Was Gott tut, das ist wohlgetan

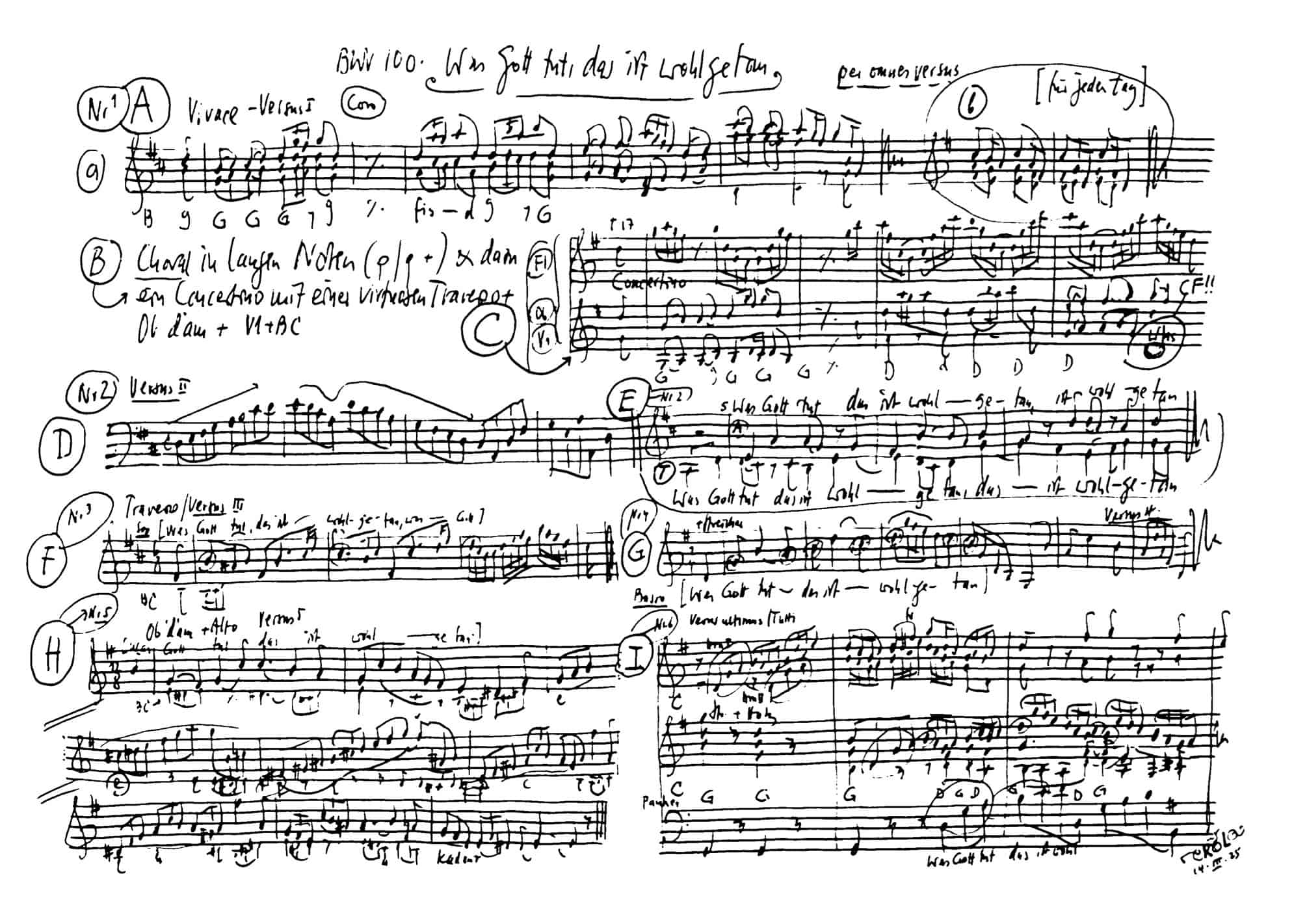

BWV 100 // Unspecified occasion

(What God doth, that is rightly done) for soprano, alto, tenor and bass, vocal ensemble, horn I+II, timpani, transverse flute, oboe, strings and basso continuo

Place of composition in the church year

Pericopes for Sunday

Pericopes are the biblical readings for each Sunday and feast day of the liturgical year, for which J. S. Bach composed cantatas. More information on pericopes. Further information on lectionaries.

