Erfreut euch, ihr Herzen

BWV 066 // For the Second Day of Easter

(Rejoice, all ye spirits) for alto, tenor and bass, vocal ensemble, trumpet, oboe I+II, bassoon, strings and continuo

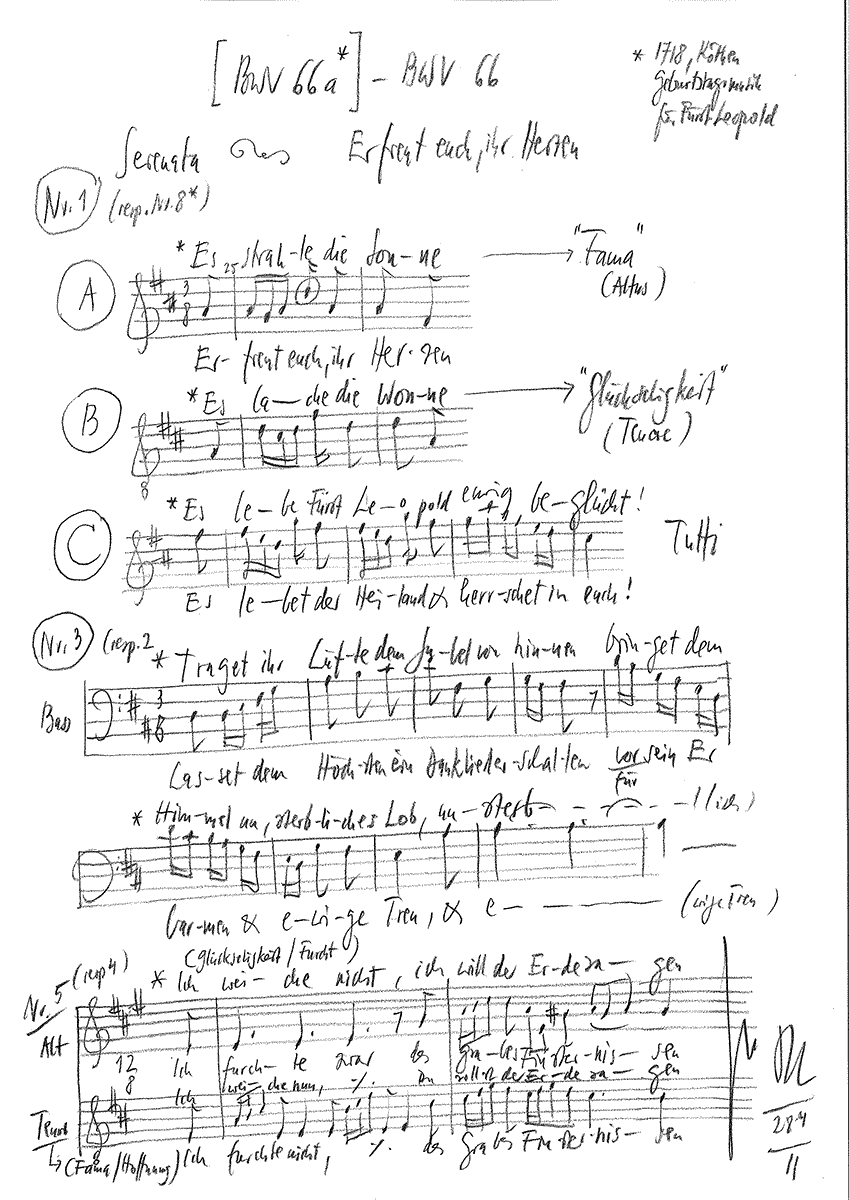

Written in Leipzig, Bach’s Easter cantata BWV 66 (preserved in its 1731 version) is a sacred parody based on a Cöthen serenade of 1718. Bach opens the work by taking the spectacular closing movement of the original – “Let sun shine forever, let pleasure bring laughter, let prosper Prince Leopold ever in Bliss” – and reworking it as an introductory chorus to the text of “Rejoice, all ye spirits, depart all ye sorrows, alive is our Saviour and ruling in you”.

Would you like to enjoy our videos ad-free? Subscribe to YouTube Premium now...

