Herr Christ, der einge Gottessohn

BWV 096 // For the Eighteenth Sunday after Trinity

(Lord Christ, the only Son of God) for soprano, alto, tenor and bass, vocal ensemble, trombone, flauto piccolo, transverse flute, oboe I+II, bassoon, strings and continuo

Cantata 96 on Elisabeth Cruciger’s hymn “Herr Christ, der einge Gottessohn” (Lord Christ, the only son of God) opens with an introductory chorus in a style reminiscent of Christmas music; the charming pastoral scene is set in a lively 9/8 metre that is propelled forward by the light, yet accented gestures of the string, oboe and continuo lines. Although Bach used this earnest hymn several times as the closing chorale in his cantatas, here it is lent an emphatically joyful character that is highlighted by the soaring obbligato line of the piccolo flute.

Would you like to enjoy our videos ad-free? Subscribe to YouTube Premium now...

Workshop

Reflective lecture

Choir

Soprano

Susanne Frei, Guro Hjemli, Noëmi Sohn Nad, Noëmi Tran Rediger, Jennifer Rudin

Alto

Jan Börner, Olivia Fündeling, Katharina Jud, Alexandra Rawohl, Lea Scherer

Tenor

Marcel Fässler, Clemens Flämig, Raphael Höhn

Bass

Fabrice Hayoz, Philippe Rayot, William Wood

Orchestra

Conductor

Rudolf Lutz

Violin

Renate Steinmann, Martin Korrodi, Monika Altdorfer, Christine Baumann, Alessia Menin, Olivia Schenkel

Viola

Susanna Hefti, Martina Bischof, Emmanuel Carron

Violoncello

Maya Amrein, Martin Zeller

Violone

Iris Finkbeiner

Oboe

Luisa Baumgartl, Ingo Müller

Bassoon

Susann Landert

Trombone

Ulrich Eichenberger

Transverse flute

Claire Genewein

Flauto piccolo

Maurice Steger (special Guest)

Organ

Norbert Zeilberger

Harpsichord

Nicola Cumer

Musical director & conductor

Rudolf Lutz

Workshop

Participants

Karl Graf, Rudolf Lutz

Reflective lecture

Speaker

Iso Camartin

Recording & editing

Recording date

10/21/2011

Recording location

Trogen

Sound engineer

Stefan Ritzenthaler

Director

Meinrad Keel

Production manager

Johannes Widmer

Production

GALLUS MEDIA AG, Switzerland

Producer

J.S. Bach Foundation of St. Gallen, Switzerland

Librettist

Text

Chorale cantata by an unknown librettist, based on a hymn by Elisabeth Cruciger (Creutziger)

