Allein zu Dir, Herr Jesu Christ

BWV 033 // For the Thirteenth Sunday after Trinity

(Alone to thee, Lord Jesus Christ) for alto, tenor and bass, vocal ensemble, oboe I+II, bassoon, strings and continuo.

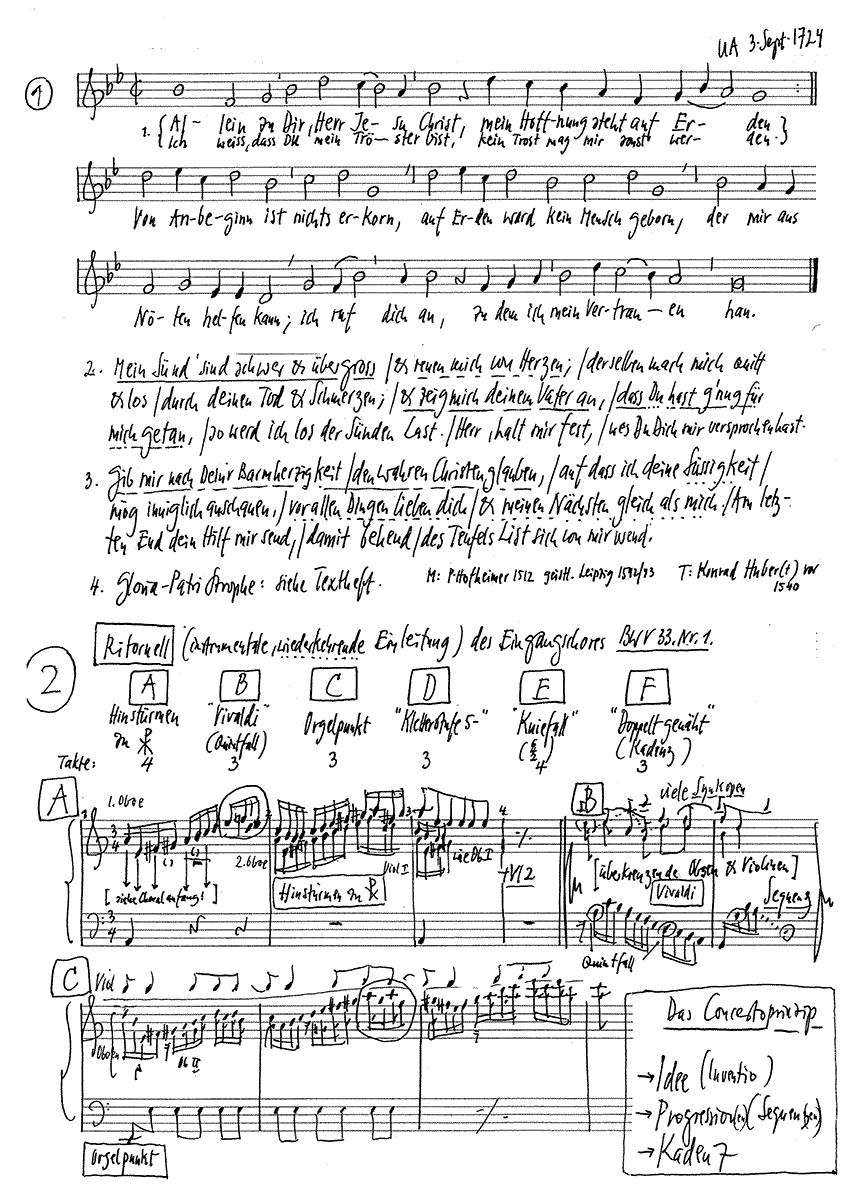

The chorale cantata “Allein zu dir, Herr Jesu Christ” (Alone to thee, Lord Jesus Christ), first performed on 3 September 1723, could – in analogy to a work by the Leipzig composer Johannes Weyrauch (1897–1977) – also be described as a “cantata of love”. Indeed, while it addresses justification by faith, the work’s musical and textual focus is primarily on the enlightening comparison of earthly and heavenly mercy and the exemplum of God’s burning love.

Would you like to enjoy our videos ad-free? Subscribe to YouTube Premium now...