Would you like to enjoy our videos ad-free? Subscribe to YouTube Premium now...

Workshop

Reflective lecture

Choir

Soprano

Maria Deger, Linda Loosli, Stephanie Pfeffer, Susanne Seitter, Noëmi Tran-Rediger, Ulla Westvik

Alto

Antonia Frey, Simon Savoy, Lea Scherer, Lisa Weiss, Sarah Widmer

Tenor

Marcel Fässler, Achim Glatz, Christian Rathgeber, Berthold Schindler

Bass

Jean-Christophe Groffe, Fabrice Hayoz, Israel Martins, Philippe Rayot, William Wood

Orchestra

Conductor

Rudolf Lutz

Violin

Éva Borhi, Péter Barczi, Christine Baumann, Petra Melicharek, Ildikó Sajgó, Lenka Torgersen

Viola

Martina Bischof, Matthias Jäggi, Sarah Mühlethaler

Violoncello

Maya Amrein, Daniel Rosin

Violone

Markus Bernhard

Traverse flute

Marc Hantaï

Oboe

Andreas Helm

Bassoon

Gabriele Gombi

Horn

Stephan Katte, Thomas Friedlaender

Timpani

Inez Ellmann

Harpsichord

Thomas Leininger

Organ

Nicola Cumer

Musical director & conductor

Rudolf Lutz

Workshop

Participants

Rudolf Lutz, Pfr. Niklaus Peter

Reflective lecture

Speaker

Paul Hoff

Recording & editing

Recording date

25/04/2025

Recording location

Trogen (AR) // Evang. Kirche Trogen

Sound engineer

Stefan Ritzenthaler

Producer

Meinrad Keel

Executive producer

Johannes Widmer

Production

GALLUS MEDIA AG, Schweiz

Producer

J.S. Bach-Stiftung, St. Gallen, Schweiz

Librettist

First performance

Around 1732

Text

Samuel Rodigast, 1676/1677

Libretto

1. Chor

Was Gott tut, das ist wohlgetan,

es bleibt gerecht sein Wille;

wie er fängt meine Sachen an,

will ich ihm halten stille.

Er ist mein Gott,

der in der Not

mich wohl weiß zu erhalten;

drum laß ich ihn nur walten.

2. Duett – Alt, Tenor

Was Gott tut, das ist wohlgetan,

er wird mich nicht betrügen;

er führet mich auf rechter Bahn,

so laß ich mich begnügen

an seiner Huld

und hab Geduld,

er wird mein Unglück wenden,

es steht in seinen Händen.

3. Arie — Sopran

Was Gott tut, das ist wohlgetan,

er wird mich wohl bedenken;

er, als mein Arzt und Wundermann,

wird mir nicht Gift einschenken

vor Arzenei.

Gott ist getreu,

drum will ich auf ihn bauen

und seiner Gnade trauen.

4. Arie – Bass

Was Gott tut, das ist wohlgetan,

er ist mein Licht, mein Leben,

der mir nichts Böses gönnen kann,

ich will mich ihm ergeben

in Freud und Leid!

Es kommt die Zeit,

da öffentlich erscheinet,

wie treulich er es meinet

5. Arie – Alt

Was Gott tut, das ist wohlgetan,

muß ich den Kelch gleich schmecken,

der bitter ist nach meinem Wahn,

laß ich mich doch nicht schrecken,

weil doch zuletzt ich werd ergötzt

mit süßem Trost im Herzen;

da weichen alle Schmerzen.