First performance

Eighteenth Sunday after Trinity,

8 October 1724

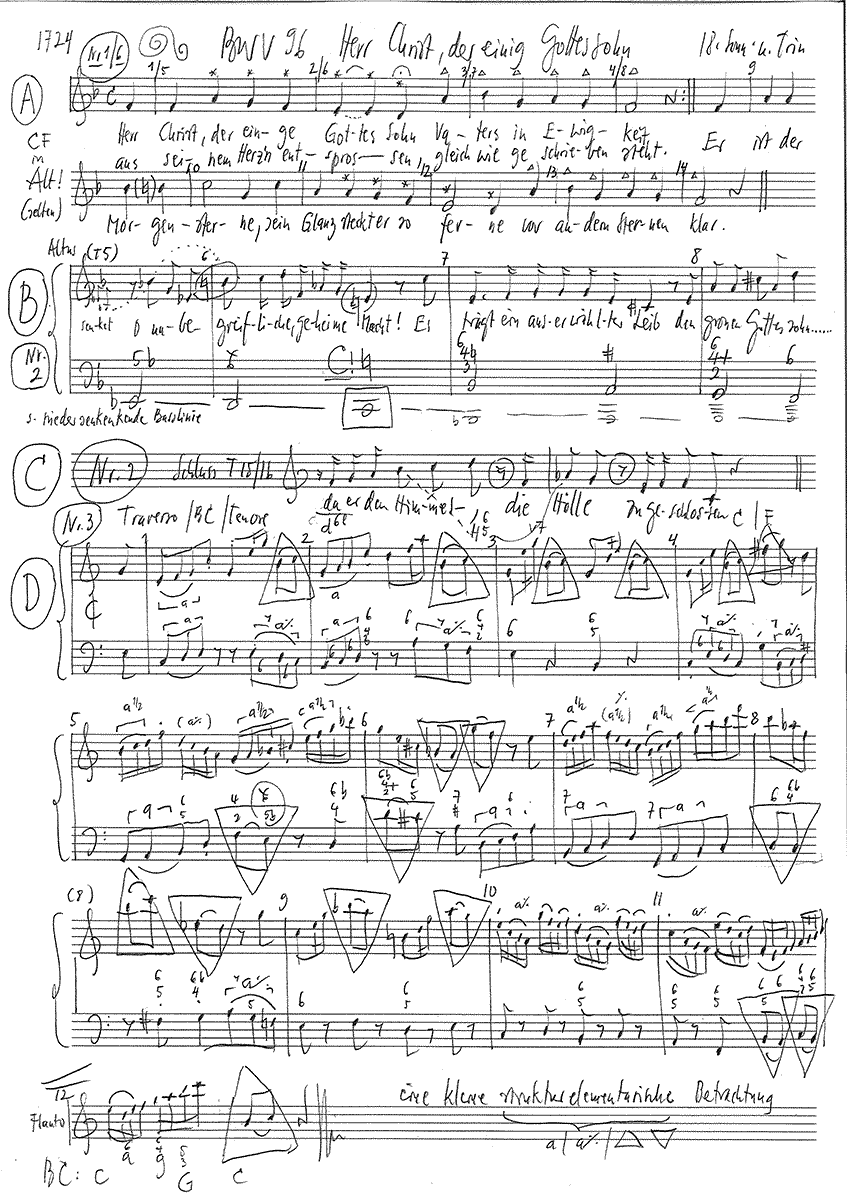

In-depth analysis

Cantata 96 on Elisabeth Cruciger’s hymn “Herr Christ, der einge Gottessohn” (Lord Christ, the only son of God) opens with an introductory chorus in a style reminiscent of Christmas music; the charming pastoral scene is set in a lively 9/8 metre that is propelled forward by the light, yet accented gestures of the string, oboe and continuo lines. Although Bach used this earnest hymn several times as the closing chorale in his cantatas, here it is lent an emphatically joyful character that is highlighted by the soaring obbligato line of the piccolo flute. The high and clear timbre of this instrument, although seldom used by Bach, bestows on the score a sweetness that calls to mind the amorous call of a courting songbird (perhaps more blackbird than the proverbial dove of the New Covenant) or the radiant twinkle of the morning star in the heavens. Within this airy structure, the choir parts are inserted in a style typical of Bach’s chorale cantata cycle: while the soprano, tenor and bass parts imitate the swinging orchestral rhythms, the cantus firmus is presented in the alto voice – a scoring that in this movement also reflects the reference to God’s “heart descended”. The corno da tirarsi, a type of horn built with a slide to increase the range of available notes, doubles the alto melody; in a later version, this part was rescored for alto trombone.

The following recitative is assigned to the alto, who sings in a stately and hymnal tone of the “wondrous power” of God’s love for the world as represented through the birth of Jesus Christ, a theme that both librettist and composer render in glorious sounds and images.

