Nimm von uns, Herr, du treuer Gott

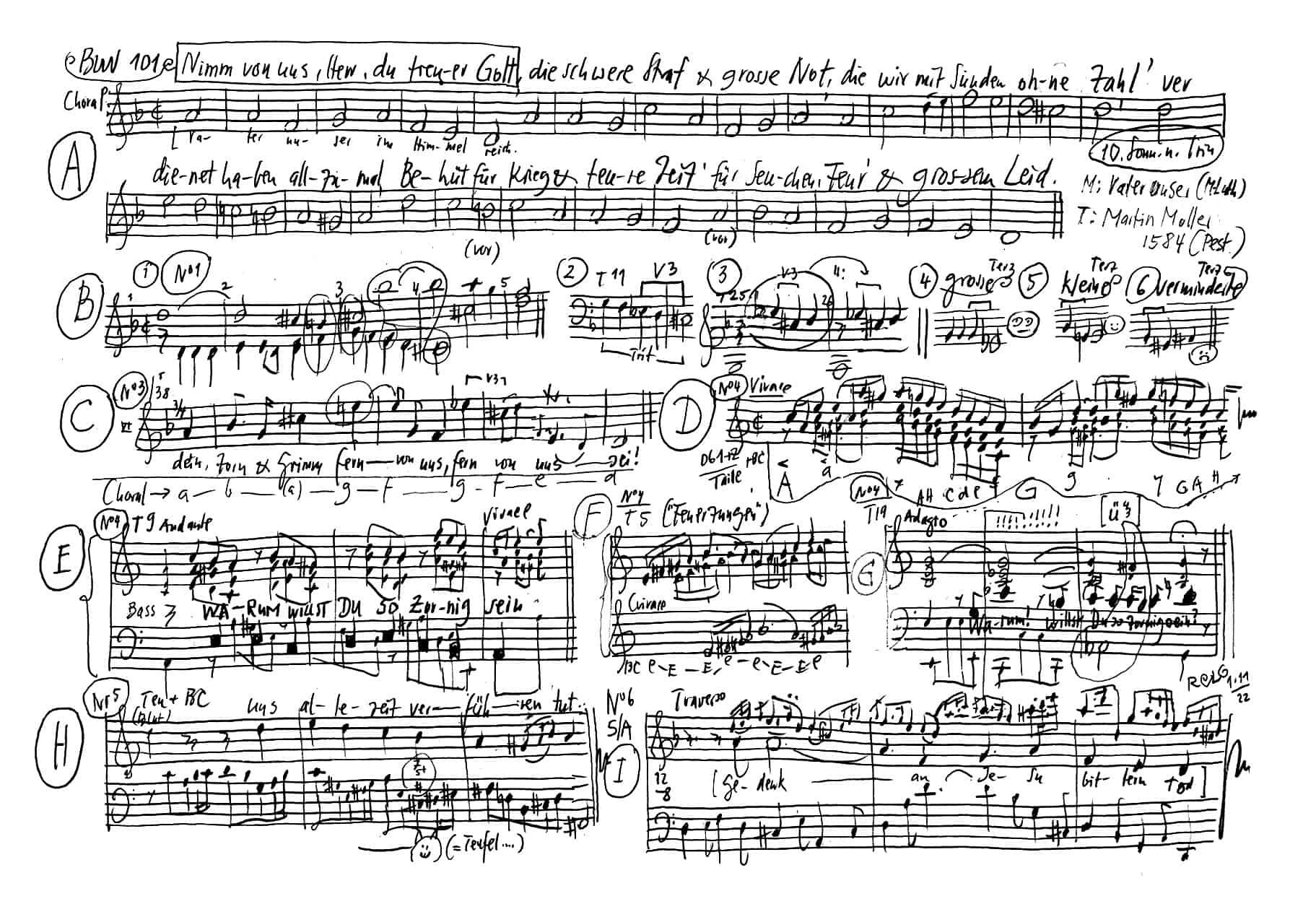

BWV 101 // For the Tenth Sunday after Trinity

(Take from us, Lord, thou faithful God) for soprano, alto, tenor and bass, vocal ensemble, cornett, trombone I–III, oboe I+II, oboe da caccia, strings and basso continuo

Would you like to enjoy our videos ad-free? Subscribe to YouTube Premium now...