Workshop

Reflective lecture

Choir

Soprano

Susanne Frei, Guro Hjemli, Jennifer Rudin

Alto

Jan Börner, Antonia Frey, Franzisca Näf

Tenor

Walter Siegel, Manuel Gerber, Nicolas Savoy

Bass

Fabrice Hayoz, Chasper Mani, William Wood

Orchestra

Conductor

Rudolf Lutz

Violin

John Holloway (special Guest), Renate Steinmann, Sabine Hochstrasser, Mario Huter, Martin Korrodi, Livia Wiersisch

Viola

Joanna Bilger, Martina Bischof

Violoncello

Maya Amrein

Violone

Iris Finkbeiner

Oboe

Luise Baumgartl, Martin Stadler

Bassoon

Susann Landert

Organ

Markus Maerkl

Musical director & conductor

Rudolf Lutz

Workshop

Participants

Karl Graf, Rudolf Lutz

Reflective lecture

Speaker

Susanne Sinclair

Recording & editing

Recording date

08/31/2007

Recording location

Trogen

Sound engineer

Stefan Ritzenthaler

Director

Meinrad Keel

Production manager

Johannes Widmer

Production

GALLUS MEDIA AG, Switzerland

Producer

J.S. Bach Foundation of St. Gallen, Switzerland

Librettist

Text No. 1, 6

Konrad Huber, 1540

Text No. 2–5

Poet unknown

Year of composition

1724

In-depth analysis

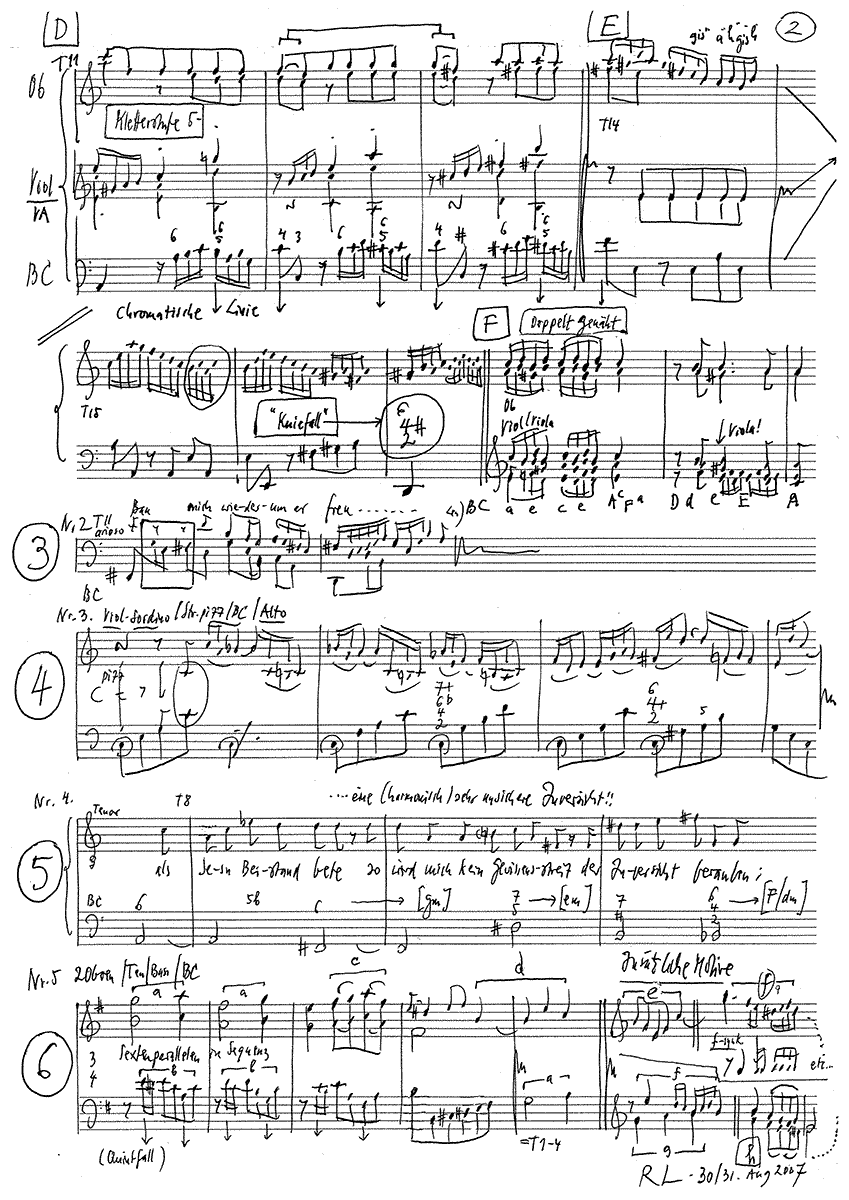

The introductory chorus, a boldly spirited A-minor concerto, is characteristic of the type that Bach composed with inexhaustible inventiveness throughout his chorale cantata cycle of 1724/25. The orchestra plays the dominant role in the movement’s structure, with block-style choir passages inserted into the instrumental material of strings and oboes. In a developmental-style section, these compact chorale lines enhance the sense of an excited acceleration of events, an impression already evident in the sequence of entries in the opening ritornello. Indeed, throughout the text of this early Protestant chorale, the irascible Thomas Cantor can almost literally be heard thundering down the stairs, gearing himself up for a further battle in his lifelong crusade for better working conditions – with little in the way of negotiating skills or supporters, and armed solely with the motto “Jesu juva” and his fierce artistic pride …

In contrast, the bass recitative expresses an open-hearted confession of sin and the humble awareness of one’s own fallibility. In recounting the lack of “love” and “strength of spirit” inherent to human beings, it becomes increasingly apparent that only Christ can warrant hope in the face of judgement, grant forgiveness, and bestow the “gladness” captured in the embellished arioso section.

The alto aria has a particularly distinctive style, characterised by pizzicato broken chords in the bass, a sparse layer of pizzicato strings, and the incessant sighing of the first violin (muted, in accordance with the marking of “col surdino” on the autograph score) to create a picture of despondency that equally expresses utter humility and pure, childlike trust. Where human power has been exhausted, the only hope remaining is that someone