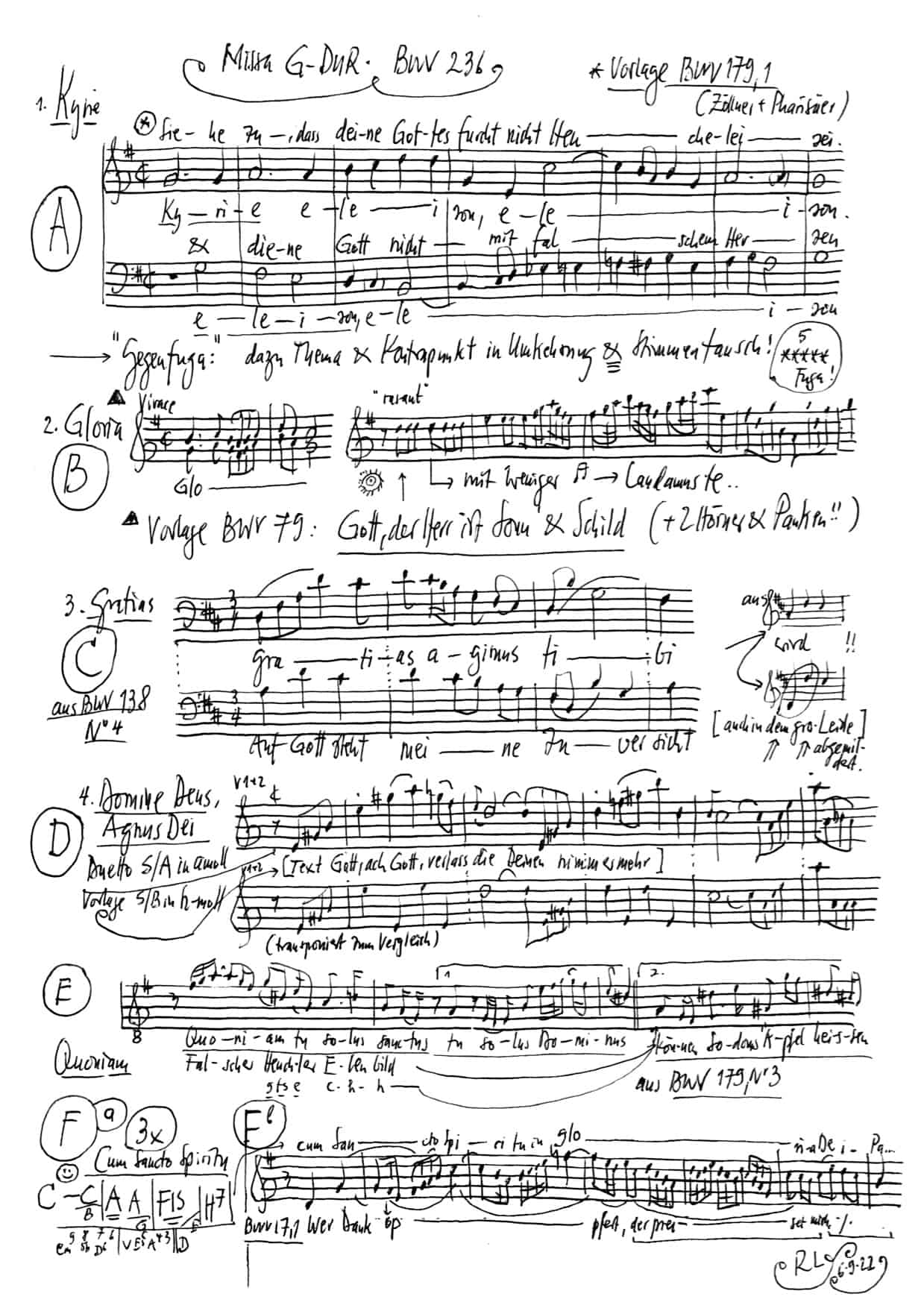

Messe G-Dur

BWV 236 //

(Mass in G major) for soprano, alto, tenor and bass, vocal ensemble, oboe I+II, strings and basso continuo

Would you like to enjoy our videos ad-free? Subscribe to YouTube Premium now...

