Ich elender Mensch, wer wird mich erlösen

BWV 048 // For the Nineteenth Sunday after Trinity

(A poor man am I; who will set me free) for alto and tenor, vocal ensemble, oboe I+II, bassoon, strings and continuo.

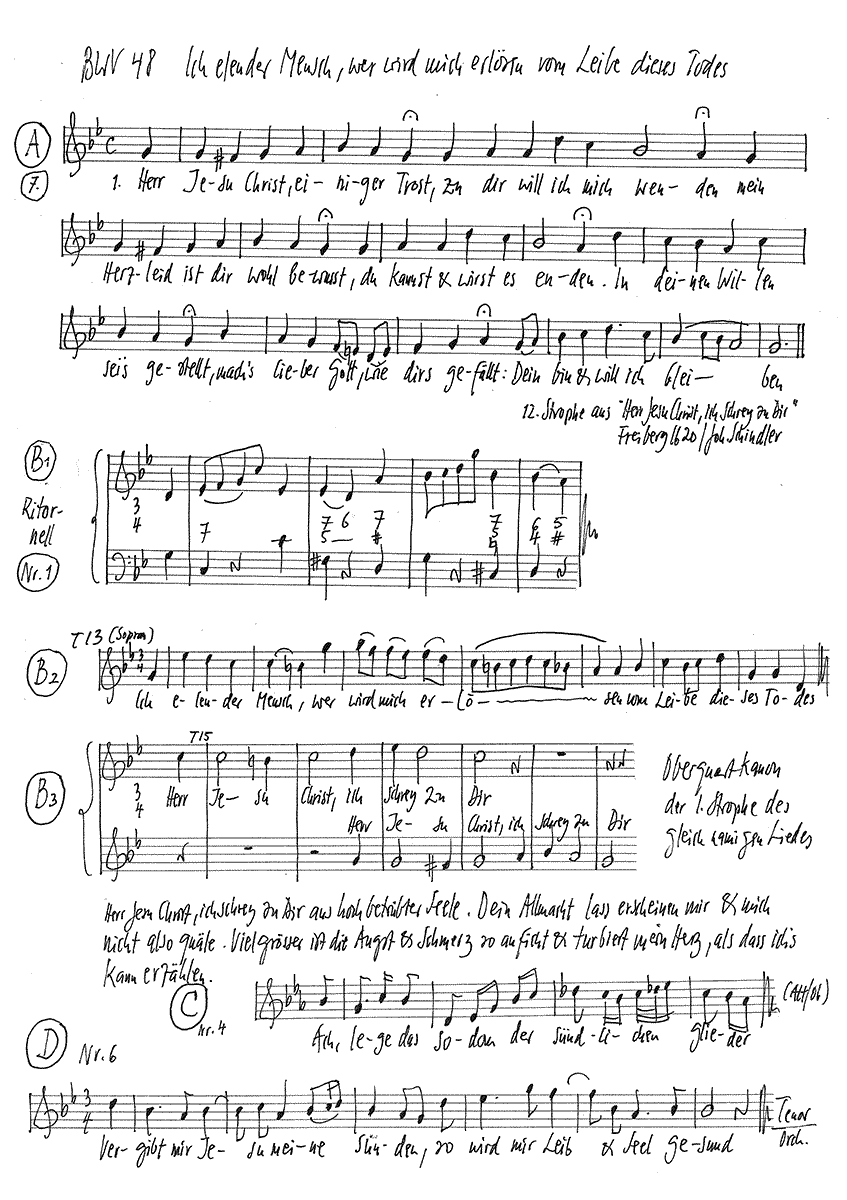

In the introductory chorus to cantata BWV 48, Bach lends the wretched words of Paul, “A poor man am I; who will set me free from the body of this dying?” a musical interpretation that reveals much about the composer’s associative reading of the Bible. The movement opens with a bittersweet ritornello by the strings, which, underpinned by a sparse double bass line, is more a subdued confession of sorrow than a heated expression of despair. Indeed, it is precisely the lack of terrifying rhetoric that heightens the impact of the movement: although the text speaks of personal apprehension, it is not the acute sin of the individual that is at issue but the fundamental depravity of humankind under the law of God, a message that is expressed in its full rigour by the setting’s archaic motet style and the masterful double canon for the vocalists and obbligato instruments.

