Messe A-Dur

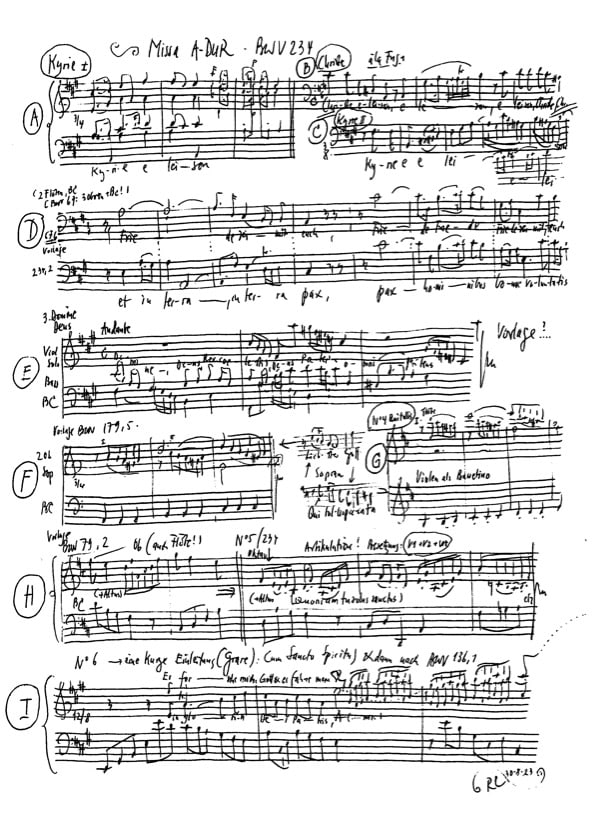

BWV 234 //

(Mass in A Major) for soprano, alto and bass, vocal ensemble, transverse flute I+II, strings and basso continuo

Would you like to enjoy our videos ad-free? Subscribe to YouTube Premium now...

Workshop

Reflective lecture

Choir

Soprano

Simone Schwark, Mirjam Wernli, Lia Andres, Cornelia Fahrion, Susanne Seitter, Jessica Jans

Alto

Tobias Knaus, Antonia Frey, Lisa Weiss, Lea Scherer, Francisca Näf

Tenor

Sören Richter, Christian Rathgeber, Klemens Mölkner, Zacharie Fogal

Bass

Philippe Rayot, Christian Kotsis, Israel Martins, Tobias Wicky, Jonathan Sells

Orchestra

Conductor

Rudolf Lutz

Violin

Éva Borhi, Lenka Torgersen, Christine Baumann, Petra Melicharek, Ildikó Sajgó, Judith von der Goltz, Aliza Vicente

Viola

Sonoko Asabuki, Lucile Chionchini, Matthias Jäggi

Violoncello

Maya Amrein, Daniel Rosin

Violone

Markus Bernhard

Transverse flute

Tomoko Mukoyama, Rebekka Brunner

Bassoon

Susann Landert

Harpsichord

Thomas Leininger

Organ

Nicola Cumer

Musical director & conductor

Rudolf Lutz

Workshop

Participants

Rudolf Lutz, Pfr. Niklaus Peter

Reflective lecture

Speaker

Dorothea Lüddeckens

Recording & editing

Recording date

15/09/2023

Recording location

St. Gallen (Switzerland) // Cathedral

Sound engineer

Stefan Ritzenthaler

Producer

Meinrad Keel

Executive producer

Johannes Widmer

Production

GALLUS MEDIA AG, Schweiz

Producer

J.S. Bach-Stiftung, St. Gallen, Schweiz

Librettist

First performance

1738/1739 – Leipzig

Libretto

Kyrie

1. Chor

Kyrie eleison,

Christe eleison,

Kyrie eleison.

Gloria

2. Chor

Gloria in excelsis Deo,

et in terra pax hominibus bonae voluntatis.

Laudamus te, benedicimus te,

adoramus te, glorificamus te.

