Ich armer Mensch, ich Sündenknecht

BWV 055 // For the Twenty-second Sunday after Trinity

(I, wretched man, I, slave to sin) for tenor, vocal ensemble, transverse flute, oboe d‘amore, strings and continuo

Would you like to enjoy our videos ad-free? Subscribe to YouTube Premium now...

Workshop

Reflective lecture

Soloists

Tenor

Bernhard Berchtold

Choir

Soprano

Guro Hjemli

Alto

Antonia Frey

Bass

William Wood

Orchestra

Conductor

Rudolf Lutz

Violin

Renate Steinmann, Yuko Ishikawa

Viola

Susanna Hefti

Violoncello

Martin Zeller

Violone

Iris Finkbeiner

Oboe d’amore

Ingo Müller

Bassoon

Susann Landert

Transverse flute

Claire Genewein

Organ

Rudolf Lutz

Musical director & conductor

Rudolf Lutz

Workshop

Participants

Karl Graf, Rudolf Lutz

Reflective lecture

Speaker

Urs Schoettli

Recording & editing

Recording date

11/18/2011

Recording location

Trogen

Sound engineer

Stefan Ritzenthaler

Director

Meinrad Keel

Production manager

Johannes Widmer

Production

GALLUS MEDIA AG, Switzerland

Producer

J.S. Bach Foundation of St. Gallen, Switzerland

Librettist

Text No. 1–4

Unknown author

Text No. 5

John Rist, 1642

First performance

Twenty-second Sunday after Trinity,

17 November 1726

In-depth analysis

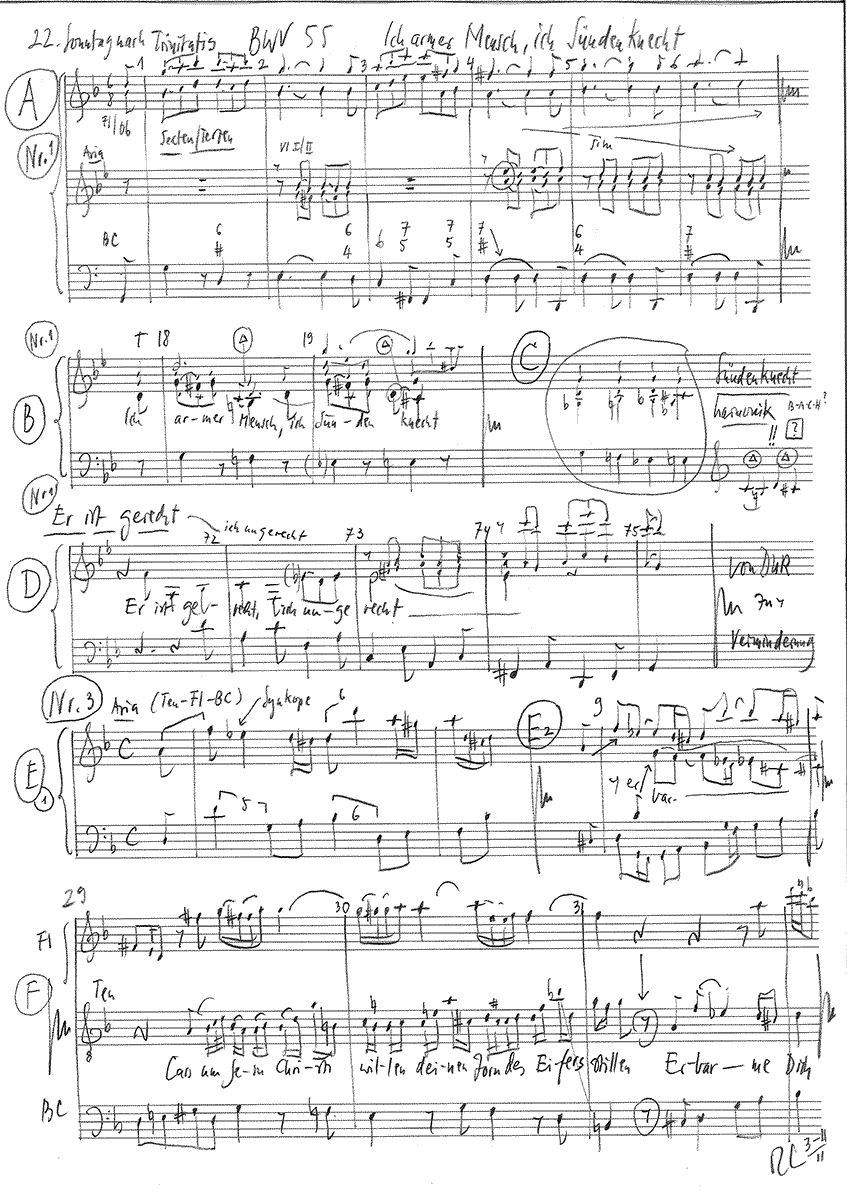

Cantata BWV 55 “Ich armer Mensch, ich Sündenknecht” (I, wretched man, I, slave to sin), one of Bach’s rare solo cantatas, was composed in 1726, a year in which Bach experimented more with his ensemble scoring. This tendency appears to have been particularly inspired by the poetic libretti of Christoph Birkmann, a student of theology in Leipzig and later a clergyman in Nuremberg, whom scholars have only recently identified as a librettist. The original score alternates between draft notation and quasi-fair copy, suggesting that only the first two movements were newly composed and that movements three and four, and perhaps also the closing chorale, were adapted from an earlier composition.

The introductory aria makes effective use of the exquisite instrumentation, which features a woodwind duo of transverse flute and oboe d’amore as well as a pair of violins (with no supporting viola parts). Here, the ongoing exchange of roles between the two duos imbues the setting with a fragile elegance and distinctive lightness, while the tense phrases of the vocalist exude less a heroic tone than a noble sense of remorse. Because the libretto provides for a repeat of the opening statement (“I, wretched man, I, slave to sin”) as the closing line of a two-part aria, Bach was inspired to employ a modified-reprise form with an extended coda.

