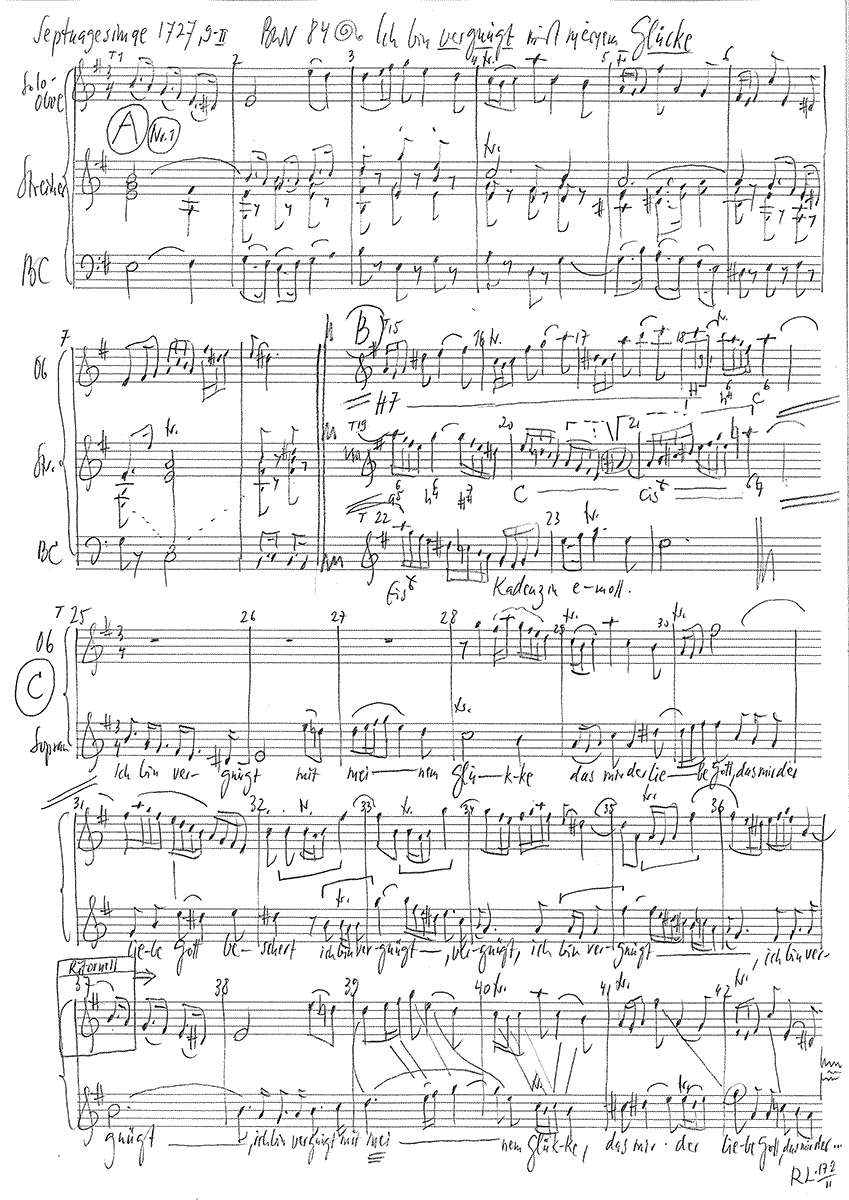

Ich bin vergnügt mit meinem Glücke

BWV 084 // For Septuagesimae

(I am content with my good fortune) for soprano, vocal ensemble, oboe, bassoon, strings and continuo

The cantata “Ich bin vergnügt mit meinem Glücke” (I am content with my good fortune), probably composed in 1727, is one of Bach’s few sacred solo works. Theologically, it is based on the parable of the workers in the vineyard (Matthew 20), which Bach and his librettist approached less as a precedence in labour law, than as a point of departure for the moral observation that the path to true contentment can only be found in submission to God’s will. In a spirit of almost cheerful humility and studied serenity, Bach succeeds in composing a veritable “Franciscan cantata”, whose modest length and sparse scoring is, in itself, a fitting formal interpretation of the text’s message.

Would you like to enjoy our videos ad-free? Subscribe to YouTube Premium now...