6. Choral

Was Gott tut, das ist wohlgetan,

darbei will ich verbleiben.

Es mag mich auf die rauhe Bahn

Not, Tod und Elend treiben,

so wird Gott mich

ganz väterlich

in seinen Armen halten;

drum laß ich ihn nur walten.

This text has been translated with DeepL (www.deepl.com).

Paul Hoff

1. Background

My reflections on this Bach cantata are based on more than four decades of psychiatric and psychotherapeutic work. You may ask where the connection lies between a Bach cantata that is almost 300 years old and embedded in a theological context on the one hand, and today’s medical treatment of people in life crises and mental illness on the other. In preparing for this reflection, I asked myself this question too, and to be honest, I was a little concerned at first. But I soon found an answer that seemed all the more convincing the more I immersed myself in the music and text, despite being a theological and musical layman.

This answer has to do with what we in the medical profession – and here perhaps especially in psychiatry – can learn from our patients if we look closely enough. It is about the tensions and contradictions that we all face in our lives, which we cannot avoid, no matter how much we would like to. Here, in enduring, shaping and, at best, resolving difficult situations, uncertainties and contradictions, I see the substantive bridge between what therapeutic work can achieve and what Bach presents us with in this cantata in music and lyrics.

2. Therapy as an interpersonal relationship

Whether mentally healthy or ill, we are all connected by the human condition, that which makes us human and distinguishes us from animals and inanimate objects. We question and doubt, we act and hesitate, we decide and worry about the consequences. This applies to the ‘big’ questions such as ‘Who am I?’, ‘To whom and to what do I devote my life?’, ‘Is there protection if I find myself in a crisis, if the ground is pulled out from under my feet?’, ‘Is it even worth asking such questions, or am I not helplessly at the mercy of the world and fate anyway?’ However, it also applies to the ‘smaller’, everyday questions that require decisions.

When we find the balance between all these challenges, we are fortunate enough to feel ‘at home’ in our own lives, a state we can call mental health. But as we all know, this is not always the case. In times of crisis and illness, many questions come to the surface with particular force.

People with mental illness often confront us (and, of course, themselves) in an impatient, sometimes even relentless manner with radical, existential questions. This can lead to serious, even distressing conversations. A severely depressed patient who was drowning in anxiety and guilt recently asked me what on earth a weak and flawed person like her was still doing in this world. Although she did not address it directly, the suicidal undertone was unmistakable.

However, it can also be completely different: I will never forget the question accompanied by a serious smile that a man suffering from schizophrenia confronted me with. Although I had known him for more than ten years at that point, it took me completely by surprise. The seriously ill patient suffered from paranoia and tormenting hallucinations. He abruptly interrupted our conversation and asked in a raised voice: ‘Where do you get the damn certainty, Mr Hoff, that I’m crazy – and not you?’ And, as if to show that he wasn’t joking, he added: ‘Have you ever seriously considered whether your world is as clear, as certain, as self-evident as you think it is?’

Don’t get me wrong: this patient, a sophisticated, intelligent man, knew perfectly well that he was not well, that he needed help and that I was trying to give him that help. That wasn’t the point. What bothered him, perhaps even hurt him, was his impression of a simple division of roles: here he was, the insecure sick person who thinks, says and perceives nonsensical things, and there was the world of the healthy, the ‘normal’ people who have no need for doubt because they are, by definition, right – a world represented by me, no less. The fact that he bluntly addressed the risk, indeed the falsity, of such a crude simplification, albeit ironically, gave me (and still gives me) a lot to think about. I learned something from this patient.

Now, it is not the primary goal of psychotherapy for the therapist to learn as much as possible. The goal is for the person affected to feel better in the long term. But how can this be achieved?