Would you like to enjoy our videos ad-free? Subscribe to YouTube Premium now...

Workshop

Reflective lecture

Choir

Soprano

Guro Hjemli, Susanne Frei, Jennifer Rudin

Alto

Antonia Frey, Jan Börner, Lea Scherer

Tenor

Nicolas Savoy, Manuel Gerber, Marcel Fässler

Bass

Chasper Mani, Matthias Ebner, Othmar Sturm

Orchestra

Conductor

Rudolf Lutz

Violin

Renate Steinmann, Livia Wiersich

Viola

Joanna Bilger

Violoncello

Martin Zeller

Violone

Iris Finkbeiner

Oboe

Kerstin Kramp, Meike Gueldenhaupt

Bassoon

Susann Landert

Organ

Ives Bilger

Musical director & conductor

Rudolf Lutz

Workshop

Participants

Karl Graf, Rudolf Lutz

Reflective lecture

Speaker

Ursula Pia Jauch

Recording & editing

Recording date

10/20/2006

Recording location

Trogen

Sound engineer

Stefan Ritzenthaler

Director

Meinrad Keel

Production manager

Johannes Widmer

Production

GALLUS MEDIA AG, Switzerland

Producer

J.S. Bach Foundation of St. Gallen, Switzerland

Librettist

Text

Poet unknown

First performance

Ninteenth Sunday after Trinity,

3 October 1723, Leipzig

In-depth analysis

In the introductory chorus to cantata BWV 48, Bach lends the wretched words of Paul, “A poor man am I; who will set me free from the body of this dying?” a musical interpretation that reveals much about the composer’s associative reading of the Bible. The movement opens with a bittersweet ritornello by the strings, which, underpinned by a sparse double bass line, is more a subdued confession of sorrow than a heated expression of despair. Indeed, it is precisely the lack of terrifying rhetoric that heightens the impact of the movement: although the text speaks of personal apprehension, it is not the acute sin of the individual that is at issue but the fundamental depravity of humankind under the law of God, a message that is expressed in its full rigour by the setting’s archaic motet style and the masterful double canon for the vocalists and obbligato instruments. Respite from this repressive music is offered solely by the chorale melody – intoned in canon by the winds – “Lord Jesus Christ, I cry to thee”, whose wordless presence, coupled with the helplessly questioning conclusion of the movement, throws into relief the seemingly insurmountable distance between mortals and their Saviour.

This is followed by an impassioned alto recitative replete with despair: the depravity of human nature and its poisoning by the burden of sin renders the whole world a “house of death and sickness”. In this passage, Bach presents a series of painful interpretations in which harmonic severity, falling dissonances and effective pauses converge to pronounce a truly devastating verdict. It is difficult to imagine that the composer, ever open to new ideas, did not draw upon his exposure to the death scenes so popular in early baroque opera.

The following chorale represents a return to a familiar form of solace and congregational unity; its inclusion allows for a moment of distanced reflection, an effect also achieved by the hymn verses inserted in the Passion compositions. Nevertheless, its bold, otherworldly setting – especially the line “Continue on, Refine me there” – ensures that the chorale remains embedded in the emotional drama of the cantata. Indeed, Bach lent the chorale such an exquisite harmonic language that it goes beyond all collective tradition to express an individual acceptance of penance and suffering in this world.

With a distinctive oboe obbligato, the alto aria echoes the sad and gentle character of the introductory chorus, while the Old-Testament metaphor of Sodom couples personal sin and weakness, thus underscoring this familiar trope of baroque Bible interpretation. The individual effort required to transform the soul of the believer into the holy Zion is, however, made abundantly clear in the childlike simplicity of Bach’s musical gesture. As the ensuing tenor recitative succinctly reveals, this transformation is achieved with the helping hand of the Saviour, who can not only raise the dead, but also revive and strengthen those who are dead of soul.