The second movement, a recitative, is akin to a personal indictment of one’s own wrongful deeds. In this setting, the visions of escape and the self-recriminations (“Scheusal” – wicked me) are reminiscent of Peter’s penitence, thus lending weight to Andreas Glöckner’s theory that some of the cantata movements were related to a lost Passion written in 1717 during Bach’s Weimar period.

The following movement would certainly befit such a work: in the “Erbarme dich” (Have mercy) aria, the intermittent, meandering flute line can barely brighten this bleak D-minor trio that is dominated by a laconic bass line. Chromatic tones and constant descending figures magnify the penitent character of this aria, which resembles a prayer proffered in a moment of utter abandonment.

Although the following recitative, an accompagnato setting with strings, reiterates the “Erbarme dich” statement of the previous aria, it nonetheless finds consolation in the selfless suffering of Christ: thanks to his sacrifice, the faithful soul, too, can be spared heavenly judgement and embark on the path to mercy. Nevertheless, the notion that the remorseful, praying soul must remain mindful of the pain of Christ’s sacrifice is made manifest in the edgy accompaniment, whose severity is sustained until the comforting tones of the final bars.

For this state of the soul, there is hardly a closing chorale more fitting than Johann Rist’s “Bin ich gleich von dir gewichen, stell ich mich doch wieder ein” (Though I now from thee have fallen, I will come again to thee), a verse that also features prominently in the St Matthew Passion. Set by Bach with inimitable tenderness, this movement underscores the Passion-like character of a cantata that is highly unconventional in its combination of movements and motivic conception.

Libretto

1. Arie

Ich armer Mensch, ich Sündenknecht,

ich geh vor Gottes Angesichte

mit Furcht und Zittern zum Gerichte.

Er ist gerecht, ich ungerecht,

ich armer Mensch, ich Sündenknecht!

2. Rezitativ

Ich habe wider Gott gehandelt

und bin demselben Pfad,

den er mir vorgeschrieben hat,

nicht nachgewandelt.

Wohin? Soll ich der Morgenröte Flügel

zu meiner Flucht erkiesen,

die mich zum letzten Meere wiesen,

so wird mich doch die Hand des Allerhöchsten finden

und mir die Sündenrute binden.

Ach ja!

wenn gleich die Höll ein Bette

vor mich und meine Sünden hätte,

so wäre doch der Grimm des Höchsten da.

Die Erde schützt mich nicht,

sie droht, mich Scheusal zu verschlingen;

und will ich mich zum Himmel schwingen,

da wohnet Gott, der mir das Urteil spricht.

3. Arie*

Erbarme dich,

laß die Tränen dich erweichen,

laß sie dir zu Herzen reichen,

erbarme dich!

Erbarme dich,

laß um Jesu Christi willen

deinen Zorn des Eifers stillen,

erbarme dich!

*Jüngere Fassung der Originalpartitur

4. Rezitativ*

Erbarme dich!

Jedoch nun tröst ich mich,

ich will nicht für Gerichte stehen

und lieber vor dem Gnadenthron

zu meinem frommen Vater gehen.