Workshop

Reflective lecture

Choir

Soprano

Susanne Frei, Guro Hjemli, Jennifer Rudin, Noëmi Sohn, Alexa Vogel

Alto

Jan Börner, Antonia Frey, Olivia Heiniger, Katharina Jud, Lea Scherer

Tenor

Marcel Fässler, Manuel Gerber, Raphael Höhn, Nicolas Savoy

Bass

Fabrice Hayoz, Manuel Walser, William Wood

Orchestra

Conductor

Rudolf Lutz

Violin

Renate Steinmann, Martin Korrodi, Christine Baumann, Sabine Hochstrasser, Yuko Ishikawa, Ildiko Sajgo

Viola

Susanna Hefti, Martina Bischof

Violoncello

Maya Amrein, Martin Zeller

Violone

Iris Finkbeiner

Oboe

Katharina Arfken, Dominik Melicharek

Bassoon

Dorothy Mosher

Tromba da tirarsi

Patrick Henrichs

Organ

Norbert Zeilberger

Musical director & conductor

Rudolf Lutz

Workshop

Participants

Karl Graf, Rudolf Lutz

Reflective lecture

Speaker

Gottlieb F. Höpli

Recording & editing

Recording date

04/29/2011

Recording location

Trogen

Sound engineer

Stefan Ritzenthaler

Director

Meinrad Keel

Production manager

Johannes Widmer

Production

GALLUS MEDIA AG, Switzerland

Producer

J.S. Bach Foundation of St. Gallen, Switzerland

Librettist

Text

Poet unknown

First performance

Second Day of Easter,

10 April 1724

In-depth analysis

Written in Leipzig, Bach’s Easter cantata BWV 66 (preserved in its 1731 version) is a sacred parody based on a Cöthen serenade of 1718. Bach opens the work by taking the spectacular closing movement of the original – “Let sun shine forever, let pleasure bring laughter, let prosper Prince Leopold ever in Bliss” – and reworking it as an introductory chorus to the text of “Rejoice, all ye spirits, depart all ye sorrows, alive is our Saviour and ruling in you”. Characterised by its orchestral writing, this light and catchy movement is equally effective as a sacred work, with the calls of the choir in the twopart section no longer acclaiming the provincial rulers of Anhalt, but the victorious prince of heaven. The ad libitum trumpet part, largely moving in parallel with the violin or oboe, is evidently a Leipzig addition that Bach used to fortify the Easter mood, while the devout and humble middle section of the serenade (“Ah heaven, we pray now”) is recast as the “fainthearted anguish” of the disciples in the face of the overwhelming Easter events.

The bass recitative imparts its weighty message of Jesus’ resurrection and eternal triumph over death in a dense string setting that waits until the end of the movement before resolving into a joyous Easter fanfare. In contrast, the rich string and woodwind scoring of the bass aria applies the pomp of courtly festive music to a glorious song of thanksgiving to God, in which the soloist appears to mimic a virtuoso bassoonist in a catchy, yet distinctive orchestral dance.

A more sceptical tone soon returns, however, in the recitative. After the assured quality of the opening lines (“In Jesus’ life to live with joy”), an arioso dialogue somewhat abruptly ensues between the allegorical figures of “Fear” (alto) and “Hope” (tenor), whose textually contrasting lines (“Mine/No eye hath seen the Saviour raised from sleep”) and conflicting emotions of confidence and doubt eventually segue into an appeal for comfort and strength.

The penultimate movement, a duet with obbligato violin, retains the dialogue structure of the Cöthen original, but allows one voice to express belief in the resurrection while the other bemoans the “stolen” redemption; not until the middle section do the voices unite and proclaim together “Now is my heart made full of hope”. This mood is carried over to the closing chorale, composed especially for the Leipzig version, whose three cries of “Alleluja!” invite the congregation to join in an archaic yet timelessly powerful Easter song. Punctuated by organ interludes so typical of the time, this movement, like many of Bach’s Easter chorales, is a potent reminder that the hard-won resurrection is a festival of grave import.

Libretto

1. Chor

Erfreut euch, ihr Herzen,

entweichet, ihr Schmerzen,

es lebet der Heiland und herrschet in euch.

Ihr könnet verjagen

das Trauren, das Fürchten,

das ängstliche Zagen,

der Heiland erquicket

sein geistliches Reich.

2. Rezitativ (Bass)

Es bricht das Grab und damit unsre Not,

der Mund verkündigt Gottes Taten;

der Heiland lebt, so ist in Not und Tod

den Gläubigen vollkommen wohl geraten.

3. Arie (Bass)

Lasset dem Höchsten ein Danklied erschallen

vor sein Erbarmen und ewige Treu.