will carry the “weight of sin” (interpreted by Bach in a succession of sharp notes) – although this passage embodies comfort more as the remembrance of love than as keen relief. As the saints in late medieval altarpieces protectively present kneeling benefactors, Jesus must play the role of intercessor with the stern father. Here, the seemingly plain music reveals a topos of sorrow that materialises as a spiritual exercise of penitence. In particular, the word “depressed” is presented as a strong undertow, while the “fearful wavering” of steps is trapped in an indecisive circular movement. The length of the aria itself may also be interpreted as a reference to the duration of penance, which according to Luther’s first thesis on indulgence should span the entire lifetime of the faithful.

The following tenor recitative “My God, reject me not” relates a further aspect of penance with fervent contrition. In this imploring entreaty to withstand the test of God’s countenance, the Protestant doctrine of justification by faith is succinctly revealed: from the “faith both true and Christian” found in Jesus’ comfort, the good deeds of mercy must follow.

In keeping with Bach’s preferred type of cantata in Leipzig, a further aria, “God, thou who art love now called”, would be expected. But in fact, an instrumental prelude ensues, whose modular purposefulness and ostinato bass figure make it more akin to a ritornello of a figured closing chorale. The consonant duet passages for tenor and bass, resembling ornate hymn lines, also demonstrate a chorale-like character. Combined with the captivating timbre of love from the oboe, an insistent yet appealing song emerges that fluctuates between the humble search for fellowship and the desire for spiritual rapture.

After this bold, personal appeal to God, the closing verse of Konrad Hubert’s hymn, a doxological chorale to the praise of the Holy Trinity, offers a profound and equally objectified conclusion to a cantata that presents an individual’s chosen way of life, theology, doctrine and, finally, the church as the fruit of hopeful love found in true faith.

Libretto

1. Chor

Allein zu dir, Herr Jesu Christ,

mein Hoffnung steht auf Erden;

ich weiß, daß du mein Tröster bist,

kein Trost mag mir sonst werden.

Von Anbeginn ist nichts erkorn,

auf Erden war kein Mensch geborn,

der mir aus Nöten helfen kann.

Ich ruf dich an,

zu dem ich mein Vertrauen hab.

2. Rezitativ (Bass)

Mein Gott und Richter, willt du mich

aus dem Gesetze fragen,

so kann ich nicht,

weil mein Gewissen widerspricht,

auf tausend eines sagen.

An Seelenkräften arm und an der Liebe bloß,

und meine Sünd ist schwer und übergroß;

doch weil sie mich von Herzen reuen,

wirst du, mein Gott und Hort,

durch ein Vergebungswort

mich wiederum erfreuen.

3. Arie (Alt)

Wie furchtsam wankten meine Schritte,

doch Jesus hört auf meine Bitte

und zeigt mich seinem Vater an.