Workshop

Reflective lecture

Choir

Soprano

Lia Andres, Maria Deger, Noëmi Sohn Nad, Noëmi Tran-Rediger, Alexa Vogel, Ulla Westvik

Alto

Laura Binggeli, Antonia Frey, Stefan Kahle, Lea Pfister-Scherer, Lisa Weiss

Tenor

Manuel Gerber, Klemens Mölkner, Christian Rathgeber, Sören Richter

Bass

Daniel Pérez, Philippe Rayot, Julian Redlin, Peter Strömberg, Tobias Wicky

Orchestra

Conductor

Rudolf Lutz

Violin

Eva Borhi, Lenka Torgersen, Peter Barczi, Christine Baumann, Petra Melicharek, Dorothee Mühleisen, Ildikó Sajgó, Judith von der Goltz, Cecilie Valtrova

Viola

Sonoko Asabuki, Matthias Jäggi, Rafael Roth

Violoncello

Maya Amrein, Daniel Rosin

Violone

Markus Bernhard

Oboe

Philipp Wagner, Andreas Helm

Bassoon

Gabriele Gombi

Harpsichord

Thomas Leininger

Organ

Nicola Cumer

Musical director & conductor

Rudolf Lutz

Workshop

Participants

Rudolf Lutz, Pfr. Niklaus Peter

Reflective lecture

Speaker

Frank Jehle

Recording & editing

Recording date

16/09/2022

Recording location

St. Gallen (Switzerland) // Cathedral

Sound engineer

Stefan Ritzenthaler

Producer

Meinrad Keel

Executive producer

Johannes Widmer

Production

GALLUS MEDIA AG, Schweiz

Producer

J.S. Bach-Stiftung, St. Gallen, Schweiz

Libretto

Kyrie

1. Chor

Kyrie eleison,

Christe eleison,

Kyrie eleison.

Gloria

2. Chor

Gloria in excelsis Deo

et in terra pax hominibus

bonae voluntatis.

Laudamus te,

benedicimus te,

adoramus te,

glorificamus te.

3. Arie — Bass

Gratias agimus tibi propter

magnam gloriam tuam.

Domine Deus, Rex coelestis,

Deus Pater omnipotens,

Domine Fili unigenite Jesu Christe.

4. Arie — Duett: Sopran und Alt

Domine Deus, Agnus Dei,

Filius Patris, qui tollis peccata mundi,

miserere nobis,

qui tollis peccata mundi,

suscipe deprecationem nostram.

Qui sedes ad dextram Patris,

miserere nobis.

5. Arie — Tenor

Quoniam tu solus sanctus,

tu solus Dominus,

tu solus altissimus Jesu Christe.

6. Chor

Cum Sancto Spiritu

in gloria Dei Patris, amen.

Frank Jehle, Rev. Dr. theol., verlesen durch Dr. Konrad Hummler

Reflection on the occasion of the performance of the Mass in G major (BWV 236) by Johann Sebastian Bach on Friday, 16 September 2022, in the Cathedral of St. Gall

Dear Bach Community!

It is not a matter of course that I, as a Protestant Reformed theologian, am allowed to give a speech at a Mass. The papal mass is “a denial of the [all]one sacrifice and suffering of Jesus Christ” and therefore “a maledictory idolatry”, says the “Heidelberg Catechism”, one of the most famous confessional writings of the Reformed branch of Protestantism.[1] Introduced in the Electoral Palatinate in 1563, it was also declared binding in the Reformed Free Imperial City of St. Gallen in 1574.[2] The Roman Catholic Reform Council of Trent had already solemnly declared in 1562 – to a certain extent as a preventive measure – that “whoever says that the Sacrifice of the Mass blasphemes or detracts from the Most Holy Sacrifice of Christ, which was accomplished on the Cross, shall be condemned to anathema”.[3] And how aggressive it could sound on the Lutheran side is documented by the book title of the in his way important Tübingen theologian Jacob Andreae: “Spiegel der offenbaren unverschämbten calvinischen Lügen …”, from 1588.[4]