Workshop

Reflective lecture

Choir

Soprano

Linda Loosli, Jennifer Ribeiro Rudin, Simone Schwark, Susanne Seitter, Noëmi Tran-Rediger, Mirjam Wernli

Alto

Laura Binggeli, Antonia Frey, Katharina Jud, Jan Thomer, Lisa Weiss

Tenor

Marcel Fässler, Tobias Mäthger, Joël Morand, Christian Rathgeber

Bass

Jean-Christophe Groffe, Israel Martins, Simón Millán, Felix Rathgeber, Philippe Rayot

Orchestra

Conductor & harpsichord

Rudolf Lutz

Violin

Eva Borhi, Cecilie Valter, Christine Baumann, Petra Melicharek, Ildikó Sajgó, Judith von der Goltz

Viola

Martina Bischof, Sonoko Asabuki, Sarah Mühlethaler

Violoncello

Maya Amrein, Bettina Messerschmidt

Violone

Markus Bernhard

Oboe/Oboe da caccia

Andreas Helm, Thomas Meraner

Taille

Ingo Müller

Cornett

Martin Bolterauer

Trombone

Christine Brand Häusler, Max Eisenhut, Tobias Hildebrandt

Transverse flute

Tomoko Mukoyama

Bassoon

Susann Landert

Organ

Nicola Cumer

Musical director & conductor

Rudolf Lutz

Workshop

Participants

Rudolf Lutz, Pfr. Niklaus Peter

Reflective lecture

Speaker

Rolf Stürner

Recording & editing

Recording date

18/11/2022

Recording location

Trogen AR (Schweiz) // protestant church

Sound engineer

Stefan Ritzenthaler

Producer

Meinrad Keel

Executive producer

Johannes Widmer

Production

GALLUS MEDIA AG, Schweiz

Producer

J.S. Bach-Stiftung, St. Gallen, Schweiz

Librettist

First performance

13 August 1724, Leipzig

Text

Martin Moller (movements 1, 3, 5, 7); unknown source (movements 2, 4, 6)

Libretto

1. Chor

Nimm von uns, Herr, du treuer Gott,

die schwere Straf und große Not,

die wir mit Sünden ohne Zahl

verdienet haben allzumal.

Behüt für Krieg und teurer Zeit,

für Seuchen, Feur und großem Leid!

2. Arie — Tenor

Handle nicht nach deinen Rechten

mit uns bösen Sündenknechten,

laß das Schwert der Feinde ruhn!

Höchster, höre unser Flehen,

daß wir nicht durch sündlich Tun

wie Jerusalem vergehen!

3. Choral und Rezitativ — Sopran

Ach! Herr Gott, durch die Treue dein

wird unser Land in Fried und Ruhe sein.

Wenn uns ein Unglückswetter droht,

so rufen wir,

barmherzger Gott, zu dir

in solcher Not:

Mit Trost und Rettung uns erschein!

Du kannst dem feindlichen Zerstören

durch deine Macht und Hülfe wehren.

Beweis an uns deine große Gnad,

und straf uns nicht auf frischer Tat,

wenn unsre Füsse wanken wollten,

und wir aus Schwachheit straucheln sollten.

Wohn uns mit deiner Güte bei

und gib, daß wir

nur nach dem Guten streben,

damit allhier

und auch in jenem Leben

dein Zorn und Grimm fern von uns sei!

4. Arie — Bass

Warum willst du so zornig sein?

Es schlagen deines Eifers Flammen

schon über unserm Haupt zusammen.

Ach, stelle doch die Strafen ein

und trag aus väterlicher Huld

mit unserm schwachen Fleisch Geduld!

5. Choral und Rezitativ — Tenor

Die Sünd hat uns verderbet sehr.

So müssen auch die Frömmsten sagen

und mit betränten Augen klagen:

Der Teufel plagt uns noch viel mehr.

Ja, dieser böse Geist,

der schon von Anbeginn ein Mörder heißt,

sucht uns um unser Heil zu bringen

und als ein Löwe zu verschlingen.

Die Welt, auch unser Fleisch und Blut

uns allezeit verführen tut.

Wir treffen hier auf dieser schmalen Bahn

sehr viele Hindernis im Guten an.

Solch Elend kennst du, Herr, allein:

Hilf, Helfer, hilf uns Schwachen,

du kannst uns stärker machen!

Ach, laß uns dir befohlen sein!

6. Arie — Duett: Sopran und Alt

Gedenk an Jesu bittern Tod!

Nimm, Vater, deines Sohnes Schmerzen

und seiner Wunden Pein zu Herzen!