Mich drückten Sündenlasten nieder,

doch hilft mir Jesu Trostwort wieder,

daß er für mich genung getan.

4. Rezitativ (Tenor)

Mein Gott, verwirf mich nicht,

wiewohl ich dein Gebot noch täglich übertrete,

von deinem Angesicht!

Das kleinste ist mir schon zu halten viel zu schwer;

doch, wenn ich um nichts mehr

als Jesu Beistand bete,

so wird mich kein Gewissensstreit

der Zuversicht berauben;

gib mir nur aus Barmherzigkeit

den wahren Christenglauben!

So stellt er sich mit guten Früchten ein

und wird durch Liebe tätig sein.

5. Arie (Duett Tenor, Bass)

Gott, der du die Liebe heißt,

ach, entzünde meinen Geist,

laß zu dir vor allen Dingen

meine Liebe kräftig dringen!

Gib, daß ich aus reinem Triebe

als mich selbst den Nächsten liebe;

stören Feinde meine Ruh,

sende du mir Hülfe zu!

6. Choral

Ehr sei Gott in dem höchsten Thron,

dem Vater aller Güte,

und Jesu Christ, sein’m liebsten Sohn,

der uns allzeit behüte,

und Gott dem Heiligen Geiste,

der uns sein Hülf allzeit leiste,

damit wir ihm gefällig sein,

hier in dieser Zeit

und folgends in der Ewigkeit.

Susanne Sinclair

“Surely the Ten Commandments should be enough”.

Thoughts on the inflation of the ethical

Even a first skim of the cantata text immediately reveals what distinguishes the first and sixth stanzas from the second and fifth. The first and sixth stanzas could be described as a confession of faith, a kind of starting point and conclusion at the same time. The second and fifth stanzas, on the other hand, speak of a peculiar mixture of acknowledgement of guilt, despair and description of fears and hopes. In essence, however, both parts of the text are about how man can attain eternal life and about the eternal question of whether this should be done through direct faith in God the Father or through faith in Jesus as mediator.

I therefore asked myself who in our society still describes acknowledgement of guilt, despair and fears and hopes and how this actually happens. It is striking that there is hardly any talk about Christianity and faith any more, not even about sin and forgiveness. But does that mean that Christianity, faith, sin and forgiveness are no longer relevant to us?

No. At least not in economics and politics. There, people have been talking about ethics and the complications and problems associated with it for some years now. As soon as an ethical problem is recognised, new guidelines, laws and contracts follow that are supposed to bring a solution. On closer examination, this has always corresponded to human nature. For man wants to follow rules, he wants to control the emotional side effects, and he wants to win over an opponent. The rules for this are the basis of every game and are therefore already known to every child. Breaking the law has also been done in a playful manner since time immemorial.

What has changed over the centuries are the interpretations of rules. In addition, we must recognise today that opponents often become irreconcilable enemies and that fair play or action are therefore no longer possible.

In the cantata it says: “My God and judge, if you want to ask me / from the law, / I cannot, because my conscience contradicts.” Today, rules and laws range from the Wolfsberg Principles to the United Nations Conventions to the Sarbanes-Oxley Act. Indeed, people try to answer ethics questions with “principles”, conventions and acts. But isn’t it a contradiction that we invent a business ethic, a political ethic, an ethic for business, an ethic for the environment and an ethic for the home? Who is actually responsible for which ethics? And what does responsibility look like? Can I accept one ethic and neglect the other? How can that be done? And last but not least: What are the consequences if I act unethically? “ALONE TO YOU, Lord Jesus Christ?” The title of the cantata, or more precisely, the exclusivity of Christ, deserves a question mark today. Indeed, what is the need for formulated corporate governance rules if the 10 Commandments exist and everyone in our culture would abide by them? Probably, the formulation of basic religious values over time has led to them being misused as an alibi. The anchoring in the written word by human hands has unfortunately had the consequence that people have used and misused the word as their law. This began with the first biblical writings. Comfort, mercy, love, forgiveness do not need the written word to work. The word was originally only meant to illustrate these virtues.

Corporate culture also only comes alive when it is lived by everyone and from within. But this seems to be the problem of our time. We only believe what we can read. What is written seems like proof or fact. And yet, or precisely because of this: what is written and regulated can be interpreted and transgressed more easily. That has always been the case, but in earlier times the written word was rarer and more valuable. A cantata text is therefore not a written text, but the record of a personal request, an appeal to the one who grants eternal life.