Jesus erscheinet, uns Friede zu geben,

Jesus berufet uns, mit ihm zu leben,

täglich wird seine Barmherzigkeit neu!

4. Rezitativ à 2 und Arioso (Duett Furcht: Altus, Hoffnung: Tenor)

Hoffnung

Bei Jesu Leben freudig sein

ist unsrer Brust ein heller Sonnenschein.

Mit Trost erfüllt auf seinen Heiland schauen

und in sich selbst ein Himmelreich erbauen,

ist wahrer Christen Eigentum.

Doch weil ich hier ein himmlisch Labsal habe,

so sucht mein Geist hier seine Lust und Ruh,

mein Heiland ruft mir kräftig zu:

«Mein Grab und Sterben bringt euch Leben,

mein Auferstehn ist euer Trost.»

Mein Mund will zwar ein Opfer geben,

mein Heiland, doch wie klein,

wie wenig, wie so gar geringe,

wird es vor dir, o grosser Sieger, sein,

wenn ich vor dich ein Sieg-

und Danklied bringe.

Hoffnung

Mein Auge sieht den Heiland auferweckt,

Furcht

Kein Auge sieht den Heiland auferweckt,

Hoffnung

es hält ihn nicht der Tod in Banden.

Furcht

es hält ihn noch der Tod in Banden.

Hoffnung

Wie, darf noch Furcht in einer Brust entstehn?

Furcht

Lässt wohl das Grab die Toten aus?

Hoffnung

Wenn Gott in einem Grabe lieget,

so halten Grab und Tod ihn nicht.

Furcht

Ach Gott! der du den Tod besieget,

dir weicht des Grabes Stein, das Siegel bricht,

ich glaube, aber hilf mir Schwachen,

du kannst mich stärker machen;

besiege mich und meinen Zweifelmut,

der Gott, der Wunder tut,

hat meinen Geist durch Trostes Kraft gestärket,

dass er den auferstandnen Jesum merket.

5. Arie (Duett Furcht: Altus, Hoffnung: Tenor)

Altus

Ich furchte zwar des Grabes Finsternissen

und klagete mein Heil sei nun entrissen.

Tenor

Ich furchte nicht des Grabes Finsternissen

und hoffete mein Heil sei nicht entrissen.

Beide

Nun ist mein Herze voller Trost,

und wenn sich auch ein Feind erbost,

will ich in Gott zu siegen wissen.

6. Choral

Alleluja! Alleluja! Alleluja!

Des solln wir alle froh sein,

Christus will unser Trost sein.

Kyrie eleis.

Gottlieb F. Höpli

“From individuality to loneliness”.

The cantata “Erfreut Euch, ihr Herzen” (Rejoice, all you hearts) speaks to the self-confidence of the Christian and develops the vision of modern individuality. But the loneliness of the individual in our time may also have its origins here.

I confess: it took a while for the voices that resound in this cantata to speak to me. I don’t mean the three wonderful solo parts, nor the beautiful bass aria, nor the duets between tenor and alto, nor the virtuoso solo violin playing around them, nor the radiant wind instruments – no, I mean the voices that speak to us from the text of the cantata.

For the music of the cantata goes directly to the heart of the lover and also to the “approaching organist” – that’s how Bach describes the studiosus on the organ in the Orgelbüchlein – and to us today, in large parts, quite in contrast to the cantata text. Nothing other than Bach’s music is the reason for the monthly performances in Trogen in Appenzell over the next 20 years.

Talking about this music would be much easier for me according to the motto of my teacher Emil Staiger, the master of literary-historical interpretation. Because the mediating work of the reflective interpreter consists of “grasping what grips us” (no one has described the hermeneutic circle of interpretation more succinctly!). But those who reflect on music are known to run the risk of falling into the tone of Wackenroder and Tieck’s early Romantic “Herzensergiessungen eines kunstliebenden Klosterbruders” (1796).

So we turn to the cantata text from an anonymous pen: a text that must be typical of this genre of sacred vocal music, significant for Bach himself, for the churchgoers in St Thomas’ Church in Leipzig on that second Easter feast day in 1724 and consequently also for us. Some of the numerous voices in this cantata text, which have already been mentioned, come from far away. They speak to each other, they speak to the faithful – and they also speak to us. It is a whole network of voices that the listener is confronted with.

The first voice, the farthest away, calls out:

“Let the sun shine,

let joy shine,

Long live Prince Leopold, eternally happy.

