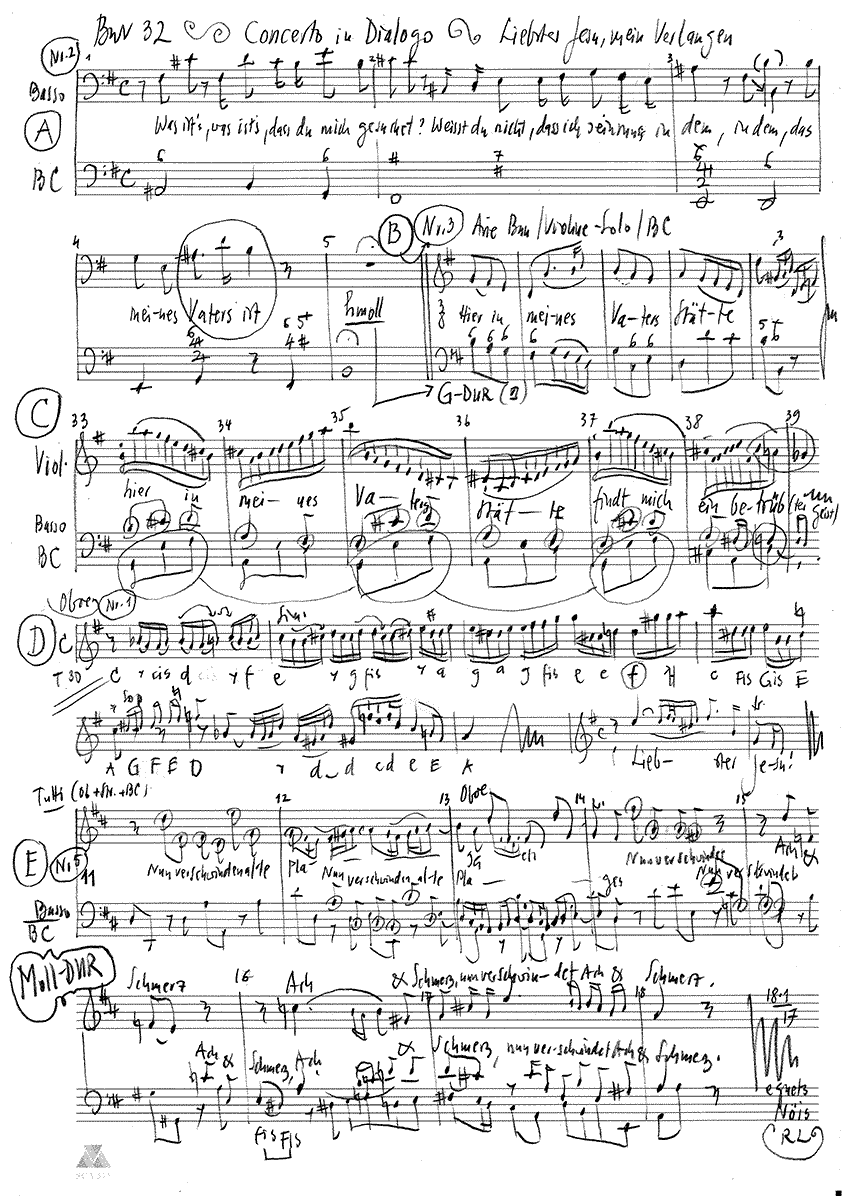

In-depth analysis

The reading for the First Sunday after Epiphany, taken from the Gospel of Luke, tells the story of the twelve-year-old Jesus’ visit to the temple after becoming separated from his parents in Jerusalem. This parable of loss and reunion was often employed as an analogy for the painful separation of the Saviour from his community of followers – felt all the more keenly after the closeness of the Christmas season. Although the cantata was composed in 1726 in Leipzig, its libretto by Georg Christoph Lehms and chamber-music scoring lend it elements of a cantata from Bach’s Weimar era.