With such solace in sight, the tenor is buoyed in the following aria to a spirit of generous character and defiant determination that could hardly have been predicted at the beginning of the cantata. In this sacred minuet with its echoes of a pithy Schemelli hymn, gratitude and humility are suspended in miraculous balance over a subdued orchestral fundament.

The closing chorale “Lord Jesus Christ, my only help” resolutely upholds this aura of cautious yet pious hope. After overcoming their crisis of faith, the “weak in spirit” can now (unlike in the opening chorus) join in the singing, but the chorale is an audible reminder that such participation requires unceasing insight into the unfathomable workings of the Almighty.

Libretto

1. Chor

«Ich elender Mensch, wer wird mich erlösen vom Leibe

dieses Todes?»

2. Rezitativ (Alt)

O Schmerz, o Elend, so mich trifft,

indem der Sünden Gift

bei mir in Brust und Adern wütet:

Die Welt wird mir ein Siech- und Sterbehaus,

der Leib muß seine Plagen

bis zu dem Grabe mit sich tragen.

Allein die Seele fühlet

den stärksten Gift,

damit sie angestecket;

drum, wenn der Schmerz den Leib des Todes trifft,

wenn ihr der Kreuzkelch bitter schmecket,

so treibt er ihr ein brünstig Seufzen aus

3. Choral

Solls ja so sein,

daß Straf und Pein

auf Sünde folgen müssen,

so fahr hie fort

und schone dort

und laß mich hie wohl büßen.

4. Arie (Alt)

Ach lege das Sodom der sündlichen Glieder,

wofern es dein Wille, zerstöret darnieder!

Nur schone der Seelen und mache sie rein,

um vor dich ein heiliges Zion zu sein.

5. Rezitativ (Tenor)

Hier aber tut des Heilands Hand

auch unter denen Toten Wunder.

Scheint deine Seele gleich erstorben,

der Leib geschwächt und ganz verdorben,

doch wird uns Jesu Kraft bekannt.

Er weiß im geistlich Schwachen

den Leib gesund, die Seele stark zu machen.

6. Arie (Tenor)

Vergibt mir Jesus meine Sünden,

so wird mir Leib und Seel gesund.

Er kann die Toten lebend machen

und zeigt sich kräftig in den Schwachen;

er hält den längst geschloßnen Bund,

daß wir im Glauben Hilfe finden.

7. Choral

Herr Jesu Christ, einiger Trost,

zu dir will ich mich wenden;

mein Herzleid ist dir wohl bewußt,

du kannst und wirst es enden.

In deinen Willen seis gestellt,

machs, lieber Gott, wie dirs gefällt:

Dein bin und will ich bleiben.

Ursula Pia Jauch

“Summer religion or winter faith? Misery or Eros?”

Reflections of a defrocked Catholic at the beginning of the homeless 21st century, seconded by Heinrich Heine, Georg Christoph Lichtenberg and Blaise Pascal, starting with Johann Sebastian Bach, the divine musician, who else.

In 1828, in his “Reisebilder”, Heinrich Heine describes his journey from Munich to Genoa. In Chapter XV, he has arrived in Trento, Italy. And as always, the German, who was born a Jew in 1797 and who was baptised a Protestant in 1825, is drawn to where? To a Catholic church, if possible to a cathedral. A strange paradox: there is probably no poet of the German tongue who is as sharp-tongued towards all things Christian – both Catholic and Protestant – as Heinrich Heine, although there is almost nowhere he prefers to be than in the most imposing Catholic cathedral possible. One can – allow me this digression – formulate a Heine rule of thumb of heresy, so to speak, which reads: the higher the columns of the Gothic cathedral visited in each case, the more powerful Heine’s religious mockery. “A cathedral was never big enough for me; my soul with its old titanic prayer always strove higher than the Gothic pillars and always wanted to break out through the roof,” he once commented to himself. The practised reader knows that such a Heine prelude will be followed by a corresponding religious recklessness. Indeed: once, still in Germany and in view of the imposing Cologne Cathedral, Heine feels inspired to illustrate the relationship between body and soul, which is admittedly ticklish in Catholic dogmatics, with the following thought: “Who knows whether the soul of Pope Gregory VII does not sit in the body of a Grand Turk and feel more comfortable under a thousand fondling little women’s hands than it once did in its purple celibate frock?”