Die sind ja für die ganze Welt

die Zahlung und das Lösegeld;

erzeig auch mir zu aller Zeit,

barmherzger Gott, Barmherzigkeit!

Ich seufze stets in meiner Not,

ich seufze stets:

Gedenk an Jesu bittern Tod!

7. Choral

Leit uns mit deiner rechten Hand

und segne unser Stadt und Land;

gib uns allzeit dein heilges Wort,

behüt fürs Teufels List und Mord;

verleih ein selges Stündelein,

auf daß wir ewig bei dir sein!

Professor Dr. Dres. h.c. Rolf Stürner

It is not easy to say something balanced about the text of J. S. Bach’s music when one is currently under the impression of the musical performance of Bach’s ingenious work, which may be counted among the particularly esteemed compositions in the series of well-preserved cantatas. For the text moves in images of a bus theology that needs an explanation for us today, which is already given, and at first glance it harmonises with our world view only to a very limited extent, just as its baroque pathos sometimes forces us into smiling distance. This does not mean that one should speak, for example, with Albert Schweitzer in his famous work on J. S. Bach, of a baseness above all of the recitative parts of the text, which, however, does not prevent Bach – according to Schweitzer admiringly – from integrating the text musically into his work of art with devotion and in a brilliant way. Nor should one join Thomas Mann in mocking the long tradition of bus texts with their figurative linguistic emotionality, as is done in “Buddenbrooks”, where Thomas Mann has the pietistic devotional congregation in the Buddenbrook house sing – in part quite plagiaristically, by the way – “Ach Herr, so nimm mich Hund beim Ohr,wirf mir den Gnadenknochen vor, und nimm mich Sündenlümmel in deinen Gnadenhimmel”. In the end, one could also brush aside the recitative text parts with the remark that in terms of quality and history of impact, they had an impressive commonality with other texts of great compositions in ecclesiastical and secular music, which not infrequently attracted literary ridicule, without this ultimately harming the reputation of the musical work of art. The following reflections aim to show that a self-confident setting aside of parts of the textual basis of Bach’s musical art does not do justice and that it is precisely the Gesamtkunstwerk that makes us intensely aware of a remarkable powerlessness, even of the present, in the face of destructive forces of human nature. There are certainly textual elements of the bus text that contain a message understandable to and worthy of approval by every musician and listener, while others presuppose an affirmative familiarity with doctrines or dogmas of Christian tradition and therefore often harmonise with the individual world view of musicians and listeners with difficulty or not at all, so that a performing identification, especially of singers and musicians, may be more of a concession to fill a certain role, the insight value of which for performers and listeners should not be underestimated either, however.

First of all, a few considerations should be devoted to the present sometimes difficult handling of the general world view of the bus text. The worldview of the Reformation period, with its image of a human being who strives and calls for redemption from creaturely parts of himself, is shaped by the permanent fall into sin, and turns with its longing to a world-guiding God who is encountered in the text as a classical father figure, strict, responsive and at the same time turned towards. However, the idea that a person who controls the cosmos could intervene in the random events of matter that has been set in motion, or that he or she has pre-programmed certain interventions down to the last detail, is somewhat distant from our scientifically influenced present. The dominant current world view, which is predominantly shaped by the natural sciences, analyses life and human life as a random product of chemical reaction of inanimate matter, which becomes inanimate matter again with death and may then at some point energetically transform itself as a sum of insignificant small parts in black matter into something new that is as yet incomprehensible. Certain modern forms of burial seem to take up this idea somewhat. The image of God as a person who governs the cosmos runs a greater risk than in earlier times of being sidelined without being understood and appearing to many to be dispensable as a counterpart.

However, the contradiction between a divine presence guiding everywhere and all the time and a personal and in a certain sense humanised conception of God has been conscious and familiar to the biblical texts from their beginnings, and seen in this light, this fundamental contradiction is not a particularly new insight into our modern world. From inanimate matter, however, a human being has developed who longs for the empathy of others and who, in the course of his history, does not seem satisfied with transient interpersonal affection, but seeks an understanding and guiding permanent counterpart who is able to give meaning to his life beyond death. The reference in the text of repentance to the sacrificial death of the risen Jesus as a seal of God’s turning to man despite his sinfulness, combined with an intensive final expectation of a post-mortal existence with and at God, is the core of traditional Christian religious conviction and ecclesiastical dogmatics, which the vast majority of people today are less and less able to comprehend and support as a realistic expectation in the sense of compatibility with cosmic laws known to them. As a component of a religious-historical turn away from the traditional Old Testament laws and rules towards an ethic of love for one’s neighbour, modern man will often no longer accept it as reality, but with sufficient religious education, he will not hate it either. People may have very different opinions about the details of church and theologically dogmatised religiosity, but the search for meaning and attention is a given in human nature and determines their feelings and actions in many ways. In the biblical imagery, we encounter it as a search for God and, beyond our cultural sphere, it is a fundamental topos in the history of humankind to which philosophy, poetry and literature worldwide have devoted themselves and continue to do so, in German, for example, Goethe in his world theatre “Faust” or, with an Old Testament orientation, Thomas Mann in his “Joseph” tetralogy – both works, however, that threaten to fall victim to deletions even at higher levels of education.