Oh heaven, we implore,

to see the happy time sixty times again,

“Give us, most high, what refreshes our regent.”

The reader will immediately notice that these verses do not come from the text of the cantata “Erfreut euch, ihr Herzen”. But anyone who reads the text of the opening chorus of our cantata carefully (“Erfreut euch, ihr Herzen, / entweichet, ihr Schmerzen”) will immediately realise that the music fits both texts. Or should we rather say: both texts fit the music?

The text quoted here forms the conclusion of a “Serenata” that Bach composed and performed in 1718 for the 24th birthday of his Köthen employer, the music-loving Prince Leopold zu Anhalt-Köthen. There is much to be said about this form of using earlier models, the parody, as it is also known from other cantatas, both practical and fundamental. For example, that Bach wrote the St John Passion for Good Friday 1724 and, pressed for time, reworked already existing cantatas for the two following Easter days.

In this context, however, it should not go unmentioned that the joy of a birthday and the joy of the resurrection are characterised by very similar affects. In fact, affects, the art of depicting precisely defined and typified states of mind and arousing them in the audience, play a very central role in Baroque music. What’s more, Johann Sebastian Bach always comes up with more for a birthday than many composers do for an ecclesiastical festival …

The voices in the cantata “Erfreut euch, ihr Herzen” (Rejoice, Ye Hearts) are closer to our ears than the text of the court music from Köthen, holding a dialogue, a kind of argument, between hope (tenor) and fear (alto). The two affects give expression to the human ambivalence before the Easter mystery, and they are not unknown to today’s Christians either. Not in the baroque choice of words, but in the ambivalent attitude: “(…), / I believe, but help me weak, / you can make me stronger; / (…)”. For doubt – our secularised present seems to have completely forgotten this – is not the characteristic of the unbeliever, the non-interested, nor of the know-it-all, but the characteristic of the believing, searching person struggling for his faith!

Looking at the cantata as a whole, one is struck by the radiance, the ear-catching jubilation about the resurrection that resounds there. Particularly moving in the case of that millennial voice that resounds at the very end and immediately falls silent again: the third stanza from the oldest liturgical Easter hymn in the German language, “Christ ist erstanden” (Christ is risen), which goes back to an even older Latin original. The ancient Easter hymn is recalled in all three stanzas (our inner ear may hear the ancient Doric key with its whole-tone steps):

“Christ is risen from the torment all;

We should all be glad,

Christ will be our comfort.

Kyrieleis.

If he had not risen,

the world would have passed away;

since he is risen,

we praise the Father Jesus Christ.

Kyrieleis.

Hallelujah,

Hallelujah,

Hallelujah!

Let us all be glad,

Christ will be our comfort.

Kyrieleis.”

With this ancient Easter sequence, Bach, it seems to us, put a kind of additional stamp of faith under the cantata, similar to the three letters he put under many of his works: SDG – Soli Deo Gloria.

At this point, at the latest, we today are inevitably confronted with the faith content of the Easter event: the resurrection of Christ is not for lukewarm Christians and rationalists, it is “hard stuff”. Can we contemporaries at Christmas still find the birth of a baby of poor people in the far East somehow touching, the resurrection of Christ demands a completely different positional reference: Do you believe in the redemption through the sacrifice of the Son of God in the Passion, in his resurrection and his ascension? It is no coincidence that the Orthodox Church attaches a completely different, a central significance to the Easter event in the church year. The Easter Vigil in the Orthodox liturgy with its cries of resurrection and its never-ending jubilation – which I have certainly been able to celebrate twenty times so far – is an incomparable, overwhelming spiritual experience!

But we have still not come close to the core message of the cantata text. It still sounds to us as if from far away. And yet, at least at one central point, our present connects with the text much more than can be perceived at first glance.

Let us ask: In the text of this cantata, what constitutes a “true Christian”? In the tenor recitative it says:

“Looking with consolation on his Saviour

and build in himself a kingdom of heaven,

is the property of true Christians.”

“To build in oneself a kingdom of heaven”: now that is truly a Reformation statement, almost a pietistic one! We do not find it anywhere else, neither with the Catholics nor with the Orthodox, nor in any other world religion: the individual is, I myself am, quite alone in the position to “build” a “kingdom of heaven” in myself! Without spiritual or worldly permission, without priestly mediation, without princely decree of grace! This detachment of the individual from the manifold horizontal and vertical ties of the medieval world will have tremendous consequences. Here begins a process of emancipation, loosening and detachment, finally the cutting of ties, which then did not even stop at man’s bond with God – and nothing else meant “religio”. A process that will go on and on in the course of time. It leads directly to the Enlightenment, defined by Kant in 1784 as “man’s exit from his self-inflicted immaturity”, and to the imperative “Have the courage to use your own intellect”.