Workshop

Reflective lecture

Soloists

Soprano

Gerlinde Sämann

Choir

Alto

Antonia Frey

Tenor

Walter Siegel

Bass

Fabrice Hayoz

Orchestra

Conductor

Rudolf Lutz

Violin

Renate Steinmann, Martin Korrodi

Viola

Susanna Hefti

Violoncello

Martin Zeller

Violone

Iris Finkbeiner

Oboe

Katharina Arfken

Bassoon

Dorothy Mosher

Organ

Rudolf Lutz

Musical director & conductor

Rudolf Lutz

Workshop

Participants

Karl Graf, Rudolf Lutz

Reflective lecture

Speaker

Eleonore Frey Staiger

Recording & editing

Recording date

02/18/2011

Recording location

Trogen

Sound engineer

Stefan Ritzenthaler

Director

Meinrad Keel

Production manager

Johannes Widmer

Production

GALLUS MEDIA AG, Switzerland

Producer

J.S. Bach Foundation of St. Gallen, Switzerland

Librettist

Text No. 1–4

Poet unknown

Text No. 5

Ämilie Julyane von Schwarzburg–Rudolstadt, 1686

First performance

Septuagesima Sunday,

9 February 1727

In-depth analysis

With its head motive of descending dotted notes, the introductory aria embodies a vision of forbearance that – through the effortless, flowing lines of the soprano, oboe and obbligato first violin – is also presented as a precondition for true freedom. Here, the movement’s apparent simplicity and all-pervasive lightness seems to express a richness of inner life that finds lasting contentment in the appreciation of the smallest gifts. One can well imagine that this virtuous picture of gracious simplicity and dignified penury may perhaps have been personified by a female figure in Bach’s life.

The following recitative traces this attitude to life back to the Lutheran tenet of justification by faith as well as to the basic conditions for human existence – food, clothing and not least respect for God and one’s neighbour. Indeed, the person to whom all this has been given is unable to earn any right to salvation, but must eat with patience the “humblest of bread” as described in the ensuing aria. Set once again as a light-hearted dance movement in 3/8 time, the charming quartet of oboe, violin, voice and continuo invokes the infectious joy that comes from loving one’s neighbour – a most effective musical sermon.

By scoring the accompaniment for both organ and strings, Bach lends particular weight to the second recitative, in which the parable of the vineyard is extended to the course of earthly life. Here, the way in which Bach engraves the liberating word of “heaven” on the coin of life is of a moving intensity that transcends all earthly frugality.

Through its simple setting, the closing chorale enhances the central message of the temporary earthly duties entrusted to us by God as well as the hope for an undeserved, but patiently awaited “good end”. Here, Bach’s decision to set a verse of the death song “Wer weiss, wie nahe mir mein Ende” to the hymn of forbearance “Wer nur den lieben Gott lässt walten” effectively melds the two levels of the parable. The “3 Ripieni” (additional singers) called for in the original score to support the soprano solo in this final movement have indeed been put to a most satisfying use.

Libretto

1. Arie (Sopran)

Ich bin vergnügt mit meinem Glücke,

das mir der liebe Gott beschert.

Soll ich nicht reiche Fülle haben,

so dank ich ihm vor kleine Gaben

und bin auch nicht derselben wert.

2. Rezitativ (Sopran)

Gott ist mir ja nichts schuldig,

und wenn er mir was gibt,

so zeigt er mir, dass er mich liebt,

ich kann mir nichts bei ihm verdienen;

denn was ich tu, ist meine Pflicht.

Ja! wenn mein Tun gleich noch so gut geschienen,

so hab ich doch nichts Rechtes ausgericht’;

doch ist der Mensch so ungeduldig,

dass er sich oft betrübt,

wenn ihm der liebe Gott nicht überflüssig gibt.

Hat er uns nicht so lange Zeit

umsonst ernähret und gekleid’

und will uns einsten seliglich

in seine Herrlichkeit erhöhn?

Es ist genug vor mich,

dass ich nicht hungrig darf zu Bette gehn.

3. Arie (Sopran)

Ich esse mit Freuden mein weniges Brot

und gönne dem Nächsten von Herzen das Seine.

Ein ruhig Gewissen, ein fröhlicher Geist,

ein dankbares Herze, das lobet und preist,

vermehret den Segen, verzuckert die Not.

4. Rezitativ (Sopran)

Im Schweisse meines Angesichts

will ich indes mein Brot geniessen,

und wenn mein’ Lebenslauf,

mein Lebensabend wird beschliessen,

en, so teilt mir Gott den Groschen aus,

da steht der Himmel drauf.

O! wenn ich diese Gabe

zu meinem Gnadenlohne habe,

so brauch ich weiter nichts.

5. Choral

Ich leb indes in dir vergnüget

und sterb ohn alle Kümmernis,

mir g’nüget, wie es mein Gott füget,

ich glaub und bin es ganz gewiss:

Durch deine Gnad und Christi Blut

machst du’s mit meinem Ende gut.