So no one will be surprised that the Roman censors in Italy were not amused by Heine’s prose. But that did not bother Heine at all. And it didn’t stop him from travelling to Italy himself. And so, after this little diversions, we are now where we were before: namely, in the hot summer of 1828, at Heine’s arrival in Trento. Heine marches straight to Trento Cathedral, pushes aside the green-silk curtain and – we are in Chapter XV of Part Three of “Reisebilder” – comments as follows:

“Truly, such a cathedral with its subdued light and its wafting coolness is a pleasant place to stay when outside there is glaring sunshine and oppressive heat. We have no idea of this in our Protestant northern Germany, where the churches are not built so comfortably and the light shoots in so boldly through the unpainted panes of reason and even the cool sermons do not protect us enough from the heat. Say what you will, Catholicism is a good summer religion. It is good to lie on the benches of these old cathedrals, one enjoys the cool devotion there, a holy dolce farniente, one prays and dreams and sins in one’s thoughts, the Madonnas nod so forgivingly from their niches, feminine-minded, they even forgive when one has interwoven their own fair features into one’s sinful thoughts, and to top it all off, in every corner there is a brown emergency chair of conscience where one can get rid of one’s sins.”

Catholicism as a cooling summer religion

Heine’s “Reisebilder” appeared in 1830. Six years later, the Index Congregation in Rome noticed that a German (who was also a Protestant and a baptised Jew) had spoken with great derision about the cooling effect of Catholicism as a refreshing summer religion and about the fact that it was quite comfortable to sin in Catholicism, since the confessional for the spiritual urgency of the Catholic was just as infallible as another chair for the urgency of the rest of the body. Heine’s “Reisebilder” were therefore put on the Index in 1836. And until 1966, a devout Catholic was only allowed to read “Reisebilder” under penalty of excommunication. Which is quite a pity, because there is – the remark may be allowed – no equally beautiful and frivolous demonstration in German literature of the comforts of the Catholic faith in particular. A small dramaturgical remark: there are three reasons why I have so far spoken so extensively about Heinrich Heine and his remarkably intimate relationship to Catholicism, instead of about Johann Sebastian Bach and the trials of conscience of Protestantism, the misery of man and the “Sodom of the sinful members”, as it is so drastically called in the first aria of the cantata BWV 48:

Firstly, Heinrich Heine died on 17 February 1856, 150 years ago, a fact that has been almost completely forgotten in the Mozart Year 2006. I also regret this forgetting because, secondly, there is hardly another poet who, despite all the provocative by-, in-between and undertones, has written such a friendly, literary advertising campaign for the sensual pleasures that Catholicism and faith in general offer its adherents. Cue summer and sinful dolcefarniente: Allow me – as a defrocked Catholic – a personal reminiscence: I myself grew up in southern German Catholicism and experienced tangible childlike delights in the Birnau monastery church, i.e. in the most beautiful southern German baroque: the sweetness of a Sunday morning drenched in incense under pastel-coloured and wonderfully lascivious ceiling frescoes, in the design of which the artists had outdone each other; in the central nave, the frivolous honey licker could be admired, he too a thoroughly physical little fellow who, with his quiver of honey, resembled Cupid more than a sexless angel. And those who boldly positioned themselves in the right place in front of the altar could immediately mount themselves in the ceiling fresco; in the middle of all the saints up there. For a cheeky painter mounted a small mirror to hold in the little hands of a putto, and ergo one found oneself not at all in the earthly dust, but also up there in the heights, among all the angelic beings. And when a good organist played Bach’s Toccata and Fugue with powerful registers on a beautiful Sunday morning, when the incense was steaming and the putti were blinking at each other, then heaven was indeed populated by angels and God-like beings and one intuitively understood that it was something very great, beautiful and happy to be able to be in this world.