Today we shake our heads at such theological aggressiveness. And what makes it worse is that it did not remain a verbal dispute. I am thinking of the Parisian blood wedding, when on the night of 23-24 August 1572 – St Bartholomew’s Night – on the occasion of the marriage of Henry of Navarre to Margaret of Valois, three thousand Huguenots were murdered in Paris alone, and several thousand more in the countryside in the days that followed. The Protestant world was traumatised. However, the horrors also had a positive result, at least for the time being: so that he could become King of France, Henry of Navarre, who had a Reformed upbringing, converted to Catholicism 21 years after the Night of St Bartholomew. “Paris vaut bien une messe!” With this he put the confessional disputes into perspective. And as a consequence of this decision, he introduced religious tolerance in his kingdom. This was the announcement of a new era. Even though there were many setbacks (think of the Thirty Years’ War), people in Central Europe (and North America) learned to live with religious pluralism. With a shudder, however, we realise that even today this is not the case everywhere. (I am thinking not only of the precarious situation of members of Christianity in various countries, but also of the Jessids in Muslim Iraq and the Muslim Rohingyas in Buddhist Myanmar).

But to something else! Unfortunately, as a theologian, I have to say that the dispute between the Christian denominations has partly continued into the present, although fortunately mostly no longer by force of arms. I am now concentrating on German-speaking theology. It took, among other things, the Second World War and, in Germany, the experience that during the Hitler era Protestant pastors and Catholic priests had to share a cell with each other in prison or in a concentration camp, that there was a paradigm shift, especially in connection with the Mass and the Lord’s Supper. We theologians have learned to critically question the doctrines that have been handed down to us. And we realised that many things were based on misunderstandings. Differences between schools were considered absolute and insurmountable. At the most, it is about different emphases. The similarities and what really matters are much greater than the differences.

First, an abbreviation of the inner-Protestant development: A landmark was the Arnoldsheim Theses of 1958. A number of respected theologians (no women theologians at that time) agreed that Reformed and Lutherans should be allowed to celebrate the Lord’s Supper together. Some prominent Lutherans still resisted at that time. But in 1973 the time had finally come: in the so-called Leuenberg Agreement – signed on Leuenberg in Baselland – the communion of all Protestants was decided. The Evangelical Reformed Church of the Canton of St Gallen also joined this agreement. I quote from it:

“In the Lord’s Supper, the risen Jesus Christ, in his body and blood given for all, gives himself with bread and wine through his promising word. He thereby grants us forgiveness of sins and frees us to live a new life by faith. He lets us experience anew that we are members of his body. He strengthens us for service to others. – When we celebrate the Lord’s Supper, we proclaim the death of Christ, through which God has reconciled the world to himself. We confess the presence of the risen Lord among us. Rejoicing that the Lord has come to us, we wait for his future in glory.”[5]

Although this is only an internal Protestant agreement, it is also relevant for the relationship with the Roman Catholic Church. On the question of the presence of Jesus Christ in the Lord’s Supper, the former differences have almost disappeared. One only has to bear in mind that official Roman Catholic theology does not conceive of the presence of Jesus Christ in the Lord’s Supper in such a materialistic way as was occasionally thought in the past. “[…] the Eucharistic reality exists after the manner of the Spirit”, formulated the then leading (and by no means “progressive”) Catholic dogmatist Michael Schmaus as early as 1964.[6] And Joseph Ratzinger, later Pope Benedict XVI, wrote in 1969:

“Physically and chemically nothing happens through the Eucharist. But faithful adherence to reality includes at the same time the conviction that physics and chemistry do not exhaust the whole of being, so that it cannot be said that where nothing happens physically, nothing happened at all.[7]

There is a clear convergence between Protestant Reformed, Evangelical Lutheran and Roman Catholic understandings of the Lord’s Supper.