Ich halt ihm seinen Sohn,

sein Leiden, sein Erlösen für,

wie er für meine Schuld

bezahlet und genung getan,

und bitt ihn um Geduld,

hinfüro will ich’s nicht mehr tun.

So nimmt mich Gott zu Gnaden wieder an.

*Jüngere Fassung

5. Choral

Bin ich gleich von dir gewichen,

stell ich mich doch wieder ein;

hat uns doch dein Sohn verglichen

durch sein Angst und Todespein.

Ich verleugne nicht die Schuld,

aber deine Gnad und Huld

ist viel größer als die Sünde,

die ich stets bei mir befinde.

Urs Schoettli

“Asia’s religions know no original sin”.

The cantata “Ich armer Mensch, ich Sündenknecht” in cultural comparison.

“Sin servant”, “fear and trembling for judgement”, “sin rod”, “hell”, “wrath”, “guilt” and “sin” again and again – these are the terms that stand out from the text on which the cantata “I poor man, I sin servant” is based. Not a pleasant background for a piece of musical edification for the 22nd Sunday after Trinity.

We took the cantata text on a trip to Varanasi last early summer and read it in the shady park of Banaras Hindu University. To Sarnath outside Benares, the wildlife park where Siddhartha Gautama first preached the dharma after enlightenment, to the ghats along the Ganges and to a nightly Hindu fire ritual accompanied us, from which we sought, ultimately unsuccessfully, to make sense of the con ditio humana.

Over the years, apart from Mecca, we have visited all the holy places on earth – from the pyramids in Tikkal to the holy shrine of Ise in Japan. Varanasi, which like Jericho claims to be the oldest continuously inhabited settlement of mankind, has taught us how to deal with death. Here there is no suppression of the fate towards which we are all inevitably heading. The way the dead are delivered to the ghat around the clock, quickly cremated on wooden piles without much ceremony, and the cremation sites prepared by the workers with mechanical devices for the next corpse, is how it must have been in times of plague in Europe. Varanasi conceals nothing and leaves not the slightest doubt as to the finality of the fate of every inhabitant of the earth. And yet, it is precisely Varanasi that reconciles us with death and frees it from the clutches of hell, guilt and sins.

Tradition has it that in the family into which I married, the passing of the ashes takes place in Haridwar not far from Rishikesh on the upper reaches of the Ganges. Saying goodbye is part of our everyday experience and, no matter how much we try to repress it, it is something we all have to do, including saying goodbye to our dearest and most cherished ones. The transfer of the ashes into the river to the mantras of the priest and then the disappearance of the last flowers on the lively waters of the still youthfully unruly Ganges remain in our memories. Nothing remains – everything flows away!

Return to the world’s glory

Anyone who follows the truly dismal news that is shaping Europe’s image in the world public in these weeks and months cannot help but ask what has gone wrong with the old continent. Obviously, Asia, and in particular the two advanced civilisations of India and China, are in the process of regaining their global standing, which they possessed until well into the 18th century, with great dynamism. Europeans are thus forced, nolens volens, to discard their cherished Eurocentrism, not only in economics but also in culture, not only in trade and change, but also in thinking.

The times when world history was essentially European history are definitely over. Even the beloved Jacob Burckhardt can no longer claim the validity he possessed half an age ago. It is not only high time, but also a great gain, if we Europeans overcome the thresholds of Eurocentrism sooner rather than later and engage with Asian thinking, with Asian cultures and religions. I don’t mean this in a cultic sense – we don’t have to go on a yoga trip or a Taichi regime. Rather, it helps to pause for a few moments to consider why we actually believe what we believe and why and with what reasons other cultures have different beliefs.

The cantata text makes one thing clear – ultimately, faith is about nothing other than coming to terms with the inevitable, that our lives and the lives of our loved ones are finite. It takes a lot of courage to come to terms with the fact that when the last hour strikes, everything earthly, however much we may have possessed of it and however attached to it, is lost. Even the most abstruse dogmatics and the most elaborate scholasticism do not change this. Jesus and Mohammed probably knew this too, but they left their followers with a palatable palliative in the form of the afterlife and paradise.

The great sage – not the founder of a religion! – Confucius is more honest. His tomb, a mound of grass with a simple stele in the Kong family cemetery in Qifu in the eastern Chinese province of Shandong, has a clear message: “Everything ends here!” This message is of far-reaching civilisational significance and has shaped China for more than two and a half millennia. The pragmatism of the Chinese, which we have seen during the last three decades in the implementation of far-reaching economic and social reforms, is a consequence of the fact that for Confucianism there is no metaphysics, no speculation about the after. In this life you have to make it, there is no later correction!