Gratias agimus tibi propter magnam gloriam tuam.

3. Arie — Bass

Domine Deus, Rex coelestis,

Deus Pater omnipotens,

Domine Fili unigenite Jesu Christe,

Domine Deus, Agnus Dei, Filius Patris.

4. Arie — Sopran

Qui tollis peccata mundi,

miserere nobis,

suscipe deprecationem nostram.

Qui sedes ad dexteram patris,

miserere nobis.

5. Arie — Alt

Quoniam tu solus sanctus,

tu solus Dominus,

tu solus altissimus Jesu Christe.

6. Chor

Cum Sancto Spiritu

in gloria Dei Patris, amen.

Dorothea Lüddeckens

Music and religion – integration and rejection

Music, religion and rituals are closely linked throughout the millennia of religious history and across cultures. In Islamic mysticism, for example, we find music as an elementary component of the deepest meditation and ecstasy practices; the scholar Al-Ghazali already reflected on this theoretically in the 11th century. There is Muslim rap and Friday prayers include the recitation of the Koran, which is not considered music from an Islamic theological perspective, but is at least a chant.

The second book of the Torah describes the successful escape of the Israelites from Egypt and, on reaching the shore of salvation, it is reported: “Then Miriam the prophetess, Aaron’s sister, took a timbrel in her hand, and all the women followed her with timbrels in a round dance” (Exodus 15:20). The pianist and musicologist Jascha Nemtsov sees this as the beginning of Jewish music. To this day, music plays a decisive role in Orthodox services in particular, so the biblical texts are not read aloud, but sung with melismas and cadences

The musical recitation of religious texts is also central to Buddhism and the recitation of the sutras, i.e. the canonical discourses, is also accompanied by rhythm instruments in Japan, for example.

Without the need and encouragement to express the Christian faith musically, many things would not have come about. There would be no Missa A, no blues and no jazz, no Elvis, no Johnny Cash and no Aretha Franklin.

Music is deliberately used in religions or is regarded as highly dangerous and forbidden.

When the Taliban came to power in Afghanistan, religious arguments were used to ban all music – apart from the recitation of the Koran.

In ultra-orthodox Jewish circles, non-Jewish music is generally forbidden.

Theravada Buddhist nuns and monks are not only forbidden to make music themselves, but also to listen to music.

And I can well remember how colleagues from my youth group destroyed their records when they converted to Christianity.

And to this day, Pope John XXII is known for banning the “Ars nova” with its polyphonic vocal music in 1324/25. He threatened to punish the church and accused this music of “beguiling the ears without caring for the soul” and that instead of being given by God, these sounds were merely invented by their composers. Bach was also familiar with this kind of criticism of his music.

The potential of music

Music is, quite obviously, extremely powerful, otherwise it wouldn’t have to be banned.

As we know today, their effect is also due to our basic biological make-up. Acoustic signal processing, and therefore also music, is processed directly in the brain stem and the limbic system even before the signals reach the auditory centre and therefore our consciousness. This means that sounds influence our basic regulatory processes such as breathing, our heartbeat, even our body temperature and, above all, our emotions.

Sounds therefore directly influence our emotional and cognitive states of consciousness.

Jörg Frey already said it yesterday: music can put us in ecstasy – according to my colleague, it takes us “out of ourselves and into somewhere else”, and then he said: “Completely with God and precisely in that completely with us.”

This “completely with God” is the language of the theologian and believing Christian.

As a social and religious scientist, I would put it a little differently:

Music enables the experience of being completely absorbed in something. It enables a concentrated focus in which everything outside of this musical experience is no longer perceived. The sounds and rhythms fill us, and it is possible for the message of a sung text to completely occupy our inner perceptual space.

As thinking, reflective people, we dissolve to a certain extent in this experience, but at the same time it is precisely this feeling: being completely with ourselves.

This experience is also possible collectively, for example during national anthems or football chants.