The scoring for an ensemble of soloists immediately distances the introductory movement from any realist narrative concerning a group of people. Instead, the theme of searching is interpreted as the soul’s longing for the Saviour, and the entire cantata is thus set as a “concerto in dialogo” for soprano and bass. The oboe cantilena, written in the style of a concerto movement over piano e spiccato strings, establishes the tone for a setting in which the rests are at least as important as the notes, and in which it is no coincidence that the broken chords of the string accompaniment alternately ascend and descend. The key of E minor, with its noble sorrow and acute worry, is fitting for both the gospel story and the human hopes and fears so poignantly expressed in the gentle melismas of the soprano part.

With its vivid, questioning gesture of “Was ists?” (Why is it?), the bass recitative presents a short, pithy statement that melds the precociousness of the wise child with the gravitas of the bass register and emphatically pinpoints the church as the place to find healing.

In the aria, the fact that Jesus feels no anger but is instead touched by the efforts to discover him becomes audible, and the tender, transparent music celebrates the Saviour’s approachable nature. Over a gentle bass line, the solo violinist presents flowing embellished lines that seem to smile indulgently at technical difficulty, performing lightly as though with a silver mute. This leaves scope for the bass soloist to present his part in a measured style and address an individual rather than a large audience. In the middle section, the motives and modulations of the violin part grow in complexity – almost as though Jesus’ promise had invoked the transformative power of the holy spirit.

After outlining their positions, the soul and Jesus are united in an accompagnato recitative. A mysterious string accompaniment sets the scene for the soprano, whose opening line of “Ach heiliger und grosser Gott!” (Ah, holy and most mighty God) is akin to an act of devout deference. Jesus responds, however, with a summons to reject worldly concerns, tipping the conversation towards a test of faith. This is averted by the psalm paraphrase “Wie lieblich ist doch deine Wohnung, Herr, starker Zebaoth” (How lovely is, though, this thy dwelling, Lord, mighty Sabaoth). Here, the words ring in the longed-for meeting as equals, and the progression from fear to submission to soulful unity is paired with ever-freer singing and delicately rendered alternating lines in the string accompaniment.

The following duet, with its full ensemble sound and brazen dance-like phrases, employs a style that, in Bach’s oeuvre, stands for regained certainty. Here, the at times madcap movement resembles an orchestral suite setting in which the first violin deftly weaves its way around the vocal and oboe motifs. The descending leap of a sixth makes for a cheeky gesture suited to mischief of all sorts, thus allowing the lovers to jump merrily through puddles holding hands: “Ach und Schmerz” (Ah and woe) are nothing but a bygone memory, no longer a burden but a uniting experience.

Although Lehms’s libretto included no closing chorale, the closing hymn verse added in Leipzig rounds out the dialogue by taking the group – and by extension the congregation – into account. With the scoring for chamber ensemble, however, Paul Gerhardt’s verse set to the famous melody of “Freu dich sehr, o meine Seele” is more of an aria for four voices than a rousing church hymn. The ascending melody of the middle lines captures the singers’ energising joy (“Liebe mich und treib mich an” – Love me, too, and lead me on); it is akin to how we might feel when we see a happy couple – we take some of their joyful energy with us on our further journey.

Libretto

1. Arie (Sopran)

Liebster Jesu, mein Verlangen,

sage mir, wo find ich dich?

Soll ich dich so bald verlieren

und nicht ferner bei mir spüren?

Ach! mein Hort, erfreue mich,

laß dich höchst vergnügt umfangen.

2. Rezitativ (Bass)

»Was ists, daß du mich gesuchet? Weißt du nicht, daß ich

sein muß in dem, das meines Vaters ist?«

3. Arie (Bass)

Hier, in meines Vaters Stätte,

findt mich ein betrübter Geist.

Da kannst du mich sicher finden

und dein Herz mit mir verbinden,

weil dies meine Wohnung heißt.