The simplicity of the thought-saying

“Sinner”, “guilt” and “hell” – we know no such words from Hinduism, Buddhism, Taoism or Shintoism. In every religion, the priestly caste wants to elevate itself above the common people, this is part of the job description, so to speak. in Hinduism, priests mumble incomprehensible words in Sanskrit, the faithful mumble along and understand even less of the whole hullabaloo. in Buddhism, there are elaborate death rites that can cost a whole fortune in Japan and bring the Buddhist orders a hefty cash flow. in Shintoism, you can always consult the list of vintages on New Year’s Day that have to reckon with difficulties in the new year.

The message is clear: Donate a smaller or larger ritual and you can avert the trouble.

“Pecunia non olet!” is certainly not the only thing the Catholic Church has adopted from the Roman Empire, but it is probably the most profitable, as the whole indulgence and devotional trade and the lucrative pilgrimage business demonstrate. Religious institutions cannot survive without Mammon either. After all, there is no church tax in Asian religions. One pays at the temple, at the shrine for the service one claims.

The expulsion of the changers from the temple is reminiscent of Indian caste thinking. Here, the merchants rank far below the Brahmins, even behind the warriors. And yet, it is the traders, the merchants, entrepreneurs, bankers, who make life on this earth more bearable, at least in a material sense – and let’s face it, that is no small thing! In contrast, the warrior destroys and plunders, and the Brahmin, the priest lives from the added value of the national economy.

So why this ambivalence towards wealth, towards material well-being, which has such a great influence in Christianity? Money, consumption, sensual pleasures so easily move into the neighbourhood of sin, transgression, decay, wickedness! The Asian religions suit us better, not to mention the wisdom teachings of Confucius, which received their modern mantra in the famous saying of the great Chinese reformer Deng Xiaoping, “to become rich is wonderful”. We know why Deng gave this motto to his compatriots: For four decades, Mao Zedong had preached that “to be poor is wonderful”, thus relegating his people to the Stone Age. In such a devastated country, people first had to be freed from the twisted ideological shackles.

Of course, we all know that wealth, prosperity and physical well-being alone do not bring happiness – the omen of illness, of death is always on the wall! And even the best-equipped bank account is ineffective against death. But let us be honest – without wealth, without prosperity, without physical well-being, life is a very miserable, a very dreary thing. Self-mortification, poverty as preparation for the inexorably approaching death? Why should we, since death takes away from us in time what we can enjoy with our senses on earth? So let us, as ordinary mortals, postpone austerity until after we enter eternity, and in the few years that remain, let us also devote ourselves to enjoyment.

Religion – a human creation

The Sermon of Varanasi, delivered by Buddha in the Sarnath Wildlife Park near Varanasi, is considered the authoritative word on the path that should lead to the Dharma, to the building blocks of reality or, in the words of the German Indologist and religious scholar Helmuth von Glasenapp, to the “factors of existence”. The sermon is the core of Buddhist ethics and encompasses the most important teachings of Buddhism in the most concise space.

It is the case with sacred texts in all religions that they leave plenty of room for interpretation. Of course, this also means that they can be misused for all kinds of purposes. After all, religion does not take place beyond politics, society and the economy. It can serve to justify power as well as the persecution of heretics and people of other faiths. After all, as much as its protagonists want to elevate it to the realm of the divine, it is ultimately a human creation and thus prone to all the faults, but also all the strengths, that we humans have.

We know – especially after the tragic, bloody 20th century – that extremisms bring nothing but hardship and suffering. If anything threatens the survival of our species, it is the tendency towards fanaticism, which is also and above all nourished by religions and which not infrequently makes use of the apocalypse. When I think of all the things I am accused of and threatened with in this cantata text, I must indeed become fearful and anxious. Nothing can save me but to submit unreservedly to the dictates of the only beatifying Christianity.

All this is countered by the well-tempered tone of the Varanasi sermon. Moderation, the middle way should be the measure of all things. And this is precisely in the sights of the Varanasi sermon. Of course, Buddha recognised that suffering and pain are the result of deprivation and that, according to the classical logic of the enlightened man, suffering and pain can be reduced by letting go as much as possible in this life. Those who no longer have any attachments, either to themselves or to their environment, are on the path to nirvana, the state of complete needlessness and thus also freedom from suffering. in the metaphysical sense, which here also has a very strong nihilistic appeal, however, this complete self-removal is equated with eternity. No paradise, no hell beckons or threatens after death. Buddhism grew on Indian soil and displaced Hinduism in India itself for a few centuries before the latter returned powerfully almost a thousand years ago. Today, in the motherland of Buddhism, only an extremely small minority professes Buddhism. The only majority Buddhist country in South Asia is Sri Lanka.