However, there are also parts of the cantata’s bus text that make it easier for us to identify with it rationally and emotionally. The immediate present in particular confronts humanity worldwide with tensions that threaten to erupt again in warlike actions long thought to have been banished from the coexistence of different social cultures. Pandemics that cannot be controlled, or can only be controlled with difficulty, and climatic changes that are at least significantly influenced by humanity, with resulting scenarios of a creeping but certain demise of our earthly world, are also beginning to sensitively shape and disturb the attitude to life of large parts of humanity – all in all, a situation somewhat similar to the post-Reformation period in Germany and Central Europe. Western civilisation in Europe and above all in North America reacts to warlike incursions of a world thought to have been overcome by the Enlightenment with the harsh economic sanctions against the aggressor and with arms aid against the belligerent aggressor. Our cantata text classifies this response, which could not save many young soldiers and many Ukrainian civilians from death or murder, and whose effects are as yet open in their final consequence, as a human entanglement in sinful activity, to which man seems inescapably enslaved because he sins against other human beings, regardless of whether he helps or allows. In the language of the law of war, one speaks of collateral damage as the consequence of choosing the lesser evil. That would be the many young people who were recruited against their convictions and forced to make the sacrifice of their lives. Especially against the background of Russian-German history with the death and murder of an estimated 25-30 million people attributable to the Soviet Union in the Second World War, Germany’s decision to become involved in warlike misery on former Soviet soil may at least have been worth considering, and people of the older generation may have regretted that this connection was only briefly explained in public at best and not considered more thoroughly. Perhaps the following generations in parliament would then at least have avoided the standing ovation for the decision on active indirect intervention in parliament and would have given more room to a sober realisation that one was forced to participate in the shedding of blood even of many innocent or seduced people. The telegram about my birth reached my father, who was briefly trained and drafted as a soldier at a more mature age, in 1943 in Stalino, today’s embattled Donetsk. Looking at this document again and again, I would never have thought that Germany would ever again participate, even indirectly, in military actions on the soil of the former Soviet Union through targeted arms deliveries and threats.

Remarkable for our present day is the renunciation of the cantata’s bus text of a request for divine help in defeating the enemy in favour of a more balanced request for strengthening in defending steadfastness and for peace, i.e. for no so-called “victorious peace”, as it was coined as a term by the German generals of the First World War. This is by no means self-evident, since Christians on both sides have prayed for victory over the enemy for centuries and even in the First and Second World Wars. A lasting strength of Christianity is the traditional distance of Jesus as the founder of a religion from warlike violence, which Mohammed, for example, as the founder of the Islamic religion, did not practise without restrictions. With its pleas for repentance from sinful entanglement, the text makes it easier for us to classify the participation of our civilisation in causing climatic changes, as it mainly affects the industrial nations despite a certain beneficial role of the other part of the earth’s population and forces them into the main co-responsibility. A petition transformed into our own time for protection from the consequences of the sin against creation, combined with the expression of regret and remorse, will also include the petition for the protection and preservation of posterity and for the success of countermeasures planned by humanity with consensus and vigour.

Whoever plays Bach’s cantata or listens to it can do so as a fully believing Christian, as a doubter or atheist with an unbroken empathy for the text’s content that transcends time and its compositional exaltation, if he or she transposes the expressed wishes into the present and supports or at least tolerates God’s personal presence as a biblical image. In this way, one can devote oneself musically and textually to Bach’s work and make music without feelings of doubt and allow oneself to be carried along by listening, while at the same time taking note of the baroque pathos with a tolerant inner smile. Let us therefore – I conclude – play and listen to the cantata together again with rational deliberation and well-considered emotional identification.

This text has been translated with DeepL (www.deepl.com).