In the tenor aria, the piccolo flute is replaced by the transverse flute – a switch that underscores the versatility of Bach’s ensemble of town musicians, casual players and students. Indeed, although these players did not avail of the specialised skills of a virtuoso Hofkapelle, they were certainly competent in a variety of roles. The music here is typical of transverse flute parts – more a light-hearted gig than a leisurely pastorale – and in a style so strongly reminiscent of cantata BWV 180 “Schmücke dich, o liebe Seele” that it appears almost formulaic. Both pieces can be interpreted as an invitation to communion – which indeed is nothing other than the sacramental expression of the love revealed by the life of Jesus. Here, the “drawing close” of the “bonds of affection” is effectively evoked by sighing gestures and long, weaving figures; these intensify in the emphatic middle section to reflect the text “Grant that it with holiest passion grow ardent”. As with the introductory movement, the solo instrumental part of this aria was reassigned in a later version, this time to the violino piccolo.

The soprano recitative presents a humble plea for enlightenment and guidance on the path of life – a theme that is then explored in the bass aria, which is fittingly given a through-composed (rather than da-capo) form. In this movement, Bach literally interprets the text of “To the right side, to the left side, Wend their way my wayward steps” through alternating blocks of strings and oboes that increasingly unsettle the vocalist. This precarious game of juggling with failure – cleverly evoked by a minuet suggestive of the slippery world of the court – gives way at the words “Walk with me, my Saviour, still” to an intensified style that accompanies the cantabile plea with pressing orchestral chords. At the closing line “Let me not in peril falter”, however, the “left-right” motive of the opening bars is resumed: danger and confusion remain ever-present, and despite all godly protection, the path to the gates of heaven remains arduous.

After this contemplative aria in D minor, the earthy F tonality of the closing chorale represents a marked change of tack. In this setting, the early Reformation hymn unfurls the magic of might and ancient days, which is highlighted with celestial ease by the doubling of piccolo flute in the upper octave and thus attains an effect that is gentle and consoling.

Libretto

1. Chor

Herr Christ, der einge Gottessohn

Vaters in Ewigkeit,

aus seinem Herzn entsprossen,

gleichwie geschrieben steht,

er ist der Morgensterne,

sein’ Glanz streckt er so ferne

vor andern Sternen klar.

2. Rezitativ

O Wunderkraft der Liebe,

wenn Gott an sein Geschöpfe denket,

wenn sich die Herrlichkeit

im letzten Teil der Zeit

zur Erde senket.

O unbegreifliche, geheime Macht!

Es trägt ein auserwählter Leib

den großen Gottessohn,

den David schon

im Geist als seinen Herrn verehrte,

da dies gebenedeite Weib

in unverletzter Keuschheit bliebe.

O reiche Segenskraft! So sich auf uns ergossen,

da er den Himmel auf-, die Hölle zugeschlossen.

3. Arie

Ach ziehe die Seele mit Seilen der Liebe,

o Jesu, ach zeige dich kräftig in ihr.

Erleuchte sie, daß sie dich gläubig erkenne,

gib, daß sie mit heiligen Flammen entbrenne,

ach würke ein gläubiges Dürsten nach dir.

4. Rezitativ

Ach führe mich, o Gott, zum rechten Wege,

mich, der ich unerleuchtet bin,

der ich nach meines Fleisches Sinn

so oft zu irren pflege,

jedoch gehst du nur mir zur Seiten,

willst du mich nur mit deinen Augen leiten,

so gehet meine Bahn

gewiß zum Himmel an.

5. Arie

Bald zur Rechten, bald zur Linken

lenkt sich mein verirrter Schritt,

gehe doch, mein Heiland, mit,

laß mich in Gefahr nicht sinken,

laß mich ja dein weises Führen

bis zur Himmelspforte spüren.

6. Choral

Ertöt uns durch dein Güte,

erweck uns durch dein Gnad;

den alten Menschen kränke,

daß er neu Leben hab

wohl hier auf dieser Erden,

den Sinn und all Begierden

und Gdanken habn zu dir.

Iso Camartin

“In Ropes of Love”

About “leading”, “being pulled” and the ropes of life to be defended.