In the Hindu understanding of karma, of fate, which shapes the life of the individual and from which he cannot escape, rebirth has an element of punishment or reward, which can be compared with the Christian ideas of hell, purgatory and heavenly paradise. Those who live in misery, according to Hindu teachings, probably attribute this miserable fate to misdeeds in their previous lives, for which they must pay in their new existence.

This understanding is alien to Buddhism. There is no actual individualised rebirth. The continuation of those who have not reached nirvana takes place in an anonymous form. Matter and soul continue in a manner detached from the person. Thus, of course, the element of punishment found in Hinduism is eliminated. The aim is to minimise the suffering that afflicts every human being, including Prince Siddhartha Gautama. According to Buddhist teachings, suffering is the result of clinging to things and people from whom one will inevitably be separated by death. Those who detach themselves from such attachments reduce their suffering and can ideally enter into sufferingless and thus attachmentless nirvana. We are not wrong if we see in this detachment a form of nihilism, which is ultimately also characteristic of the nature religion of Shintoism.

In passing, it should be noted that Buddhism has successfully applied its adaptability to local values and religious ideas, noted in the Indian context, to China as well. We are thinking of the adoption of ancestor veneration, which in the Middle Kingdom is part of Confucian ethics, but which ultimately points far back into primeval times, long before the time when Buddhism came to China from India in the first century AD.

Regret instead of condemnation

“Sin rod”, “fear and trembling” before judgement – all these are absent in Buddhism. There is no Last Judgement, and anyone who is addicted to the good life, the material, the senses, the attachment to things and people, is not committing a sin but, if it should be an existential need for him to reduce his suffering on earth, is simply committing a mistake. Buddhism does not condemn him for this mistake, but simply regrets it.

In this context, the emphasis on the middle way in the Varanasi sermon is particularly significant. The Buddha said: “Neither abstinence from fish and flesh (meaning the violation of the Buddhist precept not to kill living beings, author’s note) nor going naked (needlessness) nor shaving the head hair (chastisement of monks and nuns) (…) nor wearing rough clothes (mortification) (…) nor offering to Agni (god of fire) purifies a person who is not freed from self-deception (illusions about the nature of human existence). “

On the middle way, Buddha says: “To satisfy the needs of life is not evil. Keeping the body in a good state of health is a duty (…) otherwise we cannot keep our mind strong and clear (mens sana in corpore sano).” The middle way passes between “overindulgence” and self-mortification: “With his suffering, the starved believer only causes confusion and morbid thoughts. Mortification does not promote inner-worldly wisdom, and still less does it lead to victory over the senses.”

Again, the sermon of Varanasi is not a call to abstinence from life in this world, not an instruction on how to reach paradise through self-destruction. Quite the opposite. Again and again, Buddha emphasises the value of the middle way, of moderation, of rejecting extremes and absolutes. The “noble truth” for overcoming sorrow and pain is: “right views, right aspirations, right speech, right conduct, right attitude to life, right effort, right thought and right contemplation.” This is the eightfold path.

What is right is not determined by the compulsion of a dogma, a righteous doctrine, an ideology. The search for what is right is up to the individual. He can at best take precepts from the Buddha, but he can also take precepts from other ethics for his edification. However, he has to find the way himself and cannot or does not have to rely on consecrated priests, gurus or others. Nothing releases the person who has set out on the path of searching for what is right from this duty. Self-responsibility, not subordination to a karma, to a god, be he punishing or loving, is the maxim of the Buddha. Let us try to explain original sin, the sinfulness of man, from this point of view! The refusal of self-responsibility, the turning away from the right path, these are all not sins, but simply mistakes, omissions, which I commit to my own detriment, in that I am not thereby able to reduce my suffering, which consists in the separation from all that is dear to me. In the light of the sermon of Varanasi, which praises the entrance into Nirvana, into the complete extinction of everything earthly and the resulting liberation in death, let us consider the dark monstrosity of the word “death as the wages of sin” (Romans 6:23), which resonates in the cantata text.

“Fear and trembling for judgement”, “hell”, “wrath”, “guilt” and “sin” – in Buddhism, all these concentrated threats are simply opposed by the instructions for perhaps possible self-responsible overcoming of the earthly suffering that arises from the loss, the separation – nothing more, but also nothing less!

This text has been translated with DeepL (www.deepl.com).