That the greatness of Bach’s music was, so to speak, representative of the greatness of what could not be expressed in words was also understood at that time. But it was precisely this – Bach’s music as a vehicle and vector for man’s ability, given by God or whomever, to experience the world through the senses in all its unbelievable diversity – that Heine, whom I have followed so far like a church dog to its preacher, unfortunately and thirdly, failed to grasp.

For in Chapter XIX of “Reisebilder”, Heine, after praising Italian music and above all Rossini’s “Barbiere di Seviglia” to the skies, notes the following: “The despisers of Italian music, who also break the baton of this genre, will one day not escape their well-deserved punishment in hell and will perhaps be condemned to listen to nothing but fugues by Sebastian Bach throughout eternity.

That is sharp stuff indeed. Here, it is not only time, but downright morally appropriate, to finally turn away from Heine. Just imagine the agony a sensitive person suffers when he is not even allowed to hear anything in hell but already here on earth but Rossini’s … Barbiere. Imagine how irritated the soul and hearing would be if one had to listen, say, only once for three hours in a row to the chattering arias of Doctor Bartolo. Heine, who otherwise had no lack of a sense of transcendence, made something like a plea for modern entertainment debility. But it is not at all rare for someone to find themselves in good and higher spheres after three hours of Bach fugues.

Incidentally, it is not only Heine who distances himself from Bach. In 1953, a good 120 years after Heine, the Basel theologian Karl Barth said: “When the angels make music before the Lord God, they play Bach; when they are among themselves, they play Mozart”; a bon mot that was quoted surprisingly often in the Mozart Year 2006. What Karl Barth, who was a great admirer of Bach, really wanted to say with this, however, has so far remained unexplained. And one could, if one wished, comment on the whole thing with a little sentence from Franz Grillparzer’s “Poor Minstrel”: “They play Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart and Sebastian Bach, but nobody plays God.

Does God play? Does God speak?

Does Bach play the dear God? Or rather: Does he make God – and if so, how? – to speak? The text of the cantata we have heard begins strangely and plaintively, as if existence, quite contrary to the sensual delights of Catholicism described earlier, knew only pain, misery, sin and death. “I wretched man / Who will deliver me from the body of this death?” It is much easier for you to have felt as I did; listening to this cantata: Not only does the music hit us directly with its lamentation in a deeply sensitive place of the soul, but also the text: No one can remain cool, modern and detached here. It is almost as if Bach – who for us has almost frozen into a monument in the distance of the past and of veneration – were himself speaking to us: “I wretched man, who will deliver me …” Whoever surrenders to this cantata – one can probably not put it any other way than with this verb originating from the erotic vocabulary – will no longer be able to separate in sensual perception between the text and its embedding in the powerful, erotic linguistic force of the music; for the latter basically always hits us with greater intensity than that of everyday language spoken with words. Music and text suggest to us that we are a unity; an aesthetic Gesamtkunstwerk has, so to speak, dissolved us as rational beings; we no longer hear arguments, but are under the spell of a suggestion. Bach himself seems to be speaking to us, in the music as well as in the text: Of “the poison of sins”, of the world as a “wretched and dying house”, of the “plagues that the body must carry with it to the grave”.

A silver glance back to Bach

But whether it really happened that way is open to doubt. Let us take a biographical look at Bach’s life: from December 1717, Bach was chamber music director to Prince Leopold of Anhalt-Köthen. This would probably have been a dream job and a job for life, for the young prince is musically sensitive. What’s more: he’s not a haven for savings either. The court orchestra sometimes consists of 17 musicians of outstanding quality. And the quality of the instruments is not spared either. But then, in 1720, comes a year of fate and upheaval: in the summer of 1720, Bach’s first wife Maria Barbara dies, and in December Bach marries his second wife, the soprano Anna Magdalena Wilcke, who works at the Köthen court. Also in 1720, however, the relationship between Leopold von Anhalt-Köthen and Bach cooled noticeably. Ergo: from 1720 to 1723 Bach is basically looking for a job. And Bach only gets the new position as Thomaskantor in Leipzig at the second attempt, and even then only as a “third choice”; the Leipzigers’ original preferred candidate would have been Georg Philipp Telemann, but he declined for salary reasons. And it is something of a coincidence that Bach, as the last on Leipzig’s list of candidates, is offered the post after all.