What a great woman, this Elisabeth Cruciger, wife and housewife of Luther’s pupil Caspar Cruciger! She was probably the first Protestant song poet ever. The song she wrote contains key words that encourage reflection. One could, for example, explore cosmologically what is hidden behind the “morning star” that stretches its shine far away, “clear before other stars”. – One could also ponder what this woman, first a good nun, then a courageous wife, might have meant by “in the last part of time” – that is, with the conviction that as a Christian one lives in an end time and has to survive in it. Another variant would be to speculate on what a religious faith would have to look like, which one also has to experience as a “sweetness in the heart”. And the meaning of the sentence in the final stanza: “Kill us through your goodness” deserves more than just musing about what has to die in us so that we not only become somewhat godly, but also a little happy already in this life. This Elisabeth also has it in her!

I choose none of these themes, however, but a cue that we owe to the unknown arranger of the hymn to the cantata text. in the first aria, the tenor singer asks Jesus to draw his soul to himself “with cords of love”. And in the recitative that follows, the soprano’s plea is: “Oh lead me, O God, to the right path.” My reflection, therefore, has to do with “leading”, “being drawn”, and with the ropes of life to be defended.

Let us begin with “leading”. Everyone talks about leadership. No member of management is hired today without first having his or her leadership skills tested in an assessment. Of course, leaders are often dubious characters. The world has had the most terrible experiences with leaders and dukes, with party capos and caudillos – and even those supposedly charismatic leaders like Napoleon left destruction and misery in their wake and were strangely unsuitable as bringers of happiness and peacemakers. So let us beware of leaders, the self-proclaimed ones and those whom the crowds cheer. Nietzsche had some wise things to say about the ambivalence of the leadership business, alternating between the cold exercise of power and the warm seduction of propaganda and enticing promises. I will quote just one of his thoughts on the claim to leadership: “He who fights with monsters may take care not to become a monster in the process. And if you look long into an abyss, the abyss also looks into you.” (“Beyond Good and Evil” ii, p. 636) Thus, it is the duty of an enlightened citizen to maintain scepticism and distance towards those who become monsters and abysmal misanthropes through leadership magic.

But may one make God one’s leader? A religious person would not hesitate to give his consent because God seems to him to be the most trustworthy being there is. But trust is one thing. It is a risky advance, a gamble that is ultimately difficult to justify, an advance investment in good faith. Not everyone is prepared to make such advance investments! Today, bankers and CEOs are experiencing just how quickly trust can be lost, as are doctors and priests. And once this trust is gone, no one knows if and when it will return. “Life has made me distrustful!” is a statement that is as common as it is sad, and even well-meaning spouses can sing more than one song about it. Only children are completely trusting, but only as long as life has not yet violated their expectations. The adult human being is shaped by experience and as a rule is not trusting, but rather fickle. “Soon to the right, soon to the left, my stray step steers.” Bach miraculously set this indecisive back and forth from one position to another in sound. Did you notice how the strings and wind instruments went at it in the bass aria? How they competed against each other in three-four time to win the wavering one over to their side and for themselves? Strange dance steps of an uncertainly advancing figure are presented to us. Is the errant one being pulled, or perhaps rather pushed? And the voice of this lost one: sometimes it rises and sometimes it sinks, as if life were a swaying boat on metre-high waves. As if there were dangerous whisperers in the background, calling out to the doubter: Come to me! No, to me you shall come! Someone no longer knows how to get in and out. Only one thing remains in this situation: “Do not let me sink in danger!” the voice begs, and: “Go, my Saviour, with me!” Only the God-believing person who puts his trust in a single card may ask in this way: God will not let his creature sink into the abyss, but will lead it upwards – “to the gates of heaven”. The music miraculously demonstrates this to us through falling and rising movements. We are in the midst of it: swaying and swaying, rising and falling, and urgently need someone to show the way.