Eleonore Frey

“The Secret of Small Gifts”

I

“Ich bin vergnügt mit meinem Glücke”: in the echo of the music of the cantata BWV 84, I remember the “happiness” that is sung about in the pleasure of God’s gift, not as the jubilation that seems to be spoken of in the first words of our cantata. Pleasure is silent, happiness is not the great lot. The subdued, rejoicing song gives space to what could easily be disregarded in rousing hymns of praise: the “small gifts” that are supposed to compensate the modest aspirant for the “rich abundance” that eludes him. That these are by no means to be disregarded became perhaps clearer to me than ever before when I marvelled at the flowers in Spitsbergen the summer before last, which wrung their astonishing bloom out of the conceivably meagre conditions there. Not that they were very different from the ones here. There were carnations and buttercups, woolly grass and saxifrage and other things that are familiar to us from the mountains. But even if they were not very different in kind from our native plants, they were different in their sharp tininess, in the intensity of their colours, in their exposure in a place where no trees grew and where spring, summer and autumn could be combined into a single season: the one in which it was bright, in which an abundance of light contrasted with the lack of the long, dark times. How they smelled, and whether they smelled at all, I do not know. Since one was not allowed to pick the flowers because of their preciousness, I would have had to lie down to get my nose close to them – which was not advisable in view of the nature of the soil. Plants that one treads on carelessly in other latitudes were carefully avoided here: The flora, which grew exclusively in small and very small gifts, had become a miracle here, behind which the splendour of the orchids, roses and lilies growing wild elsewhere fell far short.

If one reads the beginning of the cantata with regard to its contemporary use of language, “pleasure” as well as “happiness” appear in a light that is unfamiliar to us. Both the one and the other word are used here in a meaning that is only familiar to us from older texts. Not as clearly good, but fluctuating between good and bad fortune: “happiness”. Not in the sense of a cheerful joy, but as a simple contentment: “People are never happy with their status”, laments Friedrich von Logau in one of his aphorisms. And in the poem “Gebet” (Prayer) by Mörike it says: “Herr, schicke was du willt / ein Liebes oder Leides / ich bin vergnügt, dass beide / aus deinen Händen quillt – ein Liebes oder Leides” (Lord, send what you will / a love or sorrow / I am pleased that both / spring from your hands – a love or sorrow), as Schiller’s “doubting happiness” wants.

When I had just begun to think about the text of this Bach cantata, I discovered to my surprise that the third canto of Dante’s “Paradise” speaks of a comparably frugal pleasure in God-given happiness. When Dante asks Piccarda, who has been transferred to the lunar heaven, if she would not rather ascend to a higher heaven, she answers him, “as cheerfully (…) as if she glowed in the highest love”:

“My brother, our will is satisfied

By the power of love, it only makes us desire

That which we have; other vapours vanish.

If we longed for another place,

Then our desires would not be in harmony

With the will that sends us here.”

In paradise there is no difference between wanting and having, the reader is told later. Or, one may perhaps say, where there is no difference between wanting and having, there is paradise. And if not paradise, then at least the desireless inner peace in which one’s eyes open to the “small gifts” that God bestows on those who cheerfully accept what He sends them. It should be added that this tranquillity itself is not at all a “small gift” and should be highly valued.

Outside of the religious context, in which this paradisiacal contentment with a fortune that always turns, opens up as a possibility, in the unequal, not to say unjust distribution of earthly goods of happiness, the desire for more will always have to come into play, and not without good reason. Whoever is not allowed to trust that a God, as it says in the cantata text, “feeds him in vain”, will not be able to eat his “little bread” with joy so easily, and probably also not necessarily be able to “grant his neighbour his own” from the heart. in harmony with God’s will can only be those who feel themselves taken care of in the hope of his grace.

A “small gift”? in the song, the gift is “small” in contrast to the “rich abundance” which it has to replace those who are “pleased” with little. “Small gifts” can also be those moments of happiness in which one – for once freed from the constraints of habit – sees with different eyes than what one usually sees. Where a ray of sunlight falls into a stream flowing rapidly downhill, I – attentive to this sudden brilliance – no longer see the flowing water, but – like a flash – the light refracted in it. Or, in the light of an abruptly appearing foreboding, a person’s face suddenly no longer appears to me as that of a weary, burdened person, but “as God meant it”, as I once heard someone say to my delight: a person from whom the affliction that otherwise characterises his expression and determines his behaviour has suddenly fallen away. You cannot want such events, but only accept them – as a small gift, as a small eternity in the midst of our everyday life, which unfortunately so often rushes from one thing to another. And it can occur to one in the memory of such moments that in them one has not only stepped out of the – in the precise sense – ruthless course of time, but also out of the self-evidence that presents this course of events to us as the only possible one.