At the heart of this is a sustainable therapeutic relationship. It is the foundation for helping a person affected by crisis or illness to regain their ability to make decisions and take action, to make autonomy livable for them again. However, this cannot be a one-way street. It is not about an external object, nor is it about the mere transfer of information; it is about people – typically two interacting people, the patient and the therapist. Successful therapy is therefore always a dialogical negotiation process. It mediates between poles that initially appear irreconcilable, such as despair and hope, fear and courage, suicidal tendencies and the will to live – and, in the best case, points to new, viable paths.

Here we are already moving into the realm of our cantata, even if it may not seem so to you (just as it did not to me during my preparation).

3. BWV 100: On trust in relationships

For it is precisely this ability to negotiate the seemingly irreconcilable, to act in difficult, desperate situations, that is addressed by the cantata we have heard this evening and will soon hear again.

The text – and even more so the music – give no cause for fatalism or complacent complacency. The messages conveyed by the cantata are not: ‘I can’t do anything anyway because God controls everything’ or ‘I don’t have to do anything, I don’t have to take responsibility because God will take care of everything’. On the contrary: as I read it, its message is almost reminiscent of the courageous and demanding appeal of the great Enlightenment philosopher Immanuel Kant, who was born almost forty years after Bach and whose 300th birthday we celebrated in 2024: ‘Sapere aude!’ he urged us. ‘Have the courage to use your own understanding!’

I have chosen three perspectives to show that the text of the cantata does indeed convey such a courageous and encouraging message.

Perspective 1: We can and should act for ourselves

‘Drum lass‘ ich ihn nur walten’ (‘So I let him rule’) is the line in the first verse, while the fifth verse speaks of a ‘chalice … that is bitter according to my delusion’. So, as the person concerned, I am involved myself, I am actively participating: I allow something to happen; it is about ‘my delusion’, my fear, my addiction. Not everything has already been decided by God. Rather, I am called upon to decide whether I allow something to happen – or not.

Perspective 2: Trust is possible, but it is mutual

‘He will not betray me’ (in the duet in the second verse), “will not pour poison into my medicine” (in the soprano aria in the third verse): betrayal and poisoning are possible, at least conceivable; the text leaves it open. But I trust that it will not happen, that God will not do it.

The double designation of God as ‘my doctor and miracle worker’ in this verse is impressive, even if it seems a little strange to us today at first glance. But trust is not a monolith, but something multi-layered. It does not require complete, conclusive knowledge, not even in therapy. Question marks and uncertainties are allowed to remain. Clear, predictable medical behaviour – the rational element, as it were – naturally promotes healing. But improvement can also occur without every single step being explainable. It just happens. There are moments like this in every treatment. The image of the ‘healer’ could refer to such experiences – and would then no longer be as mysterious and irrational as it may seem at first, but rather encouraging.

Perspective 3: Dialogue as part of social interaction

The fourth verse, the bass aria, ends with the lines ‘The time will come when it will be revealed how faithful he is.’ I interpret this as opening up the personal and dialogical field to the social dimension: When I act, enter into dialogue with another person – or, in theological terms, with God – this always has something to do with my environment – sooner or later, because ‘the time will come’. In other words, we are not isolated monads. The private sphere is always interwoven with the social sphere, with the ‘public sphere’, as the cantata calls it. This also applies to psychotherapeutic work.

And the essence of the three perspectives? The cantata does not want to lead us to fearful, dishonest conformity, nor to resigned passivity, nor to defiant, arrogant insistence on our own point of view and our own possibilities. Rather, it calls on us to actively enter into relationships, to take risks – and to trust.

4. My personal conclusion

In today’s topic, questions about the nature of human beings, the fundamentals of therapeutic action and Bach’s magnificent music flow together to form a common picture, which I would like to describe as follows: As a person, I inevitably and constantly come up against limits, including painful and distressing ones. However, this does not rob me of my ability to trust. Trust, in turn, in others and in myself, is a prerequisite for being able to act and take responsibility for my actions.

Now, like you, I look forward to revisiting Bach’s cantata ‘Was Gott tut, das ist wohlgetan’ with a new perspective, perhaps accentuated by our joint reflections, and I thank you very much for your attention.