Another remarkable phrase is found in the cantata text: “Will you only guide me with your eyes.” What is the best way to imagine this? Does trust mean closing one’s own eyes and surrendering oneself to the eyes of others? Is blind trust required in life in order to reach the right destination? The well-known painting “The Fall of the Blind” by Pieter Bruegel the Elder comes to mind. Bach certainly knew the passage from the New Testament in Matthew where it says: “But if one blind man leads another, they both fall into the pit.” (Matthew 15:14) There must be an alternative to the home stretch to ruin. The admonition is clear: we should entrust ourselves to the seeing, not the blind. On icons of the Eastern Church, one often sees figures who seem to be searching for something with their eyes: namely, the eyes of the Saviour awaiting them in heaven. As if they had to fall under the spell of better eyes than their own! We also know from people in love what an illumination of their being it is when they can finally look into the eyes of their beloved. Loving eyes exert a strange pull on the other person, one is magically attracted to them. This brings us to that special kind of guidance that one almost has to call seduction. A seduction through magical attraction. This means, however, that our task cannot be to go through the world with our eyes closed and fall into the pool like Bruegel’s blind beggars, but to seek the right goal with our eyes open. i read this “leading with your eyes” as a call to the wavering human being to set his eyes on the right goal. To walk towards the goal eye to eye, as it were.

The image of the “ropes of love” from the tenor aria, with which the soul is to be pulled to the place that is advantageous for it, fits in with this. Love, as we know, is not the only power that can draw us to itself. In certain life situations, there are far stronger ropes that keep us on our toes. The hunger for power, for influence, for money, for visibility, for prestige, for recognition of even the most ridiculous kind – this hunger often has the thicker ropes and the stronger pull than love. Ambition is a powerful traction rope – we see it well in times when elections are around the corner. Greed also has pulling forces that one does not suspect. Those who are pulled through life by it easily lose their sense of justice and their sense of the right measure. But social envy can also take us in its grip and pull us into the abyss of hatred, so that all we want to do is get even and take revenge on those whom we heartily envy their position and wealth. Cornered by our own failures, bad luck and misfortune, we quickly find ourselves entangled in terrible rope teams that make us bitter and vengeful.

There is something dubious about rope teams anyway. There is a distinct smell of cronyism and collusion, of collusion and intrigue. One hand washes the other. At the banks, who can see through that? In the churches, who knows what’s going on? One can only raise one’s arms and wish: May life protect us from sinister cords!

Of course, the “ropes of love” have to be imagined quite differently. And those of mutual goodwill, too. There is no compulsion or coercion – they are ropes that move and accelerate more than they bind. The tenor aria with the flute solo shows how this pulling is to be imagined: as if the soul were being taken in the arm in a friendly way and moved in the right direction, powerfully and decisively, but the rope that is used here is more a kind of play rope with which one is included in a moving swing that moves one away from the place and towards the goal. The flute figure with the soaring semiquavers, which are caught again and again on the note b, as if the rope of love were catching every exuberance of happiness and every caprice of mood, lets us feel it exactly: The ropes of love are nothing but the wings of freedom. Go on, go on! Nothing will happen to you! You are well on your way!

But where does this power come from that attracts us and draws us to itself in such a way? The wondrous opening chorale of the cantata – for me one of the most beautiful among the many incomparable ones belonging to the 2nd Leipzig volume of choral cantatas – leaves no doubt about this for the Christian: it is the “Lord Christ, the Son of God who has come in”, who is, so to speak, the centripetal force of the universe of faith and who is to force us under the spell of his power and his love. But such theological statements have something dogmatically hard and inexorable about them, which remains in need of clarification and must first be made appropriate for the human imagination through convincing imagery. Theological truths must not remain in cold logical nakedness, but must be clothed in images that enlighten and warm our imagination. And the image for this dark matter, for this black energy of the uncannily attractive kind, is an entirely luminous one and bears the following name: “He is of the morning stars, / his’ shine he stretches so far / clear before other stars.” No wonder that this cantata has also been associated with Epiphany, 6 January, when the three wise men from the east, following the bright star, paid their respects to the new king of the world. Even our astrologically blissful present day believes that stars exert special powers of attraction. Light not only attracts moths, it also exerts an irresistible pull on people.