All musical listening is also culturally influenced. So I assume that very few of you get into a euphoric mood when you hear the fan chants of FC St. Gallen.

I also assume that Bach’s music does not trigger the same emotions in all of us in this cathedral, but certainly intense and positive ones.

Successful rituals

In rituals, music is used to reinforce or bring about exactly what makes a successful ritual:

In its most intense moments, it not only simply casts a spell over us, but we become one with the ritual, with its movements, its dynamics.

The difference between us and the ritual event dissolves, in extreme cases it can lead to trance or even ecstatic experiences.

Successful ritual practice is a form of concentration that does not have to ask what comes next at every moment. Rather, it is a concentrated presence in which you can surrender to what is happening.

Good music and good rituals require intellect. At the same time, however, the experience of musical events and ritual practice goes beyond the mind; music and ritual are about physical experience, emotions and aesthetics.

Music and rituals share essential elements. Both recognise repetition and repeatability. And in both cases, there is a quality in this that enables a deepening. In his reflection last year, Beat Grögli spoke of the joy of repetition, “repetitio iuvat”.

Even in the case of the music we hear today, music and ritual originally belonged together. After all, Bach composed the Mass Breves for the Lutheran church service, i.e. for a religious context, a religious ritual.

Now we may be here in a cathedral, but we are not listening to this music tonight as part of a church service. And I assume that not all of you will personally agree with the semantic meaning of the sung texts:

– Kyrie eleison – Lord, have mercy –

There are probably some among us who will not inwardly respond to this request in the sense of a need for the mercy of a God in whom they do not believe.

And even among those of you who see yourselves as Christians, there are many for whom the concept of sin – and the fourth aria explicitly refers to the sins of the world – has become alien to them.

Many people in Western Europe today no longer share the conviction that Jesus died as a sacrificial lamb on the cross for the sins of mankind and in this way took their sins upon himself.

The experience of this music can nevertheless also be experienced by non-religious people as a religious or, perhaps you would rather say, spiritual experience.

So-called sacred music is even attracting more people today in some cases, even if the faith associated with the composition of this music is declining.

Apart from musical appreciation, this also has to do with the fact that in our society the need for experiences that remove boundaries, for being uplifted and emotionally challenged in a positive sense is less satisfied in traditional religious forms than, for example, in the experience of concerts.

The Russian pianist Arcadi Volodos expressed this last year when he said in an interview: “I’m not an expert on religion. Just this: I think you can find more spirituality in music than in the church.” [1]

I think something else plays a role with regard to spiritual music. Anyone who has a personal relationship with this God, with this Christ, of whom this music sings, can in a sense sing along with his faith here.

However, this is no longer the case for many concert-goers today. Nevertheless, this sacred music seems to have a very special appeal.

Many experience the lack of the certainty of a Christian belief in God, of being lifted up in a ground of meaning that is woven into everyday life, with clear patterns of interpretation; they experience this lack as a loss, a loss that cannot be reversed, and perhaps they don’t even want to.

Immersing oneself in music that is connected to this faith, however, makes it possible to establish a connection to it without having to adopt the specific patterns of interpretation.

The pleading and urging of the first chorus in today’s mass, the jubilation of the Gloria in excelsis Deo, the dramatic experience of burden and redemption, the restlessness of the third aria and again the final jubilation in the last chorus – all this can also find its counterpart in a spirituality that is alien to Christian interpretation.

They are transcendent horizons of experience that can be connected with different ideas, with a Christian God or with the interpretations of a spirituality of nature or even with psychological concepts.

Bach’s masses touch many people both within and outside his Christian cultural context, regardless of whether they personally share or even understand the content of the texts set to music.

My wish for all of us this evening is that we can now surrender ourselves completely to this music and what it triggers in us, and at the same time experience being completely with ourselves and – if it is right for you – completely with God.

[1] Interview in “Spiegel” 19/2017, online from 5 May 2017.

This text has been translated with DeepL (www.deepl.com).