4. Rezitativ (Dialog Sopran, Bass)

Sopran

Ach! heiliger und großer Gott,

so will ich mir

denn hier bei dir

beständig Trost und Hülfe suchen.

Bass

Wirst du den Erdentand verfluchen

und nur in diese Wohnung gehn,

so kannst du hier und dort bestehn.

Sopran

Wie lieblich ist doch deine Wohnung,

Herr, starker Zebaoth;

mein Geist verlangt

nach dem, was nur in deinem Hofe prangt.

Mein Leib und Seele freuet sich

in dem lebendgen Gott:

Ach! Jesu, meine Brust liebt dich nur ewiglich.

Bass

So kannst du glücklich sein,

wenn Herz und Geist

aus Liebe gegen mich entzündet heißt.

Sopran

Ach! dieses Wort, das itzo schon

mein Herz aus Babels Grenzen reißt,

faß ich mir andachtsvoll in meiner Seele ein.

5. Arie (Duett Sopran, Bass)

Nun verschwinden alle Plagen,

nun verschwindet Ach und Schmerz.

Sopran

Nun will ich nicht von dir lassen,

Bass

und ich dich auch stets umfassen.

Sopran

Nun vergnüget sich mein Herz,

Bass

und kann voller Freude sagen:

Sopran, Bass

Nun verschwinden alle Plagen,

nun verschwindet Ach und Schmerz!

6. Choral

Mein Gott, öffne mir die Pforten

solcher Gnad und Gütigkeit,

laß mich allzeit allerorten

schmecken deine Süßigkeit!

Liebe mich und treib mich an,

daß ich dich, so gut ich kann,

wiederum umfang und liebe

und ja nun nicht mehr betrübe.

Fabian Müller

Dialogue

A musical reflection on the Bach cantata “Liebster Jesu, mein Verlangen” (BWV 32)

It is a great risk to compose a musical reflection on such perfect music as Bach’s cantata Liebster Jesu, mein Verlangen (BWV 32). For how should one encounter such a coherent world in terms of content and music. A task that on the one hand pleased me very much, but on the other hand also instilled great respect in me. As an inner attitude to master this challenge, the best possible way seemed to me to be an intuitive, very personal approach.

The result is a dialogue between two instruments that very freely takes up the idea of the soul’s longing for the divine.

There is already a searching restlessness at the beginning, in the low notes of the violoncello. Later, in the course of the music, it sometimes takes on dramatic, almost desperate features. The heavenly answer lies, so to speak, in the quiet meditative sections in the middle and at the end of the piece, where a contemplative clarinet melody without beginning or end, accompanied by fine harmonics of the violoncello, symbolises the connection of the soul with God.

Apart from this very personal approach to the theme of the cantata, I found it attractive to refer to a few elements of Bach’s music. But it should not be superficial, but almost imperceptible and quiet, as if the wind were carrying fragments of music to our ears from far away, or like a distant memory.

Perhaps the audience perceived a little of this Bachian music – consciously or unconsciously – in my composition. It is above all these almost dance-like melodic motifs from the second aria which appear at times.

And it was precisely in this second aria that I also found another moment extremely fascinating, namely how Bach quite unexpectedly and suddenly colours the words “betrübter Geist” with a minor key. Perhaps a passage may also stand out in my music, around the middle, just before a quiet part begins, which recalls this particular moment.

It is a gift for me that I can now hear the piece a second time, in this beautiful room, where, if I remember correctly, I was last allowed to perform with Noldi Alder, who is also with us today, and the New Appenzell String Music Project. That was some years ago. I have been connected to Appenzell – not only musically – since my earliest youth and to this day.

It was also a special gift that I was given this task of contributing to the cantata performances of the St. Gallen Bach Foundation. And I would like to thank the Bach Foundation and all those behind this great project most sincerely.

This text has been translated with DeepL (www.deepl.com).