This no longer requires a personalised God; since Kant, all that is needed is the consciousness of “the starry sky above me and the moral law within me” – because the enlightened person can assume that this consciousness is also present in his neighbour. As is well known, the enlightened optimism of living in the best of all worlds suffered a lasting blow after the Lisbon earthquake of 1755, as we know from Voltaire’s “Candide”.

The developmental thread of individualisation could be continued right up to the present day. Of course, that would go beyond the scope of this reflection. Only this much: individualisation also means isolation, even loneliness. The loneliness of modern man is no longer just a dominant theme of today’s art and literature, but now also preoccupies sociologists and even urban planners. The latter have to gear urban living space, urban space, more and more to the dominant species of singles.

Returning to the beginning of the cantata, our now sharpened hearing quickly allows us to see what separates us from the spirit of the cantata today:

The verses “Erfreut euch, ihr Herzen, / entweichet, ihr Schmerzen, (…)” would certainly be conceivable in today’s secularised world and even a hundred years ago – but no longer as a jubilation about the Saviour’s victory over hardship and death, about the comfort that he thus provides us, but rather, for example, in an advertising slogan about the effect of a painkiller from the 1920s. The pharmaceutical industry has long since overtaken the healing effect of faith! So the following lines, which speak of the Saviour and his spiritual kingdom, would have to be re-phrased, for example to the name of a prominent drug, perhaps even a psychopharmaceutical! I will be forgiven if I refrain from this attempt.

It is true that modern man has not completely severed his ties to the afterlife. It may even be said that the longing for such a connection has rather grown again. But the starting point is now the individual life plan, which wants to determine for itself in which forms and rites this connection should take place – “bottom up” instead of “top down”, as it is called today. A visible example of this are the often extremely embarrassing, self-made rites that people come up with when they don’t want to completely do without the services offered by the churches when they tie the knot for life. Instead of Johann Sebastian Bach and the organ, well-intentioned words of friendship, guitar and drums and a musical quality that is often quite subterranean are then used. i think – this is my personal opinion – that our national churches and their staff today allow themselves to be offered too much in this respect!

Let’s talk one last time about the kingdom of heaven, which man can, indeed should, build in himself. Since Immanuel Kant at the latest, however, this has also meant that man himself is responsible if he does not manage to create paradisiacal conditions within himself. And this has not become any easier since navel-gazing and looking into the abysses of the human soul have made such enormous progress in the last century …

A word about the abysses of the soul: The Greek Pindar’s pedagogical call to man, “Become who you are”, has already become Nietzsche’s ominous “How to become what you are” – it is the subtitle of the torn late work “Ecce homo”, which the philosopher and despiser of Christianity wrote shortly before his collapse: “Ecce homo” – the exclamation of Pontius Pilate at the sight of Jesus Christ, shortly before he allowed the Passion of Christ, which he could not stop, to run its course.

But the passion was followed by the resurrection. No one will want to claim that in a present full of fears, passions and obsessions, people do not long for some kind of redemption. But of the two dialogue partners in the cantata “Rejoice, Ye Hearts”, fear and hope, fear clearly reigns supreme today. The media are also largely responsible for this – to the extent that, as a rule, only bad news is good news for the newspaper man. Therefore, the media are the worst possible bearers of good news and certainly not simple representations of reality. “Rejoice, you hearts, / escape, you pains” would only be headline-grabbing for them if it were a state of emergency for one day, for example on the day of a royal wedding like this 29 April 2011, the “Royal Wedding”. The media, not only today, but ever since they have existed, have been at the service of the baroque affect of fear, depicting it in all possible states and wanting to arouse it in their audience as dramatically as possible. In this way, they resemble the Fama from the Köthen Birthday Serenata to a tee.

But this may now be the legitimate occasion to abandon this un-Easterly train of thought and return from the serenata to the cantata! Even today, Johann Sebastian Bach’s wonderful music can give us hope, even a piece of the “kingdom of heaven within ourselves”.

This text has been translated with DeepL (www.deepl.com).