II

I would now like to try to recall the text of the first aria in its setting:

“I am merry with my happiness,

which the good Lord hath bestowed upon me.

If I should not have rich abundance

I thank him for small gifts

Nor am I worthy of them.”

What sounds like a silent prayer in the spoken word blossoms in the setting into a music of speech in which the words are effective not only in their meaning but also as sound carriers. In this double purpose, the melody not only moves steadily towards its goal, pondering one word after another, but it also remains with itself in a certain sense when the same vowel is intoned one after another in the course of the melody and is thereby brought to the fore for its own sake, as a sound. Be it an “e”, an “i” or the “ü” that opens brightly upwards in “pleasure” as well as in “happiness” and “abundance”: in each of the more or less bright sounds that carry the melody wordlessly onwards, one can experience in a kind of acoustic enlightenment one of the “small gifts” for which the singer thanks her God in the awareness of her own insufficiency. A succession of “small gifts”, however, which in the free unfolding of the sounds and in the transparency of the chords accompanying them expands into a “fullness” that is, if not “rich”, then at least highly differentiated in itself, and which in its powerfully delicate radiance seems to open up an unlimited space.

The first aria expresses something in words that grows in song beyond what is said. As if “pleasure”, “happiness” would like to come closer to our modern usage of language after all. The music, however, as I said, does not soar to the “rich fullness” of jubilation that overwhelms us, for example, in Bach’s “Magnificat”, but rather it takes itself back again and again in its upswing, in order to then move at a measured pace to the next and once again the next note. In a series of “moments” radiating out of themselves, the notes combine to form a melody which, conscious of each individual step, thoughtfully seeks its way; as if – always questioned anew – the direction could only arise one after the other from the reflection on the note that has just faded away. If there is a will guiding this movement, it does not seem to draw its strength from an intention given in advance, but from one moment to the next from the tension in which the notes simultaneously remain with themselves and, imperceptibly transforming themselves, pass into the next and yet another next. In such attentiveness we do not, as is said (usually without any ulterior motive), put our way back like something that has taken care of itself as a means to an end, but we explore it, sound it out in every detail, as if we were on the way for its own sake. Not in the mode of “as if”, but in reality: carried by a confidence that makes us experience from moment to moment in the familiar the unfamiliar, in the finite the infinite.

Such attention can also be given another name. In Paul Celan’s Büchner Prize speech “The Meridian” there is the sentence: “Attention” – here, after Walter Benjamin’s Kafka essay, a word by Malebranche should be quoted – “attention is the natural prayer of the soul.” One reference after another leads back to the source from which Celan took the concept of the “natural prayer of the soul” and thus of a gift of God that cannot be called without timidity. Nicolas Malebranche, whose main work is entitled “De la Recherche de la Vérité”, could probably be a guarantee, first to Benjamin and then also to Celan, of the honesty of these so often misused words “soul” and “prayer”. in them, Celan found a way of describing the “ways of poetry” in such a way that their opening to “a completely Other” also becomes perceptible: To the one to whom the prayer is directed and who, with his creation, gives the poet the occasion for a work that – in attention – tries to say this creation anew. Word after word. Flower by flower. “Orchis and orchis one by one”, as it says in the poem “Todtnauberg”: in attention in such a way that the individual plant stands out from the “rich abundance” of vegetation and becomes recognisable as the miracle it is in its finely chiselled vulnerability.

Attention” as “the natural prayer of the soul”, “attention” as the prayer that discovers the “small gifts” and makes them blossom: in the music of our Bach cantata, which carefully describes its path, it gives itself as a gift, if one only engages completely with the sequence of sounds. If I try to follow the music with a keen ear and concentration, remembering in every step what has just been and anticipating what is about to be, I am not deprived of the movement in which the song presses forward, even if it remains suspended from moment to moment. In listening, we all come from a beginning and move towards an end. This is indispensable, just as in life we go from birth to death. In attentive listening, however, the possibility of a new beginning also reveals itself in each of the moments that come into effect in it as a kind of miracle. in it, the song not only moves forward, but it also finds itself again and again in the place from which the melody always takes its upswing anew. Thus, in the course of time, two movements are superimposed, one of which follows the course of things, while the other always seems to return anew to its origin. in passing, i also keep getting to the bottom of what i perceive in attention from one step to the next. “Orchis and orchis” or the precious blossoms in Spitsbergen: as if newly created, the plants grow towards me out of the soil that releases and nourishes them. Flower after flower. Or, from the air, word after word. Sound for sound.

This text has been translated with DeepL (www.deepl.com).