Bach’s musical approach to making this irresistibility audible and perceptible in the pull of a star is almost miraculous: for one thing, he chooses a Sicilian rhythm, a type of progression based on triple figures – in our case, a nine-eighths time – to characterise this seemingly unstoppable inner urge to move towards a goal. You can’t help but join in, stride along, pull along, even dance along, so much does this time signature take our basic musical feeling by the sleeve and set us involuntarily in motion. When Bach wrote the cantata “They will all come from Saba” for Epiphany in the same year, 1724, he did the same as when he described the procession of the three kings with their gifts, only here he chose the Siciliana bar with twelve instead of nine quavers. But it gives the striding procession the same gait. Ever since I became familiar with these two opening movements of Bach’s cantatas, I have known that camels only move in the sicilian rhythm when they have found their desert trot. Camels rarely have beautiful voices, but their gait is one of the most musical found in the animal kingdom, and Bach understood like no other how to make the sicilian gait audible to us in the genus Camelidae Tylopoda, i.e. the hump-bearing callosal. It is almost impossible to walk along more beautifully than in this upbeat triple rhythm, which gives those who remain in its motion an irresistibly purposeful gait towards an oasis of happiness. Let’s trust the rhythm of the camels!

But that is not all. In order to make us feel the mysterious glow, the flickering and sparkling of the morning star in an almost sensual way, Bach added a flauto piccolo, a recorder, to the usual instruments of the orchestra with oboes, a horn, strings and the continuo group – and expected the player to do everything that one may do with a virtuoso. We don’t know whether the piccolo player of the time was really as unbelievably good as Maurice Steger is tonight, but he must have been good too, otherwise Bach certainly wouldn’t have expected this kind of difficulty of him. For what else did he want to achieve than that we be amazed: before the sparkling brilliance and the luminous magic of that star which not only leads and guides us on the right path, but in whose attraction we ourselves are virtually transformed. for in this movement, quite strange musical shifts and dislocations occur. At first, we feel at ease in a familiar F major and related keys, until suddenly things happen that push us into what the Austrian author Robert Musil would have called “the other state”. Suddenly a jolt – and we are in a different perceptual world, in a hitherto alien zone. Something has enraptured and maddened us – what is meant is the thrust that Bach plans for the words “er ist der Morgensterne” in bar 90 – you don’t need to count the bars, it is enough to suddenly experience the irruption of the unexpected and unfamiliar, as if the harmonic ground were suddenly quaking beneath our feet and as if for a second there were something like a musical free fall. Bach is always good for surprises, but here he catches us on the wrong foot!

With this thought, I would like to conclude my short reflection here. Great art perhaps has something in common with religious experience in that it first sets us trotting and then – often at a completely unexpected point – at the given moment sometimes gently, then again shockingly throws us off the trot. We are not beasts of burden who settle into a Sicilian rhythm as we walk through life and are allowed to resign ourselves to it. We need the wake-up call now and then that brings us “the other state”. When people complain today that religion no longer has the goal-oriented power it may have had in earlier generations – and certainly in Bach – the complaint alone does not help much. Most of us only think about whether we are on the right track in life when we find ourselves in a crisis. But it could be that you don’t have to fall blindly into the pit before you wake up, open your eyes and become aware of the wrong track. Because something has certainly not changed: Although today many artificial lights and Bengal fires distract us from the essential, the morning star has not yet ceased to shine. But if you want to see it and follow it, you have to open your eyes – and let yourself be pulled by the ropes of light. in this rope of light, you can still travel quite unerringly today.

This text has been translated with DeepL (www.deepl.com).