But something completely different in conclusion: as a Protestant Reformed theologian, I would like to make a declaration of love for the traditional text of the Mass. If we put the theological arguments about the Mass and the Lord’s Supper to one side and stick only to the texts themselves, we find that they do indeed have an interdenominational character. With the Kyrie eleison and the Gloria in excelsis (these are what we are concerned with today, since the work performed today, as a so-called Missa brevis, only sets these movements to music), we participate in an ecumenism that goes back to antiquity. In part, individual formulations even go back to pre-Christian Judaism. And: “Kyrie eleison” (“Lord, have mercy”) is what the people used to call out to the Roman emperors, to whom they attributed divine nature with this address. “If the congregation addressed this call [but] to Jesus Christ, whose presence they thereby confessed, and if they thereby withdrew the call from the emperor, this was on the same line as the refusal of sacrifice and other elements of the high treason of which Christians were accused.”[8] This was tantamount to a – non-violent – revolution.

The Kyrie is not only a confession of sin, but also a comprehensive “plea for help and mercy in all human need”.[9] The pilgrim Egeria, who came from what is now France, heard the Kyrie in a service in Jerusalem towards the end of the fourth century and was deeply moved by it.[10] And still today: by praying “Kyrie eleison”, we come before the triune God as those who are aware at this moment that we cannot live without him, but are dependent on him skin and hair. The Berlin theologian Friedrich Schleiermacher described God in a successful formulation as the “whence” of our “schlechthinnige Abhängigkeit”.[11]

And now for the Gloria: In this “hymnus angelicus” we join in a concert of heaven. You remember: In the Christmas story in Luke’s Gospel, the heavenly hosts sing: “Glory to God in the highest, and on earth peace, and goodwill towards men”, as the now classic Luther Bible translates.[12] The Gloria is an elaborate version of this hymn of praise by the angels and can be found in its present form in manuscripts from the 5th century.[13] Originally it was part of the Liturgy of the Hours in oriental monasticism.[14] Today, we are part of an ancient ecumenical tradition.

Dear Bach Community!

As a Protestant Reformed theologian, I can unreservedly join in this concert of heaven. I look forward to hearing it a second time this evening – including the Kyrie.

[1] Cf. The Heidelberg Catechism. Edited by Otto Weber. Hamburg 1963, p. 45.

[2] Cf. “Ain christliche Underwisung der Jugend im Glouben”, Der St. Galler Katechismus von 1527, edited by Frank Jehle, Zurich and St. Gallen 2017, p. 48.

[3] Heinrich Denzinger: Kompendium der Glaubensbekenntnisse und kirchliche Lehrentscheidungen. Improved, expanded, translated into German and edited with the collaboration of Helmut Hoping by Peter Hünermann. 37th edition. Freiburg im Breisgau and other places 1991, p. 566.

[4] Jacob Andreae: Spiegel der offenbaren unverschämbten calvinischen Lügen, gegen reine Lehrer der Augspurgischen Confession, Vnnd grewlichen erschröckenlichen Blasphemungen, gegen die Göttliche Maiestat der Menschheit Jesu Christi. To all pious Christians for a faithful warning to beware of this spirit. Tübingen 1588.

[5] In: Valid decrees of the Evangelical Reformed Church of the Canton of St. Gallen 14-41, paragraphs 15 b, 18 and 19.

[6] Michael Schmaus: Katholische Dogmatik IV, I. Sechste, umgearbeitete und erweiterte Auflage. Munich 1964, p. 351.

[7] Joseph Ratzinger in: Theologisches Jahrbuch. Gütersloh 1969, p. 295 f.

[8] Dietrich Schuberth in: TRE 18. Berlin and New York 1989, p. 652,

[9] Christhard Mahrenholz: Kompendium der Liturgik. Kassel 1963, p. 94.

[10] William T. Flynn in: RGG, 4th edition, vol. 4. Tübingen 2001, sp. 1919.

[11] Cf. Friedrich Schleiermacher: Der christliche Glaube nach den Grundsätzen der evangelischen Kirchen im Zusammenhang dargestellt. Edited by Martin Redeker. First volume. Berlin 1960, pp. 23-30.

[12] Lk 2, 14, Luther Bible from 1912.

[13] Hans-Christoph Schmidt-Lauber in: TRE 11. Berlin and New York 1983, p. 267.

[14] Friedrich Kalb in: TRE 21. Berlin and New York 1991, p. 371.

This text has been translated with DeepL (www.deepl.com).