In a society of unbroken information overload, respect for rules and guidelines has become diluted. They have become depersonalised and factual. And with objectification comes a certain distance. Basically, exactly the opposite of what is supposed to be achieved with the inflation of new rules. But ethics is not the same as morality, and morality is not the same as faith. Because a little tax evasion or insurance fraud, cheating or just a little wheeling and dealing – all that has become socially acceptable, because everyone goes along with it. Who needs forgiveness from a God today?

The following verses of the cantata make the difference to our time obvious:

“Poor in strength of soul and bare in love,

and my sins are grievous and exceeding great;

But because they repent me with all my heart,

“Thou, my God and my refuge,

“will make me glad again with a word of pardon.”

“How fearfully my steps have wavered,

but Jesus listens to my plea

(…).”

“I was weighed down by the burden of sins,

but Jesus’ word of comfort helps me again,

(…).”

“My God does not reject me,

“though I transgress thy commandments daily.

(…).”

If the request for forgiveness still gave hope to Bach’s contemporary, we ourselves determine who the Father in heaven, the Son of God, the commandments are, but also who and what constitutes love, mercy, consolation, right and wrong. Awareness of injustice today is something that is determined by man and can be freely interpreted, and forgiveness often turns into tolerance even for the intolerable. With a few exceptions, religiosity has become an individual thing in Western society. It is nobody’s business. And if it is, we simply give the religious a different name. Thus, in the cantata we read:

“God, whose name is love,

oh set my spirit on fire,

Let to thee above all things

let my love penetrate to thee.”

But for the new rules of corporate behaviour we have found the term corporate governance, and chat groups are the places where young people dream of love and mercy.

Those who do good talk about it above all. Philanthropy is organised. Sometimes, it is true, one has the feeling that what one hand takes, the other wants to give back. But that is quite all right. After all, the danger does not come from the philanthropists who like to give. They are actually committed to a good cause. The danger lies in the fact that in this way the great masses shirk their personal responsibility. They make God and being good a matter for the bosses. According to the motto “they can afford it”, both respect and doing good are put on a big track. The neighbour’s little cries for help may go unheard. But charity was not meant that way. The stories and parables of the Bible took no account of status and wealth.

The attainment of eternal life was originally given by helping the neighbour unselfishly and discreetly, according to the model of Jesus, but for the love of the Father. I do not believe that people in the Western world today have lost their faith and their ability to practise charity. But perhaps they no longer have the courage to actively profess it in their daily lives. They no longer say’ I believe in God and in his only begotten Son, but rather, “I believe in something, it’s not clear, later there is something.” Precisely, I believe that in a society that controls and masters everything, man has not become fearless, but perhaps more godless. In the hectic pace of everyday life, we are in “command” and to the extent that the idea of eternity no longer determines our actions, many questions have become irrelevant.

Some already see in the climate challenges of our planet a tsunami of faith – a kind of ultimate punishment for the sins of humanity, for industrialisation and capitalism. Or else a turning away from God and proof of godlessness. These thoughts are not new. In everyday life, consolation is often sought in compensation rather than through prayer. God, as he presents himself to us, is no longer a helpline of life.

And yet, when disaster strikes, people mobilise immediately and strongly. We can obviously still be touched! And God is immediately there again, as are the nudging prayers and perhaps much more.

Let’s look at it positively: The striving for corporate governance and for the various forms of ethics of modern life, for more and more written standards is, in my view, a modern kind of helplessness, probably also a cry for help! We have changed the language and the structures, but the needs remain the same.

“Glory to God in the highest throne,

the Father of all goodness,

and Jesus Christ, his dearest son.

who keeps us always”,

teaches the cantata. Indeed, we are neither godless nor lost. Rather, I believe that we must learn again to put more trust not in rules set by us, but in inviolable virtues. Love, mercy, loyalty, faith, respect, solidarity, trust, confidence and strength come from within ourselves, whatever religion one chooses. In fact, the written word must only be a tool, not a means to an end.

And then there is music! It remains unchanged for centuries. It invites and connects. It does not necessarily need words to do justice to its spirituality. So everyone, quietly, can have their own thoughts played, not without relevance, by the way, thanks to Johann Sebastian Bach.

We need cantatas, and we need a little more courage

“here in this time and hereafter in eternity”.

This text has been translated with DeepL (www.deepl.com).