In May 1723, Bach took up his post as Thomaskantor and Leipzig music director. It may be said here, however, that when God gives someone such an office, he must at the same time give him not only the intellect but also almost superhuman powers to do so. Bach is responsible for the music of the four main churches as well as for all music lessons at the Thomas School. And above all: a cantata had to be performed every Sunday and public holiday. Immediately after his appointment, Bach had to start composing cantatas at full speed, so to speak. On average, a cantata was composed every week, including the cantata “Ich elender Mensch, wer wird mich erlösen” (I am a wretched man, who will redeem me), which today is number 48 of the BWV. The cantata text, however, which seems to fit so seamlessly into the music, comes from a text arranger whose name has been lost in the traces of history. Bach himself, therefore, left the text to a skilled worker, so to speak – and he followed quite conventionally, first of all, the liturgical division of the church year: The 19th Sunday after Trinity, the feast of the Trinity, includes the beginning of the 9th chapter of the Gospel of Matthew, which tells of the miraculous healing of a paralytic or gout-ridden man.

Man: a being between miracle and trauma

It is quite astonishing what the unknown librettist does with the actually joyful message of the miraculous healing of the sick: where the Gospel text tells of the healing of the sick in rather matter-of-fact words – if a miracle can be a “matter” at all – the librettist transposes this joyful event, intensified by several dramatic chords, into a profound psychological affair that calls the darkest sides of human existence by name and leaves out no register with which the misery of human existence could be coloured even more blackly. The beginning and end of the first recitative are a masterpiece in the art of psychological punishment – “Oh pain, O misery, so me hit / by the sins’ poison / raging in my chest and veins” – and at the end of this first recitative it is even a “brünstig Seufzen” (“fervent sigh”) that the sinful body emits in the pain of death. The language of the text arranger is of a sensuality, yes, of an ardour, that is negative but can be grasped with both hands. The sins “rage” in this body just as God Eros raged before. And the fact that this sinful body sinned above all in the slippery region around the sixth commandment is not concealed at all. It is about the “Sodom of sinful limbs”, and man of the early 18th century is also a tremendous epicure, that is: a sinner in the flesh. But in contrast to the permanently sexualised man of the 21st century, for whom sexuality has meanwhile soon become a virtual affair without a guilty conscience and basically also without interpersonal contact and thus also without the danger of disease – in contrast, therefore, to this, so to speak, mentally aseptic man of the 21st century, who no longer has an intact heaven and certainly no intact faith above his head, the man of the early 18th century is still thoroughly mentally traumatisable. And this is what the cantata text builds on; this is, so to speak – allow me to use this word – its working capital. For where a true catharsis is to take place, that is, a purification that leads across the abyss to salvation and redemption, the fear of sin and damnation must be drastic and not as venial as it was with Heine, for example, in his beautiful and edifying Catholic summer religion.

Recently, in Strasbourg, in the Musée des Beaux-Arts, I happened to come across a painting by an unknown master, who has put this physical sin terror of the 17th century almost more vividly into the picture than the cantata poet did with words: In large format, at 1 metre 50 x 90 cm, a naked couple is depicted. And where in the course of our iconographic training we have become accustomed to these beautiful and paradisiacal Adam and Eve depictions, for example from the hand of Lucas Cranach, which look at us sweetly, naked and discreetly veiled in the sensitive areas, we see something quite different in the syphilis artist of Strasbourg: an emaciated and almost toothless man and a scrawny woman whose breasts hang down like empty sacks. The two are still alive, but slippery snakes and large worms are coming out of large holes in their yellow bodies, excrement flies are already sitting in the swarms. And a ghastly toad has attached itself to the woman’s labia, which have been stretched out excessively by use – the painter really does not impose any taboo on himself. We of today may look at the painting with our detached reason and analyse it expertly: In panel painting from the 10th to the 17th century, the toad stands as a symbolic animal for the mortal sin of lust, which, by the way, the unlearned contemporary of the 16th, 17th or 18th century still knew. And he probably also knew that the beginning of the cantata libretto BWV 48 – that is, the verse “Ich elender Mensch, wer wird mich erlösen vom Leibe dieses Todes?” – is a verse from the 7th chapter of Paul’s letter to the Romans.

But what else do we know today? Our late-modern natural sciences have pretty much radically abolished the soul, symbolic animals, sins, mortal sins and thus probably almost everything transcendent. A text like that of the cantata BWV 48 with its metaphors of sin, pain and misery can, so to speak, only be read and understood historically. We would perhaps still like to be “redeemed” from our time problems, or again, especially in the present day; we would perhaps like to have an intact heaven above us again. But our matter-of-fact time, our busy hurry and our scientific curiosity have not left us with many animate beings in the beyond of pure facts.

The unhappy message of molecular biology

And who lived or lives better now? The conscience-stricken Leipzig Thomas churchgoer in October 1723? Georg Christoph Lichtenberg, who formulated in 1782: “And I thankʼ it a thousand times to the dear God that he has let me become an atheist”? Heine with his supposedly secular Rossini faith? The contemporary Protestant? The late Catholics who try to retain the aesthetic appeal of the religious even with Bach’s cantatas? Or the metaphysically and religiously completely naked natural scientist of the 21st century who has made it his secular credo that everything man does and everything that happens in him is only a switching power of his brain? That human freedom – including, by the way, that of believing in a God or in the wondrous findings of today’s brain research; for that, too, is as yet no more than a belief – is a somewhat stupid or at least romantic illusion of those contemporaries who have not yet fully grasped the unhappy message of modern molecular biology? So who lives better? The one who believes or the one who does not believe? Blaise Pascal, the 17th century philosopher, answered this question with what has since become known as “Pascal’s wager”: Pascal argues that it is always a better “wager” to believe in God because the peace of mind and the value of expectation that can already be achieved by believing in a God in this life is always greater than in the life of an unbeliever whose world is without transcendence and hope.

This Pascal’s wager could also be applied to love – we can also believe in it or not. And perhaps those who believe in it will fare a little better in life than those who do not believe in love or who – as the unknown librettist of BWV 48 has shown us – only know the sinful side of the flesh: after all, the first chorale says quite unquestioningly, as if it were a mathematical axiom: “Shall it be so / that punishment and chastisement / must follow sin.” And the fact that in German the little word “müssen” (have to) rhymes so well with the big word “büssen” (atone) has probably caused more bad conscience in the course of German social history than all the beautiful love poetry of the High Middle Ages for erotic pleasure.

God Cupid as a stowaway

Heine, at any rate, who was not a bad man, has left us, despite his mockery, a neat summer religion that can sometimes still edify us on cooler winter evenings. I am thinking, for instance, of one of his late love poems, which has Cupid as its theme:

“We drove alone in the dark

In a dark mail coach all night;

We rested each other’s hearts,

We joked and laughed.

And when day came in the morning,

My child, how we marvelled!

For between us sat Cupid,

As a stowaway.”

Cupid, freedom, justice, redemption, consolation or even the great and mysterious vocabulary of God: all these hermeneutic heavyweights are suitable as stowaways in our otherwise sober and busy century. Anyone who can believe in something – Bach would probably agree with Pascal – has Sunday built back into his existence, even in our secular times. Whether it is now the 19th Sunday after Trinity or the coming Sunday, that plays a secondary role. Perhaps even the defroqued and sober contemporary of the 21st century will go to Birnau, to the baroque church, on such a Sunday and take a look at these little putti and cupids, which stand for earthly happiness, but which somehow also refer to a benevolent supernatural guardian angel.

Literature

– Heinrich Heine, Reisebilder. Complete Poems. Both in: Sämtliche Schriften.

– Six volumes, ed. by Klaus Briegleb, Hanser, Munich 1968-76

– Georg Christoph Lichtenberg, Aphorismen und andere Sudeleien, Reclam Verlag, Ditzingen 2003

This text has been translated with DeepL (www.deepl.com).